|

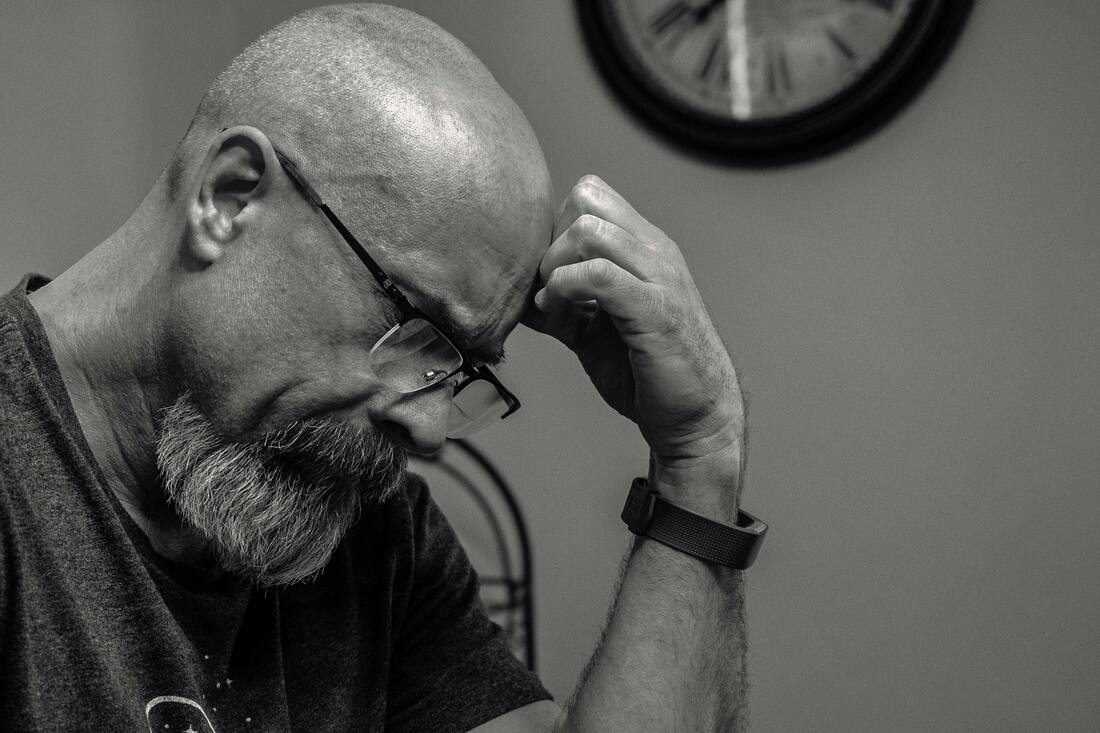

‘Curiosity killed the cat, but for a while I was the suspect.’ (Steven Wright) Action Learning facilitators sometimes feel anxious if there are prolonged periods of silence in a group, or if an individual is particularly quiet. They may assume, for instance, that the person is uninterested to engage with the group or the process. I had that experience once (online) where a participant sat throughout a round wearing headphones, nodding and swinging in his chair as if to music. When I asked if he had any questions, he clearly had no idea what the presenter had been talking about. I addressed this with him directly after the round, checked if there was anything he would need to be and feel more engaged, then agreed that he would leave the set. That said, there are a wide range of potential factors that may influence if and how a person engages in a set meeting and, at times, different reasons for the same participant during different rounds. I will list some of them here as possibilities: if a person has been sent to a set, rather than has chosen freely to join it; if there is formal or cultural hierarchy within the group; if there has been insufficient attention paid to agreeing ground-rules for psychological safety; if building relational understanding and trust has been neglected; if a person doesn’t like someone else in the group, or fears negative evaluation by others in the set; if a person lacks confidence. There are other possibilities too: if a person has an introverted preference and processes thoughts and feelings internally; if a person has a reflective personality and needs more time to think; if a person doesn’t feel competent with the language or jargon being used; if the person can’t think of a presenting issue or a question; if last time the person spoke up in a group meeting, it was a difficult experience or had negative consequences; if a person is preoccupied with issues or pressures outside of the meeting; if a person is distracted mentally or impacted emotionally by something that happened before the meeting, or is due to happen after it. So, what to do if a person is completely silent in a set? Here are some ideas, to be handled with sensitivity and, if appropriate, outside of the meeting: take a compassionate stance – there may be all kinds of reasons for the silence of which you are unaware; avoid making judgements – silence does not necessarily indicate disengagement; be curious – ask the person tentatively, without pressure, if any issues or questions are emerging for them; avoid making assumptions – ask the person what the silence means for them and if there’s anything they need; have an offline conversation with the person – if their silence persists for more than one meeting.

16 Comments

'95% of what we think we know, we have simply accepted from what other people have told us.' (Dennis Hiebert) Nothing adds up. How can we identify hidden assumptions, implicit agendas and vested interests that lay behind what we see, hear and read in the media? Perhaps the answer to this question has rarely been so critical. Democracy and social cohesion within and between peoples and nations are threatened by manipulation and misrepresentation of what we may ordinarily regard as truth. Following writer Mark Twain, actor Denzel Washington commented famously, ‘If you don’t read the news, you’re uninformed. If you do read the news, you’re misinformed.’ Take international news in the UK. Why are we so focused on Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Gaza? Why haven’t we noticed, apart from the occasional glance, the terrible civil wars in Sudan, Myanmar or Democratic Republic of Congo? Why do we call Russia’s brutal intervention in Ukraine a ‘full-scale invasion’? Why do we assume that increasing NATO size-spend is the only solution? If Israel’s bombing is indiscriminate, why has it killed, proportionately, so few ‘adult men’? Why didn’t we see outraged street demonstrations against horrific, widespread atrocities by Daesh? These are profoundly important, deeply complex and extremely painful issues and we rarely have access to the underlying research or information that could help us, as ordinary and concerned citizens of the world, to discern and decide how to act. We are presented with multiple, competing viewpoints and demands and this can feel both perplexing and paralysing. I don’t know the answers to such questions yet I do believe they should play at least some part in shaping my response. I will share some considerations that may help us to avoid sleepwalking blindness. As we’re exposed to news reports, what are we noticing and not noticing? How far does what we’re noticing appear to confirm what we already believe or want to believe? How open are we to having our assumptions, our preconceived beliefs and ideas, challenged to reveal something different or new? Why is the news presenter or media channel presenting this particular story or angle? What do they want us to believe, think, feel or do? Who or what is being excluded by the reporter’s narrative? Whose voice, perspective or experience is being ignored or filtered out? Behind the scenes: who owns and-or funds the media channel, the presented report or the research that underpins it? How rigorously are research methods tested to avoid implicit bias? Are views and experiences presented in a report genuinely representative of a wider and diverse population, or different sides to a conflict? In interpreting statistics, is a reporter presenting a case selectively, or cherry-picking results to show or advocate a particular stance? In short, be sceptical – and look for evidence that supports or contradicts the research-reporter’s ‘news’. ‘Language is power, life and the instrument of culture, the instrument of domination and liberation.’ (Angela Carter) In her challenging and ground-reclaiming polemic, Drop the Disorder, psychotherapist Jo Watson comments that, “The counselling profession (and in that I include psychotherapy) is helping to endorse a medical understanding of emotional distress that is based on ‘What is wrong with you?’ and not ‘What has happened to you?’” I heard a similar-but-different reframing of the issue from Paul Kelly at a Leading & Influencing Trauma-Informed Change workshop today, advocating a shift from “What’s the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?” The striking feature of both these examples is the profound impact of language on reflecting and reinforcing the ways in which people and situations are construed and responded to. In Jo Watson’s case, the first framing regards an issue as some form of dysfunction in an individual. The alternative looks beyond the individual to explore wider potential influencing factors. As radical social reformer Martin Luther King noticed, what appears at first glance as dysfunctional behaviour is sometimes a normal response to dysfunctional circumstances. In Paul Kelly’s case, similarly, the first framing locates a problem within an individual. It’s a form of pathologizing, implying that a person’s behaviour is a consequence of some internal defect. The alternative invites an exploration of the person’s underlying values and motivations. Behaviour that appears dysfunctional could be a natural response to healthy, unmet hopes and needs in a dysfunctional environment. Kenneth Gergen offers a stark warning here, pointing to risks of a medical model applied uncritically: ‘a diseasing of the population.’ ‘The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.’ (John Maynard Keynes) Once upon a time…I would often get tens if not, on occasion, hundreds of responses to blog posts on LinkedIn. It was a thrilling experience to receive insights, ideas and experiences from people all over the world. Over time, however, the huge flood of responses gradually diminished to a tiny trickle. I felt surprised, disappointed and bemused. What had changed? I began to ask myself some searching questions: Were people bored with my content? Were fewer people using LinkedIn than before? Were fewer people engaging with posts on LinkedIn generally? I looked at which posts seemed to be getting lots of responses and noticed that they often looked more like Facebook posts: e.g. walking a dog, taking a child to school. This set me off down a different track. Had there been a shift in societies so that people were no longer interested in thinking through issues and more interested in sharing personal experiences? Had Covid lockdown and isolation shifted our focus from insights and ideas towards the social and relational, to feel less alone? Had we all slipped into a TikTok world? The problem was, I was asking the wrong questions. My starting assumption was that the critical issue was with my blog content. It led me, like Alice in Wonderland, down perplexing rabbit holes. It took a revelatory conversation with a marketing consultant, James Rowe, to discover the core issue was with my media, impacted by changes to LinkedIn algorithms. What assumptions are you making? How do you avoid getting stuck? ‘Action Learning aims to shake you out of the cage of your current thinking.’ (Pedler & Boutall) Action Learning: a method by which someone receives stretching, coaching-type questions from a small group of peers. The aim is to resolve a pressing challenge, a real-life/work issue that has left the person perplexed or stuck. The idea is to leave with actions, practical steps that will help to move things forward. Yet what gets a person stuck in the first place? If it’s a complex challenge, such as that of navigating the intricacies of diverse human relationships, we may become inadvertently caged by our own assumptions. Gareth Morgan commented that ‘people have a knack for getting trapped in webs of their own creation.’ If we don’t know what assumptions we’re making, everything may seem self-evident to us. This is where Action Learning and coaching really can help. If we can engender a spirit of curiosity within ourselves and invite challenging questions from different others, we may discover a door emerging in our previously-unseen cage, experience the agency to push it wide open and step outside to embrace fresh possibilities. It could just change...everything. ‘Behind every problem, there is a question trying to ask itself. Behind every question, there is an answer trying to reveal itself.’ (Michael Beckwith) Second-guessing. It creates all sorts of risks. ‘What time does Paul’s meeting finish?’ Is that a simple request for information, or is there a question behind the question? ‘I’d like to meet with Paul this afternoon. What time will he be free?’ That’s better. ‘I need you to present an urgent strategy update to the Board.’ Again, is that a simple instruction, or is there an issue that lays behind it? ‘I’d like to demonstrate to the Board next week that our investments are achieving the desired results.’ Better. A problem with a question that fails to reveal the question, the issue, that lays behind the question is that it leaves the other party to fill in the gaps. In doing so, they are likely to draw on their own assumptions – which could be very different to your own – or sometimes their anxieties. ‘Is he complaining that Paul’s meeting is over-running?’ ‘Is she inferring there’s a problem with my work on strategy delivery that I hadn’t been aware of?’ Simply stating our intention can make all the difference. ‘You can never really know someone completely. That’s why it’s the most terrifying thing in the world, really – taking someone on faith, hoping they’ll take you on faith too. It’s such a precarious balance. It’s a wonder we do it at all.’ (Libba Bray) There’s an idea in Gestalt psychology that we’re predisposed, hard-wired, to ‘fill in the gaps’. Here’s a real and practical example. I was once invited to facilitate a conference of around 50 people from diverse professional backgrounds in the housing sector. I had never met anyone in the group and they had never met me. I stood up on the podium, introduced myself simply as ‘Nick Wright, an organisation development consultant from England’, then invited everyone to take a pen and paper. I explained that I would ask them a series of questions about myself, to which they were to guess the answers. ‘Which newspaper do I read?’ ‘What political party will I vote for at the next General Election?’ ‘Am I married, or single?’ ‘What is my professional background?’ ‘What’s my favourite hobby outside of work?’ I then asked who had been able to answer every question. Everyone raised their hands. I now invited them to draw a simple face against each of their answers – which they wouldn’t be expected to share in the group. A happy face meant their answer drew them towards me; an unhappy face that it pushed me away. A neutral face meant, well, neutral. Again, everyone managed to do it. I paused and invited them to reflect at their tables on what had just happened. Person after person said how astonished they felt at how quickly and easily they had created a profile of me in their minds, and how that had influenced how they felt about – and were now likely to respond and relate to – me. They had filled in the gaps of not-knowing by drawing on hopes and fears, past experiences, personal projections, cultural assumptions etc. Filling in the gaps enables us to relate quickly to others rather than starting every relationship as if from scratch. It also risks unhelpful stereotyping and bias. This raised important questions for participants at the conference so I offered 3 principles: compassion, curiosity and challenge. Compassion: ‘What do I need to feel safe to contribute in this group? ‘How can I demonstrate a compassionate stance towards others?’ Curiosity: ‘What assumptions am I making about those around me, e.g. based on their looks, accent or job title?’ ‘Who or what is influencing the ways in which I’m thinking about, feeling about and responding to others?’ Challenge: ‘What am I not-noticing about those around me?’ ‘How open am I to have my beliefs about others tested?’ ‘The map of the world is always changing; sometimes it happens overnight. All it takes is the blink of an eye, the squeeze of a trigger, a sudden gust of wind.’ (Anderson Cooper) I ordered a large and colourful map of South East Asia for my bedroom wall recently. When it arrived, it was subtly different to the one that had been advertised and clearly depicts a Chinese geopolitical view of the region. Taiwan is colour-coded the same as China and the internationally-disputed 9-dash line is boldly marked around the whole of the South China Sea. It struck me how simple representations on a map can both reveal and aim to create a very specific cultural and political view of the world. I have another large and colourful map of the Earth mounted on the wall above my desk. This one shows the world as ‘upside down’, although the names on the ‘countries’ are still written the ‘right way up’. It feels strange and disorientating to look at and reveals, experientially, how fixed we can become in the representations we hold of of the world we have been taught and learned since childhood. A world map is also a mental map. Every portrayal is an implicit human construct. Nothing is simply ‘how it is’. 'There is no act too small, no act too bold. The history of social change is the history of millions of actions, small and large, coming together at critical points to create a power that governments cannot suppress.' (Howard Zinn) At the heart of coaching generally lays a desire and opportunity for impact and change, a goal that may seem obvious, but one that raises important questions. As coaches aspiring to make a difference in the world, we can find ourselves navigating complex dilemmas. When we work with agents of change in, say, NGOs, charities, churches or public sector organizations, we often seek to empower individuals, teams, and organizations to be resourceful and effective in achieving transformation. One challenge we may encounter is determining the coaching agenda. A Western coaching ethic advocates for giving the client complete control over the agenda, focusing on their chosen goals and boundaries. While this approach seems straightforward, our intention of promoting social change may lead us to contemplate how much influence we should exert on the client’s journey. What if the client's solutions seem unethical, ineffective, or could pose risks to broader social development? Furthermore, when working in diverse cultural contexts, we need to be mindful of differing perspectives on individual autonomy. In some Eastern and Southern cultures, the concept of setting individual goals might not resonate the same way it does in the West. People in these cultures often prioritize the wishes and expectations of a wider group, whether family, team or community, before their own hopes and ambitions. We could risk inadvertently imposing our own cultural values onto the client. The solution often lays in recognizing the significance of context and building a strong and trusting relationship with the client. By understanding the dynamics of power, language and agendas that may emerge between us, we can gain insight into the issues at hand and potential solutions. We become allies, working together to achieve meaningful impact. A critically-reflective process allows us to adapt our coaching practice on route and to challenge our assumptions as we learn and grow. ‘It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.’ (Henry David Thoreau) Psychologist Albert Ellis, widely regarded as the founding father of what has today evolved into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, noticed that different people responded differently to what were, on the face of it, very similar situations. Previously, you might have heard, ‘Person X feels Y because Z happened’. It assumed a direct causal relationship between emotions and events. Ellis’ observations challenged this, proposing that something significant was missing in the equation. After all, if this assumption were true, we could expect that everyone should feel the same way in circumstance Z. Curious about this, Ellis concluded that the critical differentiating and influencing factor that lays between emotions and events is belief. It’s what we believe about the significance of an event that affects most how we feel in response to it. Here we have person A who hears news of a forthcoming redundancy with fear and trepidation. He believes it will have catastrophic financial consequences for himself and his family. Person B receives the news with positive excitement. She believes it will provide her with the opportunity she needs to pursue a new direction in her career. Drawing on this insight, organisational researchers Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal proposed that, in the workplace, what is most important may not be so much what happens per se, as what it means. The same change, for instance, could mean very different things to different people and groups, depending on the subconscious interpretive filters through which each perceives it. Such filters are created by a wide range of psychological, relational and cultural factors including: beliefs, values, experiences, hopes, fears and expectations. This begs an important question: how can we know? Hidden beliefs are often revealed implicitly in the language, metaphors and narratives that people use. To observe the latter in practice, notice who or what a person or group focuses their attention on and, conversely, who or what appears invisible to them. Listen carefully to how they construe a situation, themselves and others in relation to it. Inquire in a spirit of open exploration, ‘If we were to do X, what would it mean for you?’; ‘If we were to do X, what would you need?’ This is about listening, engagement and invitation. Attention to the human dimension can make all the difference. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed