|

‘Chance is perhaps the pseudonym of God when he doesn’t want to sign.’ (Anatole France) I enjoyed a very tasty Eritrean meal with an inspiring young couple today. I had met this bright young man on a plane on my way to Germany last year and we had chatted throughout the flight. It turned out his equally-talented partner is involved in very similar work to my own, including internationally, so we agreed to keep in touch with each other on our return to the UK. As we met up again for the first time today, we talked about our shared faith in Jesus and his profound significance in our lives. We talked, too, about ways in which we’ve witnessed his mysterious power at work. As I listened to this couple's stories and experienced their generosity and warmth, I had a deep sense this encounter was far more than coincidence. When have you experienced encounters that somehow felt sacred?

8 Comments

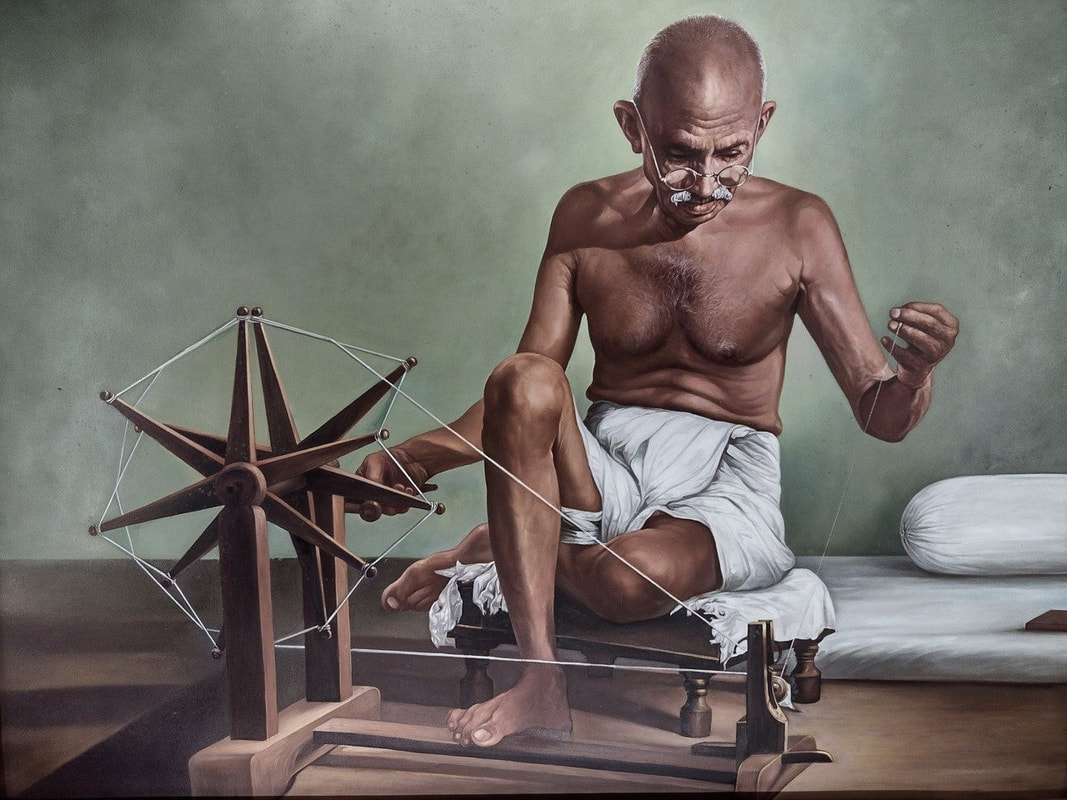

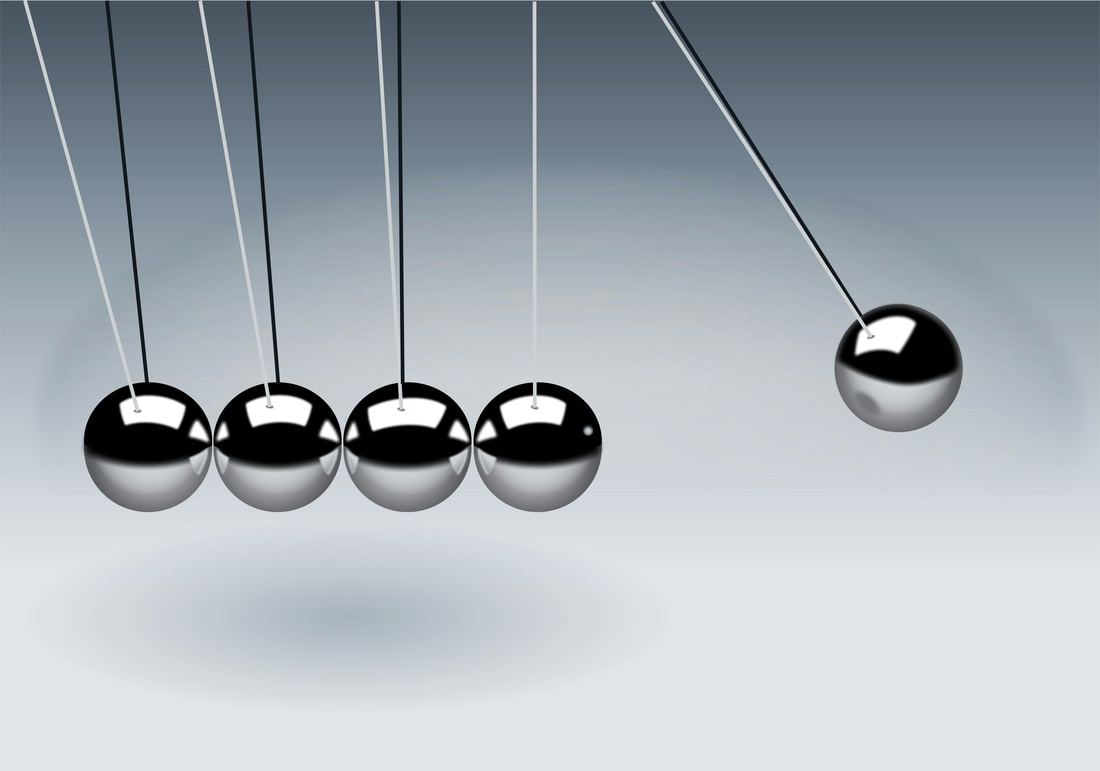

‘Always vote for principle, though you may vote alone.’ (John Quincy Adams) I never had the privilege of meeting Soji Taguchi, but I do wish I had. Soji was a manager at a Japanese-owned textiles factory in the Philippines. Seeing how meagrely the Filipino workers were paid, he gave away a significant portion of his own salary each month to top up theirs. When a young Filipina was severely distressed one day and, in her upset, damaged an expensive piece of machinery, he paid for the repairs himself. Instead of chastising her he listened to her plight and, subsequently, regularly slipped money (secretly) into her pockets to help her, a poor teenager, to pay her bills. This woman’s life is now a clear reflection of his. The power of a positive role-model. Ted Winship was my mentor, a shopfloor supervisor at an industrial site in the UK. Once, the workers refused to enter an enclosure because the conditions in it were so terrible. The manager told Ted that, if he could persuade them to do the work, they would all be paid a substantial bonus. Ted took the manager at his word. He entered the compound first and the work was completed on time. At the end of the project, however, the manager refused to pay the bonus and only gave Ted his. It was a serious breach of trust. On hearing of this betrayal, Ted confronted the manager but to no avail. He distributed his own bonus to the workers, resigned from his job and walked out. Ethics in action. Self-sacrifice for the sake of others. The personal costs were high – but the spiritual benefits were immeasurable. ‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life? ‘Coincidence doesn't happen a third time.’ (Osamu Tezuka) I arrived in the Netherlands on Saturday, aiming to orientate myself briefly to this new country before working with an INGO team there on Monday. When I stepped into my hotel room, however, it smelt damp and sweaty. Trying not to breathe, I opened the windows to an icy blast and decided to go for a walk while the fresh air did its work. Not far away, I noticed a church building so walked over to have a glance at its meeting times. As I did so, I looked up and saw a cross in the sky, a misty symbol painted momentarily on blue canvas by vapour trails. It felt significant, but I didn’t know why. The next day, the church was full when I arrived and I sat quietly in the midst, happily surprised by how much Dutch I could understand. (I can speak German, but this was my first time to read this new language). At the end, a woman kindly introduced herself to me. On learning that I am English, she explained that the church is recovering from an intensely painful internal conflict. The pastor had spoken on a need to look to God. I showed her the photo I had taken the day before – a symbol of suffering and hope – and she started to weep. ‘God brought you here to us this morning, Nick.’ Another woman now introduced herself, explained briefly that she had worked internationally in medical mission, and invited me to a special meeting that afternoon for asylum seekers and refugees. ‘How could she possibly have known anything about my life and work?’ I asked myself, a total stranger. The guest speaker that day was a visitor from Algeria and, serendipitously, works for the same organisation I was about to work with the following day... as does a man who randomly found himself sitting beside me in a hall full of people. Was this all coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide. ‘We don’t have a plane crash scheduled for today, but I thought I’d take you through the emergency procedures just in case.’ (KLM Air Hostess) I love the difference that a sense of humour can make. The air hostess (above) made everyone laugh during the passenger safety briefing on a return flight from the Netherlands today. The airline’s own plane had experienced maintenance problems so it had had to borrow one from another airline. One hostess complained, with a glint in her eye, that the green décor didn't match the blue colour of her uniform. The passengers all laughed when another hostess made an announcement too, aiming to draw our attention to an apparent information light on the plane…only to correct herself moments later with, ‘Oh – this plane doesn’t have one!’ Brilliant. It took the terror out of the turbulence. On a more serious note, I had been in the Netherlands to work with a diverse NGO leadership team, to support its desire to enhance its international teamwork. I referenced briefly a couple of places in the Bible where the writer comments on the amazing potential of human diversity – where the Divine whole is seen, known and experienced to be more than the sum of its parts – yet also hints at the corresponding dark risks of undervaluing, fragmentation and conflict if not. Strikingly, the writer moves on in both places to emphasise a deep need for authentic love as the critical success factor. This insight set a spiritual-existential tone for the day, as we reflected on team-as-relationships. Returning to the plane – but this time as a metaphor, a participant from South Africa asked, ‘How many separate parts is a Boeing 747 aircraft made up of?’ Apparently, the answer is about 6,000,000. ‘And what do these diverse components all have in common?’ Puzzled faces all round now. ‘None of them can fly.’ I thought this was genius. What a great way to dispel the myth of the all-sufficient self in the face of the dynamic complexities of teams, organisations and wider world. We worked through an Appreciative Inquiry next, drawing on positives of the past and aspirations of the present to co-create shared trust and vision for the future. Set the trajectory. Fasten seatbelts. Enjoy the flight. ‘Just like seasons change in nature, they change in our lives as well. And, as they change, they ask different questions of us. What questions is your life asking of you now?’ (Funmi Johnson) I had a great conversation with Funmi, a fascinating and inspiring fellow coach, this afternoon and found her question (above) very thought-provoking. I’m at an age where legacy is a persistent question that calls out to me with growing insistence…and demands a response. Am I genuinely living my life authentically according to the mission and values that I claim to be real and true? Or am I compromising too much of what matters most, deluding myself with a clever façade that even I have found convincing? How deep will my spiritual footprint be? I love Funmi’s question. It stirs the waters and ignites a search. ‘Coincidences are God’s way of remaining anonymous.’ (Albert Einstein) If you ever read David Wilkerson’s The Cross and the Switchblade, you’ll get this. Two weeks ago, a song came to mind that I had written then recorded as a duet with a Christian friend, Maggie, some 37 years ago. Life moved on and Maggie and I hadn’t spoken since. In fact, I had completely forgotten ever having written and recorded that and other songs. Wondering what this mysterious prompt might mean, I rummaged through a box of old items and, to my immense relief, found a cassette with a hand-written label, ‘Niksongs’, on the side. Filled with excitement, I searched online to find some way of copying the cassette to USB so that I could listen to it on my laptop. I found a device designed for that purpose and tried it in eager anticipation but, unfortunately, it didn’t work. Whilst pondering today what to do next, my phone pinged. A message from…Maggie. What?!! Living in Sri Lanka now, she had just found a copy of that very same cassette and was in process of working out how to convert it too – and that was her cue to contact me now. Pure coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide. ‘What is the human being? In our anti-metaphysical age, we regard the question as having little importance. It is, however, the most crucial of all.’ (Felipe M. De Leon) A good friend in the Philippines – St. Paul as I affectionately call him because of his dedication to the Jesus and the poor – works with student educators, teachers of the future. Today, he supported his students to create their own art exhibition as a way of exploring the relationship between art and humanities. It’s a topic that interests me too. I’ve travelled and worked in many different countries in the world but I’ve never encountered a culture as vibrantly and spontaneously artistic and creative as the Philippines. Music, dance and colour are everywhere, and with such natural richness of talent. I find myself wondering – why is this? By stark contrast, in terms of art, my own part of the world can appear and feel quite cerebral, introverted and restrained. (I notice that even using the word ‘feel’ in that sentence can feel edgy and a bit risky in my context.) St, Paul’s students, like so many others I’ve had the great privilege of encountering in the Philippines, inspire me by their passion, energy and uninhibited emotional expression. They danced for me on my birthday even though I’ve never met them before, rather than offering me a simple written greeting. They bring the ordinary things of life to life. In ‘Life as Art’, Felipe M. De Leon makes similar observations and explores cultural and contextual conditions that contribute to this gift-phenomenon. In Filipino society, in which, ‘a person learns to develop an expanded sense of self – a sphere of being which includes not only his (or her) individual self but encompasses immediate family, relatives, friends…closeness to others allows (one) to be more trusting, open and freely expressive. Arts and crafts are richest, most creative and diverse in communal cultures. Food is tastier, speech more melodic and things of everyday life more colourful.’ De Leon goes on to comment on other distinctive dimensions of Filipino culture and spirituality that also play a part. Yet there’s something about the relational dimension that resonates very powerfully with me. I notice when I work with people and groups that, if they feel genuinely loved, valued and involved, they often find themselves at their most free, experimental and creative too. Conversely, if they feel isolated, undervalued or excluded, they are more likely to become defended, closed-in or shut-down. These amazing Filipino students have a lot to teach the Western world, and me…and I’m still learning. ‘If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine.’ (Ernesto Che Guevara) It looked like a scene from Dante’s inferno. Students from a very poor barangay (community) in the Philippines arrived home this week… Delete, rewind: arrived at where their makeshift homes had been until this week, to see them engulfed in a blaze of fire and billowing with thick, black smoke. The poor have no land rights, no insurance and no savings to fall back on. For a moment, it felt like their lives, as well as their homes, had gone up in flames. On hearing of this, one of their tutors, Jasmin, raced to provide them with emergency relief. She offered them a safe place to sleep in her own home, yet they refused – preferring to stay with their families in the midst of the charred and burned-out remains. On receiving her gift of food supplies, they immediately shared it with their extended families and with their neighbours who had lost all too. The next day, their fellow students rallied around in support. Rumours spread quickly that corrupt officials were behind the disaster as a way of driving the poor off the land to sell it to rich property developers – in exchange for a substantial bribe. Being sited at a prime seaside location, and being told immediately by the local Mayor that they would not be allowed to return, added sinister credence to these fears. The barangay residents have no access to justice, yet say they have Jesus as their advocate and hope. Life is hard-edged for the poor. We, too, can be hope. ‘Our reality is narrow, confined, and fleeting. Whatever we think is important right now, in our mundane lives, will no longer be important against a grander sense of time and place.’ (Liu Cixin) I think you could say we’re a family with an international outlook. My parents travelled extensively around the world and have touched most continents. My older brother lived in Brunei, married a Malaysian woman and has visited almost every country in Asia. My sister lived in Germany, mixes with friends from different countries and travels frequently to Spain to do salsa dancing. My younger brother ran a charity for and in Romania, did a medical mission in remote areas of the Amazon jungle and works in Dubai. I’ve been interested in different languages and cultures from childhood, have worked in 15 countries and have visited, have friends in and have worked with people from a lot more. I watch almost exclusively international news, pay special attention to South-East Asia and my home is adorned with globes and colourful maps. Much of my life has been preoccupied with the Nazis and how to use my own life to help avoid anything like such horrific atrocities ever happening again. Against this backdrop, my own coach, Sue, posed two interesting challenges recently: ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – overseas with the poor and vulnerable in far-flung places yet to be, physically, here in the UK?’ and, ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – in World War 2 yet to be, physically, here and now?’ What great questions. They resonate profoundly, for me, with what it is to be a follower of Jesus – a deep dissonance that arises from being in this world, yet in some mysterious way being not of this world. Existentially, it’s a kind of dislocation that, a bit like for Third Culture Kids (TCK), creates a sense of being a child of everywhere yet, somehow, not a child of anywhere – at least in this lifetime. I often feel more at home when I’m away from home, a paradoxical dynamic that both draws and propels me into different times and places and to seek out God, diversity and change. It means being a traveller, not a settler, and has influenced every facet of my entire life, work and relationships. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed