Just do it

Wright, N. (2012), ‘Just Do It – A Case Study in Gestalt Experiential Coaching’, Industrial & Commercial Training, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, Vol 44, No2, pp67-74.

Hypothesis

That Gestalt-orientated coaching characterised by physically doing, as distinct from coaching characterised by conventional talking, can release and create powerful insight, energy and transformational potential.

Introduction

“Gestalt is distinct because it moves towards action, away from mere talk...through experiments, the (coach) supports the client’s experience of something new, instead of merely talking about the possibility of something new.” (Experimental Freedom in Wiki, 2011)

Doing something is qualitatively different to thinking about it or even talking about it. Doing has an impact on what I’m thinking and feeling. I’m working on a difficult mental problem, I feel stuck, I go for a walk and physical movement seems to create psychological movement, allowing fresh insight and ideas to emerge. I feel energised and motivated to tackle the problem in a new way.

In this vein, I feel inspired and intrigued by Gestalt’s approach to experimentation and improvisation, its emphasis on creating vibrant, risky, here-and-now opportunities, ‘safe emergencies’ for exploration and awareness-raising (Zinker, 1977; Clarkson, 1999).

For this case study, I invited Paul to be my client, a leader in a global, non-governmental organisation who had worked with executive coaches from psychodynamic and cognitive behavioural schools. We were both interested to see how he might experience and benefit from a more experiential approach.

Theory

I drew on psychological research from a range of sources, including Gestalt psychology, therapy and coaching (e.g. Zinker, 1977; Clarkson, 1999), intuition (e.g. Sadler-Smith, 2004, 2008), body work (Ernst & Goodison, 1981), learning styles (e.g. Honey & Mumford, 2000) and experiential learning (e.g. Kolb in Smith, 2001; Beard & Wilson, 2002).

A limitation of traditional conversation-based coaching is that a client’s mind may unconsciously filter or suppresses knowledge that he or she considers unacceptable or unbearable. If the coach tries to surface this knowledge, he or she can evoke defensive routines, expressed as some form of resistance (Clarkson, 1999).

Alternatively, a client’s mind may become blinkered or fixated, focusing only on that which captures his or her immediate attention or imagination (figure) and unaware of what lies behind (ground and field), the ‘what else’ of a client’s experience (Yontef, 1993; Parlett, 1999).

Physically acting out can raise hidden, repressed, tacit or subconscious knowledge into conscious awareness. The body bypasses psychological filters and defences and ‘speaks’ in the here-and-now that which the mind may have rendered unspeakable, or reveals underlying issues and aspirations that otherwise lie outside of the client’s awareness (Ernst & Goodison, 1981).

Research into intuition sheds light on the profound relationship between physical experience and knowledge. It’s as if the body can retain and release tacit knowledge acquired by implicit learning, that is, learning by experience. Intuition is often described using physiological language, e.g. ‘hunch’ or ‘gut feel’. Sadler-Smith comments that “gut feelings are inevitable, but effective learning from them is not.” (2004, p84). A coach needs to learn how to recognise and use intuition effectively and to enable the client to do the same.

Reichian bodywork similarly recognises how people commonly use somatic language to express psycho-somatic phenomena, e.g. stiff upper lip, carrying the world on one’s shoulders, behaving spinelessly, putting on a brave face. A bodywork coach will enable a client to explore his or her experience by experimenting with physical posture or movement, noticing what emerges, then seek to enable to the client to make sense of that observation. (Ernst & Goodison, 1981).

A challenge in coaching is therefore is to create a suitable catalytic opportunity that enables both physically acting out and sense-making, “decoding messages from the body” (Corey, 1996; Joyce & Sills, 2010, p148). Some coaches encourage clients to give parts of the body a ‘voice’. A Gestalt coach may create experiments that involve the client acting out an experience or a scenario to see what emerges into awareness by physically doing it (Zinker, 1977, Clarkson, 1999).

The Gestalt coach may draw the client’s attention to his or her physicality; physical movements, gestures, postures, emotional expression etc, encouraging the client to exaggerate or ‘stay with’ in order to amplify or intensify them. In doing so, such interventions enable the client to establish contact with his or her own immediate experience, the underlying psychological and emotional state, and thereby surface it into conscious awareness (Corey, 1996; Clarkson, 1999).

Similarly, the coach may encourage the client to practise new scenarios or to experiment with new experiences in order to develop the confidence and capability needed to embrace fresh opportunities and challenges in the future (Corey, 1996; Clarkson, 1999). The approach is immediate and active, characterised by ‘try X’ rather than ‘how would it be if you were to try X’. It enables embedment of learning by integrating it holistically into the client’s psycho-somatic experience.

Gestalt’s emphasis on experimentation is an activist and experiential approach; it involves learning by doing (Honey & Mumford, 2000). Beard & Wilson describe experiential learning as, “creating a meaningful learning experience” (2002, p1). The value of experiential learning lies in sense-making through experiencing. I believe Gestalt-orientated coaching offers opportunities for experiencing, sense-making and profound re-experiencing as a route to transformational development.

Practice

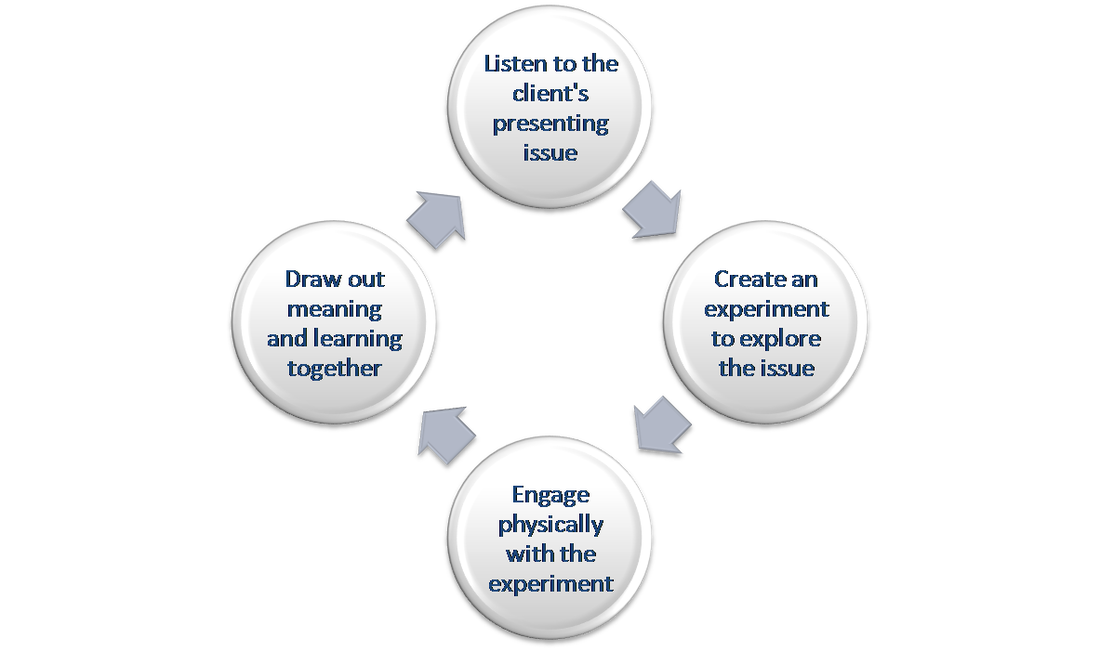

Based on this research, I developed a simple reflective practice framework to guide my coaching sessions with Paul (Figure 1). We had 3 x 1hr sessions within a 2-week timeframe, with 15 minutes at the end of each session to review and capture learning.

Sadler-Smith describes intuition as, “a capacity for attaining direct knowledge or understanding without the apparent intrusion of rational thought...a form of knowing that manifests itself as an awareness of thoughts, feelings or bodily sense.” (2004, pp77 & 81)

Figure 1

Session 1 – polarities

Paul wanted to enhance his leadership. As he spoke, I noticed key words that seemed to carry an underlying resonance, e.g. feel driven, get carried away, speaking in passive voice. I wondered what an active reframing might look and feel like if enacted as a polarity (driven vs driving), what insights might emerge, how this might shift Paul’s self-concept and behaviour as a leader.

I walked to one end of the room. This place represented Paul as driver, fully in control, not driven or controlled by anyone or anything else. I then walked to the other end of the room. This place represented Paul as driven, not in control, driven and controlled by circumstances or others. I invited Paul to join me on the continuum.

Paul immediately walked towards the ‘driven’ place, paused as he approached it and looked tearful. “Woah, this is strange, I feel really emotional here.” I encouraged him to stay with the emotion, to experience the feeling of contact with it and to depict what it might look like physically.

He pulled up a chair, sat on it with eyes closed, bent forward with head in hands. I asked what he noticed. “It feels like a foetal position.” I mirrored his posture and commented how it looked and felt like a closed posture, an attempt to withdraw to a safe internal space, how one might protect oneself from physical attack.

I invited him to move to the opposite polarity. He did so and immediately looked more relaxed, standing upright, shoulders back and head up. I asked him what he noticed, how she felt. “More relaxed, more confident.”

I invited Paul to stand on the polarity where he wants to be. He moved towards the ‘driven’ end again. “I feel like I’m here but I desperately don’t want to be.” I encouraged him to sit back in the same seat as before but this time to stay in ‘driver’ mode. He sat in the seat but still looked despondent. “I don’t want to be here, it feels like a dark place.”

So we returned to the ‘light’ place and I invited him to look back at the dark place. “What do you want to say to the dark place from here?” “I want to tell it to ‘f***off’ but I can hardly bring myself to say it.” I encouraged him to give it a go, and he did. It sounded powerful and releasing as he shouted at the other end of the room. He started to laugh loudly and freely. “Is there anything else you want to say or do, Paul?” “Yes!” He threw his pen at that end of the room then rushed over confidently and kicked the chair he had been sitting on.

For a moment, Paul stayed in that space. “I can’t believe it, it feels so different standing here now.” He was still laughing loudly, looked almost intoxicated with his new sense of freedom, very excited and physically animated. “I feel so released!” I mirrored his posture and invited him to stay in that space for a moment, to feel that feeling, to really feel the contact with it, before closing off this session together.

Session 2 – representations

Paul began by telling me about a course he once attended on leadership and some of the qualities he wants to develop. I suggested we could explore these qualities as something within Paul or, alternatively, we could explore how he wants to exercise leadership within the actual system within which he already operates. He was interested in the latter option.

I poured out a bag of toy figures on the table and invited him to choose which figures best represented people in his ‘system’ at work. Paul quickly picked up figures representing his director (a dragon), himself and his three direct reports. He placed them in a hierarchical arrangement which, he said, mirrored the organisation’s structure chart.

I asked him, “Is there anyone else?” He looked tearful. “Yes, my family”. I asked Paul where he would place his family. He placed them outside of the hierarchy, then reflected for a moment and moved them into the centre of the structure alongside the figure that represented himself. He commented, “It feels like they are in that place with me.” I reflected this back, “What does it mean for them to be with you in this way?” He replied, “I carry leadership responsibility in all aspects of my life.”

I suggested that Paul walk around the room, look at his portrayal of the leadership system from different angles, different points of view. He did so, then I asked him to comment on what he noticed. He immediately walked back to the toys and lifted the figure that represented himself out of the centre of the system and placed it outside. I asked him how it felt to move it there, to be there, out of the circle. “It feels like a guilty indulgence to be here, but it’s where I want to be. It makes me wonder whether I really want to be a leader.”

He paused for a moment, “I don’t want to stay in that place (outside the circle), but where I am at the moment feels unsustainable. I need to think about what resources I can draw on to get through it.” I commented that Paul speaks of himself as an isolated leader and that he placed the figures, apart from his family, at some distance from him and from each other. I suggested that he experiment with different configurations to see how that would feel and what insights could emerge. He did so.

I drew the session to a close by inviting Paul to consider what he would like to say to each person represented in the system. I placed each toy in turn in a chair opposite him so he could speak to it directly. Paul did this, but he looked and sounded bland and devoid of energy, passion and conviction as he did so. I inquired, “Where has all the passion and energy gone?” He responded, “I find it really hard to say what I’m thinking and feeling, even to myself.”

I asked if this resonated with his experience as a leader. He replied with a flash of insight, “Yes, I think this is the crux of the matter for me – how to express what I’m really thinking and feeling.”

Session 3 – role play

Paul arrived late and looked stressed. He spoke in monotone voice, describing pressure he was feeling from his director. I reflected this back, “I’m noticing how your voice sounds flat, monotone, as it was when you spoke to the figures at the end of the last session. At the same time, you are describing things that sound emotionally stressful and painful.” Paul agreed.

I asked Paul to think back to the first session. “Where on that polarity are you speaking from here and now?” “Pretty close to the dark side.” I proposed that we revisit the continuum, with Paul practising what he might say to the director at each point.

I played the director. Paul sat in a chair at the dark end of the polarity and explained the director stands over him as she speaks. I stood over him and started to say some of the kind of things she says. Paul immediately sat back in his seat, leaning away from me.

I asked, “What are you feeling?” He looked distressed, “Crushed, defeated.” I asked, “And what do you want to say to me (the director) from here?” He replied, “I don’t know what I’m feeling, I’ve repressed it. If I really allowed it to emerge, I would be fearful of losing my job.” I encouraged him to speak with all the passion he was feeling. He suddenly burst out with a series of swear words and immediately looked more relaxed, as if the experience had been cathartic.

I invited him now to move to the mid-point on the continuum. He sat down again in a chair and as I stood over him, Paul said he would prefer I sat down too so that we would feel more equal. In order to intensify the experience, however, I persevered with ‘directing’ him without sitting down. He looked and sounded passive and defeated again. I stepped out of role and invited him to consider what he could do differently to feel more equal, rather than what he would like the director to do. “I could stand up.” I suggested he did so then we replayed the scenario, standing together.

Paul appeared more confident standing, yet also defensive, pushing back against each thing I asked of him in role, rather than appearing to hear what I was feeling or asking for. I fed this back, how her responses landed with me as ‘director’, how I felt as though I wanted to push harder to get my point across. He looked surprised so I posed a question for reflection: “What are you contributing to what you are experiencing from your director?”

I suggested that Paul tune into what his director is feeling when she approaches him and that he respond to her in an open inquiring way. We practised a few statements, e.g. “Sounds like you have some concerns about whether I will complete the report on time. Is that how you are feeling?”

We then moved to the ‘light’ place. I invited him to sit down and to imagine me approaching him at his desk and to practise responding (a) as the bright side leader he aspires to be and (b) in an open physical, mental and emotional space, inquiring of her rather than reacting to her.

We ran this scenario and I fed back how his new approach landed for me and the response it evoked in me. Paul stood up as I approached, listened to what I had to say and reflected back what I seemed to be concerned about before trying to offer anything of his own material. I explained how this put me at ease, enabled me to speak with Paul in a more relaxed team-orientated mode. Paul looked amazed, “This feels like a breakthrough. I feel so more relaxed and confident now too.”

Analysis

I will focus this analysis on various Gestalt-orientated dimensions of this coaching experience: e.g. experimentation, engagement, use of self, contact, physicality, focus, impact. I will comment on each session in turn.

Session 1

The polarities idea came to mind when Paul spoke of his leadership in passive voice. On reflection, I could have invited Paul to say what his opposite to ‘driven’ would be, rather than proposing ‘driver’ myself, in order to explore further and reveal more of Paul’s own psychological construct and inner conflict (Zinker, 1977).

Paul and I were taken by surprise by the strength of the dynamic that emerged as soon as we began the physical experiment. The notion of polarity seemed to resonate for him and evoked a powerful emotional response as soon as he moved along it. The physical dynamic appeared to release an emotional dynamic that was previously unexpressed (Ernst & Goodison, 1981).

Paul commented how my animated walking alongside him, mirroring his movement and posture, created energy and helped him feel sufficient trust and confidence to engage fully in the experiment. I was in the experiment with him, not passively observing. My physical movement and mirroring also raised new insights into awareness for Paul, as if observing reflections of his own movement and posture in me helped him to see his own body language and expression in a fresh light.

I noticed how my literal-physical ‘use of self’ in the experiment alongside Paul raised awareness and insights within me as coach that I don’t think would have emerged if I had simply directed and observed in a more reflective ‘use of self’ mode (Clarkson, 1999; Cox, Bachirova & Clutterbuck, 2010). I felt fully tuned in, ‘in the zone’, moving freely with insight and ideas emerging on route as the process naturally unfolded.

Session 2

The representational idea using toy figures came to mind when Paul alluded to his leadership in personal-individual terms. I wanted to broaden his awareness of his systemic relational field at work, to enable him to explore, re-contextualise and ground his experience, perspective and practice as ‘leader’ within that environment (Nevis, 1987; Parlett, 1999).

Placing and configuring figures physically enabled a visual picture to emerge very quickly, a picture that represented Paul’s current perspective, psychological construct and experience of the system. As Paul and I moved to different parts of the room, we could each view Paul’s externalised system from different perspectives and share observations.

When Paul physically moved the figures, he experienced his leadership and relationship to others and the system very differently. This physical shift impacted him physically, emotionally and psychologically, raising his awareness of how he was feeling and why, what her fears and aspirations were. It also enabled him to explore new possibilities and how they might feel (Beard & Wilson, 2002).

Session 3

The role play idea came to mind when Paul focused on his relationship with his director and how he was experiencing it. My focus was on enabling Paul to establish contact with and express his emotional experience more dynamically and authentically (Clarkson, 1999; Cox, Bachirova & Clutterbuck, 2010; Joyce & Sills, 2010).

