Gestalt meets cognitive behavioural coaching

Wright, N. (2012) ‘Gestalt Meets Cognitive Behavioural Coaching’, Training Journal, Fenman, January, pp64-69.

Introduction

Recently, I was invited to do some research into contemporary coaching thinking and practice, comparing and contrasting two different approaches in this field. As I glanced across the landscape of psychological schools, two stood out to me in particular: gestalt and cognitive behavioural (CB). I will introduce these approaches in this article, describe their distinctive characteristics, provide examples of what they could look like in practice and offer a critique.

Orientation

A gestalt practitioner is likely to approach a client with the unspoken question, ‘what is the unmet need?’ and a CB counterpart the same client with a different question, ‘what is the defective thought?’ Both reflect an implicit or explicit problem-solving orientation, although their hypotheses and approaches to enabling the client solve the perceived problem could be quite different in practice.

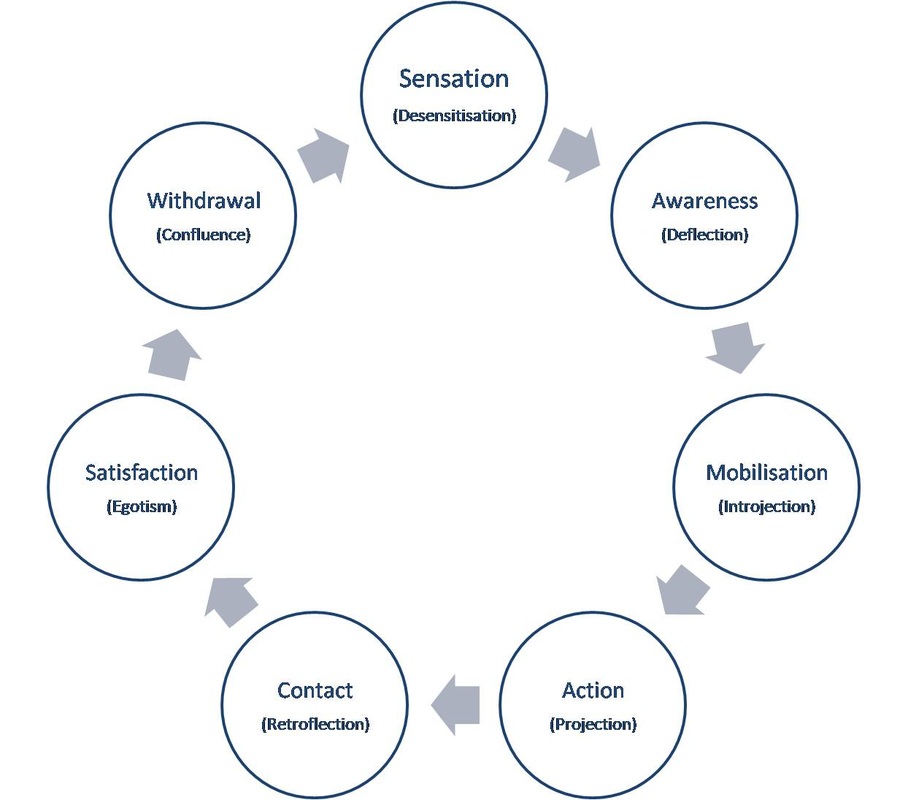

In gestalt coaching, a central concept is the cycle of experience (fig 1), based on physiological experiences of and strategies for need fulfilment and extrapolated to wider dimensions of human experience. This model is used in coaching to identify and address needs in individuals, dyads, teams, organisations etc, e.g. a need to conclude or reach resolution of unfinished business.

Figure 1: Gestalt Cycle of Experience

(corresponding blocks to awareness in brackets)

Typical questions include: ‘Where is the client/client system stuck as he/she/it seeks to move forward? or, ‘What is the most pressing need in this situation?’ An example could be an individual client who had an argument with her colleague that was never fully resolved. The client avoids situations at work with potential for conflict in order to avoid a similar experience.

A gestalt coach may invite her to focus on how she feels now, living with unresolved conflict, or what she would like to say to the colleague if he or she were present. The coach may then invite the client to resolve the conflict in the present by speaking to the other party as if he or she was physically in the room and, thereby, enable to client psychologically to move forward.

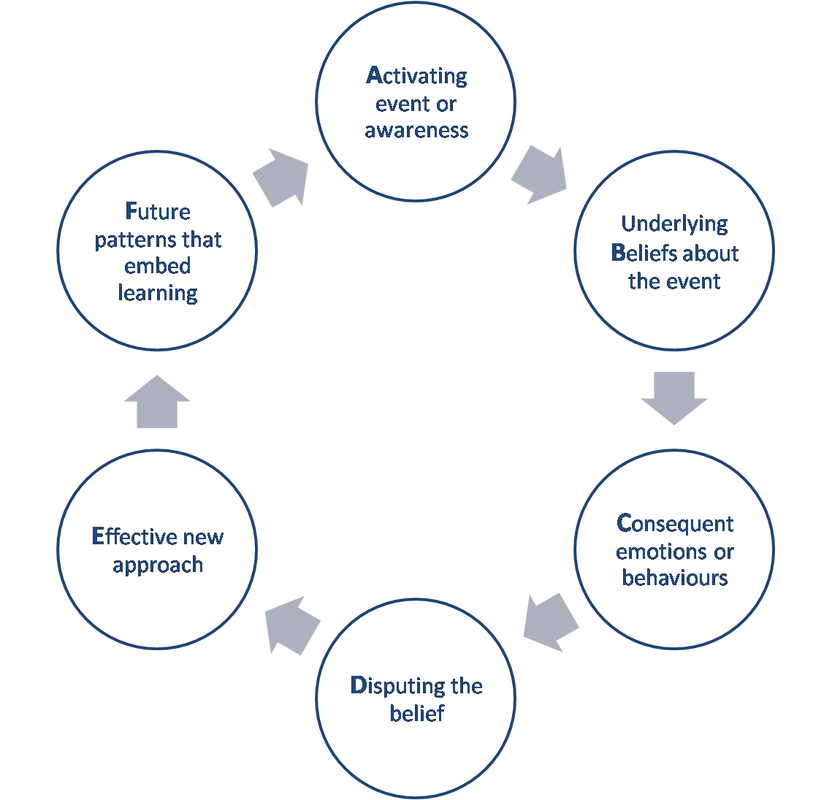

In CB coaching, a correspondingly common model is the ABCDEF framework (fig 2), sometimes preceded by ‘G’ which indicates a client’s implicit or explicit goal. The process starts by exploring conscious or subconscious beliefs that influence a client’s feelings about or behavioural responses to an experience, or his or her attitude towards a future course of action.

This initial stage is followed by enabling the client to challenge his or her own beliefs and replace unhelpful beliefs and behaviours with constructive alternatives that enable goal fulfilment.

Figure 2: ABCDEF Framework

The CB coach may work with the same client introduced in the gestalt example above by helping her surface what conclusions she has drawn from this experience (e.g. ‘If I get into conflict, I won’t be able to deal with it, therefore it’s best to stay away from situations that could lead to conflict’) and how these beliefs are influencing her behaviour (e.g. in this case, ‘avoid situations with potential for conflict’).

The coach may then challenge her to explore the validity of these beliefs (e.g. ‘are there situations in which you have successfully resolved or coped with conflict?’) and encourage her to experiment with new behaviours that lead to more constructive ways of dealing with relationships in the future.

These examples illustrate how gestalt and CB pay attention to how the client is experiencing a situation or relationship in the here-and-now. In practice, both these schools tend to be interested in the past or future only insofar as they exert influence in the present.

Experience

Gestalt practitioners refer to the client environment as the field. The field is the total context of a person’s internal and external experience, which includes the presence and influence of the coach in that person’s experience. Helping the client explore his or her field focuses on raising the client’s awareness of how he or she experiences and configures that environment subjectively based on his or her beliefs, thoughts, interpretations, feelings etc, e.g. ‘What am I experiencing?’, ‘What sense am I making of my experience?’ and ‘How is my experience influencing me in the present?’

The notion of field in gestalt relates to another central concept, figure and ground, where figure is that which emerges at any one time for a person or group and captures the attention vs ground as the backdrop to the figure that tends to go unnoticed. A gestalt coach may both help raise the client’s awareness of what is figural in the moment (e.g. the presenting issue or story) and explore the ground (e.g. how the client is feeling as he or she relates the story, what other ‘stories’ he or she is part of) as a means to evoking fresh awareness and insight.

When exploring the ground, the coach may pose questions that feel paradoxical, e.g. ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What isn’t featuring in the story?’, ‘What are we not talking about?’ or invite the client experimentally to physically demonstrate or role play aspects of his or her experience to see and feel what emerges. The coach may also offer observations (‘I notice...’) or self reflections (‘As you said that, I felt X’), using him or herself as part of the client field to raise the client’s awareness and insight.

This requires of the coach a high level of self-awareness, commitment to the client relationship and interpersonal skill to enhance the client’s awareness and development and avoid introducing unhelpful interference in the coaching process.

Another common gestalt method involves inviting the client to engage in experiments that exaggerate the client’s feelings. For example, if the client displays physical postures or movements whilst talking about his or her goals, thoughts or feelings, the coach may reflect this observation back to the client and invite him or her to exaggerate that posture or movement, thereby amplifying its effects, and see what fresh insight emerges.

A corresponding CB coach may typically enable a client to explore his or her experience using a conceptual model, e.g. SPACE framework, where S denotes Social context, how the client is performing within his or her context; P denotes Physical, what the client is experiencing physiologically; A denotes Action, how the client is behaving in his or her context; C denotes Cognitions, what perceptions and beliefs he or she holds in that environment; E denotes Emotions, how he or she is feeling.

The intention is to raise the client’s awareness of what he or she is experiencing in each dimension and how the client’s cognitions and behaviours are impacting on what he or she is experiencing. In this sense, the client is viewed systemically (cf gestalt field above); he or she is not only subject to the influences of his or her environment but also shapes that environment by how he or she perceives, behaves and acts within it.

As the client relates the situation or experience, the CB coach may offer observations or questions aimed at helping surface or crystallise the client’s underlying beliefs of assumptions. Again, as in gestalt coaching, this requires a high level of sensitivity and trust in the coach-client relationship. The coach may then present further questions aimed at challenging the validity of the client’s beliefs; not in terms of whether they are essentially ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ but in terms of how far they are supported by evidence, the ‘facts’.

The goal behind each question is to enable the client to gain a truer perspective, where ‘true’ = greater correlation with reality. I will comment on a social constructionist challenge to notions of objective reality under ‘critique’ below.

On one occasion, I approached a CB coach because I was experiencing unresolved conflict with a colleague, felt frustrated at my inability to resolve matters and, over time, tended to avoid her. After describing the relationship and how I was feeling within it, the coach posed a number of questions, common to CB coaching practice, aimed at challenging my evaluations and attributions in this relationship:

*Over-generalisation: e.g. was I generalising every interaction I had with the colleague as characterised by conflict, and ignoring exceptions’ (cf ‘what am I not noticing?’ in gestalt)?

*Fortune-telling: was I assuming that it would all go horribly wrong every time we meet, as if I could predict the future?

*Personalisation: was I taking sole responsibility for difficulties in the relationship rather than recognising my colleague’s contribution too?

*Catastrophising: e.g. did I typically anticipate worst case scenarios as I approached this colleague, rather than allowing for other possibilities to emerge?

*Mind-reading: e.g. was I making assumptions about her thinking based on my own interpretations of her behaviour?

Having explored my beliefs and thinking patterns, the CB coach encouraged me to test my own assumptions by engaging in cognitive and behavioural experiments, e.g. by meeting with the colleague and making a conscious note each time she behaved differently to how I expected; noticing how she behaved with other people and how they responded; smiling as I approached her, vividly imagining a positive experience, taking note of the result; asking her directly what she was thinking rather than assuming I already knew.

The goal of this kind of experimentation is to establish and reinforce new beliefs, thought patterns and behaviour that are more reality-based and, therefore, less dysfunctional and more constructive for the client, opening up fresh possibilities for the future. It entails developing the client’s own thinking skills, enabling him or her to identify limiting thoughts in the future and take intentional steps to address them.

In this example, I was able to develop a new sense of perspective on myself, my colleague and the relationship between us. Although it continued to be a difficult relationship, I felt more free within it, more able to be myself, more able to recognise when things went well, more able to differentiate my own contribution from hers in what happened between us. As a result, I felt less nervous about meeting with her, less inclined to avoid her, more able to reach out towards her in constructive ‘adult-adult’ mode.

As illustrated by these examples, gestalt and CB both seek to harness the power of imagination, gestalt by experimenting and possibly enacting (e.g. via drama or role play) and CB by visualising or vividly imagining new scenarios. In gestalt, the power of insight and change often comes from physically doing something within the coaching encounter itself, in CB by mentally ‘doing’ it or going away and practising a new behaviour or approach.

Holism

Gestalt may be regarded as distinctive and unusual in Western culture by its characteristic attention to the body. At one end of the spectrum, some gestalt practitioners regard the mind as an interference to insight and awareness because it can be so misleading and self-deceiving. Others regard the body and psyche as identical.

In gestalt, the body is regarded as a means by which need may be expressed genuinely and without conscious realisation, unfiltered by what Freud refers to as the superego. I have a personal coaching example:

I was working with a gestalt coach, as client, and commented that I felt anxious about approaching a forthcoming presentation to an executive team. Rather than suggesting we discuss this, the coach invited me to stand, role play walking into the executive team meeting and show him what feeling anxious might look like. As I enacted this scenario, he commented that I was holding my right hand across my chest, as if covering my heart. I had no awareness of this until he mentioned it.

We then explored what ‘covering my heart’ might mean symbolically. I became aware that I characteristically presented to this particular team in highly detached, rational-analytical mode and never really expressed my heart, how passionate I felt about what I was presenting on, how much it mattered to me personally. The coach suggested role play the scenario with my right hand in a more open position, thereby ‘revealing my heart’, and to rehearse speaking to the hearts rather than the minds of the executive team.

The subsequent meeting with the executive team was very different to anything I had experienced previously. It felt more human than technical, I received strong support for my proposal and felt supported personally too. The team was highly engaged and I left feeling confident and encouraged. The experience demonstrated powerfully to me that the body itself can convey valuable subconscious messages that lie outside of conscious awareness and that paying attention to the body can yield profound results.

CB too pays attention to the client’s physical experience (see SPACE model above), albeit primarily as a data source for what the client may be thinking and feeling or to see how it could be impacting on the client’s mental an emotional state. I believe recent research into rationality and intuition could help build a bridge between cognitive, emotional and physiological dimensions of experience, e.g. explaining how intuitive insight is often experienced somatically and expressed using physical-metaphorical language, e.g. ‘hunch’, ‘gut feeling’.

Critique

Bias

The CB coach is more likely than his or her gestalt counterpart to offer a theoretical framework along with a tentative ‘diagnosis’, implying an interpretation, of the client condition along with a proposed action plan; thereby acting as expert or personal development mentor. he risk is that the CB coach could superimpose his or her own values or frame of reference on the client in such a way that feels unethical or unfitting, particularly in cross-cultural environments.

The gestalt coach is more likely to offer observations, ‘I notice...’ without interpretation, aiming to raise the client’s awareness of things he or she may be unaware of, e.g. physical gestures, tone of voice, eye contact. Although in one sense this appears less liable to coach bias than CB, the gestalt coach nevertheless offers selective rather than total observations based on what he or she notices and this too could lead to bias that feels unethical or unfitting.

Awareness

Gestalt coaching proposes a paradoxical theory of change, a notion that growth (i.e. becoming) is achieved through raised awareness (i.e. of being). I couldn’t find research that tested this hypothesis clinically; e.g. whether raising awareness necessarily leads to change and, if so, what kind of change; whether awareness alone is sufficient to motivate and sustain change; whether awareness will always result in choices and decisions that serve the best interests of the client and others.

Like gestalt, CB encourages experimentation aimed primarily at raising awareness of erroneous beliefs by challenging assumptions and exposing the client to situations where his or her assumptions about reality are tested. In this sense, CB seeks to adopt a scientific approach in conjunction with the client; testing, confirming or refuting his or her beliefs.

The main limitation of a CB approach is when working with clients dealing with deep existential or spiritual issues and questions that can’t be tested empirically or in cultural environments that may limit what questions are culturally appropriate or permissible. This challenge is particularly pertinent in the organisation in which I work, operating globally from a Christian spiritual base in diverse cross cultural contexts where existential/spiritual questions are often paramount (e.g. disaster zones, fragile states, severe poverty areas).

Reality

As a problem-solving and solutions-focused approach, CB coaching is particularly interested in correcting cognitive distortions, that is, beliefs that don’t correspond with reality. Social constructionists challenge this notion of reality, asserting that reality isn’t something the client discovers but, rather something that is co-created between the client and coach. To reframe a situation in such a way that challenges and changes previous assumptions is regarded as just that; a reframing rather than a revealing.

A related objection is CB’s traditional focus on addressing negative cognitions and emotions. This draws attention to specific remedial aspects of a client’s experience and attributes meaning and significance to them. A positive psychology or appreciative inquiry-based coaching model would challenge this focus, drawing corresponding attention to positive aspects of a client’s outlook, experience and capability. Perhaps there is room to build an eclectic model that draws on both approaches.

A similar social constructionist challenge could be posed to the gestalt notion of ‘need’ as fundamental driver of human motivation and satisfaction. To what degree is this model and the psychological process it describes a construct superimposed onto human experience as much as an insight derived from it; that is, to what degree is this process socially constructed rather than a description of ‘reality’ per se?

Conclusion

Gestalt and cognitive behavioural psychology have powerful applications to coaching. Both have an underlying optimistic outlook, a belief in the possibility of clients to grow in awareness and understanding of their own cognitive, emotional, physical and behavioural experiences and processes, to break through psychological and behavioural blockages and limitations to reach their personal and work goals.

Both schools focus primarily on the present moment, the client in the moment, the transformational potential of relationship in the here-and-now to release fresh opportunities in the future. As profoundly interpersonal disciplines, they rely on human presence, trust and connection, using oneself as instrument in the coaching relationship to bring about change.

Different approaches work well for different clients in different circumstances. Gestalt as an experiential and experimental approach can reveal insights that may not be reached through more conventional cognitive-conversational approaches. However, it demands of the coachee a willingness to explore emotional and physiological experience that may feel alien or uncomfortable for some people.

The CB approach is currently one of the most popular therapeutic practices in the UK, partly because of its ability to achieve change in a client’s thinking and behaviour quickly. However, it assumes a rational state that is sometimes difficult for coaching clients to achieve when experiencing high levels of anxiety or stress, in which case combining CB with, say, techniques from Human Givens could be advantageous.

Important spiritual and existential questions lie out of scope for gestalt and CB and both schools need particularly sensitive application in cross-cultural environments. Nevertheless, my research and personal experience convince me that gestalt and CB schools alike can provide valuable insights, frameworks and techniques to enhance coaching with individuals, groups and organisations.

The CB coach may work with the same client introduced in the gestalt example above by helping her surface what conclusions she has drawn from this experience (e.g. ‘If I get into conflict, I won’t be able to deal with it, therefore it’s best to stay away from situations that could lead to conflict’) and how these beliefs are influencing her behaviour (e.g. in this case, ‘avoid situations with potential for conflict’).

The coach may then challenge her to explore the validity of these beliefs (e.g. ‘are there situations in which you have successfully resolved or coped with conflict?’) and encourage her to experiment with new behaviours that lead to more constructive ways of dealing with relationships in the future.

These examples illustrate how gestalt and CB pay attention to how the client is experiencing a situation or relationship in the here-and-now. In practice, both these schools tend to be interested in the past or future only insofar as they exert influence in the present.

Experience

Gestalt practitioners refer to the client environment as the field. The field is the total context of a person’s internal and external experience, which includes the presence and influence of the coach in that person’s experience. Helping the client explore his or her field focuses on raising the client’s awareness of how he or she experiences and configures that environment subjectively based on his or her beliefs, thoughts, interpretations, feelings etc, e.g. ‘What am I experiencing?’, ‘What sense am I making of my experience?’ and ‘How is my experience influencing me in the present?’

The notion of field in gestalt relates to another central concept, figure and ground, where figure is that which emerges at any one time for a person or group and captures the attention vs ground as the backdrop to the figure that tends to go unnoticed. A gestalt coach may both help raise the client’s awareness of what is figural in the moment (e.g. the presenting issue or story) and explore the ground (e.g. how the client is feeling as he or she relates the story, what other ‘stories’ he or she is part of) as a means to evoking fresh awareness and insight.

When exploring the ground, the coach may pose questions that feel paradoxical, e.g. ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What isn’t featuring in the story?’, ‘What are we not talking about?’ or invite the client experimentally to physically demonstrate or role play aspects of his or her experience to see and feel what emerges. The coach may also offer observations (‘I notice...’) or self reflections (‘As you said that, I felt X’), using him or herself as part of the client field to raise the client’s awareness and insight.

This requires of the coach a high level of self-awareness, commitment to the client relationship and interpersonal skill to enhance the client’s awareness and development and avoid introducing unhelpful interference in the coaching process.

Another common gestalt method involves inviting the client to engage in experiments that exaggerate the client’s feelings. For example, if the client displays physical postures or movements whilst talking about his or her goals, thoughts or feelings, the coach may reflect this observation back to the client and invite him or her to exaggerate that posture or movement, thereby amplifying its effects, and see what fresh insight emerges.

A corresponding CB coach may typically enable a client to explore his or her experience using a conceptual model, e.g. SPACE framework, where S denotes Social context, how the client is performing within his or her context; P denotes Physical, what the client is experiencing physiologically; A denotes Action, how the client is behaving in his or her context; C denotes Cognitions, what perceptions and beliefs he or she holds in that environment; E denotes Emotions, how he or she is feeling.

The intention is to raise the client’s awareness of what he or she is experiencing in each dimension and how the client’s cognitions and behaviours are impacting on what he or she is experiencing. In this sense, the client is viewed systemically (cf gestalt field above); he or she is not only subject to the influences of his or her environment but also shapes that environment by how he or she perceives, behaves and acts within it.

As the client relates the situation or experience, the CB coach may offer observations or questions aimed at helping surface or crystallise the client’s underlying beliefs of assumptions. Again, as in gestalt coaching, this requires a high level of sensitivity and trust in the coach-client relationship. The coach may then present further questions aimed at challenging the validity of the client’s beliefs; not in terms of whether they are essentially ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ but in terms of how far they are supported by evidence, the ‘facts’.

The goal behind each question is to enable the client to gain a truer perspective, where ‘true’ = greater correlation with reality. I will comment on a social constructionist challenge to notions of objective reality under ‘critique’ below.

On one occasion, I approached a CB coach because I was experiencing unresolved conflict with a colleague, felt frustrated at my inability to resolve matters and, over time, tended to avoid her. After describing the relationship and how I was feeling within it, the coach posed a number of questions, common to CB coaching practice, aimed at challenging my evaluations and attributions in this relationship:

*Over-generalisation: e.g. was I generalising every interaction I had with the colleague as characterised by conflict, and ignoring exceptions’ (cf ‘what am I not noticing?’ in gestalt)?

*Fortune-telling: was I assuming that it would all go horribly wrong every time we meet, as if I could predict the future?

*Personalisation: was I taking sole responsibility for difficulties in the relationship rather than recognising my colleague’s contribution too?

*Catastrophising: e.g. did I typically anticipate worst case scenarios as I approached this colleague, rather than allowing for other possibilities to emerge?

*Mind-reading: e.g. was I making assumptions about her thinking based on my own interpretations of her behaviour?

Having explored my beliefs and thinking patterns, the CB coach encouraged me to test my own assumptions by engaging in cognitive and behavioural experiments, e.g. by meeting with the colleague and making a conscious note each time she behaved differently to how I expected; noticing how she behaved with other people and how they responded; smiling as I approached her, vividly imagining a positive experience, taking note of the result; asking her directly what she was thinking rather than assuming I already knew.

The goal of this kind of experimentation is to establish and reinforce new beliefs, thought patterns and behaviour that are more reality-based and, therefore, less dysfunctional and more constructive for the client, opening up fresh possibilities for the future. It entails developing the client’s own thinking skills, enabling him or her to identify limiting thoughts in the future and take intentional steps to address them.

In this example, I was able to develop a new sense of perspective on myself, my colleague and the relationship between us. Although it continued to be a difficult relationship, I felt more free within it, more able to be myself, more able to recognise when things went well, more able to differentiate my own contribution from hers in what happened between us. As a result, I felt less nervous about meeting with her, less inclined to avoid her, more able to reach out towards her in constructive ‘adult-adult’ mode.

As illustrated by these examples, gestalt and CB both seek to harness the power of imagination, gestalt by experimenting and possibly enacting (e.g. via drama or role play) and CB by visualising or vividly imagining new scenarios. In gestalt, the power of insight and change often comes from physically doing something within the coaching encounter itself, in CB by mentally ‘doing’ it or going away and practising a new behaviour or approach.

Holism

Gestalt may be regarded as distinctive and unusual in Western culture by its characteristic attention to the body. At one end of the spectrum, some gestalt practitioners regard the mind as an interference to insight and awareness because it can be so misleading and self-deceiving. Others regard the body and psyche as identical.

In gestalt, the body is regarded as a means by which need may be expressed genuinely and without conscious realisation, unfiltered by what Freud refers to as the superego. I have a personal coaching example:

I was working with a gestalt coach, as client, and commented that I felt anxious about approaching a forthcoming presentation to an executive team. Rather than suggesting we discuss this, the coach invited me to stand, role play walking into the executive team meeting and show him what feeling anxious might look like. As I enacted this scenario, he commented that I was holding my right hand across my chest, as if covering my heart. I had no awareness of this until he mentioned it.

We then explored what ‘covering my heart’ might mean symbolically. I became aware that I characteristically presented to this particular team in highly detached, rational-analytical mode and never really expressed my heart, how passionate I felt about what I was presenting on, how much it mattered to me personally. The coach suggested role play the scenario with my right hand in a more open position, thereby ‘revealing my heart’, and to rehearse speaking to the hearts rather than the minds of the executive team.

The subsequent meeting with the executive team was very different to anything I had experienced previously. It felt more human than technical, I received strong support for my proposal and felt supported personally too. The team was highly engaged and I left feeling confident and encouraged. The experience demonstrated powerfully to me that the body itself can convey valuable subconscious messages that lie outside of conscious awareness and that paying attention to the body can yield profound results.

CB too pays attention to the client’s physical experience (see SPACE model above), albeit primarily as a data source for what the client may be thinking and feeling or to see how it could be impacting on the client’s mental an emotional state. I believe recent research into rationality and intuition could help build a bridge between cognitive, emotional and physiological dimensions of experience, e.g. explaining how intuitive insight is often experienced somatically and expressed using physical-metaphorical language, e.g. ‘hunch’, ‘gut feeling’.

Critique

Bias

The CB coach is more likely than his or her gestalt counterpart to offer a theoretical framework along with a tentative ‘diagnosis’, implying an interpretation, of the client condition along with a proposed action plan; thereby acting as expert or personal development mentor. he risk is that the CB coach could superimpose his or her own values or frame of reference on the client in such a way that feels unethical or unfitting, particularly in cross-cultural environments.

The gestalt coach is more likely to offer observations, ‘I notice...’ without interpretation, aiming to raise the client’s awareness of things he or she may be unaware of, e.g. physical gestures, tone of voice, eye contact. Although in one sense this appears less liable to coach bias than CB, the gestalt coach nevertheless offers selective rather than total observations based on what he or she notices and this too could lead to bias that feels unethical or unfitting.

Awareness

Gestalt coaching proposes a paradoxical theory of change, a notion that growth (i.e. becoming) is achieved through raised awareness (i.e. of being). I couldn’t find research that tested this hypothesis clinically; e.g. whether raising awareness necessarily leads to change and, if so, what kind of change; whether awareness alone is sufficient to motivate and sustain change; whether awareness will always result in choices and decisions that serve the best interests of the client and others.

Like gestalt, CB encourages experimentation aimed primarily at raising awareness of erroneous beliefs by challenging assumptions and exposing the client to situations where his or her assumptions about reality are tested. In this sense, CB seeks to adopt a scientific approach in conjunction with the client; testing, confirming or refuting his or her beliefs.

The main limitation of a CB approach is when working with clients dealing with deep existential or spiritual issues and questions that can’t be tested empirically or in cultural environments that may limit what questions are culturally appropriate or permissible. This challenge is particularly pertinent in the organisation in which I work, operating globally from a Christian spiritual base in diverse cross cultural contexts where existential/spiritual questions are often paramount (e.g. disaster zones, fragile states, severe poverty areas).

Reality

As a problem-solving and solutions-focused approach, CB coaching is particularly interested in correcting cognitive distortions, that is, beliefs that don’t correspond with reality. Social constructionists challenge this notion of reality, asserting that reality isn’t something the client discovers but, rather something that is co-created between the client and coach. To reframe a situation in such a way that challenges and changes previous assumptions is regarded as just that; a reframing rather than a revealing.

A related objection is CB’s traditional focus on addressing negative cognitions and emotions. This draws attention to specific remedial aspects of a client’s experience and attributes meaning and significance to them. A positive psychology or appreciative inquiry-based coaching model would challenge this focus, drawing corresponding attention to positive aspects of a client’s outlook, experience and capability. Perhaps there is room to build an eclectic model that draws on both approaches.

A similar social constructionist challenge could be posed to the gestalt notion of ‘need’ as fundamental driver of human motivation and satisfaction. To what degree is this model and the psychological process it describes a construct superimposed onto human experience as much as an insight derived from it; that is, to what degree is this process socially constructed rather than a description of ‘reality’ per se?

Conclusion

Gestalt and cognitive behavioural psychology have powerful applications to coaching. Both have an underlying optimistic outlook, a belief in the possibility of clients to grow in awareness and understanding of their own cognitive, emotional, physical and behavioural experiences and processes, to break through psychological and behavioural blockages and limitations to reach their personal and work goals.

Both schools focus primarily on the present moment, the client in the moment, the transformational potential of relationship in the here-and-now to release fresh opportunities in the future. As profoundly interpersonal disciplines, they rely on human presence, trust and connection, using oneself as instrument in the coaching relationship to bring about change.

Different approaches work well for different clients in different circumstances. Gestalt as an experiential and experimental approach can reveal insights that may not be reached through more conventional cognitive-conversational approaches. However, it demands of the coachee a willingness to explore emotional and physiological experience that may feel alien or uncomfortable for some people.

The CB approach is currently one of the most popular therapeutic practices in the UK, partly because of its ability to achieve change in a client’s thinking and behaviour quickly. However, it assumes a rational state that is sometimes difficult for coaching clients to achieve when experiencing high levels of anxiety or stress, in which case combining CB with, say, techniques from Human Givens could be advantageous.

Important spiritual and existential questions lie out of scope for gestalt and CB and both schools need particularly sensitive application in cross-cultural environments. Nevertheless, my research and personal experience convince me that gestalt and CB schools alike can provide valuable insights, frameworks and techniques to enhance coaching with individuals, groups and organisations.