|

‘Clear your mental cache.’ (Gleb Tsipursky) An anchor holds a floating vessel in place to stop it drifting away from where we want it to be. There are many things that could cause it to move, such as a sea tide or river current, so the anchor acts, in effect, as a grounding mechanism. It provides a sense of stability and security in the midst of potential turbulence or unsettling waves. There are parallels, psychologically, in early formative experiences that can influence what we perceive, value and choose as we move through life. These phenomena – often significant people, events, objects or relationships – can form something like anchors in our psyche. They become iconic, or ideal types, that shape our hopes and dreams. A risk is that we place undue value on these anchors in our decisions here and now. This is known in psychology as anchor bias or anchor effect. For example, the first motorbike I fell in love with was a Daytona-yellow Yamaha RD400DX. It has been, since, the bike I always remember most passionately and the standard against which I measure all other bikes. If I were to ride one now, however, the reality may lay far from the idealised fantasy I’ve created over time. I’ve changed a lot over the years and so have motorcycles. I’m older and its vibrating 2-stroke engine might irritate me now. I might feel dismay at its near-lethal early disc brakes or its propensity to rust every time it gets wet. This can happen in relationships too. The first person we fell in love with may become idealised. We may remember vividly the things we loved about them and ignore or forget the things that hurt or annoyed us. We may subconsciously erase or minimise the factors that led to a break-up. As a consequence, we may seek to rediscover or recreate these same idealised qualities in another person or relationship then face hurt, frustration or disappointment when we don’t find them. A solution lays in: recognise our anchors; be aware of our idealising human tendency; learn to see, value and embrace new people, relationships and experiences for who and what they are – in their own unique right.

16 Comments

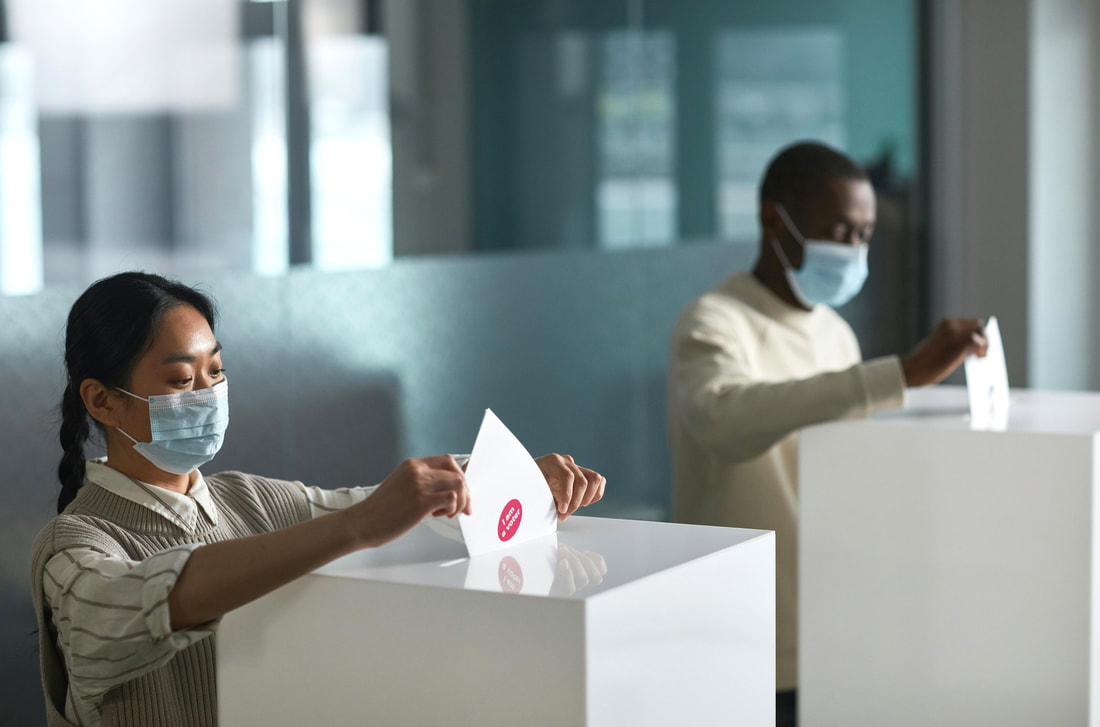

‘Votes are cast based on rational decisions, right?’ (Zaria Gorvett) As I watched the former leader of a very influential nation speak on TV last night with what came across (to me, at least) as a mishmash of delusions and mistruths, I felt, to put it mildly, both bemused and dismayed. This felt even more so because current polls in that country point to a distinct possibility, if not yet a probability, that that person could actually be re-elected to that position of power. I found myself asking myself, ‘What kind of craziness would compel people to vote for this person? How can’t they see through the nonsensical and narcissistic rhetoric?’ Shaking my head with a deep sigh, I got up to make a cup of tea. Suddenly (I don’t know if it was the caffeine), a revelation hit me. I flashed back to some years ago in Germany, watching a 1-hour interview with Angela Merkel on TV. She was at the height of her leadership that year and, to be honest, I could hardly understand a word she said. My German language skills simply weren't up to it. Yet, somehow…I found her absolutely mesmerising. Something about her style, presence and tone subtly seduced me. I would have voted for her. I would have married her! Maybe. This took me back, next, to the Brexit-EU psychodrama in the UK. At that time, arguments flew back and forth vociferously in favour of Leave or Remain. Little I heard on either side bore much resemblance to evidential reality. Noticeably, most people I spoke with voted on instinct, on gut-feel intuition, and were swayed little by spurious claims or counterclaims. Boris Johnson, who won that game (by a narrow margin), played subconsciously on cultural memories of Winston Churchill, the lone hero who stood alone against overwhelming internal and external odds. So, an ex-President, an ex-Bundeskanzlerin and an ex-Prime Minister. It's far more than the words they say. It’s what they symbolise and represent. It’s how they make people feel. ‘When you wish upon a falling star, your dreams can come true. Unless it’s a meteorite hurtling to the earth which will destroy all life. Then you’re pretty much hosed no matter what you wish for. Unless it’s death by meteor.’ (Despair.com Demotivators) I was surprised to return to my desk and find 6 people waiting in a queue to complain. I’d worked hard on my all-staff presentation and thought I’d handled it well. My task had been to present the results of an annual staff survey: the good, the bad and the ugly. I’d attempted to present a view that, even in those areas where scores were low, such scores represented implicit positive hopes and aspirations. If, for instance, someone had given a low score for quality of management, it was because good management matters to them, even if their desires and expectations were unmet. My agitated colleagues saw it differently. They felt as if I had spun the results, put a positive spin on the ugly, with a result that those staff who had already been angry, frustrated and disappointed now felt even more strongly that their voices were ignored, dismissed and unheard. Still taken aback, I tried to defend myself, arguing that it wasn’t spin but a matter of perspective. They weren’t having it, and they pushed back even harder than before. I was left reeling and confused. In my mind, I had presented the survey results with integrity. I couldn’t understand their hurt and angry responses. This was some years ago and I remember vividly, some days later, driving into work when a penny dropped suddenly. It occurred to me that, when a person describes a glass as half-empty, it’s not simply a matter of perspective but one of sentiment and emotional experience too. By presenting a glass as half-full, I had inadvertently failed to acknowledge and represent an authentic expression of how they were feeling. I returned to my colleagues and shared this somewhat embarrassingly-belated self-revelation – with which they wholeheartedly agreed. They accepted my apology with grace. You arrange to meet with a colleague and, on the afternoon of the appointment, she neither turns up nor cancels it. It can feel disappointing or frustrating, especially if you had spent ages preparing for it, or had rescheduled other things to make room for her in your diary. There may be, of course, all kinds of extenuating circumstances that had prevented her from arriving or letting you know. We could imagine, for instance, that her car had broken down on route, or that she had got stuck in traffic in an area with no mobile phone signal. She might have been held up in another meeting that overran and from which, for whatever reason, she had felt unable to excuse herself. Feelings of hurt or resentment can arise, however, if we allow ourselves to infer deeper meaning and significance from the no show. This can be especially so if it forms part of a wider and repeated pattern of experiences. Could it be, for instance, that her unexpected absence (again) is revealing a subtle and subliminal message such as, ‘Spending time on A is more important to me than spending time with you on B.’ Or, beneath that, ‘I believe my work on A is more important than your work on B’. Or deeper and worse still, perhaps, ‘I’m more important than you.’ The latter could well leave us feeling devalued and disrespected and, if unresolved, damage the relationship itself. I worked with one leader, Mike, who modelled remarkable countercultural behaviour in this respect. If Mike were in a meeting that looked like it may need to overrun, he would: (a) pause the meeting briefly (irrespective of how ‘senior’ or ‘important’ the person was whom he was with); (b) speak with whomever he was due to meet with next (irrespective of how ‘junior’ or ‘unimportant’ that person was); (c) check if it would be OK with them to start their meeting later or, if needed, to defer it; and (d) take personal responsibility to resolve any implications that may arise from that rescheduling. Needless to say, Mike’s integrity and respect earned him huge loyalty, admiration and trust. When have you seen great models of personal leadership? How do you deal with a no show? ‘Without transition, a change is just a rearrangement of the furniture.’ (William Bridges) Lean forward and look into the room. Listen in carefully to the conversation. An organisation has decided to move to smaller and cheaper office premises in order to reduce its overheads. It will mean agile working: a shift to hybrid working, hot-desking and staff lockers. It appoints a change team to oversee the move, and the team notices a range of responses from staff, from passive apathy to active dissent. It faces a growing concern about what it perceives as resistance to change. It tries hard with corporate communications to let staff know what will happen when and yet is increasingly bemused and anxious about the apparent lack of buy-in. The team invites me in as an external organisation development (OD) consultant to have a conversation with staff, an open exploration of issues and how to move things forward. Here’s a glimpse and summary, following initial rapport-building and relational-contracting to ensure a felt-sense of safety and trust in the room:

The change team had focused on practical changes (physical-transactional: what happens around us) and inadvertently failed to pay attention to corresponding human transitions (psychological-emotional: what happens within us). Notice the flow of the consultant conversation: from feeling, to meaning, to need, to solution. The style is invitational, enhancing the felt-sense of choice, influence and agency. Baskets are provided. Staff re-engage. The move goes ahead smoothly. [See also: Change leadership principles; Organisations don't exist] 'The optimism of the action is better than the pessimism of the thought.' (Greenpeace) Resilience is a common buzz word today, partly in response to the complex mental health challenges that individuals and communities face in a brittle, anxious, non-linear and incomprehensible (BANI) world. Who would have imagined 3 years ago, for instance, that Covid19 would strike or that Russia would invade Ukraine, with all the ramifications this has precipitated in our personal and collective lives? It can feel like too much time spent on the back foot, reacting to pressures that may appear from anywhere, without warning, from left field – rather than creating the positive future we hope for. A psychological, social and political risk is that people and societies develop a ‘Whatever’ attitude, an apathetic ‘What’s the point?’ mentality. After all, what is the point of investing our time, effort and other resources into something that could all get blown away again in a brief moment? A good friend worked in Liberia with a community that was trying to recover from the effects of a bloody civil war. They started to build schools, hospitals and other infrastructure and, just as things were beginning to look hopeful, a violent, armed militia swept through the area and burned everything to the ground. This can feel like an apocalyptic game of snakes and ladders. Take one step forward and, all of a sudden, back to square one again. A close friend in the Philippines befriended people in a very poor makeshift community, surviving at the side of a busy road in boxes and under tarpaulins. She worked hard to improve the quality of their lives, to ensure that they felt and experienced authentic love, care and support, and it started to have a dramatic human impact. Faces brightened and hopes were lifted. Then, out of nowhere, government trucks appeared and bulldozed that whole place to the ground. It could be tempting to give up. One coping mechanism is to focus on living just one moment, one day, at a time because, after all, 'Who can know what tomorrow will bring?' This may engender an element of peaceful acceptance, akin to that through mindfulness. It can also morph into a form of passive, deterministic fatalism: ‘We can’t change anything, so why try?’ Martin Luther King's response stands in stark contrast who, in the face of setbacks, advocated, ‘We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would more tragic than to stop at this point. We’ve got to see it through.’ Psychologically, both approaches could be regarded as survival strategies, as personal and social defences against anxiety. In a way, they are adaptive responses: ways of thinking, being and behaving that seek to create a greater sense of agency and control in the face of painful powerlessness. In the former case, a level of control is gained, paradoxically, through choosing to relinquish control. It's a letting-go rather than a clinging-on. In the latter, a fight-response (albeit a faith-fuelled, non-violent fight in the case of MLK), control is sought by changing the conditions that deprive of control. Each constitutes it's own way of responding to an external reality – and it’s out there as well as in here that the real and tangible challenges of resilience and transformation persist. The social, political and economic needs of the poorest, most vulnerable and oppressed people in the world don’t exist or disappear, depending simply on how we or they may perceive or feel about them. MLK’s call to action was radical: ‘We need to develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness. It’s no longer a question of what will happen to us if we get involved. It’s what will happen to them (and us) if we don’t?’ [See also: Resilient; When disaster strikes; Clash of realities] ‘It’s a question of what the relationship can bear.’ (Alison Bailie) You may have heard the old adage, the received wisdom that says, ‘Don’t try to run before you can walk.’ It normally refers to avoiding taking on complex tasks until we have mastered simpler ones. Yet the same principle can apply in relationships too. Think of leadership, teamworking, coaching or an action learning set; any relationship or web of relationships where an optimal balance of support and challenge is needed to achieve an important goal. Too much challenge, too early, and we can cause fracture and hurt. It takes time, patience and commitment to build understanding and trust. I like Stephen Covey’s insight that, ‘Trust grows when we take a risk and find ourselves supported.’ It’s an invitation to humility, vulnerability and courage. It sometimes calls for us to take the first step, to offer our own humanity with all our insecurities and frailties first, as a gift we hope the other party will hold tenderly. It's an invitation, too, for the receiver to respond with love. John, in the Bible, comments that, ‘Love takes away fear’. To love in the context of work isn’t something soft and sentimental as some cynics would have us believe. It’s an attitude and stance that reveals itself in tangible action. Reg Revans, founder of action learning, said, ‘Swap your difficulties, not your cleverness.’ A hidden subtext could read, ‘Respond to my fragility with love, and I will trust you.’ I joined one organisation as a new leader. On day 3, one of my team members led an all-staff event and, afterwards, she approached me anxiously for feedback. I asked firstly and warmly, with a smile, ‘What would you find most useful at this point in our relationship – affirmation or critique?’ She laughed, breathed a sigh of relief, and said, ‘To be honest, affirmation – I felt so nervous and hoped that, as my new boss, you would like how I had handled it!’ In this vein, psychologist John Bowlby emphasised the early need for and value of establishing a ‘secure base’: that is, key relationship(s) where a person feels loved and psychologically safe, and from which she or he can feel confident to explore in a spirit of curiosity, daring and freedom. It provides an existential foundation on which to build, and enables a person to invite and welcome stretching challenge without feeling defensive, threatened or bruised. How do you demonstrate love at work? What does it look like in practice? ‘Respect deeply the otherness of the other.’ (Richard Young) Navigating boundaries is a critical skill in coaching and action learning. Anne Katharine describes this phenomenon succinctly in the subtitle of her book: Where You End and I Begin (2000). Incorporate Psychology provides a useful explanation of different kinds of relational boundaries and what can go wrong if they become blurred, enmeshed or rigid. Khalil Gibran writes poetically on this same theme in The Prophet (1923): ‘Let there be spaces in your togetherness. Let the winds of the heavens dance between you…Even as the strings of the lute are alone though they quiver with the same music.’ In coaching and action learning, a variety of boundaries emerge that we need to pay attention to for this work to be effective. In a coaching relationship, the coach and client learn to navigate these including: their respective roles and responsibilities; their places and times of meetings; their accountabilities to any wider stakeholders; the scope and parameters of what each will focus on, and not; their agreements on what will remain confidential, or not, and to whom. In action learning, further boundaries include those between facilitator and group, and those between different group participants and roles. At deeper human levels, Gestalt psychology speaks of confluence, where a boundary is dissolved and the quality of healthy contact is compromised. The coach and client, or action learning presenter and peers, need to differentiate between, for instance: what’s simply here-and-now and what’s transference from the past; what’s the coach/peers’ stuff and what’s that of the client or presenter; what’s just about the client or presenter and what’s a parallel process of wider systemic or cultural influences. Managing boundaries is, we discover, a key dimension to success in these fields. ‘Anticipation is a gift. Anticipation is born of hope.’ (Steven L. Peck) Antoine de Saint-Exupéry tells the entrancing, magical story of a Little Prince from a faraway world who visits Earth and makes friends with a wild fox. When making preparations for his visits, the fox explains to the Prince earnestly: ‘If you come at four in the afternoon, I'll begin to be happy by three. The closer it gets to four, the happier I'll feel. By four I'll be excited and worried; I'll discover what it costs to be happy! But if you come at any old time, I'll never know when I should prepare my heart.’ The fox’s yearning resonates with a love poem by an unknown author: ‘There’s a moment between a glance and a kiss where the world stops for the briefest of times. And the only thing between us is the anticipation of your lips on mine. A moment so intense it hangs in the air as it pulls us closer. A moment so perfect that, when it comes to an end, we realize it’s only just beginning.’ It’s that not-quite-yet sense of an I-can-almost-touch-it moment; filled with tension, desire and anticipation. Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) draws on the visceral power of this anticipation phenomenon in its intriguing half-smile technique. An anxious person is invited to begin to start to smile – without allowing it to become a full smile – then to pause and hold the half-smile for a few…brief…moments. Subconsciously, we associate the physical sensation of an almost-smile with an anticipation of a positive mood and experience, and this can create a positive shift in how we feel. How well do you deal with waiting, with harnessing anticipation? [See also: Wait; and Instant] ‘It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.’ (Henry David Thoreau) Psychologist Albert Ellis, widely regarded as the founding father of what has today evolved into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, noticed that different people responded differently to what were, on the face of it, very similar situations. Previously, you might have heard, ‘Person X feels Y because Z happened’. It assumed a direct causal relationship between emotions and events. Ellis’ observations challenged this, proposing that something significant was missing in the equation. After all, if this assumption were true, we could expect that everyone should feel the same way in circumstance Z. Curious about this, Ellis concluded that the critical differentiating and influencing factor that lays between emotions and events is belief. It’s what we believe about the significance of an event that affects most how we feel in response to it. Here we have person A who hears news of a forthcoming redundancy with fear and trepidation. He believes it will have catastrophic financial consequences for himself and his family. Person B receives the news with positive excitement. She believes it will provide her with the opportunity she needs to pursue a new direction in her career. Drawing on this insight, organisational researchers Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal proposed that, in the workplace, what is most important may not be so much what happens per se, as what it means. The same change, for instance, could mean very different things to different people and groups, depending on the subconscious interpretive filters through which each perceives it. Such filters are created by a wide range of psychological, relational and cultural factors including: beliefs, values, experiences, hopes, fears and expectations. This begs an important question: how can we know? Hidden beliefs are often revealed implicitly in the language, metaphors and narratives that people use. To observe the latter in practice, notice who or what a person or group focuses their attention on and, conversely, who or what appears invisible to them. Listen carefully to how they construe a situation, themselves and others in relation to it. Inquire in a spirit of open exploration, ‘If we were to do X, what would it mean for you?’; ‘If we were to do X, what would you need?’ This is about listening, engagement and invitation. Attention to the human dimension can make all the difference. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed