|

‘The people living in darkness have seen a great Light; on those living in the land of the shadow of death, a Light has dawned.’ (Matthew 4:16, the Bible) ‘Death is a thick black wall, against which every soul is hurled and shattered.’ I don’t now remember who said that, but I do remember my philosophy lecturer quoting it when we studied existentialism. These are very dark words indeed and have, for me, a deeply foreboding and chilling feel to them. I sat down and avidly wrote an essay in response, doing my best to present what, I believed, were convincing rational arguments to counter such a nihilistic and hope-less outlook. When I got my paper back, the mark was nowhere near as high as I had hoped for or expected. The lecturer had commented simply yet profoundly that an existentialist writer would have absolutely no interest in my reasoning. It’s not about objectivity or logic. It’s about how it is and feels to be in the world; a phenomenological cry of angst in the face of fragile, fathomless, futility. It was as if, in my attempt to offer ‘correct’ thinking, I had totally missed the point. It never was about thinking. As the years have passed by, I too have known that angst, at a times an almost irresistible magnetic-like pull towards my own death. Sometimes, it has felt like half-clinging on weakly to avoid being pulled over the edge. In the face of unbearable and irreparable heartbreak, suicide can feel like a least-painful solution. Tom Walker’s moving song, Leave a Light On has deep emotional resonance here. Jesus is my life-saving Light. ‘At the end of the day, it’s either God or death.’ (James Wallace). Whatever Advent means to you, Light shines in darkness. Hold onto hope.

22 Comments

'Now kings will rule and the poor will toil, and tear their hands as they tear the soil. But a day will come in this dawning age, when an honest man sees an honest wage.' (U2) The topic of ethics can sound and feel abstract, esoteric. Something confined to philosophy lectures. The mysterious realm of armchair academics. What does it look like in practice? Why has it become such a critical issue for organisations and societies now? Jasmin, a Filipina, is from the poorest of the poor. To her amazement, and as an answer to prayer, she finds herself with an opportunity to build a small kitchen. She looks for contractors to do the work. The first question she checks is whether the labourers are paid a fair wage. In a country and industry marred by corruption, exploitation is rife. The second is whether they will build with love, if they will pour their hearts as well as their construction skills into achieving a good result. This is so different to a purely commercial transaction. It’s about spirit, attitude – and trust. Against this backdrop, I find it helpful to think about ethics, at its simplest, as values with a moral dimension. For Jasmin, it’s about lifestyle, relationship and stance. Stance infers a choice. We are faced with a decision-point, a junction in a metaphorical road. Pragmatic wisdom would suggest a weighing up of costs against benefits. Ethics would ask who is affected and how? What would be ‘good’ and ‘right’? Why this, and why now? I look up and look around: corruption; media manipulation; climate change; environmental disaster; poverty; human rights abuse; war. How did we get here? I see the poor and vulnerable affected the most and the worst. Yet still, closer to home and within me: a temptation to put my own interests first; to close my eyes; to dull my heart; to deceive my mind; to choose the easier and expedient path. So, what does ethics look like? I ask Jasmin and her life speaks: ‘Pray, love and take a stance.’ ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ (The Clash)

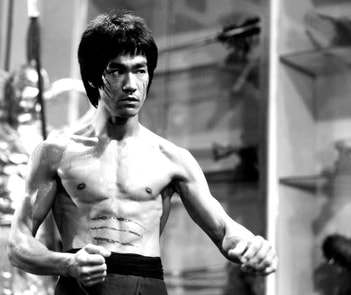

Buridan’s Ass: a paradox in which a hungry donkey finds itself standing precisely midway between two identical stacks of hay. Vacillating with indecision because there are no grounds for choosing a preferred option, the poor donkey starves to death. Whilst often used in philosophy to debate issues of free will vs determinism, this allegory also serves as a graphic illustration of ambivalence. ‘Ambivalence is simultaneously wanting and not wanting something, or wanting both of two incompatible things…Take a step in one direction and the other starts looking better. The closer you get to one alternative, the more its disadvantages become apparent while nostalgia for the other beckons.’ (Miller, W. & Rollnick, S., Motivational Interviewing: Helping People to Change, 2013). We may experience this tug-of-war viscerally when faced with important and equally-compelling choices between X and Y in, say, relationships, careers or other significant life decisions. We may, likewise, experience a paralysis of analysis, a type of over-thinking if multiple options are available to us yet with no unequivocally-convincing reason to choose one course of action over another. Ambivalence can leave a person procrastinating, ineffective, drained and frustrated. It’s as if relative pros and cons balance out and leave us stuck. So how to break the deadlock and enable a change? Here are some ideas. 1. Enable a person to step back from the immediate decision to see a bigger picture. ‘What’s more important here: to make a choice, or to choose one option over another?’ 2. Ask the person: ‘What’s your intuition or gut instinct telling you, irrespective of whether or not you can see a rationale for it?’ 3. Help the person to explore different and broader perspectives: ‘Which option would e.g. God, your CEO, your team, your family or yourself 5 years from now, prefer you to take?’ 4. Support and challenge the person to take a decision and to stick with it. How do you deal with ambivalence? Do you feel stuck? Get in touch! ‘The only exercise some people get is jumping to conclusions.’ (Hal Elrod) A recurring theme in psychological coaching/OD is that of enabling a person or a team to grow in awareness of what they are believing, assuming, hypothesising or concluding. This could be about, for instance, themselves, another person, a relationship or a situation. In Yannick Jacob’s words, ‘Human beings are meaning-making machines’ (An Introduction to Existential Coaching, 2019). We are wired to see things as complete wholes and, where there are gaps, to fill them subconsciously – and therefore, by definition, without noticing we are doing it. This reflects a core concept in Gestalt psychology; where you may be familiar with, say, an image of black shapes on a white background that viewers typically see as a ‘panda’. This assumes, of course, that the person seeing the image already has an idea of panda in mind – i.e. what a panda looks like. We join the dots or, in this case the shapes, to create something that we already know. In doing so, we superimpose meaning onto the image and, at the same time, exclude alternative interpretations. It’s as if, to us, if the image is self-evidently that of a panda. Full stop. This panda-perceiving phenomenon can help us to understand how we, as individuals and as cultural groups, construe our ideas of reality at work. Drawing on limited data, we fill-in any gaps (e.g. with our own hopes, anxieties or expectations) to create what looks and feels, to us, like a complete understanding of a situation. Yet, in Geoff Pelham’s words, ‘The facts never speak for themselves’ (The Coaching Relationship in Practice, 2015). If we enable a person or a team to revisit the gaps and to hold their hypotheses lightly, fresh insights and opportunities can arise. First, pay attention to how a person is feeling, or the mood in a team. Acknowledge the emotion without necessarily seeking to change or to resolve it. Instead, invite a spirit of curiosity, a desire for discovery. Next, facilitate a process of critically-reflexive exploration: e.g. of what meaning they are making of their experience; of what needs it reveals; of what strategies they are using to address them. Now, offer support and challenge to test assumptions, stretch boundaries, shift a stance. Be prayerful and playful. Release the panda to emerge as something new. I have been gripped by The Legend of Bruce Lee (2008), a Chinese biographical drama on Netflix. As we see the extraordinary life of this iconic figure in history depicted on screen, I’ve been stimulated to reflect back on my own life too. In my teenage years, dabbling with martial arts, Bruce Lee stood out as the pinnacle, the expert that everyone admired and aspired to be like. His unique sparring technique bordered on the impossible; his philosophy was mysterious, yet strangely compelling. But, how did he get there? What can we learn as leaders, coaches and trainers from this amazing life? The first thing that strikes me (if you will excuse the pun) is that Bruce’s gift to the world arose, initially, in response to being bullied by racist thugs. He was absolutely determined to stand up to them, and therein began his martial arts quest in earnest. Having defeated his nemesis, however, Bruce found grace when his hitherto arch-enemy apologised and sought reconciliation. How far do we, and those we work with, seek, discover and create gifts in the midst of adversity, rather than simply bemoan it? How far are we, and they, open to the transforming power of forgiveness? The second is Bruce’s total single-mindedness in pursuit of his vision, passion and goal. He had a clear sense of purpose and justice in life, sometimes describing it in spiritual terms as a Divine force, and was unswervingly-unwilling to deviate from it. It meant that all other considerations had to be pushed to one side. He was willing and committed to do whatever it takes, and to persist in that until the end, never being satisfied with mediocrity. How far do we, and those we work with, tap into spiritual-existential vision and values and hold to them? Do we, and they, settle for compromise too easily? The third is Bruce’s passion for philosophy-in-action. His new martial arts discipline wasn’t just about fighting style. It was deeply embedded in and influenced by his philosophical and psychological study, observation, reflection and experimentation. In this way, his philosophy was practical and his practice was philosophical. Each was grounded dialectically and ethically in the other. Bruce would continually invite challenge from peers and experts to test, stretch and refine. How far do we, and those we work with, engage proactively with studies, peer networks and critical reflective practice? The fourth is Bruce’s open-handedness. Whereas most schools of martial arts at the time were purist and exclusive, Bruce sought actively to learn from others engaged in different forms and to share his learning too. This frequently brought ferocious and oft-violent conflict from people who felt envy or threatened by his values and approach, people who had a powerful vested interest in the status quo, yet this didn’t dissuade him from his path. He was more interested in a higher goal than self-interest; motivated more to learn, develop and enhance than to win per se. How far is that our spirit too? The fifth is Bruce’s backdrop circle of family, friends and colleagues that supported his exceptional achievements. They stood by Bruce through thick and thin, learning from him, sharing his vision and using their gifts, talents and resources to enable him to realise his dazzling mission. As I watched this astonishing life-drama unfold on TV, I couldn’t help thinking of parallels with Jesus Christ and his disciples, of ancient philosophers and their students. It inspired and refreshed my ideas of leadership and teamwork. Who supports you and those you work with, enabling your, and their, success? ‘Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.’ – Albert Einstein

I saw a blog by Tony Clark on Heart of the Art this morning and found it so inspiring that I thought I'd share an extract here: Take a minute to scan your surroundings. Are you in a familiar place or somewhere new? Stop reading this, and just look around you. Pick out an object, maybe something you hadn’t noticed before, and focus your attention on it. If you really focus, it’ll get brighter and more “real” than it was when it was just an unnoticed piece of the background noise of your life. Now, try to view your surroundings from the point of the object. Some people can do this with no effort, and for others, it takes some concentration. Depending on how adept you are at focusing your concentration, you may notice a slight shift in your perception – a weird jump in realty, where you are suddenly viewing the world from a different perspective. What do you think..? How would you describe your coaching style? What questions would you bring to a client situation?

In my experience, it depends on a whole range of factors including the client, the relationship, the situation and what beliefs and expertise I, as coach, may hold. It also depends on what frame of reference or approach I and the client believe could be most beneficial. Some coaches are committed to a specific theory, philosophy or approach. Others are more fluid or eclectic. Take, for instance, a leader in a Christian organisation struggling with issues in her team. The coach could help the leader explore and address the situation drawing on any number of perspectives or methods. Although not mutually exclusive, each has its own focus and emphasis. The content and boundaries will reflect what the client and coach believe may be significant: Appreciative/solutions-focused: e.g. ‘What would an ideal team look and feel like for you?’, ‘When has this team been at its best?’, ‘What made the greatest positive difference at the time?’, ‘What opportunity does this situation represent?’, ‘On a scale of 1-10, how well is this team meeting your and other team members’ expectations?’, ‘What would it take to move it up a notch?’ Psychodynamic/cognitive-behavioural: e.g. ‘What picture comes to mind when you imagine the team?’, ‘What might a detached observer notice about the team?’, ‘How does this struggle feel for you?’, ‘When have you felt like that in the past?’, ‘What do you do when you feel that way?’, ‘What could your own behaviour be evoking in the team?’, ‘What could you do differently?’ Gestalt/systemic: e.g. ‘What is holding your attention in this situation?’ ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What are you inferring from people’s behaviour in the team?’, ‘What underlying needs are team members trying to fulfil by behaving this way?’, ‘What is this team situation telling you about wider issues in the organization?’, ‘What resources could you draw on to support you?’ Spiritual/existential: e.g. ‘How is this situation affecting your sense of calling as a leader?’, ‘What has God taught you in the past that could help you deal with this situation?’, ‘What resonances do you see between your leadership struggle and that experienced by people in the Bible?’, ‘What ways of dealing with this would feel most congruent with your beliefs and values?’ An important principle I’ve learned is to explore options and to contract with the client. ‘These are some of the ways in which we could approach this issue. What might work best for you?’ This enables the client to retain appropriate choice and control whilst, at the same time, introduces possibilities, opportunities and potential new experiences that could prove transformational. What is real, what is true, how can we know? These are questions that have vexed philosophers for centuries. In more recent times, we have seen an increasing convergence between philosophy and psychology in fields such as social constructionism and existential therapy. How we experience and make sense of being, meaning and purpose is inextricably linked to how we behave, what we choose and what stance we take in the world. As a Christian and psychological coach, I’m intrigued by how these fundamental issues, perspectives and actions intertwine with my beliefs, spirituality and practice. Descartes once wrote, ‘If you would be a real seeker after truth, you must at least once in your life doubt, as far as possible, all things.’ It’s as if we must be prepared to suspend all assumptions about ‘what is’, to explore all possibilities and dare to think the unthinkable in order to grow and make our best contribution. Things are not always as they at first appear. There are sometimes multiple explanations for the same phenomenon, depending on the frame of reference we or others use to interpret it (see, for instance, Gareth Morgan’s seminal work, Images of Organisation, 1986). We are sometimes blinded to what’s in front of us by our prejudices, preconceptions, cultural constraints or rigid views of the world. It can be hard to maintain healthy scepticism without cynicism. I see it with clients, sometimes in myself too. A sense of being trapped by a fixed Gestalt, a cognitive distortion, an inherited or learned belief system. An inability to see, to recognise the box that we’re in, never mind to see or think outside of it. An avoidance of deep, difficult questions because of the discomfort, confusion or anxiety they may evoke. If we’re not careful, if we can’t find the right help when we need it, it may limit our lives and our learning. I think this is where coaching can play a very important role, helping pose and address some deep questions. Nick Bolton commented insightfully in Coaching Today that, ‘To explore a coaching issue existentially is to understand the relationship that the presenting problem has to the human condition to which it is a response, and to remain focused on enabling a change of perspective that allows the client to move past their current challenge.’ He also provided some helpful examples: ‘For instance, how is a client’s procrastination around something that seems to matter to her a failure to remember that life comes to an end? How is a client’s need to be unconditionally loved by his partner an attempt to deal with existential rather than interpersonal isolation? (And the solutions are very different things). How is someone’s lethargy simply a part of their fear of taking responsibility for their life?’ (July 2013, p17) A metaphysical, existential or theological dimension can shift the entire paradigm of the coaching conversation. The question of whether a client should apply for this or that job is influenced by her sense of purpose. If she is willing to consider that God may exist and have a plan for her life, the whole situational context will change. It can be a dizzying and exciting experience, yet it’s really a question of how courageous and radical we and the client are prepared to be. I had precautionary tests this week for a potentially life-threatening condition. Thankfully, the results turned out to be OK but it’s experiences like this that often bring existential issues into sharp relief. Existential coaching focuses on helping a person explore his or her own sense of ‘being in the world’, that strange psychic awareness that we are in the world before what we are in the world. At times, such awareness can feel mysterious, unfathomable, disorientating and anxiety-provoking. It’s like one of those moments when, as a child, I gazed up into the night sky, saw the stars and the enormity of space, imagined space and time going on forever and felt dizzy and perplexed by it. It can also raise deep questions to the surface such as, ‘Who am I?’ and 'Why am I here?’