As the role play progressed, I became aware of how I was feeling as ‘director’ and how his behaviour was influencing how I was responding to him. This ‘use of self’ proved pivotal in raising Paul’s awareness. It shifted the focus from Paul’s intrapersonal experience to Paul’s and the directors’ interpersonal experience. It also provided opportunity to rehearse alternative scenarios and behaviours.

Reconnecting in this final session with the polarities we had established in the first session, using the same spaces in the room as we had done before, provided a sense of continuity and movement towards completion. Revisiting the continuum and physically role-playing along it towards the ‘bright’ end provided Paul with opportunity to draw on the combined power of fresh awareness, insight, emotional experience and behaviour to achieve motivation and change (Corey, 1996).

Evaluation

The most striking learning for me through this coaching experience was how doing with Paul made the whole coaching dynamic profoundly experiential for both of us. Moving, acting and interacting with the client throughout opened up access to new insights and ideas for me, as well as the client, in ways I hadn’t expected. This is a form of ‘use of self’, a physical mutual engagement, quite different to traditional observing and reflecting.

The experimental approach had powerful physical, psychological and emotional impacts on Paul. He commented afterwards that my physically acting out with him, using the physical space together, gave him the confidence to engage fully without feeling embarrassed or inhibited.

The fact that Paul and I already had a relationship of trust accelerated the pace at which he felt able to engage in the experiments. If I was working with a client where there was no prior relationship, I would have to pay closer attention to building relationship and trust first.

I suggested each of the experiments we used. It provided a guiding framework for experimentation. If I were to work with a client over a longer period or for a greater number of sessions, however, I would want to engage the client in co-creating experiments as a way of ensuring on-going resonance for the client and strengthening the co-active dimension.

Paul found the coaching experience powerful and energising. The Gestalt approach surfaced and created fresh insight for him, allowed deeper emotional contact and catharsis and provided new behavioural experiences and alternatives. I plan to revisit this experience with Paul in 3 months to evaluate how this coaching intervention has impacted both Paul and his relational system.

Conclusion

Clarkson’s opening words in her book, Gestalt Counselling in Action (1999) articulate well how I struggled to capture and express the vibrant power and essence of this coaching experience in written case study form: “I painfully experience the chasm between the vividly alive encounter with another human being and the pale static representation of the written word...”

Nevertheless, this research and experience has confirmed my initial hypothesis, and added to it. It has demonstrated how physically doing rather than just talking – enhanced now by doing with rather than just observing – can evoke powerful dynamics within and between coach and client, a synergy that releases fresh insight and energy and transformational potential.

I look forward to developing my practice further in the Gestalt-orientated coaching field.

Bibliography

Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2002) The Power of Experiential Learning. London, Kogan Page.

Clarkson, P. (1999) Gestalt Counselling in Action (2nd Edition). London, Sage Publications.

Corey, G. (1996) Theory and Practice of Counselling and Psychotherapy. 5th ed. California, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Cox, E, Bachkirova, T. & Clutterbuck, D. (2010) The Complete Handbook of Coaching. London, Sage.

Ernst, S. & Goodison, L. (1981) In Our Own Hands. London, The Women’s Press Ltd.

Gestalt Therapy. (2011). Experimental Freedom. [online]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestalt_therapy#Experimental_freedom [Accessed: 23 July 2011].

Honey, P. & Mumford, A (2000). The Learning Styles Helper’s Guide. Maidenhead, Peter Honey Publications.

Joyce, P. & Sills, C. (2010). Skills in Gestalt Counselling & Psychotherapy. London, Sage Publications.

Nevis, E. (1987) Organisation Consulting – A Gestalt Approach. Orleans, Gestalt Press.

Parlett, M. (1991) Reflections on Field Theory. The British Gestalt Journal. No1, pp68-91.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2004) The Intuitive Executive: Understanding and Applying Gut Feel in Decision Making. Academy of Management Executive, Volume 18, No4, pp76-91.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2008) Inside Intuition. Abingdon, Routledge.

Yontef, G. (1993) Awareness Dialogue & Process. Gouldsboro, Gestalt Journal Press.

Zinker, J. (1977) Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York, Random House.

Session 1 – polarities

Paul wanted to enhance his leadership. As he spoke, I noticed key words that seemed to carry an underlying resonance, e.g. feel driven, get carried away, speaking in passive voice. I wondered what an active reframing might look and feel like if enacted as a polarity (driven vs driving), what insights might emerge, how this might shift Paul’s self-concept and behaviour as a leader.

I walked to one end of the room. This place represented Paul as driver, fully in control, not driven or controlled by anyone or anything else. I then walked to the other end of the room. This place represented Paul as driven, not in control, driven and controlled by circumstances or others. I invited Paul to join me on the continuum.

Paul immediately walked towards the ‘driven’ place, paused as he approached it and looked tearful. “Woah, this is strange, I feel really emotional here.” I encouraged him to stay with the emotion, to experience the feeling of contact with it and to depict what it might look like physically.

He pulled up a chair, sat on it with eyes closed, bent forward with head in hands. I asked what he noticed. “It feels like a foetal position.” I mirrored his posture and commented how it looked and felt like a closed posture, an attempt to withdraw to a safe internal space, how one might protect oneself from physical attack.

I invited him to move to the opposite polarity. He did so and immediately looked more relaxed, standing upright, shoulders back and head up. I asked him what he noticed, how she felt. “More relaxed, more confident.”

I invited Paul to stand on the polarity where he wants to be. He moved towards the ‘driven’ end again. “I feel like I’m here but I desperately don’t want to be.” I encouraged him to sit back in the same seat as before but this time to stay in ‘driver’ mode. He sat in the seat but still looked despondent. “I don’t want to be here, it feels like a dark place.”

So we returned to the ‘light’ place and I invited him to look back at the dark place. “What do you want to say to the dark place from here?” “I want to tell it to ‘f***off’ but I can hardly bring myself to say it.” I encouraged him to give it a go, and he did. It sounded powerful and releasing as he shouted at the other end of the room. He started to laugh loudly and freely. “Is there anything else you want to say or do, Paul?” “Yes!” He threw his pen at that end of the room then rushed over confidently and kicked the chair he had been sitting on.

For a moment, Paul stayed in that space. “I can’t believe it, it feels so different standing here now.” He was still laughing loudly, looked almost intoxicated with his new sense of freedom, very excited and physically animated. “I feel so released!” I mirrored his posture and invited him to stay in that space for a moment, to feel that feeling, to really feel the contact with it, before closing off this session together.

Session 2 – representations

Paul began by telling me about a course he once attended on leadership and some of the qualities he wants to develop. I suggested we could explore these qualities as something within Paul or, alternatively, we could explore how he wants to exercise leadership within the actual system within which he already operates. He was interested in the latter option.

I poured out a bag of toy figures on the table and invited him to choose which figures best represented people in his ‘system’ at work. Paul quickly picked up figures representing his director (a dragon), himself and his three direct reports. He placed them in a hierarchical arrangement which, he said, mirrored the organisation’s structure chart.

I asked him, “Is there anyone else?” He looked tearful. “Yes, my family”. I asked Paul where he would place his family. He placed them outside of the hierarchy, then reflected for a moment and moved them into the centre of the structure alongside the figure that represented himself. He commented, “It feels like they are in that place with me.” I reflected this back, “What does it mean for them to be with you in this way?” He replied, “I carry leadership responsibility in all aspects of my life.”

I suggested that Paul walk around the room, look at his portrayal of the leadership system from different angles, different points of view. He did so, then I asked him to comment on what he noticed. He immediately walked back to the toys and lifted the figure that represented himself out of the centre of the system and placed it outside. I asked him how it felt to move it there, to be there, out of the circle. “It feels like a guilty indulgence to be here, but it’s where I want to be. It makes me wonder whether I really want to be a leader.”

He paused for a moment, “I don’t want to stay in that place (outside the circle), but where I am at the moment feels unsustainable. I need to think about what resources I can draw on to get through it.” I commented that Paul speaks of himself as an isolated leader and that he placed the figures, apart from his family, at some distance from him and from each other. I suggested that he experiment with different configurations to see how that would feel and what insights could emerge. He did so.

I drew the session to a close by inviting Paul to consider what he would like to say to each person represented in the system. I placed each toy in turn in a chair opposite him so he could speak to it directly. Paul did this, but he looked and sounded bland and devoid of energy, passion and conviction as he did so. I inquired, “Where has all the passion and energy gone?” He responded, “I find it really hard to say what I’m thinking and feeling, even to myself.”

I asked if this resonated with his experience as a leader. He replied with a flash of insight, “Yes, I think this is the crux of the matter for me – how to express what I’m really thinking and feeling.”

Session 3 – role play

Paul arrived late and looked stressed. He spoke in monotone voice, describing pressure he was feeling from his director. I reflected this back, “I’m noticing how your voice sounds flat, monotone, as it was when you spoke to the figures at the end of the last session. At the same time, you are describing things that sound emotionally stressful and painful.” Paul agreed.

I asked Paul to think back to the first session. “Where on that polarity are you speaking from here and now?” “Pretty close to the dark side.” I proposed that we revisit the continuum, with Paul practising what he might say to the director at each point.

