|

‘Anyone can be a Father – but it takes someone special to be a Dad.’ (Wade Boggs) Father’s Day will feel very different this year. My Dad died recently and, no matter how old a person is when they pass away, to me he was still my Dad. That gave him a unique place in my life and a special relationship in my world of experience. To be honest, on reflection, I don’t think I ever knew my Dad that well. Yes, we shared lots of different times together over the years and I have all kinds of memories of him, but that’s not the same as…really…knowing…someone. He came from a generation that didn’t really disclose or expose deep feelings. As a child, I looked up to him as a strong, dependable figure in my life: someone I respected, sometimes from a relative relational distance. He was a motorbike fanatic and had a significant influence on my love for motorcycles and motorcycling, as he did on my brothers too. He was great at DIY – a talent that, sadly, I didn’t inherit from him – and could build or repair just about anything. I hadn’t really realised until we were preparing for his eulogy that I had never heard him once speak badly about anyone. He was a man of integrity and kept his silence. Two weeks before Dad died, I was called back urgently from Germany. He had had a fall, with complications, and the doctors didn’t expect him to survive. I raced to the hospital and, thank God, had time with him. He was vulnerable. I stayed overnight, tried my best to advocate for him and fed him gently when he could no longer feed himself. I plucked up the courage to tell him, for the first time, that I loved him. He told me, for the first time, that he loved me too. The day before he died, he whispered, ‘Thank you for everything you have done.’ I cried. I had never felt closer to him than in those precious, painful moments. A beautiful sadness. Dad – I will never forget you.

17 Comments

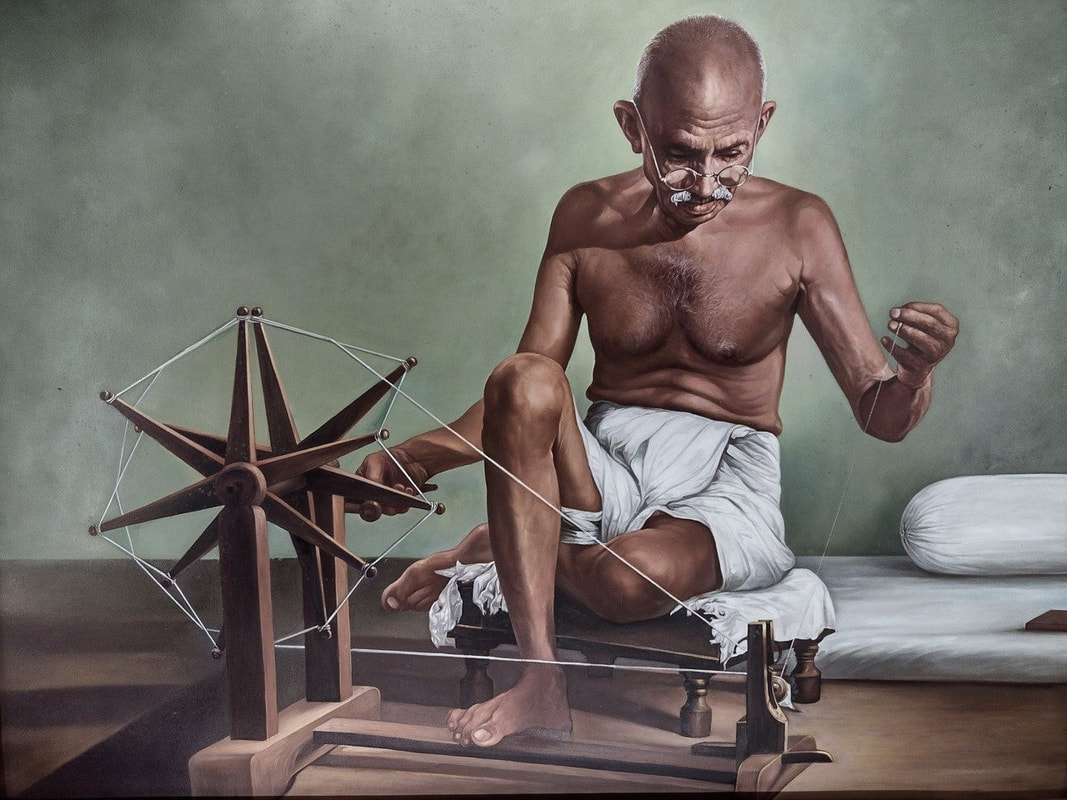

‘Well-behaved women rarely make history.’ (Laurel Thatcher Ulrich) International Women’s Day. A day to recognise and celebrate the extraordinary contribution of women all over this world and throughout all history. There are so many amazing women who have inspired, stretched and enriched my life: those I’ve known, those I’ve heard or read about and those I’ve only encountered indirectly through the personal-cultural legacy they’ve left behind. This is a shout-out, a thank you, to all women – especially to those who are and feel invisible and unseen; those who live on the frayed and torn edges of societies; those who persevere in the face of poverty, vulnerability and other threats; those who live and love in a way that goes unnoticed and unknown. You humble and challenge me. The world is a better place because you're here. ‘Always vote for principle, though you may vote alone.’ (John Quincy Adams) I never had the privilege of meeting Soji Taguchi, but I do wish I had. Soji was a manager at a Japanese-owned textiles factory in the Philippines. Seeing how meagrely the Filipino workers were paid, he gave away a significant portion of his own salary each month to top up theirs. When a young Filipina was severely distressed one day and, in her upset, damaged an expensive piece of machinery, he paid for the repairs himself. Instead of chastising her he listened to her plight and, subsequently, regularly slipped money (secretly) into her pockets to help her, a poor teenager, to pay her bills. This woman’s life is now a clear reflection of his. The power of a positive role-model. Ted Winship was my mentor, a shopfloor supervisor at an industrial site in the UK. Once, the workers refused to enter an enclosure because the conditions in it were so terrible. The manager told Ted that, if he could persuade them to do the work, they would all be paid a substantial bonus. Ted took the manager at his word. He entered the compound first and the work was completed on time. At the end of the project, however, the manager refused to pay the bonus and only gave Ted his. It was a serious breach of trust. On hearing of this betrayal, Ted confronted the manager but to no avail. He distributed his own bonus to the workers, resigned from his job and walked out. Ethics in action. Self-sacrifice for the sake of others. The personal costs were high – but the spiritual benefits were immeasurable. ‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life? You arrange to meet with a colleague and, on the afternoon of the appointment, she neither turns up nor cancels it. It can feel disappointing or frustrating, especially if you had spent ages preparing for it, or had rescheduled other things to make room for her in your diary. There may be, of course, all kinds of extenuating circumstances that had prevented her from arriving or letting you know. We could imagine, for instance, that her car had broken down on route, or that she had got stuck in traffic in an area with no mobile phone signal. She might have been held up in another meeting that overran and from which, for whatever reason, she had felt unable to excuse herself. Feelings of hurt or resentment can arise, however, if we allow ourselves to infer deeper meaning and significance from the no show. This can be especially so if it forms part of a wider and repeated pattern of experiences. Could it be, for instance, that her unexpected absence (again) is revealing a subtle and subliminal message such as, ‘Spending time on A is more important to me than spending time with you on B.’ Or, beneath that, ‘I believe my work on A is more important than your work on B’. Or deeper and worse still, perhaps, ‘I’m more important than you.’ The latter could well leave us feeling devalued and disrespected and, if unresolved, damage the relationship itself. I worked with one leader, Mike, who modelled remarkable countercultural behaviour in this respect. If Mike were in a meeting that looked like it may need to overrun, he would: (a) pause the meeting briefly (irrespective of how ‘senior’ or ‘important’ the person was whom he was with); (b) speak with whomever he was due to meet with next (irrespective of how ‘junior’ or ‘unimportant’ that person was); (c) check if it would be OK with them to start their meeting later or, if needed, to defer it; and (d) take personal responsibility to resolve any implications that may arise from that rescheduling. Needless to say, Mike’s integrity and respect earned him huge loyalty, admiration and trust. When have you seen great models of personal leadership? How do you deal with a no show?

‘You are the hope of the nation!’ (Jasmin, a teacher, the Philippines) It’s intriguing, the impact that teachers can have in our lives. How they shape our experiences, perspectives and choices. I had one teacher who was a sadistic bully. He used his power punitively to evoke terror. As children, we felt fearful and powerless before him. It galvanised within me a later commitment to human rights, to defend the oppressed from powerful oppressors. I had other teachers who opened-up the world to us. One was French, and attractive with a sweet accent. She believed in me and fuelled my interest in languages. Another was English but taught us German. He showed us photographs from his visits and evoked a sense of adventure, an exciting world beyond our horizons of experience. He inspired me to visit different countries. I had another teacher who protected me. I switched classes without permission and, when an angry tutor came to check where I was, this teacher covered for me. It was a moment of unexpected and undeserved grace. He put himself at risk in order to protect me from punishment. It taught me to step out for others, to put myself on the line to protect those who are vulnerable. One teacher had a passion for language. He could create magic with words, enabled us to capture and express ideas with creativity and precision. He enabled and inspired me to write, play with words and reach for excellence. I had another English teacher who toyed with us and manipulated the class for his own entertainment. He taught me to avoid a misuse of position. In all these cases, I was influenced as much by the person as by the subject. It was the person who shaped my world, fanned my passions into flame or served as a warning of what to avoid. I learned important lessons about power and humility, the power to liberate and the potential to abuse. These evolved into central themes in my Christian ethics, stance and leadership. Which teachers have influenced you most? What impact have they had in your life? ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it think.’ (Mark Lawson, Twisted Idioms)

My mind, heart and soul have been turned upside down, inside out. I’ve had the privilege and, at times, intense discomfort of being mentored by a Chinese coach and Christian pastor. I half-jokingly call her Why, rather than her real name Wei, because of her courage and tenacity in pressing deeper, innocently, with the next question. My usual subconscious ways of getting myself off the hook have failed miserably. My beliefs, values and behaviour have all been thrown into question. Wei’s natural orientation towards critical reflexivity means she examines her own attitudes and behaviour transparently – and reflects on them honestly first. She displays child-like curiosity with adult wisdom. She’s far more interested in following God authentically in her life and work than in preserving a superficial relationship or presenting a perfect front. To show real love is more important to her than to win an argument. Her spiritual maturity humbles and inspires me. A person like this presents more than a skill. They demonstrate leadership-by-example. I became aware, over time, of situations in my own life and work that I could have handled very differently; of some of my own defensive routines that I didn’t even know I had. I discovered that I sometimes dig my heels in (something that will, no doubt, come as no surprise to people who know me) and that I can be, at times, more concerned with establishing ‘truth’ than building true relationship. What I experienced here is, I believe, one of the great gifts of leadership, mentoring and coaching. It’s an encounter with a real person that can evoke and provoke fresh awareness and insight. A role model represents an invitation, not an expectation. She or he can inspire curiosity and a desire to think, learn and grow. When have you encountered transformational presence? How do you demonstrate it in your own leading, mentoring or coaching practice? I’d love to hear from you! Anita asked during a coach training workshop this week if it’s appropriate to address emotion in coaching. After all, isn’t that stepping too far into a person’s personal space or risking a drift into therapy? Curious, I asked which dimension of the issue she was feeling most concerned about. Anita replied that she felt anxious about straying into what could feel like a counselling relationship. If she did, she said, she would feel both out of her depth and as if she had breached a professional boundary. I paused, then asked if it had felt inappropriate when I posed that question to her, or if she had felt compromised in how she answered it. She looked up, smiled and said, ‘No.’

Another coaching workshop and Brian, a colleague, was introducing reflecting back as a core skill. One participant looked increasingly frustrated and eventually blurted out, ‘You call this a skill but it’s like playing a game with someone, using techniques on them rather than holding a real and respectful conversation.’ Brian listened then responded calmly, ‘So, reflecting back feels to you like toying with someone, and that clashes with your value for authenticity.’ 'Yes – that’s it exactly!’ he replied with a burst of positive energy that took everyone in the room by surprise. After a brief moment, he and everyone else broke out in fits of laughter. ‘OK, now I get it.’ The principle here is that of modelling an idea, an approach, a method or a technique, rather than simply describing or explaining it. There’s something about experiencing that can feel profoundly and qualitatively different to understanding a concept purely intellectually. This insight lays at the heart of Gestalt coaching and experiential learning. It’s primarily about doing, not thinking, and seeing what emerges into awareness when we do it. I worked with a leadership team that agreed a set of and behaviours to govern its practice. It looked neat on flipchart paper but its potential for transformation didn’t emerge until they grasped the nettle and practised it. What have been your best examples of learning by experience? How do you model this principle in your work with others? The boy looks about 13, maybe 14, and is guiding cars into parking spaces. The sun is beating down and its steaming hot. Exhausted, he sits down against a wall for a break. This is in the Philippines last week. A poor woman from Samar, Jasmin, notices him out of the corner of her eye as she steps down off a jeepney – a mini-bus used for public transport. The boy looks weak and unwell. She walks across to him, speaks gently then reaches out and touches his face with her hand. His skin is burning with a fever. Jasmin urges him to stay there and wait for her as she rushes quickly to find a shop where she can buy medicine, food and drink. Then she returns and says she will take him home, to the slum area where he lives. She reassures him that things will be OK, that she will give his family the equivalent of what he could earn in 2 weeks, along with the food, so that he could take a rest to recover. The boy looks up at this stranger, can’t speak…and just cries. She helps him into a jeepney and honours her promise. I ask Jasmin why she has taken such a risk, to touch a person with clear signs of a fever when the Philippines is in the midst of a Covid-19 lockdown. She looks emotional now and says, quite simply, ‘I imagined how I would have felt if I was that teenager.’ She couldn’t bear to leave him alone, so very sick. She gave what little she had so that his family would not become destitute. I flash back to the parable of the good Samaritan. Jasmin loves Jesus and is willing to engage. I might well have just walked by. ‘They may forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.’ (Maya Angelou) It was a dire and inspiring experience, a hospital for children with severe disabilities in a desperately poor country under military occupation. Conditions were severe, the children were abandoned by their families and the staff were often afraid, suspecting the children were demon-possessed and, therefore, holding them disdainfully at arms’ length. A fellow volunteer, Ottmar Frank, took a starkly different stance. He was a humble follower of Jesus and I have rarely witnessed such compassion at work. I asked him what lay behind his quiet persistence and intense devotion. He said, ‘I want to love these children so much that, if one of them dies, they will know that at least one person will cry.’ Ottmar’s words and his astonishing way of being in the world still affect me deeply today; the profound impact of his presence, and how my own ‘professional’ support and care felt so cold by comparison. I remember the influence he had on others too – how, over time, some others started to emulate his prayer, patience, gentle touch and kindness – without Ottmar having said a word. It invites some important questions for leaders and people, culture and change professionals. If we are to be truly transformational in our work, how far do we role model authentic presence and humanity, seeing the value in every person and conveying through our every action and behaviour: ‘You matter’? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed