The great divide

Wright, N. (1993) ‘The Great Divide’, Carer & Counsellor, CWR, Vol 3, No2, pp20-22.

It would probably be helpful for me to define broadly, from the outset, what I mean by these terms in order to avoid possible confusion. Allow me to do this by introducing ‘Jane’. Jane is a single parent living in a one-bedroom, high-rise flat with her two young children. The Local Authority moved her into the flat two years ago but, as her children have been frequently sick, she has had little opportunity to get out and meet new people.

The flat is damp and, in spite of her requests to have the necessary repairs carried out, the Local Authority has taken no action. Over the past few months, Jane has been feeling increasingly depressed and, at times, violent towards her children. How to you, as Christian community worker or counsellor, respond to this situation?

It seems to me that a similar process is likely to take place in both disciplines; that is, to help the client/group (a) explore the experience, (b) develop and understanding of the experience and (c) take appropriate action. The difference between the Christian counsellor and community worker is likely to be that the counsellor attempts to help Jane to handle the situation and to grow in Christ-likeness through it whereas the community worker attempts to help Jane, along with others in the community facing similar difficulties, to change the situation itself.

Note that both are looking for change in and for Jane; the difference is the individual ~ situational focus. This is clearly an over-generalisation but it may, nevertheless, serve to highlight similarity in methodology alongside a difference in emphasis. This counselling/community work relationship does, however, have its tensions; expressed well by Alan Billings in an article on tackling stress:

“I notice in my (theological college)…if we lay on courses in counselling or therapy, they are always oversubscribed. If you put on a programme that’s about community work skills or what’s happening in our towns or cities…nobody wants to come; but they do want to learn about counselling skills.

“Here is a sick person coming into a healing service, who is going to be prayed for and hands laid on and they are going to be healed, and they will go back home to unemployment, the slum building they are living in, to the one-parent family situation, and so on. It’s that kind of thinking, and the whole way of approach, that I really want to attack and say, “This won’t do.” This is really quite inadequate and its not the answer to our problems.

“My students at the college see stress as the inability of individuals to come to terms psychologically with some or other aspect of their experience, and the cure lies in skilled counselling which will enable the individual to adjust to his/her situation in a more appropriate way. That begs the question of whether the individual ought to be adjusted to fit the situation, or whether it is the situation that actually needs changing; and whether what we see going on in the individual is simply a normal, natural reaction to a situation that needs putting right.”[i]

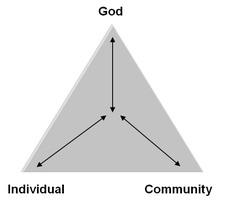

In order to understand further the nature and causes of this apparent polarisation between the disciplines, let us examine what I have chosen to refer to as the dynamic relational context in which every individual finds him or herself (Figure 1).

It would probably be helpful for me to define broadly, from the outset, what I mean by these terms in order to avoid possible confusion. Allow me to do this by introducing ‘Jane’. Jane is a single parent living in a one-bedroom, high-rise flat with her two young children. The Local Authority moved her into the flat two years ago but, as her children have been frequently sick, she has had little opportunity to get out and meet new people.

The flat is damp and, in spite of her requests to have the necessary repairs carried out, the Local Authority has taken no action. Over the past few months, Jane has been feeling increasingly depressed and, at times, violent towards her children. How to you, as Christian community worker or counsellor, respond to this situation?

It seems to me that a similar process is likely to take place in both disciplines; that is, to help the client/group (a) explore the experience, (b) develop and understanding of the experience and (c) take appropriate action. The difference between the Christian counsellor and community worker is likely to be that the counsellor attempts to help Jane to handle the situation and to grow in Christ-likeness through it whereas the community worker attempts to help Jane, along with others in the community facing similar difficulties, to change the situation itself.

Note that both are looking for change in and for Jane; the difference is the individual ~ situational focus. This is clearly an over-generalisation but it may, nevertheless, serve to highlight similarity in methodology alongside a difference in emphasis. This counselling/community work relationship does, however, have its tensions; expressed well by Alan Billings in an article on tackling stress:

“I notice in my (theological college)…if we lay on courses in counselling or therapy, they are always oversubscribed. If you put on a programme that’s about community work skills or what’s happening in our towns or cities…nobody wants to come; but they do want to learn about counselling skills.

“Here is a sick person coming into a healing service, who is going to be prayed for and hands laid on and they are going to be healed, and they will go back home to unemployment, the slum building they are living in, to the one-parent family situation, and so on. It’s that kind of thinking, and the whole way of approach, that I really want to attack and say, “This won’t do.” This is really quite inadequate and its not the answer to our problems.

“My students at the college see stress as the inability of individuals to come to terms psychologically with some or other aspect of their experience, and the cure lies in skilled counselling which will enable the individual to adjust to his/her situation in a more appropriate way. That begs the question of whether the individual ought to be adjusted to fit the situation, or whether it is the situation that actually needs changing; and whether what we see going on in the individual is simply a normal, natural reaction to a situation that needs putting right.”[i]

In order to understand further the nature and causes of this apparent polarisation between the disciplines, let us examine what I have chosen to refer to as the dynamic relational context in which every individual finds him or herself (Figure 1).

Figure 1

You will notice that no person exists in isolation; that is, every person exists in relation to God (although the nature of that relationship may be open to question) and in relation to others, e.g. family, friends, work colleagues etc.

In a Christian worldview, it is important to note that not only does each party within the triangle have impact on the others but also that each party is impacted by the others. ‘No man is an island…’ The Biblical concept of covenant community (OT Israel; NT church) provides a paradigm for the inter-relationship between personal, spiritual and corporate (e.g. 1 Jn 4:20).

For example, God’s relationship with individuals affects their relationships with others; God’s relationship with communities affects individuals within those communities; an individual’s relationship with others affects his/her relationship with God etc. This principle is, in fact, extended to include relationships with others beyond the covenant community; e.g. Exodus 22:21, Galatians 6:10.

“We ought, therefore, to say that pastoral care is situational and neglects its context at its peril.”[ii] Jane may feel alone, but her response to her situation, whatever that may be, will ultimately have its effect on those around her.

Secularisation (among other influences) has, on the other hand, produced a contradictory worldview in which the individual is of paramount importance and in which his/her relational triangle has been largely dismantled and compartmentalised. This would appear to be a distinctively modern (and mainly Western) phenomenon in which the concept of ‘community’ has been reduced to little more than that of a group of autonomous individuals within the same geographical locality.

Counselling and therapy (e.g. Freud/Rogers) have been criticised for not only reflecting but actually reinforcing this worldview through their emphasis on individual growth and development within what appears to be a social/spiritual vacuum. It is true that some approaches to counselling (e.g. CWR) do require that individuals work through their relationship with God and other key individuals with whom they are in direct contact (cf family therapy) but counselling in general has largely ignored the broader social context within which counselees find themselves, not only as ‘victims’ but also as participants (by default or otherwise).

Evangelicals, in particular, have been criticised for our implicitly ‘reactionary’ tendencies and for pursuing a philosophy of care – “the opium of the people” – which preserves the status quo by helping people to live with the social conditions in which they find themselves rather than harnessing their feelings to change those conditions. In other words, it is very likely that Jane’s counsellor would help her individually to work and grow through her situation; it is highly unlikely that she would be encouraged to take what could amount to social/political action to change that situation.

There is insufficient space in this article to pursue the many factors that underlie this issue, but perhaps it is necessary to question how, as counsellors, we can effect change in the lives of individuals without inadvertently undermining the impetus for long-term social change (cf Isaiah 58:6-12).

On the other hand, community work has been criticised for focusing so strongly on corporate community needs that individual needs have been ignored or neglected. It has also been criticised for sometimes assuming the thesis, based on what may be regarded as an over-optimistic view of human nature, that individual change will occur naturally as a result of changes in social conditions. It is perhaps this objection more than any which may account for why so few evangelicals, with our emphasis on original sin and salvation of the individual, are actively involved in the community work field.

Having said that, let us not forget that social change can create the conditions under which individual change is more able to take place, even if the latter does not follow necessarily from the former. Jane’s feelings could be very different, for instance, if she were living in a pleasant, suburban housing estate. Let us also remember that community work aims to work with people, in their struggle for change, in such a way that appropriate Biblical methods are employed and that individuals grow in Christ-likeness through their collective involvement in the process.

In view of the respective strengths and weaknesses of both counselling and community work, therefore, it would seem to be the case that the most effective change in the lives of individuals and communities can best be achieved through closer cooperation between the disciplines. Indeed, the concerns and skills of counselling and community work are far from mutually exclusive. We are called to extend the Kingdom of God at both individual and corporate levels and the realm of the activity of the Spirit is restricted neither to the counselling room nor to the estate office.

Perhaps a first step in this process is an increase in dialogue between practitioners in the field. It is my hope that this article will serve to highlight some of the issues involved in order to make this step possible.

