Walk with me

Wright, N. (2003) ‘Walk with Me: Mentoring & Discipleship in Social Work’, The Extra Mile, Social Workers’ Christian Fellowship, Autumn, No22, pp15-21.

Abstract

The popularity of mentoring in social work has grown markedly in recent years, providing an effective development mechanism for both practitioners and clients. Nevertheless, confusion abounds in terms of what mentoring is and what it should look like in practice. This article demonstrates that the Bible itself provides examples of mentoring relationships in the context of discipleship that can help inform Christian good practice. A mentoring model is introduced that provides a basic conceptual framework and tips are provided on managing the mentoring relationship effectively. The article includes throughout case examples and follow-up resources for those with a special interest in this field.

Concept

Mentoring receives tremendous acclaim in people-development and social work circles today, rivalled only, perhaps, by action learning in terms of its dramatic rise in popularity. You could be mistaken for thinking that something brand new has been discovered. In fact, the term 'mentoring' dates back to Greek mythology where Mentor, trusted friend of Ulysses, oversees the care and direction of Ulysses’ son, Telemachus. This concept has been preserved through time in the image of a skilled master craftsman providing role modelling and personal training for an inexperienced apprentice or protégé.

Given this richness of history, you might expect that someone by now would have come up with the definitive answer on what mentoring is and what is should look like in practice. Research in this field, however, suggests that there are now probably as many definitions are there are mentors.[i] In light of this, and in order to avoid being sucked down some deep semantic plughole, I'll describe mentoring in my own terms and hope that what I write will resonate with some of your own ideas and experiences too.

The underlying notion of an experienced person providing developmental support to the less-experienced is the one strand that most mentoring models do hold in common. Interestingly, this reflects various foundational concepts in social, community and youth work practice. In principle at least, mentoring for development will feel very familiar to people working in these fields. One of my own colleagues, Jonathan, spent a number of years working with young people at risk of exclusion, helping them to identify possibilities, aspirations, barriers and how to overcome them. Only recently has he realised that he might benefit from input of this kind, too.

Parallels in mentoring with Judeo-Christian models of discipleship are readily recognisable, with accounts of, for example, Moses~Joshua, Elijah~Elisha and Paul~Timothy springing to mind. The model that Jesus provides is an ideal for Christians and corresponds, in many respects, with current secular models. One contrast is that Jesus chose his own protégés (Jn 15:16) whereas the reverse dynamic or matching by a 3rd party (e.g. Learning & Development) is likely to be true today. The implications of ‘who-chooses-who’ in the mentoring relationship will be explored in further depth below.

Releasing potential

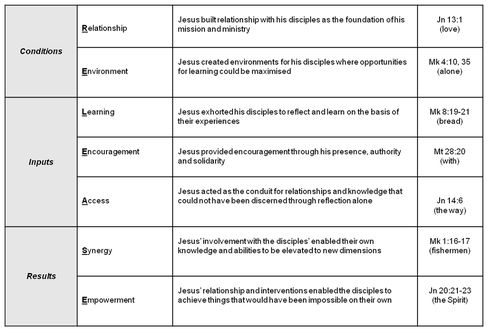

I have found it helpful to conceive of a Christian approach to mentoring in terms of a ‘RELEASE model’, drawing attention to 7 principal characteristics that fall naturally into 3 separate categories:

Abstract

The popularity of mentoring in social work has grown markedly in recent years, providing an effective development mechanism for both practitioners and clients. Nevertheless, confusion abounds in terms of what mentoring is and what it should look like in practice. This article demonstrates that the Bible itself provides examples of mentoring relationships in the context of discipleship that can help inform Christian good practice. A mentoring model is introduced that provides a basic conceptual framework and tips are provided on managing the mentoring relationship effectively. The article includes throughout case examples and follow-up resources for those with a special interest in this field.

Concept

Mentoring receives tremendous acclaim in people-development and social work circles today, rivalled only, perhaps, by action learning in terms of its dramatic rise in popularity. You could be mistaken for thinking that something brand new has been discovered. In fact, the term 'mentoring' dates back to Greek mythology where Mentor, trusted friend of Ulysses, oversees the care and direction of Ulysses’ son, Telemachus. This concept has been preserved through time in the image of a skilled master craftsman providing role modelling and personal training for an inexperienced apprentice or protégé.

Given this richness of history, you might expect that someone by now would have come up with the definitive answer on what mentoring is and what is should look like in practice. Research in this field, however, suggests that there are now probably as many definitions are there are mentors.[i] In light of this, and in order to avoid being sucked down some deep semantic plughole, I'll describe mentoring in my own terms and hope that what I write will resonate with some of your own ideas and experiences too.

The underlying notion of an experienced person providing developmental support to the less-experienced is the one strand that most mentoring models do hold in common. Interestingly, this reflects various foundational concepts in social, community and youth work practice. In principle at least, mentoring for development will feel very familiar to people working in these fields. One of my own colleagues, Jonathan, spent a number of years working with young people at risk of exclusion, helping them to identify possibilities, aspirations, barriers and how to overcome them. Only recently has he realised that he might benefit from input of this kind, too.

Parallels in mentoring with Judeo-Christian models of discipleship are readily recognisable, with accounts of, for example, Moses~Joshua, Elijah~Elisha and Paul~Timothy springing to mind. The model that Jesus provides is an ideal for Christians and corresponds, in many respects, with current secular models. One contrast is that Jesus chose his own protégés (Jn 15:16) whereas the reverse dynamic or matching by a 3rd party (e.g. Learning & Development) is likely to be true today. The implications of ‘who-chooses-who’ in the mentoring relationship will be explored in further depth below.

Releasing potential

I have found it helpful to conceive of a Christian approach to mentoring in terms of a ‘RELEASE model’, drawing attention to 7 principal characteristics that fall naturally into 3 separate categories:

Each of the features depicted in this model can be applied directly and/or by analogy to mentoring in various dimensions of social work. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this article, I will concentrate on provision of mentoring for social workers rather than, say, by social workers for other workers, volunteers or clients.

Relationship

The centrality of relationship in the model presents a strong case for self-selection in the establishing of mentoring relationships. If mentor and social worker don’t feel sufficiently comfortable working together, the relationship is likely to be limited in effectiveness, counterproductive or simply avoided. Social workers may, however, benefit from mentoring support from people in different parts of the department/organisation with whom they would not ordinarily have awareness or contact (see Access below).

One way to tackle this difficulty, whilst maintaining a self-selecting component, is to arrange informal meetings between potential mentor/social work candidates to explore possibilities without formal commitment. This kind of encounter, analogous perhaps to ‘speed-dating’ in other contexts(!), is best mediated by a 3rd party, e.g. Learning & Development, which can provide guidance, advice on follow-up and trouble-shooting if things go wrong.

Conversely, if mentor and social worker are too familiar, they may avoid honesty in order to preserve friendship or collude where challenge would be more appropriate. The tensions here can, of course, mirror those inherent to the social worker-client relationship, the latter of which may actually reproduce itself in the mentoring relationship itself[ii]. Wisdom, insight and awareness are essential, therefore, in selecting and maintaining the right relationship.[iii]

Environment

Mix flour, water and yeast together and you won’t get a soft and crusty loaf of bread unless you provide warmth for the dough and heat for baking in the oven. It’s a careful combination of ingredients and environment that makes the difference. The same is true, by analogy, for the mentoring relationship too. Provide all the right inputs but if there’s no environment to support learning and development, mentoring can be a frustrating and ineffective experience.

Suzanna received mentoring support from a senior manager in another department. She felt inspired and returned to work after each meeting brimming with ideas. Suzanna’s own line-manager, however, felt threatened by her work with the mentor (“What if her bright ideas put me in a bad light with the rest of the team?”) and about her relationship with the mentor itself (“What if they are using their time to criticise me?”). After just 3 months, the line-manager called a halt to the mentoring arrangement.

In light of this, I advise that key stakeholders (e.g. including the protégé’s line-manager) are involved in planning the mentoring arrangements from the outset so that any concerns can be aired before moving forward. Periodic review with the various parties involved and facilitated by an appropriate 3rd party can also help to ensure that things stay on track.

Learning

The learning dimension of this model could be described as a ‘pooling of knowledge for the benefit of the protégé’. In this respect, mentoring is less concerned with non-directiveness than its coaching and supervision counterparts which tend to focus more on facilitation and reflective practice.[iv] Learning in the mentoring relationship takes place when the protégé has opportunity to learn from the distilled experience and wisdom of the mentor. In this respect, the mentor is sometimes equated with a ‘personal tutor’, although the learning process in mentoring tends to be more interactive than didactic in nature.

A risk in mentoring, as in coaching and supervision, is that the mentor may inappropriately impose his or her own agendas and perspectives onto the protégé, hence moving to ‘instructor’ mode. In order to avoid this dynamic, it is important that the protégé learns to (a) determine the agenda at the start of each meeting and (b) specify explicitly what kind of input that he/she desires. It is also helpful to set aside time at the end of each meeting to review process and content together (e.g. “What worked well in terms of how we worked today?”).

Encouragement

According to certain schools of psychoanalytic thought, anxiety is a chronic condition that may well account for much human motivation and behaviour. Fear of rejection, failure and annihilation are common examples that surface in therapeutic practice. In light of this, I find it very significant that the Bible commits so much space to encouragement as a Divine antidote to human anxiety (e.g. Josh 1:5-9: courage; Heb 13:5f: never leave). Whereas fear crushes and debilitates, encouragement inspires and liberates. Significantly, God provides encouragement by words and presence: “I will be with you.”

Janet had been in social work for 15 years and was known among colleagues as a person of tremendous insight and experience. Nevertheless, Janet lacked personal and professional confidence and found herself avoiding opportunities for promotion even when they would have been beneficial for both her and the team. By meeting with a senior social worker in mentoring role once a month for a year, Janet learned more about the realities of such roles and how to address the types of situation that evoked anxiety within her. She also found strength through relationship with a significant other committed to her well-being. “Being with”, she commented in retrospect, “was really the most important part of the mentoring relationship for me.”

In this instance, the mentor’s on-going empathy and encouragement enabled Janet to gain sufficient confidence to apply for a more senior post. Three years later, Janet was appointed as team leader.

Access

Mentoring provides ideal opportunity for protégés to gain access to new information, experiences and relationships that may be, in practice, highly improbable within the constraints of ordinary work/roles. Because of this, mentoring schemes are often used as vehicles for career development, enabling potential ‘high flyers’ and/or under-represented groups (e.g. ethnic minorities, women, people with disabilities) to gain knowledge, visibility and capabilities that will help prepare them for promotion to senior roles.

Examples of ways in which mentors can provide access of this nature could include allowing protégés to shadow them on project tasks or accompany them to meetings where they will meet other senior colleagues. Provide them with ‘privileged’ access to networks and resources can be helpful too. We are reminded, in parallel, of Christ’s special disclosures to the inner circle of his disciples (e.g. Lk 8:10: parables).

Owing to real potential for unfair discrimination in this respect, however, it is important when formal mentoring schemes are introduced into an organisation that entry criteria to the scheme do not discriminate unfairly, directly or indirectly, and that they are applied consistently. If in doubt, consult the organisation’s HR specialists who should be able to offer advice in this area.

Synergy

Synergy is the combined energy of two or more sources. When synergy occurs, the output typically exceeds the sum of the individual sources. The mentoring relationship provides opportunity for the knowledge, experience, capabilities and creative energy of both mentor and protégé to synergise for the benefit of the protégé. Interestingly, mentors often report that engaging in a role of this kind provides them with refreshed energy and insight, too.

Daniel agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to provide mentoring support for a junior colleague, Gary, who had just joined the team after completing his social work studies. The thought of taking on additional responsibilities left Daniel feeling very concerned about additional drain on his already depleted time resources. Six months into the relationship, however, Daniel reported with surprise that the issues and questions posed by Gary had challenged him to review his own values and practice too: “I haven’t felt like this for years. Gary’s enthusiasm over his work has rekindled a passion within me that I thought I’d lost completely.”

In light of this dynamic, once again it is important to underline at the start of the mentoring relationship that the principal focus should be on that of the development of the protégé, albeit with benefits for the mentor too as a potential by-product.

Empowerment

Empowerment is concerned at heart with enabling, helping make possible options and opportunities that may never arise without 3rd party intervention. As we have seen above, the various facets of mentoring combined can provide a significant developmental resource for the protégé. Mentoring can provide a valuable mechanism for wider organisation development, too, stimulating renewed enthusiasm/expertise for those acting as mentors and enabling the organisation to develop cross-departmental relationships and capacity.

Summary

We have noted that the popularity of mentoring in social work has grown markedly in recent years, providing an effective development mechanism for both practitioners and clients. Nevertheless, a degree of confusion persists in terms of what mentoring is and what it should look like in practice.

The Bible itself provides examples of mentoring relationships in the context of discipleship that can help inform Christian good practice. Paradigm’s ‘RELEASE’ model, based on aspects of Jesus’ own approach, provides a basic conceptual framework and can be applied/adapted to various dimensions of social work. The model draws attention to the centrality of relationship, the importance of a wider learning environment, key inputs to support development and potential benefits for protégé, mentor and organisation.

Dynamics have been identified and tips provided on managing the mentoring relationship effectively. I hope these have been helpful but will be happy to be contacted by readers of The Extra Mile with queries, additions or alternative perspectives.

Footnotes

[i] For a comprehensive survey, see Roberts, A (2000): Mentoring Revisited: A Phenomenological Reading of the Literature. Mentoring & Tutoring Journal. Vol 8. No 2. p145-168.

[ii] See ‘parallel process’ in Hawkins, P & Shohet, R (2000): Supervision in the Helping Professions. p80-82.

[iii] For additional ideas and advice, see Clutterbuck, D (1992): Everyone Needs a Mentor.

[iv] See Martyn, H (2000): Developing Reflective Practice – Making Sense of Social Work in a World of Change.