I played the director. Paul sat in a chair at the dark end of the polarity and explained the director stands over him as she speaks. I stood over him and started to say some of the kind of things she says. Paul immediately sat back in his seat, leaning away from me.

I asked, “What are you feeling?” He looked distressed, “Crushed, defeated.” I asked, “And what do you want to say to me (the director) from here?” He replied, “I don’t know what I’m feeling, I’ve repressed it. If I really allowed it to emerge, I would be fearful of losing my job.” I encouraged him to speak with all the passion he was feeling. He suddenly burst out with a series of swear words and immediately looked more relaxed, as if the experience had been cathartic.

I invited him now to move to the mid-point on the continuum. He sat down again in a chair and as I stood over him, Paul said he would prefer I sat down too so that we would feel more equal. In order to intensify the experience, however, I persevered with ‘directing’ him without sitting down. He looked and sounded passive and defeated again. I stepped out of role and invited him to consider what he could do differently to feel more equal, rather than what he would like the director to do. “I could stand up.” I suggested he did so then we replayed the scenario, standing together.

Paul appeared more confident standing, yet also defensive, pushing back against each thing I asked of him in role, rather than appearing to hear what I was feeling or asking for. I fed this back, how her responses landed with me as ‘director’, how I felt as though I wanted to push harder to get my point across. He looked surprised so I posed a question for reflection: “What are you contributing to what you are experiencing from your director?”

I suggested that Paul tune into what his director is feeling when she approaches him and that he respond to her in an open inquiring way. We practised a few statements, e.g. “Sounds like you have some concerns about whether I will complete the report on time. Is that how you are feeling?”

We then moved to the ‘light’ place. I invited him to sit down and to imagine me approaching him at his desk and to practise responding (a) as the bright side leader he aspires to be and (b) in an open physical, mental and emotional space, inquiring of her rather than reacting to her.

We ran this scenario and I fed back how his new approach landed for me and the response it evoked in me. Paul stood up as I approached, listened to what I had to say and reflected back what I seemed to be concerned about before trying to offer anything of his own material. I explained how this put me at ease, enabled me to speak with Paul in a more relaxed team-orientated mode. Paul looked amazed, “This feels like a breakthrough. I feel so more relaxed and confident now too.”

Analysis

I will focus this analysis on various Gestalt-orientated dimensions of this coaching experience: e.g. experimentation, engagement, use of self, contact, physicality, focus, impact. I will comment on each session in turn.

Session 1

The polarities idea came to mind when Paul spoke of his leadership in passive voice. On reflection, I could have invited Paul to say what his opposite to ‘driven’ would be, rather than proposing ‘driver’ myself, in order to explore further and reveal more of Paul’s own psychological construct and inner conflict (Zinker, 1977).

Paul and I were taken by surprise by the strength of the dynamic that emerged as soon as we began the physical experiment. The notion of polarity seemed to resonate for him and evoked a powerful emotional response as soon as he moved along it. The physical dynamic appeared to release an emotional dynamic that was previously unexpressed (Ernst & Goodison, 1981).

Paul commented how my animated walking alongside him, mirroring his movement and posture, created energy and helped him feel sufficient trust and confidence to engage fully in the experiment. I was in the experiment with him, not passively observing. My physical movement and mirroring also raised new insights into awareness for Paul, as if observing reflections of his own movement and posture in me helped him to see his own body language and expression in a fresh light.

I noticed how my literal-physical ‘use of self’ in the experiment alongside Paul raised awareness and insights within me as coach that I don’t think would have emerged if I had simply directed and observed in a more reflective ‘use of self’ mode (Clarkson, 1999; Cox, Bachirova & Clutterbuck, 2010). I felt fully tuned in, ‘in the zone’, moving freely with insight and ideas emerging on route as the process naturally unfolded.

Session 2

The representational idea using toy figures came to mind when Paul alluded to his leadership in personal-individual terms. I wanted to broaden his awareness of his systemic relational field at work, to enable him to explore, re-contextualise and ground his experience, perspective and practice as ‘leader’ within that environment (Nevis, 1987; Parlett, 1999).

Placing and configuring figures physically enabled a visual picture to emerge very quickly, a picture that represented Paul’s current perspective, psychological construct and experience of the system. As Paul and I moved to different parts of the room, we could each view Paul’s externalised system from different perspectives and share observations.

When Paul physically moved the figures, he experienced his leadership and relationship to others and the system very differently. This physical shift impacted him physically, emotionally and psychologically, raising his awareness of how he was feeling and why, what her fears and aspirations were. It also enabled him to explore new possibilities and how they might feel (Beard & Wilson, 2002).

Session 3

The role play idea came to mind when Paul focused on his relationship with his director and how he was experiencing it. My focus was on enabling Paul to establish contact with and express his emotional experience more dynamically and authentically (Clarkson, 1999; Cox, Bachirova & Clutterbuck, 2010; Joyce & Sills, 2010).

As the role play progressed, I became aware of how I was feeling as ‘director’ and how his behaviour was influencing how I was responding to him. This ‘use of self’ proved pivotal in raising Paul’s awareness. It shifted the focus from Paul’s intrapersonal experience to Paul’s and the directors’ interpersonal experience. It also provided opportunity to rehearse alternative scenarios and behaviours.

Reconnecting in this final session with the polarities we had established in the first session, using the same spaces in the room as we had done before, provided a sense of continuity and movement towards completion. Revisiting the continuum and physically role-playing along it towards the ‘bright’ end provided Paul with opportunity to draw on the combined power of fresh awareness, insight, emotional experience and behaviour to achieve motivation and change (Corey, 1996).

Evaluation

The most striking learning for me through this coaching experience was how doing with Paul made the whole coaching dynamic profoundly experiential for both of us. Moving, acting and interacting with the client throughout opened up access to new insights and ideas for me, as well as the client, in ways I hadn’t expected. This is a form of ‘use of self’, a physical mutual engagement, quite different to traditional observing and reflecting.

The experimental approach had powerful physical, psychological and emotional impacts on Paul. He commented afterwards that my physically acting out with him, using the physical space together, gave him the confidence to engage fully without feeling embarrassed or inhibited.

The fact that Paul and I already had a relationship of trust accelerated the pace at which he felt able to engage in the experiments. If I was working with a client where there was no prior relationship, I would have to pay closer attention to building relationship and trust first.

I suggested each of the experiments we used. It provided a guiding framework for experimentation. If I were to work with a client over a longer period or for a greater number of sessions, however, I would want to engage the client in co-creating experiments as a way of ensuring on-going resonance for the client and strengthening the co-active dimension.

Paul found the coaching experience powerful and energising. The Gestalt approach surfaced and created fresh insight for him, allowed deeper emotional contact and catharsis and provided new behavioural experiences and alternatives. I plan to revisit this experience with Paul in 3 months to evaluate how this coaching intervention has impacted both Paul and his relational system.

Conclusion

Clarkson’s opening words in her book, Gestalt Counselling in Action (1999) articulate well how I struggled to capture and express the vibrant power and essence of this coaching experience in written case study form: “I painfully experience the chasm between the vividly alive encounter with another human being and the pale static representation of the written word...”

Nevertheless, this research and experience has confirmed my initial hypothesis, and added to it. It has demonstrated how physically doing rather than just talking – enhanced now by doing with rather than just observing – can evoke powerful dynamics within and between coach and client, a synergy that releases fresh insight and energy and transformational potential.

I look forward to developing my practice further in the Gestalt-orientated coaching field.

Bibliography

Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2002) The Power of Experiential Learning. London, Kogan Page.

Clarkson, P. (1999) Gestalt Counselling in Action (2nd Edition). London, Sage Publications.

Corey, G. (1996) Theory and Practice of Counselling and Psychotherapy. 5th ed. California, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Cox, E, Bachkirova, T. & Clutterbuck, D. (2010) The Complete Handbook of Coaching. London, Sage.

Ernst, S. & Goodison, L. (1981) In Our Own Hands. London, The Women’s Press Ltd.

Gestalt Therapy. (2011). Experimental Freedom. [online]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestalt_therapy#Experimental_freedom [Accessed: 23 July 2011].

Honey, P. & Mumford, A (2000). The Learning Styles Helper’s Guide. Maidenhead, Peter Honey Publications.

Joyce, P. & Sills, C. (2010). Skills in Gestalt Counselling & Psychotherapy. London, Sage Publications.

Nevis, E. (1987) Organisation Consulting – A Gestalt Approach. Orleans, Gestalt Press.

Parlett, M. (1991) Reflections on Field Theory. The British Gestalt Journal. No1, pp68-91.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2004) The Intuitive Executive: Understanding and Applying Gut Feel in Decision Making. Academy of Management Executive, Volume 18, No4, pp76-91.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2008) Inside Intuition. Abingdon, Routledge.

Yontef, G. (1993) Awareness Dialogue & Process. Gouldsboro, Gestalt Journal Press.

Zinker, J. (1977) Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York, Random House.

| Just Do It |