|

‘Learn from history, maintain your mystery, take your victory.’ (Amit Kalantri) Sometimes, we need to look back to look forward and the New Year can present us with a special opportunity to do just that. We could think of this as analogous to an annual performance review, where we pause for a moment and take stock of progress and learning so far before moving on. At a personal level, I’ve been thinking and writing quite a lot recently about Kairos moments in my own life that have, in retrospect, often proved pivotal. These experiences carry a spiritual quality and significance for me that both transcend the temporal and reveal a deeper sense of meaning. An instance comes to mind when, 3 days into a leadership role in a new organisation (to me), my line-manager called me into his office to confess, in deep disappointment, that funding for (a) a new leadership coaching programme and (b) a new management development programme, both of which were to lay in my area of responsibility, had been slashed as part of broader financial cuts. He apologised that, as a consequence, these flagship initiatives could no longer go ahead. I could see a look of anxiety on his face wondering, I imagine, how I might react to this bombshell news. I prayed silently then responded in a spirit of curiosity that, if these initiatives were priority, I’d just need to find a different way to achieve them. I thanked him for being open, prayed, then placed an invitation on LinkedIn, asking if anyone would like to offer pro bono coaching support for leaders in a national UK charity. Within 10 days, 180+ people had responded to offer their services. I also prayed and asked around if anyone would be willing to run a pro bono management development programme. A prestigious agency responded and ran an annual programme for us for 4 years running. I’m reflecting on why this experience came to mind for me now. It happened 10 years ago yet still feels so profoundly resonant as we approach the New Year. The first lesson for me is that it’s not all about me. God is capable of doing far more than I can ask or imagine. The second is the rich relational resourcefulness of networks, the kindness of so many people who are willing to offer themselves in heartfelt service when offered meaningful opportunities to do so. The third is the power of invitation, not expectation, that draws people freely into co-creative partnership to do something amazing.

14 Comments

‘There’s nothing more dangerous than a resourceful idiot.’ (Scott Adams) 15 minutes before I was due to lead an online change leadership workshop in Germany, I stepped outside briefly for a breath of fresh air. I wanted to clear my head, focus and pray. Then…oh no, I heard a gentle click behind me and discovered, to my alarm, that I couldn’t open the door without a key. It hung tantalisingly on the inside and I could see my mobile phone staring at me blankly from the table. Aha, I thought. I will ask my hosts to let me in. Oh, they were out. Mild feelings of panic rising, I rushed to a neighbour. Thank God they were in, could understand my Englisch-Deutsch, had the hosts’ number and could call. Now, with just 2 minutes to go, my host appeared and saved the day. It was a timely reminder that sudden change can come from anywhere, unexpectedly and often from left field. It was also a helpful reminder that leadership, resilience and agency aren’t simply inward, intra-personal qualities or strengths. Our ability to handle the impacts of changes and transitions often emerges from an outward-facing resourcefulness, looking outside of ourselves openly (and, for me, prayerfully) for people and-or other resources who can co-create and co-enable a solution with us…or – if no solution is possible – sit with us in the midst of discomfort, disappointment or pain. 'Don't be still. One of the most common mistakes when change is upon us is to take enormous amounts to time to run analysis and come up with various routes to be followed. Sitting still in moving waters will only lead to a ship becoming adrift, with no indication of where it will end up or whether it will sink. If adjusting the course is needed, the leader should do it quickly and without hesitation.' (Raluca Cristescu)

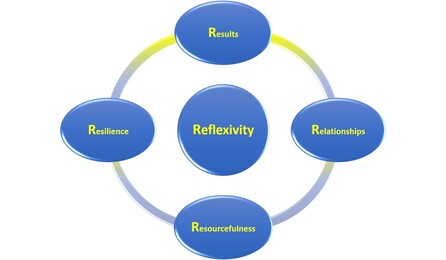

The start of this new year has felt like a very rough ride for some people. I’ve been working alongside humanitarian disaster management experts in and from a wide range of countries, trying to make a difference for those who are poorest and most vulnerable in the world. In some places, wave after wave of devastating impacts have hit hard and fast, ranging from drought, crop failure and swarms of locusts to military conflict and deep civil unrest – all with the ongoing Covid-19 crisis overlaid on top. A close friend in the Philippines spent today with her children, praying earnestly and wrapping what few possessions they have in plastic bags in preparation for the roof of their fragile boarding house being torn off by an impending typhoon. Others I’ve been supporting have been grafting long hours, trying to help people and communities recover from the effects of war. The power fluctuates on and off, as does the wifi signal, making online communication difficult – yet I, we, they, persevere. My first direct experience of disaster response was some years ago during the Kosovo crisis. I travelled with a team across Spain, France, Italy and Albania to take emergency logistical supplies to refugee camps on the frontline border with Serbia. Our vehicles were fitted with spare tyres, satellite communications equipment and ballistic blankets in case we drove over land mines. I remember vividly the ‘No weapons on board’ symbols on our windows – signalling, I hoped, ‘Please don’t shoot us.’ We encountered challenge-after-challenge on route. At times, it felt as if everything was against us. As military helicopters flew overhead in impressive formation, we meanwhile were often stuck firmly on the ground, mired in red tape or the insidious effects of blatant corruption. It was a rapid learning experience for me, seeing how my seasoned disaster response colleagues handled this. It was my first exposure to adaptive leadership in a crisis too – out in the field, not inside an organisation. It went something like this: 1. Hold tightly to your goals and values but loosely to your plans. If you expect everything to go smoothly, you will get disheartened and frustrated. 2. Treat every roadblock as a new reality. It’s not the end of the road, it’s another challenge to navigate. 3. Think quickly and tactically. Lateral thinking will prove more useful than strategic planning. 4. When faced with an obstacle, take a decision and act. Don't stop, keep moving. 5. Pray – God can do more than you can do. This kind of activist-pragmatist outlook, behaviour and stance draws on and develops creativity, innovation, resourcefulness and resilience. It’s a way in which the poorest and most vulnerable people and communities learn to survive and thrive too. When a life situation is too painful, turbulent or dynamically-complex to understand, predict or control, a focus on the here-and-now can be the most meaningful choice. Even small steps can engender and evoke a real sense of agency, hope and change. My work now includes coaching, mentoring, facilitating and training of humanitarian field workers in action learning: a here-and-now, real-time methodology to stimulate adaptive leadership and learning in the midst of action. It’s an experimental pilot initiative with a global network of humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and a team of action learning specialists. When have you developed or used adaptive leadership in a crisis? How did you do it? What difference did it make? Accidents happen. How do you respond to incidents that knock your carefully-made plans sideways? I felt a bit nervous as I entered the office and, then, decidedly embarrassed as I accidentally tipped a hot cup of tea down my smart white shirt. The client looked bemused, as if trying to stifle a smile, before racing out of the room to return with a bright yellow t-shirt. Kind man. Not to be out-done by this, my brother went to a formal, tense business meeting with a client. As he approached their office, a car mounted the pavement and hit him, sending him flying into a wet, muddy gutter. His case burst open and his papers went everywhere. It almost broke his thigh but it also broke the ice. It’s funny how, sometimes, when things go wrong – paradoxically – it makes things go right. In both cases, what felt like a complete disaster in the moment turned out to be the very thing that enabled a different type of contact, a positive bridge of human empathy and relationship and a better outcome. An emotional experience of humour or relief melted the rational, technical barriers that could otherwise have proved more difficult to navigate. Yet how many of us would welcome such ‘accidents’ when they arise, or see only how they wreck our plans, expectations or delicate egos? It calls for a different kind of awareness, expectation and stance in the world. It means being open to possibilities, opportunities and potential in whatever happens. It’s far less about being planned and more about being prepared. It’s consistent with Professor Richard Wiseman’s view of what makes some people (apparently) ‘luckier’ than others (https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06t5w4d). In coaching, we call this developing a client’s resource-fulness. Often, it entails enabling a person to approach the world, work and relationships with open hands, mind and heart; faith, hope and love. So – how do you respond to serendipitous ‘accidents’? How do you build clients’ resourcefulness? How can I help you to be more resourceful? Get in touch! [email protected] People sometimes ask if I have a guiding framework for fields of practice that range from individual and team coaching to organisation development. To be honest, it’s difficult to pin down definitively without becoming simplistic. After all, we work with people, cultures, systems and contexts that are dynamically complex. Different people, situations and times call for different interventions. Here-and-now presence, openness, curiosity and trust are prerequisite conditions for successful outcomes. That said, I often hold 5 x Rs in mind as potential areas for attention. Each R represents a different and inter-related dimension of experience, awareness and practice that commonly influences a client’s inspiration and effectiveness. The Rs are: Results, Relationships, Resourcefulness, Resilience and Reflexivity (sometimes known as ‘critical reflective practice’ or ‘praxis’). I may explore and apply these dimensions with a client at different levels ranging from intra/inter-personal to organisational. Results focuses on who or what is most important to a client and other key stakeholders and taps into e.g. vision, values, purpose, strategy, plans and outcomes. Relationships focuses on the quality of client contact with and between key stakeholders and taps into e.g. ethics, cultures, systems, synergies and dependencies. Resourcefulness focuses on solutions, strengths and opportunities in the client/environment and taps into e.g. spirituality, talent, creativity, innovation and networks. Resilience focuses on client health, wellbeing and sustainability and taps into e.g. motivation, engagement, patterns-trends, agility and flow. Reflexivity focuses on the client’s critical self- and situational awareness, stance and actions and taps into e.g. assumptions, constructs, influences, behaviours and decisions. I place the latter at the centre of this model because, at best, it radically questions, challenges and guides all other dimensions. It lays at the heart of transformational change. What frameworks do you use and find most useful? Conventional wisdom tells us this: if we acquire more resources, we can do more and achieve more. Correspondingly, if we have less, we can do less and achieve less. It’s as if there’s a direct 1-2-1 causal relationship between resource and ability. The language we use in organisations often reinforces this view. We grow and shrink our ‘human resources’ according to the number and size of jobs that need to be done, tasks that need to be performed. It’s a linear logic. And it’s wrong.

Let’s flip this around a bit. A charity plans to run a leadership development programme but loses the funding to do it. It lost the resource so lost the programme, right? No, it explored alternative ideas and found a commercial organisation that was willing to run a high quality programme for it pro bono. It satisfied the charity’s need for a programme and the commercial organisation’s desire to support ethical work in the community. A great outcome for both parties. A win-win solution. So what made the difference? Was it a shift in resources - or a shift in thinking? Here’s the thing: ‘How else might we do this?’ invites lateral thinking, creative ideas and innovative approaches. It takes us away from acquiring more resources and towards becoming more resource-ful. It moved this charity away from, ‘How can we get more money to support our work?’ towards, ‘Who shares similar passions and interests?’ and, ‘What might be possible to achieve our mutual goals?’ This is, of course, the domain of agile thinking. As environments become increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA), we need to think ever more creatively, adaptively and resourcefully. This implies a fundamental paradigm shift away from human resources and towards resource-ful humans. It means shifting our attention beyond solving the immediate issue to developing critical thinking, creative ideation and reflective practice. How do you do it? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed