|

‘Leadership is influence.’ (John C. Maxwell) It’s one thing to have insight. It’s another thing to exert influence on the basis of that insight. This is often a dilemma for leaders and professionals when seeking to influence change across dynamic, complex systems and relationships. After all, what if I can see something important, something that could make a significant difference, yet I can’t gain access to key decision-makers? Or what if, even if I can get access, they’re not willing to listen? What if people are so preoccupied by other issues that my message is drowned out by louder voices and I can’t achieve cut-through? Early in my career, I worked as OD lead in an international non-governmental organisation that was about to embark on radical change. I’d studied OD at university on a masters’ degree course and, based on that experience, could foresee critical risks in what the leadership was planning to do. I tried hard to get access to raise the red flags but, by the time I met with the leaders, it was too late. They had already fired the starting gun on their chosen programme. My concerns turned out to be well-founded, and the changes almost wrecked the organisation. I agonised for some time over why I’d been so ineffective at influencing their decisions. I learned some valuable lessons. Firstly, the view I held of my role – the contribution I could bring – was different to that of the leaders. I viewed myself as consultant whereas they viewed me as service provider. Secondly, the leaders had become so emotionally-invested in the change they had designed that they reacted defensively if challenged. They saw my well-meaning red flags as resistance rather than as a genuine desire to help. I would need to change my approach. Since then, I have practised building human-professional relationships with leaders and other stakeholders from the earliest opportunity. These relationships are built on two critical factors: firstly, respect for e.g. the studies, training, expertise and lived experience they bring to the table; and, secondly, empathy for e.g. the responsibilities, hopes, demands and expectations they face – both inside and outside of work. Against this backdrop, I’m able to pray, share my own insights and, where needed, advocate a change from an intention and base of support.

12 Comments

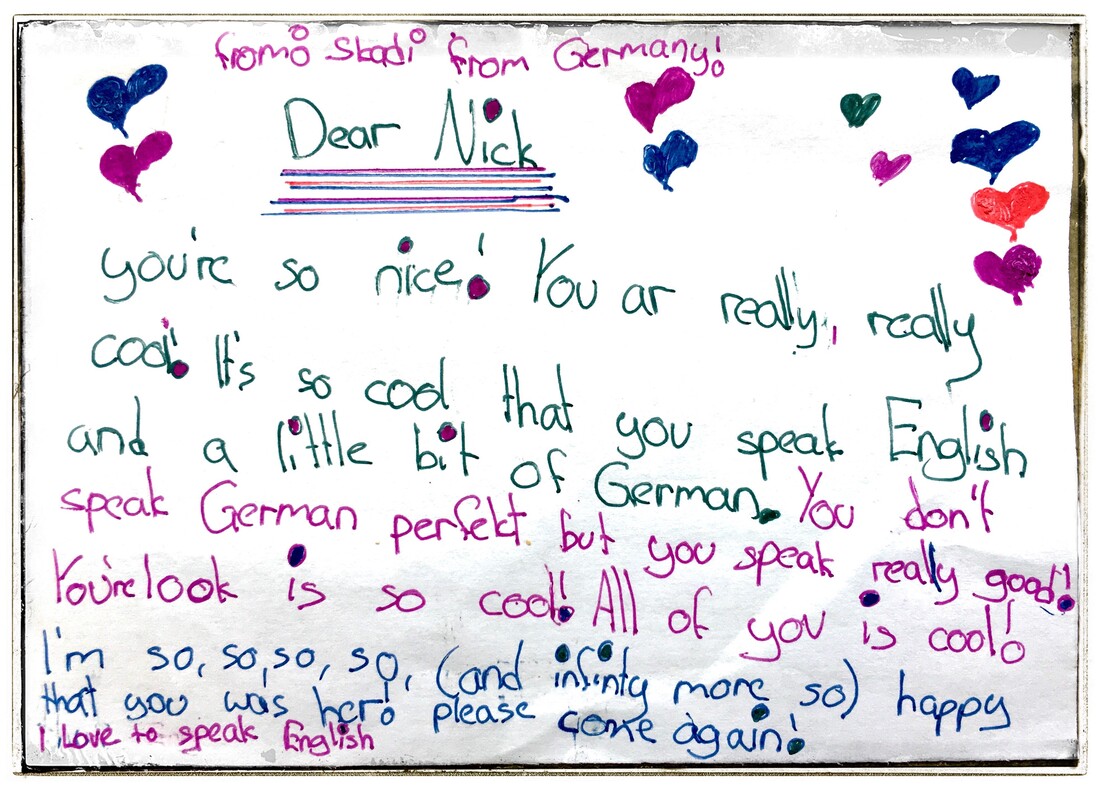

‘Empathy is about finding echoes of another person in yourself.’ (Mohsin Hamid) I remember Deryck Sheriffs, an inspiring South African lecturer, leading a seminar on, ‘Theology and Emotion in the Psalms’. He encouraged us, as students, to consider that there’s a critical distinction between propositional truth and pastoral response. Both are important. They are often intertwined. And we need to recognise which is which when reading a text. We must pay attention to e.g. genre; context; co-text; who is speaking; nature of relationship; underlying intention. I’ve noticed parallels in all kinds of communications over the years. Confusion and tension can arise when people speak and respond in conflicting relational modes. We could broaden this principle by distinguishing between a thinking and feeling orientation. If a person speaks in feeling mode and receives a thinking-mode response (or vice versa), they may feel hurt, unheard or frustrated. Here’s an example to illustrate this point. Person 1: ‘I wish the hospital staff would speak to me directly rather than through my carers.’ Person 2 (thinking mode): ‘The staff are very busy and it’s easiest for them to speak to your carers who can then explain everything to you.’ Person 3 (feeling mode): ‘I imagine that could feel quite isolating for you. What would you like us to do?’ The latter is grounded in empathy. ‘Empathy is the starting point for creating a community and taking action.’ (Max Carver) I had a long conversation with a Kurdish-Iranian man recently about his experience as a refugee in the UK and the ongoing wait for news that his wife will be allowed to join him here. With a warm smile of anticipated relief, he shared his hopes of building a new life in this country where he and his wife can finally feel safe and free. Yet then he touched his heart with his hand and his face shifted to a pained expression. He shared his sadness that he can never feel truly happy and at peace, knowing the oppression that his family, friends and neighbours are still living under in his home country. I was moved by his empathy and, at the same time, impressed by his stance that under such difficult and protracted life circumstances, he had not become so focused on his own situation that he had lost sight of others. It is, after all, a human risk that, when faced with challenges such as high anxiety and stress, our survival instinct can take over and turn us in on ourselves, absorbing us with our own needs and interests – a bit like when the body reacts to an external shock or threat by diverting its resources inwards to protect its vital organs. It’s a form of defensive flight to save ourselves first. How do you hold onto empathy...to love...when natural instinct may push or pull you to withdraw? 'There is a universal human tendency to conceive of all things as like ourselves.' (David Hume) In the ground-breaking, futuristic film ‘Her’ (2014), actor Joaquin Phoenix played the part of a man who falls in love with an artificially intelligent (AI) virtual assistant. The AI, whose voice was played by actress Scarlett Johansson, was capable of deep learning. It, or we could say ‘she’, spoke, responded and interacted with the protagonist in ways that we could imagine of a real woman in an increasingly loving relationship – and all via a voice. The movie played with the social-psychological possibilities and limits of the potential inter-relationship between humans and technology. In the next year another movie, ‘Ex Machina’ (2015), saw Domhnall Gleeson playing the role of a computer programmer who encounters an AI robot, this time in the physical form of a beautiful woman played by Alicia Vikander. Gleeson is invited by a tech entrepreneur to test (a) whether she’s capable of genuine consciousness and (b) whether he can relate to her as ‘human’, even though he knows she is artificial. As the plot plays out, the AI skilfully seduces and manipulates the programmer, with apocalyptic implications as the AI plays out the relational game and wins. One of the striking features of both dramas is the human ability to project our human qualities onto other people or things, in this case the AIs, in ways similar to those in which we may, say, attribute human qualities to a dog – and then relate to it as if it were in some way human. It’s a subconscious phenomenon, a blurring of the boundaries between reality and fantasy. We can know something to be true at a rational-cognitive level and, yet, still feel and behave as if a different reality were true. It’s like believing what we want to believe, when it fulfils a human need to do so. ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. No, not platypus – that’s a duck-billed, beaver-tailed, otter-footed, egg-laying aquatic creature native to Australia. ‘Don’t worry – be happy.’ Now, that’s a platitude. It’s a superficial cliché that rolls too easily off the tongue, without thinking, and presents itself as truth. It’s the kind of thing you may well hear from well-meaning, secure, content-with-life people; yet lacks empathy, depth or genuine appreciation of a person, situation or struggle. Now you may already be thinking, ‘I wouldn’t worry about that if I were you.’ Oops. Ding! Platitude. Here’s the thing: I’m not you; I might not worry about it if I were you; you might worry about it too if you were me. Furthermore, I’m a human being, not a robot. I don’t have an on-off switch for worry, or for happiness, although I sometimes wish I did. A platitude creates the sense of saying something useful…without actually saying something useful. So, what’s the antidote? How can I avoid inadvertently slipping into platitude-speak? 1: Listen. Don’t speak. Zip it. Resist the temptation to fill the space, to apply a fix without having heard. 2: Empathise. Feel the feeling, the emotional tone, the tremor, the resonance that lays behind the words. 3: Understand. ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘What do you need?’ Great questions, powerful reach. 4: Offer. Share your wisdom – if called for. Make it real. At just 5 feet (152 cm) tall, this Filipina presents an imposing stature. She went out this week to provide emergency food and modest cash gifts to some of the poorest people in the Philippines, those who live at the roadside on zero income owing to the Covid-19 lockdown. She herself is very poor yet determined to share what she has for the benefit of strangers in need. She prays to Jesus, dons a face mask and heads out fearlessly. One family revealed they had barely survived until she arrived. They had been living on just boiled water with a little sugar stirred into it. No rice, and little hope. One group surrounded her when she at first appeared. Some men grabbed the bags of rice that she carried with her, skulking away in an attempt to avoid being caught. At that, she lifted her mask and yelled assertively: ‘Bring that back now, or I leave here with everything I came with.’ Slowly…the stealthy thieves reappeared, with guilty expressions on their faces now, and handed them back. She explained, ‘We are poor, but this is no way to conduct ourselves. We need to learn to share what we have, like Jesus.’ She then held out the sacks and cash, and every family went home with something real. I asked her if she had felt nervous, to be confronted and robbed like that in broad daylight. She was, after all, alone among strangers and anything could have happened. She said no, she wasn’t afraid, because she had prayed hard before setting out. ‘I know what it is to be poor, and I have lived my entire life among the poor.’ I reflected on how I might have acted defensively in response, annoyed by their attitude and fearful for my own safety. By contrast, she showed courage, empathy, faith and love. Question: When have you been at your most fearless? What made the difference for you? ‘We need to talk.’ 4 short words that can send a chill running down the spine. Perhaps it taps into being caught out as a child. That look from a parent or teacher when we know we’re in trouble. My wife called me into a room. ‘I want a divorce.’ 4 short, sharp words that created that same cold shiver. The room starts to spin, pulse races, breathing feels difficult. Fight, flight, freeze. Shock.

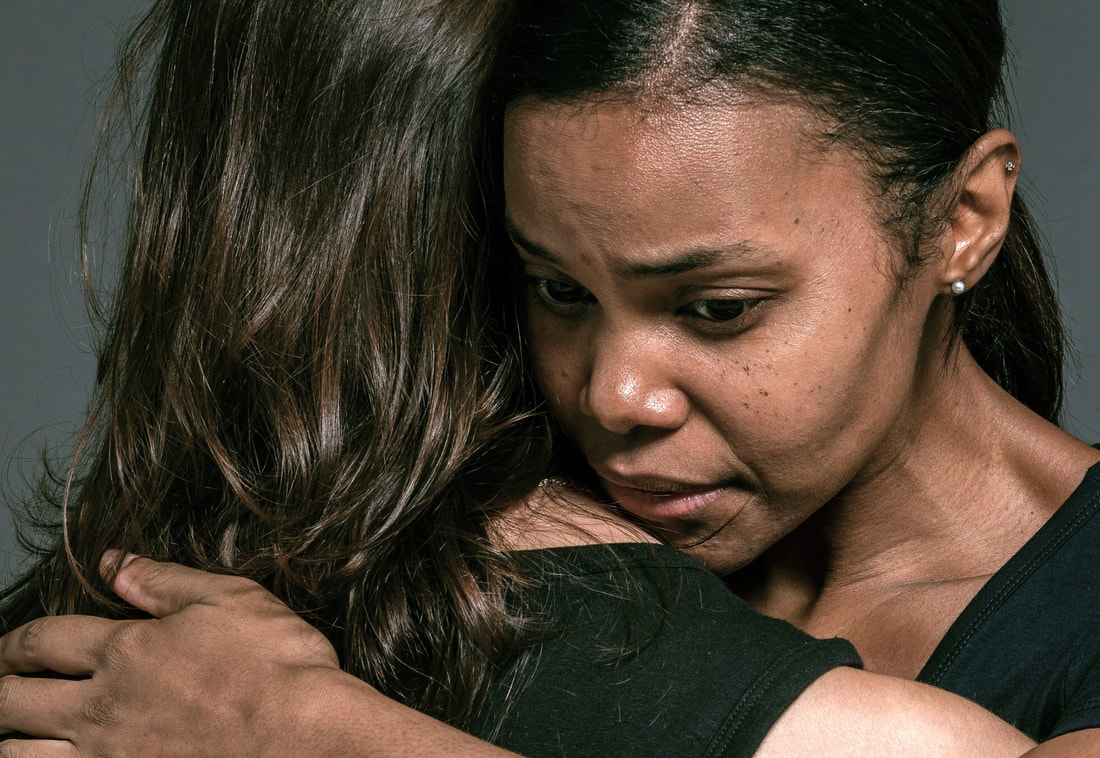

I want to run but my feet feel glued to the ground. It’s like I can’t move. Words clutter my brain and I speak but it all comes out clumsily, awkwardly, wrong. I feel angry and sad and understanding and confused. My wife’s face is telling its own story but I can’t read it. She looks absolutely the same and yet completely different. This is the woman I’ve known for 25 years. Scared – intimate strangers. Life change really can feel like this, especially unexpected, out-of-the-blue change. It can send us reeling, a psychological, emotional and physical jolt. Debilitating and disorientating, dizzying in its effects. It draws deep spiritual and existential questions into sharp focus. ‘Why is this happening to me?’, ‘How could we have got here?’ It feels like grasping at mist, straining to take hold of God. Perhaps you’re a leader, leading people through organisational change. Perhaps you’re a coach, therapist or trainer, working with people through transition. Here are 4 words of advice in such situations: Empathy: give people cathartic space to feel; Listen: create opportunities for people to talk; Patience: allow time for people to process what they're going through; Speak: 4 words – ‘I am with you.’ When teams are under pressure, e.g. dealing with critical issues, sensitive topics or working to tight deadlines, tensions can emerge that lead to conversations getting stuck. Stuck-ness between two or more people most commonly occurs when at least one party’s underlying needs are not being met, or a goal that is important to them feels blocked.

The most obvious signs or stuck-ness are conversations that feel deadlocked, ping-pong back and forth without making progress or go round and round in circles. Both parties may state and restate their views or positions, wishing the other would really hear. If unresolved, responses may include anger/frustration (fight) or disengagement/withdrawal (flight). If such situations occur, a simple four step process can make a positive difference, releasing the stuck-ness to move things forward. It can feel hard to do in practice, however, if caught up in the drama and the tense feelings that ensue! I’ve found that jotting down questions as an aide memoire can help, especially if stuck-ness is a repeating pattern. 1. Observation. (‘What’s going on?’). This stage involves metaphorically (or literally) stepping back from the interaction to notice and comment non-judgementally on what’s happening. E.g. ‘We’re both stating our positions but seem a bit stuck’. ‘We seem to be talking at cross purposes.’ 2. Awareness. (‘What’s going on for me?’). This stage involves tuning into my own experience, owning and articulating it, without projecting onto the other person. E.g. ‘I feel frustrated’. ‘I’m starting to feel defensive.’ ‘I’m struggling to understand where you are coming from.’ ‘I’m feeling unheard.’ 3. Inquiry. (‘What’s going on for you?’). This stage involves inquiring of the other person in an open spirit, with a genuine, empathetic, desire to hear. E.g. ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘What are you wanting that you are not receiving?’ ‘What’s important to you in this?’ ‘What do you want me to hear?’ 4. Action. ('What will move us forward?’) This stage involves making requests or suggestions that will help move the conversation forward together. E.g. ‘This is where I would like to get to…’ ‘It would help me if you would be willing to…’. ‘What do you need from me?’ ‘How about if we try…’ Shifting the focus of a conversation from content to dynamics in this way can create opportunity to surface different felt priorities, perspectives or experiences that otherwise remain hidden. It can allow a breathing space, an opportunity to re-establish contact with each other. It can build understanding, develop trust and accelerate the process of achieving results. I took my mountain bike for repairs last week after pretty much wrecking it off road. In the same week, I was invited to lead a session on ‘use of self’ in coaching. I was struck by the contrast in what makes a cycle mechanic effective and what makes the difference in coaching. The bike technician brings knowledge and skill and mechanical tools. When I act as coach I bring knowledge and skills too - but the principal tool is my self.

Who and how I am can have a profound impact on the client. This is because the relationship between the coach and client is a dynamically complex system. My values, mood, intuition, how I behave in the moment…can all influence the relationship and the other person. It works the other way too. I meet the client as a fellow human being and we affect each other. Noticing and working with with these effects and dynamics can be revealing and developmental. One way of thinking about a coaching relationship is as a process with four phases: encounter, awareness, hypothesis and intervention. These phases aren’t completely separate in practice and don’t necessarily take place in linear order. However, it can provide a simple and useful conceptual model to work from. I’ll explain each of the four phases below, along with key questions they aim to address, and offer some sample phrases. At the encounter phase, the coach and client meet and the key question is, ‘What is the quality of contact between us?’ The coach will focus on being mentally and emotionally present to the client…really being there. He or she will pay particular attention to empathy and rapport, listening and hearing the client and, possibly, mirroring the client’s posture, gestures and language. The coach will also engage in contracting, e.g. ‘What would you like us to focus on?’, ‘What would a great outcome look and feel like for you?’, ‘How would you like us to do this?’ (If you saw the BBC Horizon documentary on placebos last week, the notion of how a coach’s behaviour can impact on the client’s development or well-being will feel familiar. In the TV programme, a doctor prescribed the same ‘medication’ to two groups of patients experiencing the same physical condition. The group he behaved towards with warmth and kindness had a higher recovery rate than the group he treated with clinical detachment). At the awareness phase, the coach pays attention to observing what he or she is experiencing whilst encountering the client. The key question is, ‘What am I noticing?’ The coach will pay special attention to e.g. what he or she sees or hears, what he or she is thinking, what pictures come to mind, what he or she is feeling. The coach may then reflect it back as a simple observation, e.g. ‘I noticed the smile on your face and how animated you looked as you described it.’ ‘As you were speaking, I had an image of carrying a heavy weight…is that how it feels for you?’ ‘I can’t feel anything...do you (or others) know how you are feeling?’ (Some schools, e.g. Gestalt or person-centred, view this type of reflecting or mirroring as one of the most important coaching interventions. It can raise awareness in the client and precipitate action or change without the coach or client needing to engage in analysis or sense-making. There are resonances in solutions-focused coaching too where practitioners comment that a person doesn’t need to understand the cause of a problem to resolve it). At the hypothesis stage, the coach seeks to understand or make sense of what is happening. The key question is, ‘What could it mean?’ The coach will reflect on his or her own experience, the client’s experience and the dynamic between them. The coach will try to discern and distinguish between his or her own ‘stuff’ and that of the client, or what may be emerging as insight into the client’s wider system (e.g. family, team or organisation). The coach may pose tentative reflections, e.g. ‘I wonder if…’, ‘This pattern could indicate…’, ‘I am feeling confused because the situation itself is confusing.’ (Some schools, e.g. psychodynamic or transactional analysis, view this type of analysis or sense-making as one of the most important coaching interventions. According to these approaches, the coach brings expert value to the relationship by offering an explanation or interpretation of what’s going on in such a way that enables the client to better understand his or he own self or situation and, thereby, ways to deal with it). At the intervention phase, the coach will decide how to act in order to help the client move forward. Although the other three phases represent interventions in their own right, this phase is about taking deliberate actions that aim to make a significant shift in e.g. the client’s insight, perspective, motivation, decisions or behaviour. The interventions could take a number of forms, e.g. silence, reflecting back, summarising, role playing or experimentation. Throughout this four-phase process, the coach may use ‘self’ in a number of different ways. In the first phase, the coach tunes empathetically into the client’s hopes and concerns, establishing relationship. In the second, the coach observes the client and notices how interacting with the client impacts on him or herself. The coach may reflect this back to the client as an intervention, or hold it as a basis for his or her own hypothesising and sense-making. In the third, the client uses learned knowledge and expertise to create understanding. In the fourth, the coach presents silence, questions or comments that precipitate movement. In schools such as Gestalt, the coach may use him or herself physically, e.g. by mirroring the client’s physical posture or movement or acting out scenarios with the client to see what emerges. In all areas of coaching practice, the self is a gift to be used well and developed continually. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed