|

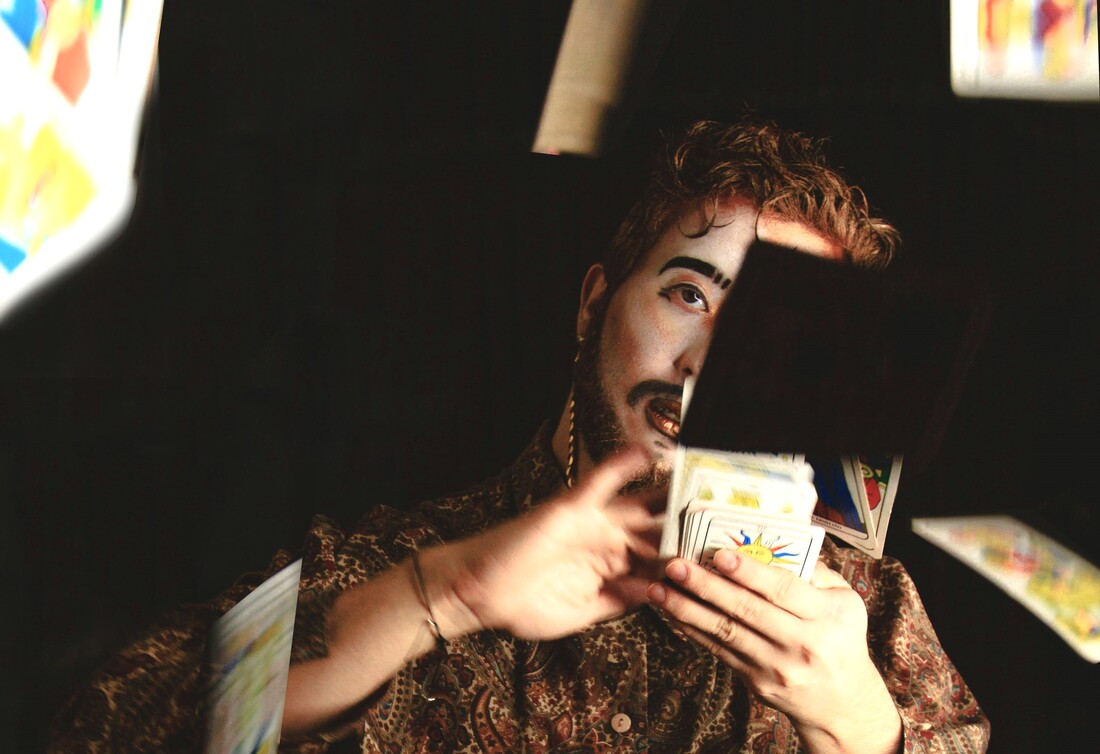

‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers)

10 Comments

‘Just like seasons change in nature, they change in our lives as well. And, as they change, they ask different questions of us. What questions is your life asking of you now?’ (Funmi Johnson) I had a great conversation with Funmi, a fascinating and inspiring fellow coach, this afternoon and found her question (above) very thought-provoking. I’m at an age where legacy is a persistent question that calls out to me with growing insistence…and demands a response. Am I genuinely living my life authentically according to the mission and values that I claim to be real and true? Or am I compromising too much of what matters most, deluding myself with a clever façade that even I have found convincing? How deep will my spiritual footprint be? I love Funmi’s question. It stirs the waters and ignites a search. ‘Learn from history, maintain your mystery, take your victory.’ (Amit Kalantri) Sometimes, we need to look back to look forward and the New Year can present us with a special opportunity to do just that. We could think of this as analogous to an annual performance review, where we pause for a moment and take stock of progress and learning so far before moving on. At a personal level, I’ve been thinking and writing quite a lot recently about Kairos moments in my own life that have, in retrospect, often proved pivotal. These experiences carry a spiritual quality and significance for me that both transcend the temporal and reveal a deeper sense of meaning. An instance comes to mind when, 3 days into a leadership role in a new organisation (to me), my line-manager called me into his office to confess, in deep disappointment, that funding for (a) a new leadership coaching programme and (b) a new management development programme, both of which were to lay in my area of responsibility, had been slashed as part of broader financial cuts. He apologised that, as a consequence, these flagship initiatives could no longer go ahead. I could see a look of anxiety on his face wondering, I imagine, how I might react to this bombshell news. I prayed silently then responded in a spirit of curiosity that, if these initiatives were priority, I’d just need to find a different way to achieve them. I thanked him for being open, prayed, then placed an invitation on LinkedIn, asking if anyone would like to offer pro bono coaching support for leaders in a national UK charity. Within 10 days, 180+ people had responded to offer their services. I also prayed and asked around if anyone would be willing to run a pro bono management development programme. A prestigious agency responded and ran an annual programme for us for 4 years running. I’m reflecting on why this experience came to mind for me now. It happened 10 years ago yet still feels so profoundly resonant as we approach the New Year. The first lesson for me is that it’s not all about me. God is capable of doing far more than I can ask or imagine. The second is the rich relational resourcefulness of networks, the kindness of so many people who are willing to offer themselves in heartfelt service when offered meaningful opportunities to do so. The third is the power of invitation, not expectation, that draws people freely into co-creative partnership to do something amazing. ‘Human existence is always directed to something, or someone, other than itself – be it a meaning to fulfil, or another human being to encounter lovingly.’ (Viktor Frankl) Existential coaching is a powerful and introspective approach that can empower individuals and groups to confront life's fundamental questions, find meaning and embrace personal and social responsibility. Rooted in existential philosophy, this coaching method guides clients through self-exploration, enabling them to confront their fears and uncertainties and make authentic choices aligned with their values. Here are some examples of existential coaching questions:

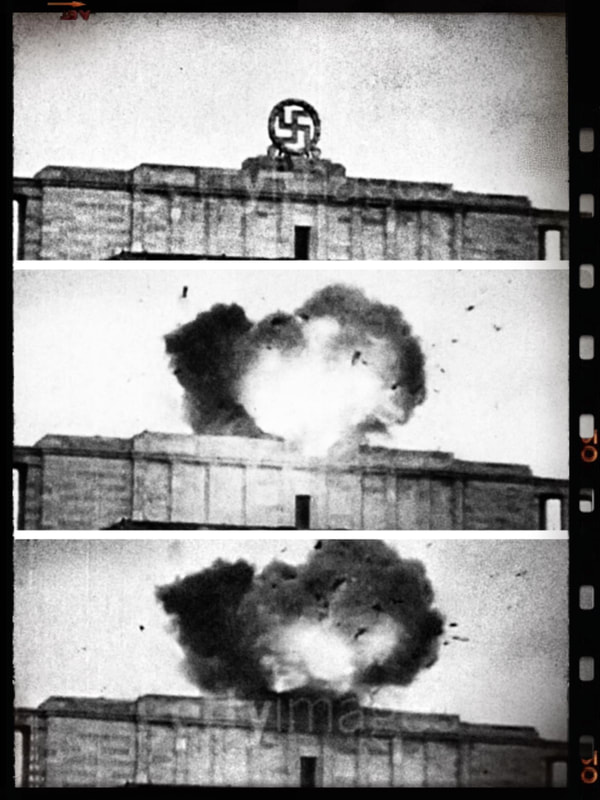

Existential coaching recognizes that we all face inherent dilemmas, and embracing these challenges can lead to personal and social growth. Using this approach, the coach serves as a supportive ally, helping clients to confront their concerns, explore their inner personal-cultural truths and develop a deeper understanding of themselves. The client can learn to navigate life's complexities with greater clarity and intention, leading to a more meaningful and purposeful life. [Further reading: Monica Hanaway, The Handbook of Existential Coaching Practice (2020); Yannick Jacob, An Introduction to Existential Coaching (2019); Emmy van Deurzen & Monica Hanaway, Existential Perspectives on Coaching (2012)] ‘When the winds of change blow hard enough, the most trivial of things can turn into deadly projectiles.’ (Despair.com) You’ve probably heard of change management. You’ve probably heard of change management teams too. You’ve probably heard of change plans, like project plans, sometimes expressed in Gannt charts with rows of scheduled tasks, mapped against proposed timeframes. You’re less likely, I would guess, to have heard of a transition plan. A transition plan deals with the human dimensions of change, the underlying psychological, emotional and relational issues that often prove critical to its success. Whilst change can often be planned and prepared for by agreeing desired outcomes, then working backwards to identify the practical steps needed to achieve them (a bit like working out the mechanical structure of a car engine in order to build one), transitions don’t work like that. A change process may be complex, in that there may be many interlinked moving parts, yet is in principle manageable. A transition process is dynamically-complex and, therefore, inherently unpredictable. This means that transitions can only be handled effectively by ongoing conversations with affected people. It calls for open and honest dialogue. It calls us to be invitational, curious and co-creative. It involves listening, hearing, being responsive and building trust. ‘If we were to do X…what would it mean for you?’ ‘Given what it would mean for you, what would you need?’ Well-led transitions will influence mood, climate, energy, engagement and agency: critical success factors in any change. ‘What is most important about any event is not what happens, but what it means.’ (Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal) Here’s one way to think about human change and transition: change is what happens around us and transition is what happens within us. Imagine, for instance, a change at work – ‘We used to do X and now we’re going to do Y instead.‘ Simple, right? It can be, yes…except when it isn’t. It all depends, at heart, on what that change will mean to a person, team or organisation, and-or what it could mean for others that matter to them too; e.g. colleagues, family, friends, people who use their services. It can get more complicated still. The same change could mean different things for different people and groups. It could also mean different things for the same person or group e.g. at different times, depending on what else is going on for them. In practice, this means that to support people through transitions, change leaders do well (a) to avoid making assumptions about what a change will mean and (b) to explore, ‘What will this change mean for you?’; then, given that, ‘What will you need?’ I can almost hear some leaders crying out in protest, ‘Don’t be naïve, Nick. Be realistic. People don’t like change. They’re resistant to change.’ Yet, here’s the thing. People will sometimes resist change, even though they agree with it, if they don’t feel heard or understood. Conversely and paradoxically, people will sometimes support change, even if they disagree with it, because they do feel heard and understood. Working with transitions isn’t an optional add-on. It can prove the key to success. ‘How is that human systems seem so naturally to gravitate away from their humanness, so that we find ourselves constantly needing to pull them back again?’ (Jenny Cave-Jones) What a profound insight and question. How is that, in organisations, the human so often becomes alien? Images from the Terminator come to mind – an apocalyptic vision of machines that turn violently against the humans that created them. I was invited to meet with the leadership team of a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in East Africa that, in its earnest desire to ensure a positive impact in the lives of the poor, had built a bureaucratic infrastructure that, paradoxically, drained its life and resources away from the poor. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. I worked with a global NGO that determined to strengthen its accountability to its funders. It introduced sophisticated log frames and complex reporting mechanisms for its partners in the field, intended to ensure value for its supporters and tangible, measurable evidence of positive impact for people and communities. As an unintended consequence, field staff spent inordinate amounts of time away from their intended beneficiaries, completing forms to satisfy what felt, for them, like the insatiable demands of a machine. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. A high school in the UK invited me to help its leaders manage its new performance process which had run into difficulties. Its primary focus had been on policies, systems and forms – intended positively to ensure fairness and consistency – yet had left staff feeling alienated, frustrated and demoralised. We shifted the focus towards deeper spiritual-existential questions of hopes, values and agency then worked with groups to prioritise high quality and meaningful relationships and conversations over forms, meetings and procedures. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. Academics and managers at a university for the poor in South-East Asia had competing roles and priorities, and this had created significant tensions as well as affected adversely the learning experience of its students. The parties had attempted unsuccessfully to resolve these issues by political-structural means; jostling behind the scenes for positions of hierarchical influence and power. They invited me in and we conducted an appreciative inquiry together, focusing on shared hopes, deep values, fresh vision and a co-created future. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. Where have you seen or experienced a drift away from the human? Curious to discover how I can help? Get in touch! ‘It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.’ (Henry David Thoreau) Psychologist Albert Ellis, widely regarded as the founding father of what has today evolved into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, noticed that different people responded differently to what were, on the face of it, very similar situations. Previously, you might have heard, ‘Person X feels Y because Z happened’. It assumed a direct causal relationship between emotions and events. Ellis’ observations challenged this, proposing that something significant was missing in the equation. After all, if this assumption were true, we could expect that everyone should feel the same way in circumstance Z. Curious about this, Ellis concluded that the critical differentiating and influencing factor that lays between emotions and events is belief. It’s what we believe about the significance of an event that affects most how we feel in response to it. Here we have person A who hears news of a forthcoming redundancy with fear and trepidation. He believes it will have catastrophic financial consequences for himself and his family. Person B receives the news with positive excitement. She believes it will provide her with the opportunity she needs to pursue a new direction in her career. Drawing on this insight, organisational researchers Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal proposed that, in the workplace, what is most important may not be so much what happens per se, as what it means. The same change, for instance, could mean very different things to different people and groups, depending on the subconscious interpretive filters through which each perceives it. Such filters are created by a wide range of psychological, relational and cultural factors including: beliefs, values, experiences, hopes, fears and expectations. This begs an important question: how can we know? Hidden beliefs are often revealed implicitly in the language, metaphors and narratives that people use. To observe the latter in practice, notice who or what a person or group focuses their attention on and, conversely, who or what appears invisible to them. Listen carefully to how they construe a situation, themselves and others in relation to it. Inquire in a spirit of open exploration, ‘If we were to do X, what would it mean for you?’; ‘If we were to do X, what would you need?’ This is about listening, engagement and invitation. Attention to the human dimension can make all the difference. Few images have more powerful emotional resonance for me than that moment at which the WW2 Allies detonated explosives under a huge marble swastika at the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nürnberg, Germany. It was the place where, just before the war, Hitler and his followers had held their infamous Nazi rallies. The rallies had proved a potent propaganda weapon, convincing Nazi supporters of their own ‘supremacy’ and intimidating their enemies into fearful submission. The public destruction of this infamous symbol marked the impending final demise of the deranged Nazi myth and its psychopathic regime, and the end of by far one of the worst eras in human history. I can only imagine how it must have felt for those who had suffered so terribly to witness, at last, this emerging glimmer of hope. Similar evocative and symbolic moments were soon to follow with a Soviet flag over the German Reichstag and an American flag raised on Iwo Jima. There’s something about these images-as-symbols that capture and express a wider human story and experience. They carry and convey powerful psychological, cultural and emotional meaning for those who understand and identify with what they represent. Other well-known examples of symbols include the Christian cross as a sign of God’s love and salvation through Jesus Christ or, conversely, ominous ‘Z’ insignia on Russian military vehicles during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. What symbols have a particular resonance for you – and why? ‘I know you believe you understand what you think I said but I'm not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.’ (Alan Greenspan) Clarity. Simple in principle, not always easy in practice. Paradoxically, a significant challenge to communication is human language. Words intended to build a bridge can so easily create a barrier. We may use the same words but mean something different things by them or use different words to mean the same thing – and very often without realising it. Linguists explain that words are connotative as well as denotive. This implies that their meaning, the associations they hold and the feelings they may evoke can shift markedly depending on context, culture, tone and relationship. We may say something in irony. We may tell a joke with a straight face. We may make a harsh-sounding comment with a glint in our eye. We may make subtle gestures that fill in the gaps in verbal conversation. According to Transactional Analysis, we may make a statement at one level with an intention and implied meaning that’s completely different to the literal. These nuances challenge the limits of neuroscience and artificial intelligence. As social construction expert Kenneth Gergen asserts, ‘Neurobiology can tell us a lot about a blink, but nothing about a wink.’ I facilitated an astute cross-cultural group of women last week who practised skills of curiosity and inquiry. Instead of responding immediately to what they thought another person had said or meant – for example, by a statement, phrase or word – they would test their own assumptions by actively exploring that person’s intended message and meaning. It created a dynamic of interpretation based on dialogue, in contrast to an instinctive reaction to words at face value. It took time, patience, and a commitment to hear and understand. Conversations became richer and relationships grew deeper. It's trickier in online conversations. We can find ourselves subconsciously searching hard for non-verbal cues we would ordinarily pick up when together in the same physical room – yet all we can see is head and shoulders in a 2-dimensional screen frame. This is one of the probable contributors to Zoom fatigue. If you have seen the film ‘Thirteen Days’ (2000) based on the Cuban missile crisis, it’s an extreme opposite example of trying to decode hidden messages and intentions based purely only observation of another party’s actions. It’s Chris Argyris’ Ladder of Inference on steroids. What approaches, tools and techniques do you use to ensure clear communication? (See also: Crossed Wires) |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed