|

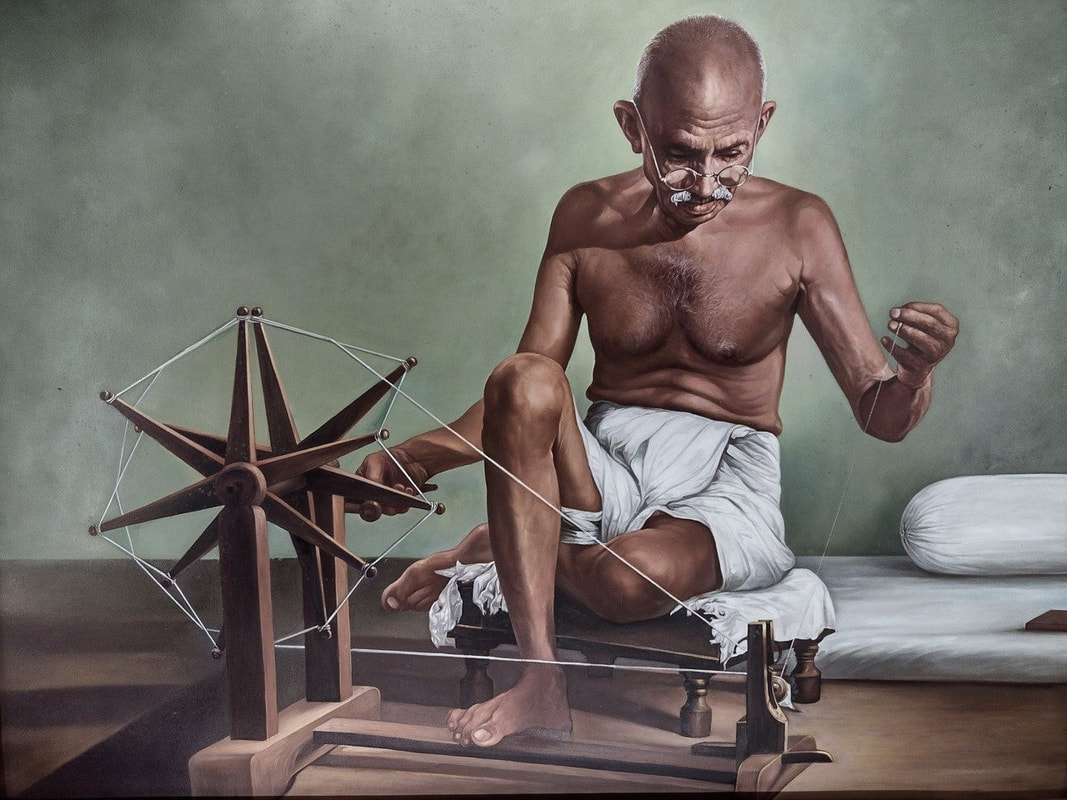

‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life?

20 Comments

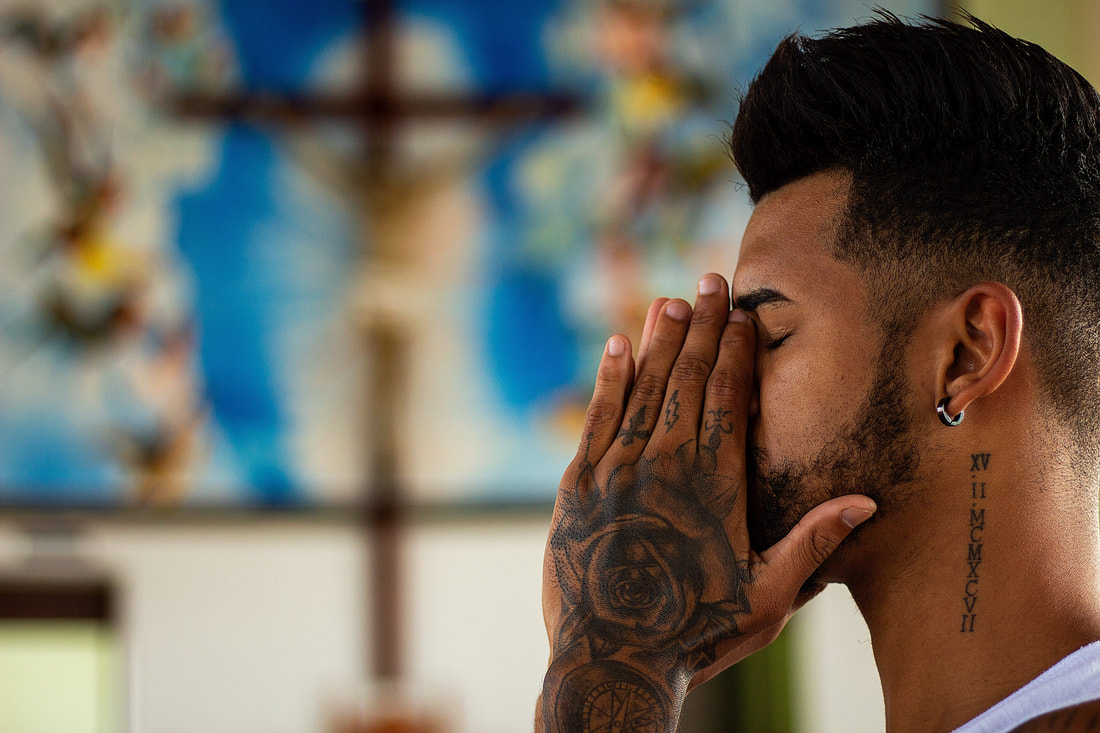

‘Coincidence doesn't happen a third time.’ (Osamu Tezuka) I arrived in the Netherlands on Saturday, aiming to orientate myself briefly to this new country before working with an INGO team there on Monday. When I stepped into my hotel room, however, it smelt damp and sweaty. Trying not to breathe, I opened the windows to an icy blast and decided to go for a walk while the fresh air did its work. Not far away, I noticed a church building so walked over to have a glance at its meeting times. As I did so, I looked up and saw a cross in the sky, a misty symbol painted momentarily on blue canvas by vapour trails. It felt significant, but I didn’t know why. The next day, the church was full when I arrived and I sat quietly in the midst, happily surprised by how much Dutch I could understand. (I can speak German, but this was my first time to read this new language). At the end, a woman kindly introduced herself to me. On learning that I am English, she explained that the church is recovering from an intensely painful internal conflict. The pastor had spoken on a need to look to God. I showed her the photo I had taken the day before – a symbol of suffering and hope – and she started to weep. ‘God brought you here to us this morning, Nick.’ Another woman now introduced herself, explained briefly that she had worked internationally in medical mission, and invited me to a special meeting that afternoon for asylum seekers and refugees. ‘How could she possibly have known anything about my life and work?’ I asked myself, a total stranger. The guest speaker that day was a visitor from Algeria and, serendipitously, works for the same organisation I was about to work with the following day... as does a man who randomly found himself sitting beside me in a hall full of people. Was this all coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide. ‘Try to be a rainbow in someone’s cloud.’ (Maya Angelou) I can’t create a rainbow. I can only witness its radiant beauty. A rainbow itself is created by white light, refracted as it strikes droplets of water in the air, often seen most vividly during or after rainfall. Some of the most stunning I’ve seen have been in Scotland where sunshine and rain are common together, with bright-coloured rainbows emerging like curvaceous, prismatic streamers in their midst. The Bible depicts rainbows as signs of spiritual-existential promise, of hope, initiated by God. Again, this isn't something I can make happen. I can only witness it, experience it, be awestruck by it. It’s something, or rather Someone, who clings to me amidst the violent storms, raging winds and torrential downpours of my life. Often, quite literally, this has been the only reason why I'm still alive today. Sometimes, I only perceive or discern the traces of a rainbow after the event. It’s like a mysterious pattern that appears, by faith, and is only visible from a distance. I went to theological school for 3 years. Inexplicably, my fees and living expenses were fully-paid. I remember, however, sitting on the side of my bed, alone and in near-despair. Studying God like studying physics felt like a travesty. Years later, the hidden seeds sown through that experience gradually came to fruition. I can now see the deep wisdom in that youthful decision, that strange prompt of divine opportunity that had felt so hard for me at the time. It was a period that had included a broken engagement, a snapped shin bone, tests for throat cancer and many other painful trials. Yet still, somehow...a rainbow appeared. ‘The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious.’ (Albert Einstein) ‘According to these blood test results’, said the consultant, ‘you are dead.’ He stood at the end of my hospital bed scratching his head. ‘Clearly you’re not dead’, he continued, ‘or we wouldn’t be having this conversation. There must be an error.’ He asked a nurse to take fresh bloods and to send them off urgently to the lab. Later that day with a new report in his hand, he looked even more confused. ‘The results are the same. This is impossible.’ We looked at each other. I didn’t know what to say. I had been experiencing severe pain and blackouts, often falling unconscious without warning, and had no idea why. So now the consultant sent me for a CT scan using a radioactive dye to get a clear scan result. The dye triggered an anaphylactic reaction which nearly killed me. An attentive passing nurse pushed an oxygen mask on my face, turned it up full and ran to find a crash kit. Unfortunately, someone had removed the adrenaline jab and hadn’t replaced it. I was within 2 minutes of death. By divine coincidence, that same day my ex-wife left me and took our 2 daughters with her: some would say that when it rains, it pours… I can’t explain these strange medical mysteries yet I can, by faith, trace a rainbow through the rain. The hospital drama that distracted me from difficult home events; the nurse who recognised and responded to my crisis; the availability of specialist medical facilities and drugs to save my life; the compassion of my brother and his family who supported me throughout. When have you experienced the mysterious? ‘It’s the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science.’ (Albert Einstein) ‘At such moments we don't choose silence...but fall silent.’ (Philip Simmons) As 2024 opened, I found myself yearning for silence, a sacred space to sit quietly and alone with my face turned unequivocally towards God. I found such a place in Alnmouth, a Franciscan retreat centre in the North East of England. Its spirituality focuses on Jesus and the poor and that matters deeply to me too. I had first found Jesus through a close friend who went on to become a Franciscan so this felt like a familiar place, like returning home after a long journey away. I packed a case and went. The days started early and ended late with a time of silence or spoken liturgy in a simple candle-lit chapel. As I sat or stood listening to the devout Franciscans chanting words slowly and meditatively from the Bible, my attention was drawn to a stark representation of Jesus on a cross at the front, straining to look upwards to his Father. I felt hurt, angry and confused by his suffering and, at the same time, intensely frustrated by my own weak faith and what the Bible calls sinfulness. He deserves better. As I sat in the deep silence that followed, I recalled some words from Iain Matthew (The Impact of God): ‘Someone is there – you notice out of the corner of your eye – Someone is there looking at you...and has been for some time. You realise your whole Christian life is an effect, the effect of a God who is constantly gazing at you – whose eyes anticipate, penetrate and elicit beauty.’ It isn’t about me. It's about God's expression of amazing divine love that holds the power to transform everything. ‘Tomorrow is the first blank page of a 365-page book. Write a good one.’ (Brad Paisley) It was my first time at a Greenbelt Festival in the UK and I remember wearing simple sandals made from recycled car tyres and a leather headband to keep my hair out of my face. I painted a cross on my forehead, carried a bamboo flute (which I couldn’t play) and walked with friends amidst the crowds towards the centre stage. Radical social activist, Jim Wallis, was the keynote and he spoke passionately about a place in the Bible where Jesus reveals who and what matters to him in this world. I felt spellbound. It resonated deeply with my own spiritual convictions – nothing to do with religious moralising and everything to do with a vision, an ethic, a possibility, a relationship. ‘I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.’ In this narrative, those to whom Jesus is speaking were puzzled and asked when they had done this. ‘Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ Jesus was sharing with astonishing clarity the lens through which he views our priorities and relationships. The way we treat others in need – the poor, the outsider, the sick, the oppressed – is the way that Jesus considers we reflect and treat him. Please God, as we enter this new year: shine your light of love, truth and hope through my life with ever-increasing brightness. ‘Learn from history, maintain your mystery, take your victory.’ (Amit Kalantri) Sometimes, we need to look back to look forward and the New Year can present us with a special opportunity to do just that. We could think of this as analogous to an annual performance review, where we pause for a moment and take stock of progress and learning so far before moving on. At a personal level, I’ve been thinking and writing quite a lot recently about Kairos moments in my own life that have, in retrospect, often proved pivotal. These experiences carry a spiritual quality and significance for me that both transcend the temporal and reveal a deeper sense of meaning. An instance comes to mind when, 3 days into a leadership role in a new organisation (to me), my line-manager called me into his office to confess, in deep disappointment, that funding for (a) a new leadership coaching programme and (b) a new management development programme, both of which were to lay in my area of responsibility, had been slashed as part of broader financial cuts. He apologised that, as a consequence, these flagship initiatives could no longer go ahead. I could see a look of anxiety on his face wondering, I imagine, how I might react to this bombshell news. I prayed silently then responded in a spirit of curiosity that, if these initiatives were priority, I’d just need to find a different way to achieve them. I thanked him for being open, prayed, then placed an invitation on LinkedIn, asking if anyone would like to offer pro bono coaching support for leaders in a national UK charity. Within 10 days, 180+ people had responded to offer their services. I also prayed and asked around if anyone would be willing to run a pro bono management development programme. A prestigious agency responded and ran an annual programme for us for 4 years running. I’m reflecting on why this experience came to mind for me now. It happened 10 years ago yet still feels so profoundly resonant as we approach the New Year. The first lesson for me is that it’s not all about me. God is capable of doing far more than I can ask or imagine. The second is the rich relational resourcefulness of networks, the kindness of so many people who are willing to offer themselves in heartfelt service when offered meaningful opportunities to do so. The third is the power of invitation, not expectation, that draws people freely into co-creative partnership to do something amazing. Today is a dark day. The wind and rain outside reflect the deep, dark feeling inside. One of the women who featured in small things, the video, in July…has died. She didn’t die from an accident or a serious illness. She died because she is poor. She loved to help others and brought joy to the lives of those who live on the far edge of hope. That is her tribute – her simple, beautiful legacy. With no shoes to wear, she got a small cut on her foot. Not wanting to burden her family with the cost of help that they too could ill afford, she hid it from them and didn't say anything. She wrapped a makeshift bandage around it, but couldn’t keep it clean. With untreated diabetes, no sanitation and being too poor to access doctors, hospitals or medication, the wound festered and killed her. I hate that the poor are so vulnerable. And I’m trying to remind myself: we can be hope. ‘Coincidences are God’s way of remaining anonymous.’ (Albert Einstein) If you ever read David Wilkerson’s The Cross and the Switchblade, you’ll get this. Two weeks ago, a song came to mind that I had written then recorded as a duet with a Christian friend, Maggie, some 37 years ago. Life moved on and Maggie and I hadn’t spoken since. In fact, I had completely forgotten ever having written and recorded that and other songs. Wondering what this mysterious prompt might mean, I rummaged through a box of old items and, to my immense relief, found a cassette with a hand-written label, ‘Niksongs’, on the side. Filled with excitement, I searched online to find some way of copying the cassette to USB so that I could listen to it on my laptop. I found a device designed for that purpose and tried it in eager anticipation but, unfortunately, it didn’t work. Whilst pondering today what to do next, my phone pinged. A message from…Maggie. What?!! Living in Sri Lanka now, she had just found a copy of that very same cassette and was in process of working out how to convert it too – and that was her cue to contact me now. Pure coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide. ‘If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine.’ (Ernesto Che Guevara) It looked like a scene from Dante’s inferno. Students from a very poor barangay (community) in the Philippines arrived home this week… Delete, rewind: arrived at where their makeshift homes had been until this week, to see them engulfed in a blaze of fire and billowing with thick, black smoke. The poor have no land rights, no insurance and no savings to fall back on. For a moment, it felt like their lives, as well as their homes, had gone up in flames. On hearing of this, one of their tutors, Jasmin, raced to provide them with emergency relief. She offered them a safe place to sleep in her own home, yet they refused – preferring to stay with their families in the midst of the charred and burned-out remains. On receiving her gift of food supplies, they immediately shared it with their extended families and with their neighbours who had lost all too. The next day, their fellow students rallied around in support. Rumours spread quickly that corrupt officials were behind the disaster as a way of driving the poor off the land to sell it to rich property developers – in exchange for a substantial bribe. Being sited at a prime seaside location, and being told immediately by the local Mayor that they would not be allowed to return, added sinister credence to these fears. The barangay residents have no access to justice, yet say they have Jesus as their advocate and hope. Life is hard-edged for the poor. We, too, can be hope. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed