Team transformation

Wright, N. (2016). 'Team Transformation - Developing Teams Through Coaching', AICTP Journal, Association of Integrative Coach-Therapist Professionals, Issue 15, February, pp6-9.

Team coaching

Team coaching is just like individual coaching, except there are more individuals, right? Erm…yes, and no. Yes in the sense that you are working with individuals in a team since, after all, ‘team’ is a construct, an abstraction, a way of describing a group of individuals. No in that you are working with how they work with each other, in the moment, not just how they work with you. So that makes team coaching more complex and challenging. There’s greater opportunity too.

How often do we coach an individual – the two of us sitting in a room – and they describe what their team is like, what their line-manager is like, what their team colleagues are like? We hear their perspective, their narrative, their filtered experience…and we have no way of knowing for sure how well that reflects what happens when they actually meet with others for real. Team coaching provides opportunity to see and experience the system, the relationships at work.

I worked with one team where there was considerable conflict between two team members. I was invited to work with the team to help resolve the conflict. I met with the team leader first to scope out the work and, subsequently with team members individually. I noticed immediately that each person had his or her own view of what was happening, what was causing it, who was at fault, what needed to be done to fix it and who had to change their behaviour to make things work.

Psychological frames

Firstly, there are great insights from Gestalt that come into play here. You may be familiar with the notion of ‘figure and ground’, that is, figure is what we notice and what holds our attention; ground is the backdrop that often lies out of awareness. The team was transfixed on experiences when conflict had erupted and on what the two combatants did in those moments. They were not noticing how they and the rest of the team behaved in those moments and what effects that had.

Secondly, there are great insights from the psychodynamic field that provide a useful frame. Team members came from very different backgrounds professionally and organisationally. They each brought their own assumptions about how teams should work, what behaviours are appropriate at work, what role the leader should play, what roles other team members – including themselves should play. That’s a lot of ‘shoulds’ – and the assumptions behind them lay of awareness.

Thirdly, there are great insights from cognitive behavioural psychology. The team was under strain, people in the team feeling stressed. When people are stressed, it’s a bit like dust being kicked up from the ground emotionally. It prevents people thinking and seeing clearly and drives its members into fight, flight or freeze mode. It creates cognitive distortions too, meaning that people in the team became reactive, struggled to keep things in perspective and behaved irrationally as a result.

Team model

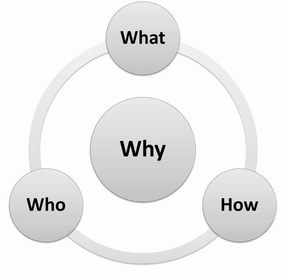

I’m going to pause here, step back from the case example and introduce a model that can provide a useful framework and compass for this kind of team working and team coaching scenario. I developed it after working with teams more intuitively, without an explicit framework, and noticing what seemed to make a difference to team inspiration and effectiveness. I’ve found that some teams find a conceptual framework useful to compare and test their own practice against.

The advantage of having a model like this in mind, even if we apply it loosely, is that it doesn’t focus on team pathology. It can be applied to teams in any state and in any context. The intention is not to force-fit a frame but to provide a prompt for conversation, for encouragement, for challenge, to build on and enhance team behaviour, practice and performance. Do feel free to use or adapt it for the specific people, organisations and cultures that you may work with. Notice what happens.

So, here we go. As an important principle when working with teams in organisations, I’m aware that the team doesn’t exist in a bubble, in a vacuum. It exists in a context and has a specific purpose, although it may have lost or not yet clarified that sense of purpose for itself (let alone others), or things may have changed in the context or the team itself that precipitate a need for change. This is a great place to start – focusing on the context that provides meaning and purpose for a team.

Applying the model

Here are some questions I may pose at the start of a conversation with a team:

- What is the organisation’s vision – by which I mean, what positive difference is it trying to make in the world (or: this country, this sector, this market, this community etc.)?

- What is the organisation’s strategy and what essential role does this team play in contributing to achieving it? (or: what would be missed if this team didn’t exist?)

- What are the organisation’s values and how do they influence the ways in which you work together and with others? (or: what could they look like if applied to your practice?)

Figure 1

I try to adapt the language I use to explain each dimension depending on who I’m working with and what language they use and connect with. Here’s how I do it. I’ve tried lots of ways with different teams but, so far, this 10-step method has achieved the best levels of understanding, engagement and development.

1. Invite the team leader to introduce the team development conversation: Why this, why now?

2. Draw the circles on a flip chart, using the words Why, What, How and Who as a starting point.

3. Explain that these are aspects of a team’s work that typically influence inspiration (how it feels to be part of the team) and effectiveness (how well it achieves its goals).

4. Hand out post it notes and pens to team members, inviting them to write down any questions, comments or ideas that occur to them as I describe, in brief, each dimension.

5. Introduce the dimensions in Why, What, How and Who sequence, posing questions that relate to each domain, and show how they interrelate together as a whole.

6. Invite team members to come forward once I’ve completed the introduction and to stick their post its on relevant circles.

7. Invite the team to come forward, look at the flipchart and discuss which dimensions or what they see on post-its resonate as most important for them – here and now – and why.

8. Ask them what specifically they would like to work on for e.g. the next hour.

9. Invite them do discuss and agree how they would like to do it, i.e. what method of working on the topic(s) they have prioritised will achieve the best result in the time available.

10. Encourage them to consider who is in the room and what they can do to include and draw on everyone’s insights and skills as they work on the task.

I have observed that using this approach, which involves an immediate application of the model, helps to embed a conceptual model in concrete experience. If I do this, I have noticed how often it moves a team beyond rational assent to an idea to emotional engagement with an experience. This is far more likely to drive their future behaviour and practice. While they work on the task, I interject with occasional insights and prompts that enable them to use the model with awareness.

Having completed the activity, I facilitate a review conversation during which I encourage team member to share their honest reflections on what happened; what influenced what happened; how it felt as they were working together; what role they and others played; what impact that had; what made the greatest positive difference; what they need/would like to do more of, more of the time in future meetings; what they are willing to take responsibility for to make sure that happens.

Posing questions

The key point is to pose evocative and provocative questions that enable a team to reflect on its practice. The questions aren’t fixed as it depends on the context and language that people use but here are some suggestions. I will relate the questions to each dimension of the model in order to give a sense of flow and coherence. If I work with a team over time, I post the model in the team meeting room and revisit it frequently at the start of, during and at the end of their meetings.

Why (purpose, goal)

In relation to the organisation’s vision, strategy and values:

• What’s our vision (or goal)?

• What are our greatest hopes?

• What are we here to do?

• What’s our role (or calling) – here and now?

• What’s important to us that we are trying to achieve?

• What would success look and feel like?

What (content, task)

In relation to our team’s Why:

• What are our priorities?

• Of all the things we could focus on, what is most important – here and now?

• What issues or tasks do we need to pay attention to?

• What are the questions that, if we could answer them, would take us forward?

• What would be the best use of our time together?

• What parameters do we need to take into account (e.g. budget, deadlines)?

How (method, process)

In relation to our team’s Why and What:

• How shall we do this?

• What would be the most effective method we could use?

• What way of tackling this would we find most creative and energising?

• What needs to happen first?

• Who else needs to be involved and when?

• Is this the best time for us to do this?

Who (people, relationships)

In relation to our team’s Why, Who and How:

• What gifts or talents (knowledge, expertise) does each of us bring to this?

• What do we need to know and understand to bring and draw out the best in each other?

• What’s the quality of contact between us as a team?

• What do we need to do to create enough trust between us to work together on this?

• What do we need – here and now – to do this well?

• Who else could we draw on to help us with this?

Grounding in practice

And now I return to the case example of the team I mentioned earlier this article. In order to reduce the level of emotional arousal, I reassured team members that I would be willing to walk with them on this journey and that I believed, I had hope, that change was possible. At the same time, I challenged and contracted with team members to be willing to reflect on their own contribution to what was happening and to be willing to take responsibility to work together to achieve the change.

At our first meeting together, I presented the model I have described above and fed back key themes I had noticed from individual conversations against each dimension. This provided opportunity to rationally ‘objectify’ their experience and proposed a common frame to work with. I also spoke to the intense emotions I had noticed in the team and explained, briefly, how this can affect what we notice (and don’t notice) and surface some of the assumptions we may hold.

I contracted with the team around how we would work together and then invited them to join me in a role play to evoke positive imagination: ‘We have now reached the end of this meeting – and it went brilliantly! Bearing in mind what we have just been thinking and talking about, what made this meeting so brilliant? How clear were we about what we are here to do? What did we focus on? How did we do it? What did you notice others doing? What did you notice about yourself?’

Team members joined in, hesitantly at first, then with tentative enthusiasm. Energy started to rise and, with it, the beginnings of a sense of hopeful optimism. I posed a challenge back to the team: ‘We each have a choice. How are you willing to conduct yourself for the next two hours so that, at the end of this time, what we have just imagined will be your actual experience? What do you need from each other to do this well?’ We discussed and contracted again…and then the team did it.

We met again for subsequent monthly team meetings. The team worked on its ordinary business but practised and learned to approach it with awareness, not defaulting to previous patterns or noticing and re-contracting when it did. In order to reinforce the change, we disrupted the team’s normal places of relating, moving to different rooms or venues to where they normally met, moving tables and seating into unexpected places etc. This too contributed to making the psychological shift.

Summary

I’ve described and approach to team coaching here presents the coach as an independent party who offers support and challenge to the team as a system. It rests on the coach’s ability to build rapport, credibility and trust with everyone in the team and on team member’s willingness to engage in making the change. It also demonstrates the value of psychological insight into people and team dynamics that can help address underlying personal, interpersonal and cultural dynamics.

I’ve also introduced a model of good practice that offers a mirror, a critical reflection, for the team and a flexible guide for the coach and team to work with together. It draws attention to the purpose of a team, what it focuses its attention on (or how it gets distracted), how it chooses to operate (by default or design) and the contribution and impact of individuals on each other and on the team as a whole. I hope you have found this useful and look forward to hearing readers’ comments.

I try to adapt the language I use to explain each dimension depending on who I’m working with and what language they use and connect with. Here’s how I do it. I’ve tried lots of ways with different teams but, so far, this 10-step method has achieved the best levels of understanding, engagement and development.

1. Invite the team leader to introduce the team development conversation: Why this, why now?

2. Draw the circles on a flip chart, using the words Why, What, How and Who as a starting point.

3. Explain that these are aspects of a team’s work that typically influence inspiration (how it feels to be part of the team) and effectiveness (how well it achieves its goals).

4. Hand out post it notes and pens to team members, inviting them to write down any questions, comments or ideas that occur to them as I describe, in brief, each dimension.

5. Introduce the dimensions in Why, What, How and Who sequence, posing questions that relate to each domain, and show how they interrelate together as a whole.

6. Invite team members to come forward once I’ve completed the introduction and to stick their post its on relevant circles.

7. Invite the team to come forward, look at the flipchart and discuss which dimensions or what they see on post-its resonate as most important for them – here and now – and why.

8. Ask them what specifically they would like to work on for e.g. the next hour.

9. Invite them do discuss and agree how they would like to do it, i.e. what method of working on the topic(s) they have prioritised will achieve the best result in the time available.

10. Encourage them to consider who is in the room and what they can do to include and draw on everyone’s insights and skills as they work on the task.

I have observed that using this approach, which involves an immediate application of the model, helps to embed a conceptual model in concrete experience. If I do this, I have noticed how often it moves a team beyond rational assent to an idea to emotional engagement with an experience. This is far more likely to drive their future behaviour and practice. While they work on the task, I interject with occasional insights and prompts that enable them to use the model with awareness.

Having completed the activity, I facilitate a review conversation during which I encourage team member to share their honest reflections on what happened; what influenced what happened; how it felt as they were working together; what role they and others played; what impact that had; what made the greatest positive difference; what they need/would like to do more of, more of the time in future meetings; what they are willing to take responsibility for to make sure that happens.

Posing questions

The key point is to pose evocative and provocative questions that enable a team to reflect on its practice. The questions aren’t fixed as it depends on the context and language that people use but here are some suggestions. I will relate the questions to each dimension of the model in order to give a sense of flow and coherence. If I work with a team over time, I post the model in the team meeting room and revisit it frequently at the start of, during and at the end of their meetings.

Why (purpose, goal)

In relation to the organisation’s vision, strategy and values:

• What’s our vision (or goal)?

• What are our greatest hopes?

• What are we here to do?

• What’s our role (or calling) – here and now?

• What’s important to us that we are trying to achieve?

• What would success look and feel like?

What (content, task)

In relation to our team’s Why:

• What are our priorities?

• Of all the things we could focus on, what is most important – here and now?

• What issues or tasks do we need to pay attention to?

• What are the questions that, if we could answer them, would take us forward?

• What would be the best use of our time together?

• What parameters do we need to take into account (e.g. budget, deadlines)?

How (method, process)

In relation to our team’s Why and What:

• How shall we do this?

• What would be the most effective method we could use?

• What way of tackling this would we find most creative and energising?

• What needs to happen first?

• Who else needs to be involved and when?

• Is this the best time for us to do this?

Who (people, relationships)

In relation to our team’s Why, Who and How:

• What gifts or talents (knowledge, expertise) does each of us bring to this?

• What do we need to know and understand to bring and draw out the best in each other?

• What’s the quality of contact between us as a team?

• What do we need to do to create enough trust between us to work together on this?

• What do we need – here and now – to do this well?

• Who else could we draw on to help us with this?

Grounding in practice

And now I return to the case example of the team I mentioned earlier this article. In order to reduce the level of emotional arousal, I reassured team members that I would be willing to walk with them on this journey and that I believed, I had hope, that change was possible. At the same time, I challenged and contracted with team members to be willing to reflect on their own contribution to what was happening and to be willing to take responsibility to work together to achieve the change.

At our first meeting together, I presented the model I have described above and fed back key themes I had noticed from individual conversations against each dimension. This provided opportunity to rationally ‘objectify’ their experience and proposed a common frame to work with. I also spoke to the intense emotions I had noticed in the team and explained, briefly, how this can affect what we notice (and don’t notice) and surface some of the assumptions we may hold.

I contracted with the team around how we would work together and then invited them to join me in a role play to evoke positive imagination: ‘We have now reached the end of this meeting – and it went brilliantly! Bearing in mind what we have just been thinking and talking about, what made this meeting so brilliant? How clear were we about what we are here to do? What did we focus on? How did we do it? What did you notice others doing? What did you notice about yourself?’

Team members joined in, hesitantly at first, then with tentative enthusiasm. Energy started to rise and, with it, the beginnings of a sense of hopeful optimism. I posed a challenge back to the team: ‘We each have a choice. How are you willing to conduct yourself for the next two hours so that, at the end of this time, what we have just imagined will be your actual experience? What do you need from each other to do this well?’ We discussed and contracted again…and then the team did it.

We met again for subsequent monthly team meetings. The team worked on its ordinary business but practised and learned to approach it with awareness, not defaulting to previous patterns or noticing and re-contracting when it did. In order to reinforce the change, we disrupted the team’s normal places of relating, moving to different rooms or venues to where they normally met, moving tables and seating into unexpected places etc. This too contributed to making the psychological shift.

Summary

I’ve described and approach to team coaching here presents the coach as an independent party who offers support and challenge to the team as a system. It rests on the coach’s ability to build rapport, credibility and trust with everyone in the team and on team member’s willingness to engage in making the change. It also demonstrates the value of psychological insight into people and team dynamics that can help address underlying personal, interpersonal and cultural dynamics.

I’ve also introduced a model of good practice that offers a mirror, a critical reflection, for the team and a flexible guide for the coach and team to work with together. It draws attention to the purpose of a team, what it focuses its attention on (or how it gets distracted), how it chooses to operate (by default or design) and the contribution and impact of individuals on each other and on the team as a whole. I hope you have found this useful and look forward to hearing readers’ comments.