Footnotes

[i] Billings, A (1990). Tackling Stress – Social and Political Factors in Ballard, P (Ed). Issues in Church-Related Community Work. University of Wales College of Cardiff. p90f.

[ii] Wilson, M (1985). Personal Care & Political Action. Contact. Issue 2. 1985. p14.

You will notice that no person exists in isolation; that is, every person exists in relation to God (although the nature of that relationship may be open to question) and in relation to others, e.g. family, friends, work colleagues etc.

In a Christian worldview, it is important to note that not only does each party within the triangle have impact on the others but also that each party is impacted by the others. ‘No man is an island…’ The Biblical concept of covenant community (OT Israel; NT church) provides a paradigm for the inter-relationship between personal, spiritual and corporate (e.g. 1 Jn 4:20).

For example, God’s relationship with individuals affects their relationships with others; God’s relationship with communities affects individuals within those communities; an individual’s relationship with others affects his/her relationship with God etc. This principle is, in fact, extended to include relationships with others beyond the covenant community; e.g. Exodus 22:21, Galatians 6:10.

“We ought, therefore, to say that pastoral care is situational and neglects its context at its peril.”[ii] Jane may feel alone, but her response to her situation, whatever that may be, will ultimately have its effect on those around her.

Secularisation (among other influences) has, on the other hand, produced a contradictory worldview in which the individual is of paramount importance and in which his/her relational triangle has been largely dismantled and compartmentalised. This would appear to be a distinctively modern (and mainly Western) phenomenon in which the concept of ‘community’ has been reduced to little more than that of a group of autonomous individuals within the same geographical locality.

Counselling and therapy (e.g. Freud/Rogers) have been criticised for not only reflecting but actually reinforcing this worldview through their emphasis on individual growth and development within what appears to be a social/spiritual vacuum. It is true that some approaches to counselling (e.g. CWR) do require that individuals work through their relationship with God and other key individuals with whom they are in direct contact (cf family therapy) but counselling in general has largely ignored the broader social context within which counselees find themselves, not only as ‘victims’ but also as participants (by default or otherwise).

Evangelicals, in particular, have been criticised for our implicitly ‘reactionary’ tendencies and for pursuing a philosophy of care – “the opium of the people” – which preserves the status quo by helping people to live with the social conditions in which they find themselves rather than harnessing their feelings to change those conditions. In other words, it is very likely that Jane’s counsellor would help her individually to work and grow through her situation; it is highly unlikely that she would be encouraged to take what could amount to social/political action to change that situation.

There is insufficient space in this article to pursue the many factors that underlie this issue, but perhaps it is necessary to question how, as counsellors, we can effect change in the lives of individuals without inadvertently undermining the impetus for long-term social change (cf Isaiah 58:6-12).

On the other hand, community work has been criticised for focusing so strongly on corporate community needs that individual needs have been ignored or neglected. It has also been criticised for sometimes assuming the thesis, based on what may be regarded as an over-optimistic view of human nature, that individual change will occur naturally as a result of changes in social conditions. It is perhaps this objection more than any which may account for why so few evangelicals, with our emphasis on original sin and salvation of the individual, are actively involved in the community work field.

Having said that, let us not forget that social change can create the conditions under which individual change is more able to take place, even if the latter does not follow necessarily from the former. Jane’s feelings could be very different, for instance, if she were living in a pleasant, suburban housing estate. Let us also remember that community work aims to work with people, in their struggle for change, in such a way that appropriate Biblical methods are employed and that individuals grow in Christ-likeness through their collective involvement in the process.

In view of the respective strengths and weaknesses of both counselling and community work, therefore, it would seem to be the case that the most effective change in the lives of individuals and communities can best be achieved through closer cooperation between the disciplines. Indeed, the concerns and skills of counselling and community work are far from mutually exclusive. We are called to extend the Kingdom of God at both individual and corporate levels and the realm of the activity of the Spirit is restricted neither to the counselling room nor to the estate office.

Perhaps a first step in this process is an increase in dialogue between practitioners in the field. It is my hope that this article will serve to highlight some of the issues involved in order to make this step possible.

Footnotes

[i] Billings, A (1990). Tackling Stress – Social and Political Factors in Ballard, P (Ed). Issues in Church-Related Community Work. University of Wales College of Cardiff. p90f.

[ii] Wilson, M (1985). Personal Care & Political Action. Contact. Issue 2. 1985. p14.