|

‘Coincidence doesn't happen a third time.’ (Osamu Tezuka) I arrived in the Netherlands on Saturday, aiming to orientate myself briefly to this new country before working with an INGO team there on Monday. When I stepped into my hotel room, however, it smelt damp and sweaty. Trying not to breathe, I opened the windows to an icy blast and decided to go for a walk while the fresh air did its work. Not far away, I noticed a church building so walked over to have a glance at its meeting times. As I did so, I looked up and saw a cross in the sky, a misty symbol painted momentarily on blue canvas by vapour trails. It felt significant, but I didn’t know why. The next day, the church was full when I arrived and I sat quietly in the midst, happily surprised by how much Dutch I could understand. (I can speak German, but this was my first time to read this new language). At the end, a woman kindly introduced herself to me. On learning that I am English, she explained that the church is recovering from an intensely painful internal conflict. The pastor had spoken on a need to look to God. I showed her the photo I had taken the day before – a symbol of suffering and hope – and she started to weep. ‘God brought you here to us this morning, Nick.’ Another woman now introduced herself, explained briefly that she had worked internationally in medical mission, and invited me to a special meeting that afternoon for asylum seekers and refugees. ‘How could she possibly have known anything about my life and work?’ I asked myself, a total stranger. The guest speaker that day was a visitor from Algeria and, serendipitously, works for the same organisation I was about to work with the following day... as does a man who randomly found himself sitting beside me in a hall full of people. Was this all coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide.

16 Comments

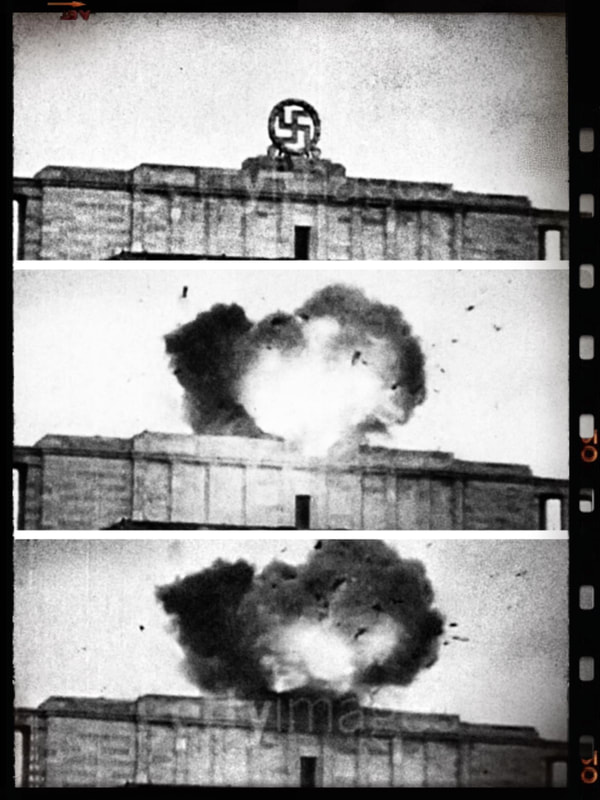

Few images have more powerful emotional resonance for me than that moment at which the WW2 Allies detonated explosives under a huge marble swastika at the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nürnberg, Germany. It was the place where, just before the war, Hitler and his followers had held their infamous Nazi rallies. The rallies had proved a potent propaganda weapon, convincing Nazi supporters of their own ‘supremacy’ and intimidating their enemies into fearful submission. The public destruction of this infamous symbol marked the impending final demise of the deranged Nazi myth and its psychopathic regime, and the end of by far one of the worst eras in human history. I can only imagine how it must have felt for those who had suffered so terribly to witness, at last, this emerging glimmer of hope. Similar evocative and symbolic moments were soon to follow with a Soviet flag over the German Reichstag and an American flag raised on Iwo Jima. There’s something about these images-as-symbols that capture and express a wider human story and experience. They carry and convey powerful psychological, cultural and emotional meaning for those who understand and identify with what they represent. Other well-known examples of symbols include the Christian cross as a sign of God’s love and salvation through Jesus Christ or, conversely, ominous ‘Z’ insignia on Russian military vehicles during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. What symbols have a particular resonance for you – and why? ‘Question: Why do scuba divers always fall backwards out of the boat? Answer: Because if they fell forwards, they’d still be in the boat.’ (That meme still makes me smile). It takes me back to a recent conversation with an action learning group. We were practising a Gestalt technique of noticing use of metaphors as a person speaks, then inviting playful exploration to see what fresh insights and ideas might emerge. It has some parallels with James Lawley & Penny Tompkins’ symbolic modelling (Metaphors in Mind, 2000). Whilst thinking through an issue she was struggling with at work, one participant explained that she felt worried about ‘rocking the boat’. Picking up on the metaphor and stretching it towards a greater polarity, a peer asked, ‘How would it be if you were to sink the boat?’ Then, after she had had time to reflect and respond, another posed, ‘In that situation, what would it take to float your boat?’ In a Gestalt coaching context, I might invite the same person to enact the different metaphorical possibilities physically. We could use objects such as tables and chairs in the room to represent the boat and other significant people or situational factors, then experiment with rocking, sinking, floating or navigating through them. Doing it is very different to imagining it or talking about it. What experience do you have of working with metaphor? How do you do it? I ran a coach training course this week and, during a practise session, one of the participants drew coloured symbols on post-its as an aide memoire. They were familiar symbols – the kind you might see on a CD or DVD player: rewind, play, pause, fastforward, stop:

*Rewind: e.g. ‘Let’s remind ourselves of the outcome you’d like to work towards. What stands out to you now as most important in this?’ *Play: e.g. ‘Say more..? How would it be if you were to draw that? How are you feeling now as you talk about this?’ *Pause: e.g. ‘Let’s just pause for a moment. Where are we now? What do we need to do next?’ *Fastforward: e.g. ‘OK…moving forward…what will your next step be?’ *Stop: e.g. ‘Is there anything else we need to do today? Are we finished?’ They also drew a cup of hot tea as a useful reminder that, sometimes, it’s good to step back from the issue, have a break and return to it with fresh energy if needed. I loved the idea of using these visual symbols as simple prompts. What prompts have you found useful? How would you describe your coaching style? What questions would you bring to a client situation?

In my experience, it depends on a whole range of factors including the client, the relationship, the situation and what beliefs and expertise I, as coach, may hold. It also depends on what frame of reference or approach I and the client believe could be most beneficial. Some coaches are committed to a specific theory, philosophy or approach. Others are more fluid or eclectic. Take, for instance, a leader in a Christian organisation struggling with issues in her team. The coach could help the leader explore and address the situation drawing on any number of perspectives or methods. Although not mutually exclusive, each has its own focus and emphasis. The content and boundaries will reflect what the client and coach believe may be significant: Appreciative/solutions-focused: e.g. ‘What would an ideal team look and feel like for you?’, ‘When has this team been at its best?’, ‘What made the greatest positive difference at the time?’, ‘What opportunity does this situation represent?’, ‘On a scale of 1-10, how well is this team meeting your and other team members’ expectations?’, ‘What would it take to move it up a notch?’ Psychodynamic/cognitive-behavioural: e.g. ‘What picture comes to mind when you imagine the team?’, ‘What might a detached observer notice about the team?’, ‘How does this struggle feel for you?’, ‘When have you felt like that in the past?’, ‘What do you do when you feel that way?’, ‘What could your own behaviour be evoking in the team?’, ‘What could you do differently?’ Gestalt/systemic: e.g. ‘What is holding your attention in this situation?’ ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What are you inferring from people’s behaviour in the team?’, ‘What underlying needs are team members trying to fulfil by behaving this way?’, ‘What is this team situation telling you about wider issues in the organization?’, ‘What resources could you draw on to support you?’ Spiritual/existential: e.g. ‘How is this situation affecting your sense of calling as a leader?’, ‘What has God taught you in the past that could help you deal with this situation?’, ‘What resonances do you see between your leadership struggle and that experienced by people in the Bible?’, ‘What ways of dealing with this would feel most congruent with your beliefs and values?’ An important principle I’ve learned is to explore options and to contract with the client. ‘These are some of the ways in which we could approach this issue. What might work best for you?’ This enables the client to retain appropriate choice and control whilst, at the same time, introduces possibilities, opportunities and potential new experiences that could prove transformational. ‘What is most important about any event is not what happened, but what it means. Events and meanings are loosely coupled: the same events can have very different meanings for different people because of differences in the schema that they use to interpret their experience.’ These illuminating words from Bolman & Deal in Reframing Organisations (1991) have stayed with me throughout my coaching and OD practice.

They have strong resonances with similar insights in rational emotive therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. According to Ellis, what we feel in any specific situation or experience is governed (or at least influenced) by what significance we attribute to that situation or experience. One person could lose their job and feel a sense of release to do something new, another could face the same circumstances and feel distraught because of its financial implications. What significance we attribute to a situation or experience and how we may feel and act in response to it depends partly on our own personal preferences, beliefs, perspective and conscious or subconscious conclusions drawn from our previous experiences. It also depends on our cultural context and background, i.e. how we have learned to interpret and respond to situations as part of a wider cultural group with its own history, values, norms and expectations. A challenge and opportunity in coaching and OD is sometimes to help a client (whether individual or group) step back from an immediate experience and reflect on what the client (or others) are noticing and not noticing, what significance the client (or others) are attributing to it and how this is affecting emotional state, engagement, choices and behaviour. Exploring in this way can open the client to reframing, feeling differently and making positive choices. In his book, Into the Silent Land (2006), Laird makes similar observations. Although speaking about distractions in prayer and the challenges of learning stillness and silence, his illustrations provide great examples of how the conversations we hold in our heads and the significance we attribute to events often impact on us more than events themselves. He articulates this phenomenon so vividly that I will quote him directly below: ‘We are trying to sit in silence…and the people next door start blasting their music. Our mind is so heavy with its own noise that we actually hear very little of the music. We are mainly caught up on a reactive commentary: ‘Why do they have to have it so loud!’ ‘I’m going to phone the police!’ ‘I’m going to sue them!’ And along with this comes a whole string of emotional commentary, crackling irritation, and spasms of resolve to give them a piece of your mind when you next see them. The music was simply blasting, but we added a string of commentary to it. And we are completely caught up in this, unaware that we are doing much more than just hearing music. ‘Or we are sitting in prayer and someone whom we don’t especially like or perhaps fear enters the room. Immediately, we become embroiled with the object of fear, avoiding the fear itself, and we begin to strategise: perhaps an inconspicuous departure or protective act of aggression or perhaps a charm offensive, whereby we can control the situation by ingratiating ourselves with the enemy. The varieties of posturing are endless, but the point is that we are so wrapped up in our reaction, with all its commentary, that we hardly notice what is happening, although we feel the bondage.’ This type of emotional response can cloud a client’s thinking (cf ‘kicking up the dust’) and result in cognitive distortions, that is ways of perceiving a situation that are very different (e.g. more blinkered or extreme) than those of a more detached observer. In such situations, I may seek to help reduce the client’s emotional arousal (e.g. through catharsis, distraction or relaxation) so that he or she is able to think and see more clearly again. I may also help the client reflect on the narrative he or she is using to describe the situation (e.g. key words, loaded phrases, implied assumptions, underlying values). This can enable the client to be and act with greater awareness or to experiment with alternative interpretations and behaviours that could be more open and constructive. Finally, there are wider implications that stretch beyond work with individual clients. Those leading groups and organisations must pay special attention to the symbolic or representational significance that actions, events and experiences may hold, especially for those from different cultural backgrounds (whether social or professional) or who may have been through similar perceived experiences in the past. If in doubt, it’s wise ask others how they feel about a change, what it would signify for them and what they believe would be the best way forward. Imagine over 2 billion people. It’s enough to make me feel dizzy, roughly a third of the world’s total population, Christians all over the globe marking a very significant event this weekend. Easter. But what does Easter mean for Christians? Why is it so important? How is it different to a colourful, pagan, fertility festival marked by chocolate, rabbits and eggs?

At the heart of the Christian Easter is a cross, a symbol used by Christians to highlight the centre-point of their faith. The cross is a reminder of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, crucified on a cross 2,000 years ago. It’s a shocking symbol, an instrument of Roman torture and agonising death. It draws our attention to a God-man-saviour, prepared to give his life for us. That’s where it gets hard. What if the biblical account is true? Can I dare myself to believe it? What if Jesus really was the Son of God? Could he really love someone as messed up as me? I can only draw one conclusion. If this story is true, the cross cries out in the starkest possible terms that no matter who we are or what we have done, we really matter to God. And there is more hope. Easter Sunday marks an equally remarkable event. This Jesus who died is raised by God. Miraculously, he is brought back to life and, what is more, promises us life over death by trusting in him. He offers us light, life and hope in the midst and beyond the dark deaths and despair we may face in life, psychological, emotional and physical. So that’s where I place my faith. Not in my weak and inconsistent efforts to be a good person, a clever person, an interesting or adventurous person. I know what I’m really like inside. Amazingly, God is never disillusioned with me because he never had any illusions in the first place. I place my faith in Jesus. If the Bible is true, he truly deserves my life. Who or what has most influenced your OD thinking and practice? What maxims or principles do you bear in mind as you approach organisational issues from an OD perspective? Someone asked me this question recently and I crystallised my response into seven statements, drawing on background influences including Morgan, Schein, Bolman & Deal, Gergen and Burr:

*Organisations do not exist but people do. *Every action is an intervention. *Actions have symbolic as well as rational meaning. *What’s important is not what happens, but what it means. *The same event has different meanings for different people. *People get trapped in their own psychological and cultural constructs. *What passes for rationality is often irrationality in disguise. These statements, taken as a whole, create a metaphorical lens through which I often view, analyse or interpret a situation or experience. They help me to consider an underlying question, ‘What is really going on here?’ before attempting to work with a client or organisation to devise a way forward. What maxims or principles do you use to guide your practice? I have a dream, a crazy drama played out in the subconscious which seems to make sense at the time but leaves me with a strange feeling, a feeling of loss, even as the images fade away. The drama was based loosely on something I had experienced a long time ago, virtually forgotten about, and yet reappeared with fresh dynamism and vividness. What’s that all about?

Some dream therapists try to analyse the images, at least the dreamer’s recollection of them, to explore and interpret what they could represent in the real world. It’s a tricky business, especially as it’s often hard to retain a clear memory of them. It assumes a symbolic significance to the dream and the images within it, a rare opportunity to explore the hidden unconscious. I’m not sure. It strikes me that one significant aspect is the feeling, what a person experiences emotionally in the dream. Is it possible that the feeling points to something the dreamer is experiencing in the conscious present but that lies out of awareness? What is the loss I’m experiencing now, the loss that lies unacknowledged or that I’m not paying attention to? I’m really interested in this idea of representation. The dream example suggests that something we experience at face value within the dream could represent and reveal something else in reality. It’s a sign that points beyond itself. I think it could the same in waking experiences too. The challenging part is knowing how to distinguish representation from reality. So we meet this person. We talk, laugh, do stuff together. The person starts to feel like a friend, a lover, whatever he or she means to us. And we wonder what this person, this experience, this relationship, represents for us. Is it really the person per se, or something he or she evokes – an idea, an aspiration, an unfulfilled dream, a substitute for something we're missing elsewhere? I don’t know, perhaps it’s both. I can enjoy the new person, relationship, encounter, experience and I can inquire of myself what it may point to in other aspects of my life that lie unacknowledged or that I need to pay attention to. At times it can serve as a wake-up call, an opportunity for raised awareness, a chance to step back from the normal to examine things in a fresh light. It's about discernment. We risk projecting our hopes and expectations onto another, creating of them what we subconsciously need and yearn for rather than seeing them for who they really are. We risk projecting the same onto new experiences, a new job, a new home that prevent us experiencing them afresh for what they really are and for the potential they may hold. The opportunity is then to ask the right questions of myself, of new relationships, situations and experiences. ‘What is this person, this situation, this experience to me? Why this, why now? What feelings does it evoke for me? What does that mean, point to? What am I at risk of projecting onto another? What am I not noticing or paying attention to in other aspects of my life?’ And I think about my belief in God, my relationship with him. I think about the language he uses to communicate, a human language. I think about the many different analogies he uses to reveal himself. I’m aware of how I can confuse the representation with the reality, to naiively assume that God is confined to the limits of my own language, knowledge, experience and imagination. So, the challenge lies here. It’s about distinguishing the signpost, the symbol from the actual. It's about recognising that new encounters, relationships and experiences can carry meaning for us at multiple levels. It’s about trying our best to face reality with eyes wide open, open to see ourselves, people and situations, even God for who and what they truly are and can be. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed