The counselling supervisor

Wright, N. (2001) ‘The Counselling Supervisor’, The Christian Counsellor, April-June, Issue 9, pp21-24.

Introduction

In a previous article, I introduced the concept of supervision in interpersonal disciplines by summarising in outline:

What I mean by supervision

The relationship between supervision and other caring roles

Why supervision is important – including its potential benefits

I drew attention to the fact that the Bible describes Jesus Christ as ‘Supervisor’ (1Pe 2:25), along with church leaders (1Pe 5:2) as shepherds of God’s people. I also noted that in contemporary social work, pastoral and counselling fields, in spite of variations in approach and ethos, the notion of acting in some sense as ‘guardian’ of both supervisee and his/her work with clients is a common underlying theme.

In this article, I intend to expand on this subject area by exploring:

Key qualities of a good supervisor

Supervision models and approaches

Core supervision skills

Key qualities

I commented in the previous article that, “the most important resources that the counsellor brings to a relationship are his or her own qualities and abilities under the inspiration of the Spirit” and I believe that this, too, applies to the supervisor. The supervisors’ character, attributes and personal values have as much influence on what takes place in supervision as his or her professional skills.

Paul emphasises this point in 1 Timothy 3:1-7 and Titus 1:7-9 when he prescribes personal characteristics essential to a supervisor (‘over-seer’) within a pastoral context, including:

Holiness Love of the good

Patience Moderation

Respectability Openness to listen

Honesty Humility

Integrity Blamelessness

Self-discipline Gentleness

Reputability Ability to teach

Generosity Hospitality

These characteristics apply equally well to Christian supervisors in a diverse range of contexts since they describe, at heart, something of the character of Christ within us. The supervisor acts as role model for the supervisee (whether this is a conscious process or not) and the Biblical pattern is to model Christ himself as we walk in living relationship with Him (1 Cor 11:1).

Models and approaches

There are three principal approaches to supervision which, using distinctions identified by Batten (The Non-Directive Approach, 1988), may be characterised as follows:

Directive « Non-Directive « Positive Withdrawal

We can see these approaches illustrated in the life and ministry of Jesus Christ:

Directive: “This is what to do” (Mt 5:1-48)

Non-directive: “What do you think?” (Mt 16:13-1)

Positive withdrawal: “You do it” (Lk 10:1-12)

In general, a ‘directive’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisor has knowledge, information or experience needed by the supervisee. This is an approach that may be appropriate when, for instance, the supervisee is new to his or her role, a crisis situation has arisen or task deadlines are tight. For example:

Suzanne (supervisor) provided John (supervisee) with a copy of the agency’s counselling policy and asked him to make careful note of its contents.

A ‘non-directive’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisee already has adequate knowledge and information to fulfil his or her role but would, nevertheless, benefit from exploring specific issues in order to, for instance, gain greater insight or decide on an appropriate course of action. For example:

Peter (supervisor) acted as a sounding-board for Alison (supervisee), listening to her ideas and asking questions to stimulate deeper thought.

A ‘positive withdrawal’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisee may have adequate knowledge and information to fulfil his or her role but would grow in ability and/or confidence by being left to complete specific tasks without supervisory support. This is an approach that may be appropriate when, for instance, the supervisee needs to gain more practical experience. For example:

Caroline (supervisor) left the room in order to allow Janet (supervisee) to conduct her first pastoral counselling session alone with a client.

In real supervision practice, the supervisor may well use two or more of these approaches within the same session. The important principle at each stage of the process is to identify and use an approach that matches your intention. I find that, as a general rule, the following formula can be helpful, especially when planning a session beforehand:

“Which approach will be most facilitative –

For this supervisee?

In this situation?

At this time?”

Different approaches may be appropriate in different circumstances, even with the same supervisee, and this cautions the supervisor to review his or her approach at regular intervals.

There are numerous supervision models that draw on these approaches and which tend, in the main, to fall into one of the following categories:

Supervisor - Supervisee (1-1; cf individual counselling) (Mt 18:21f)

Supervisor - Team (group) (Mk 8:15-21)

Supervisor - Group (group; cf group therapy) (Mt 11:7-15)

Peer - Peer (one to one) (Ac 8:26-39)

Peer - Peer (group) (1 Th 5:11)

These models can be delineated further by examining their primary orientation/focus: task (what is done), person (who does it) and process (how it is done). The choice of model adopted by the supervisor is likely to be influenced by a number of factors which could include:

Aims (what he/she wants supervision to achieve)

Values (what he/she believes about supervisee development)

Culture (how supervision is done in his/her agency)

Tradition (how supervision has been conducted in the past)

Experience (which models he/she finds most familiar)

The model I use in my own freelance supervision practice is primarily non-directive and seeks to pay attention to all three dimensions of task, person and process (above). It also seeks to explore the supervisee’s work, ideas and experiences by drawing on the distinctive contribution of three key disciplines which interconnect: theological, psychological and sociological.

The theological dimension may, for instance, explore connections between what the supervisee experiences, plans, enacts etc. within the work role and what he or she believes Biblically. The psychological dimension may explore connections between the supervisee’s personal experience and how this influences his or her perspectives and practice. The sociological dimension may explore connections between the supervisee’s organisational and cultural context and how this influences what takes place in his or her work with clients.

The intention throughout is to enable the supervisee to grow in his or her ability to work as a reflective practitioner (that is, a person who acts consciously and deliberately on the basis of insight and understanding) – under the inspiration and guidance of the Holy Spirit.

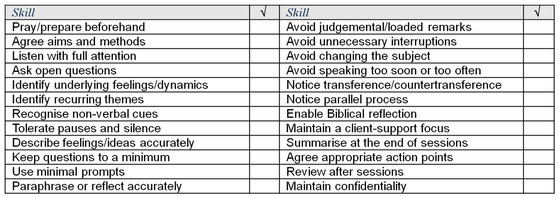

Skills

Many skills commonly associated with individual counselling (listening, reflecting, summarising etc.) are also core to the effective supervisor whereas additional skills (e.g. group facilitation) are vital for group-based models. James 1:19 (“be quick to listen, slow to speak”) could be regarded as a central maxim. The following skills list may serve as a helpful checklist, although you may want to include others that match your own particular approach and situation.

Introduction

In a previous article, I introduced the concept of supervision in interpersonal disciplines by summarising in outline:

What I mean by supervision

The relationship between supervision and other caring roles

Why supervision is important – including its potential benefits

I drew attention to the fact that the Bible describes Jesus Christ as ‘Supervisor’ (1Pe 2:25), along with church leaders (1Pe 5:2) as shepherds of God’s people. I also noted that in contemporary social work, pastoral and counselling fields, in spite of variations in approach and ethos, the notion of acting in some sense as ‘guardian’ of both supervisee and his/her work with clients is a common underlying theme.

In this article, I intend to expand on this subject area by exploring:

Key qualities of a good supervisor

Supervision models and approaches

Core supervision skills

Key qualities

I commented in the previous article that, “the most important resources that the counsellor brings to a relationship are his or her own qualities and abilities under the inspiration of the Spirit” and I believe that this, too, applies to the supervisor. The supervisors’ character, attributes and personal values have as much influence on what takes place in supervision as his or her professional skills.

Paul emphasises this point in 1 Timothy 3:1-7 and Titus 1:7-9 when he prescribes personal characteristics essential to a supervisor (‘over-seer’) within a pastoral context, including:

Holiness Love of the good

Patience Moderation

Respectability Openness to listen

Honesty Humility

Integrity Blamelessness

Self-discipline Gentleness

Reputability Ability to teach

Generosity Hospitality

These characteristics apply equally well to Christian supervisors in a diverse range of contexts since they describe, at heart, something of the character of Christ within us. The supervisor acts as role model for the supervisee (whether this is a conscious process or not) and the Biblical pattern is to model Christ himself as we walk in living relationship with Him (1 Cor 11:1).

Models and approaches

There are three principal approaches to supervision which, using distinctions identified by Batten (The Non-Directive Approach, 1988), may be characterised as follows:

Directive « Non-Directive « Positive Withdrawal

We can see these approaches illustrated in the life and ministry of Jesus Christ:

Directive: “This is what to do” (Mt 5:1-48)

Non-directive: “What do you think?” (Mt 16:13-1)

Positive withdrawal: “You do it” (Lk 10:1-12)

In general, a ‘directive’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisor has knowledge, information or experience needed by the supervisee. This is an approach that may be appropriate when, for instance, the supervisee is new to his or her role, a crisis situation has arisen or task deadlines are tight. For example:

Suzanne (supervisor) provided John (supervisee) with a copy of the agency’s counselling policy and asked him to make careful note of its contents.

A ‘non-directive’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisee already has adequate knowledge and information to fulfil his or her role but would, nevertheless, benefit from exploring specific issues in order to, for instance, gain greater insight or decide on an appropriate course of action. For example:

Peter (supervisor) acted as a sounding-board for Alison (supervisee), listening to her ideas and asking questions to stimulate deeper thought.

A ‘positive withdrawal’ approach is one which assumes that the supervisee may have adequate knowledge and information to fulfil his or her role but would grow in ability and/or confidence by being left to complete specific tasks without supervisory support. This is an approach that may be appropriate when, for instance, the supervisee needs to gain more practical experience. For example:

Caroline (supervisor) left the room in order to allow Janet (supervisee) to conduct her first pastoral counselling session alone with a client.

In real supervision practice, the supervisor may well use two or more of these approaches within the same session. The important principle at each stage of the process is to identify and use an approach that matches your intention. I find that, as a general rule, the following formula can be helpful, especially when planning a session beforehand:

“Which approach will be most facilitative –

For this supervisee?

In this situation?

At this time?”

Different approaches may be appropriate in different circumstances, even with the same supervisee, and this cautions the supervisor to review his or her approach at regular intervals.

There are numerous supervision models that draw on these approaches and which tend, in the main, to fall into one of the following categories:

Supervisor - Supervisee (1-1; cf individual counselling) (Mt 18:21f)

Supervisor - Team (group) (Mk 8:15-21)

Supervisor - Group (group; cf group therapy) (Mt 11:7-15)

Peer - Peer (one to one) (Ac 8:26-39)

Peer - Peer (group) (1 Th 5:11)

These models can be delineated further by examining their primary orientation/focus: task (what is done), person (who does it) and process (how it is done). The choice of model adopted by the supervisor is likely to be influenced by a number of factors which could include:

Aims (what he/she wants supervision to achieve)

Values (what he/she believes about supervisee development)

Culture (how supervision is done in his/her agency)

Tradition (how supervision has been conducted in the past)

Experience (which models he/she finds most familiar)

The model I use in my own freelance supervision practice is primarily non-directive and seeks to pay attention to all three dimensions of task, person and process (above). It also seeks to explore the supervisee’s work, ideas and experiences by drawing on the distinctive contribution of three key disciplines which interconnect: theological, psychological and sociological.

The theological dimension may, for instance, explore connections between what the supervisee experiences, plans, enacts etc. within the work role and what he or she believes Biblically. The psychological dimension may explore connections between the supervisee’s personal experience and how this influences his or her perspectives and practice. The sociological dimension may explore connections between the supervisee’s organisational and cultural context and how this influences what takes place in his or her work with clients.

The intention throughout is to enable the supervisee to grow in his or her ability to work as a reflective practitioner (that is, a person who acts consciously and deliberately on the basis of insight and understanding) – under the inspiration and guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Skills

Many skills commonly associated with individual counselling (listening, reflecting, summarising etc.) are also core to the effective supervisor whereas additional skills (e.g. group facilitation) are vital for group-based models. James 1:19 (“be quick to listen, slow to speak”) could be regarded as a central maxim. The following skills list may serve as a helpful checklist, although you may want to include others that match your own particular approach and situation.

Practical ideas and resources to enable supervisors to grow in each of the knowledge/skills areas listed here will be included in the final article of this supervision series.

Questions for reflection

The following questions are offered for reflection in light of the various issues raised in this article:

- Which of the characteristics described under ‘Key qualities’ are your strengths, and which may need further prayerful development?

- What values do you model in your work with supervisees? How are these values modelled in practice?

- How would you describe the aim(s) of your supervision practice?

- Which approach most accurately describes your general supervisory style: directive, non-directive or positive withdrawal?

- What are the potential implications (benefits/drawbacks) of your approach for your supervisees’ development?

- What tends to be the principal focus/orientation of your supervision (task, person, process) and what are the implications for your supervisee?

- How would you describe the model you use for your own supervision practice?

- Which skills do you consider to be your strengths and which may need further prayerful development?