According to existentialist thought, our essence as a person isn’t fixed but we become who we are through the choices we make. Our choices are influenced by factors such as the assumptions, beliefs, judgements, hopes and fears etc. we hold about ourselves, the same we hold about others and how we experience and act in our relationships with others, in our everyday circumstances and in the decisions we face and make. Existentialist writers sometimes refer to this as our ‘stance in the world’, that is, how we perceive, position ourselves and act in our everyday lives. Our stance both reflects something of our sense of and our way of being in the world and shapes who we are and become in the world. I can share a personal example to illustrate this phenomenon. When my youngest daughter was 7 years old, I took her to a theme park that had a very high and steep ‘death slide’. I was surprised and impressed to see her quietly but resolutely psyche herself up to leap down its harrowing slope. When she finally did do it, I asked her how she managed to bring herself to push herself off its terrifying edge. She responded in a way that humbled and amazed me: ‘Firstly, when you told me it would be OK, I trusted you that it would be OK, even though it looked so scary. Secondly, when I write about what we did today in my diary tonight, I want to be able to write that I went on the slide even though I was afraid of it, not that I didn’t go on the slide because I was afraid of it. That’s the kind of person I want to be.’ I felt awe-struck and speechless. Curiously, we are often unaware of making choices, or deny to ourselves that we are making choices in order to avoid the responsibility that choice implies, and unaware of the underlying metaphysical world view we hold that both influences and is influenced by our choices. It’s as if we can live at a superficial level, sometimes choose to live at that level as a form of self defence or life-coping mechanism. The problem is that if we only live at that level, we may fail to be who we can become in the world; deny ourselves and others a deeper and more fulfilling life experience; struggle with contact in intimate relationships; expend our time, energy and resources on distractions that aim to suppress or avoid facing the discomfort and anxiety that existential issues can evoke. One of the goals of existential coaching is therefore to raise world view and choice into awareness in order enable clients to live more authentic lives. It’s about enabling clients to acknowledge and deal with underlying anxiety, tensions and conflicts that could be experienced symptomatically in psychological, emotional, physical or relational difficulties or in problematic patterns of behaviour. Duerzen summarises this approach in Skills in Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy (2011) as, ‘to help people to get better at facing up to difficulties with courage instead of running away from them’. It necessarily involves a willingness to explore issues beneath the surface, a willingness to face anxiety and a willingness to explore alternative ways of being and acting in the world. This reminds me of a volunteer assignment I did with a Christian social worker and psychologist in Germany not long after the Berlin wall came down and East and West were reunified. We were working in a social work project with young people, often from fairly poor and dysfunctional family backgrounds, who were being seduced by the far right to join new neo-Nazi groups. The groups provided these young people with a much-needed sense of identity, belonging and purpose in the world. As part of his practice, the social worker would touch sensitively on spiritual issues and questions where it seemed appropriate. A secular humanistic colleague challenged him vehemently on this, insisting that social workers should never stray into the spirituality arena. The social worker empathised with his colleague’s concerns about professional ethics and the risks of pressurising and indoctrinating vulnerable young people. At the same time, he believed that true spirituality speaks to life’s deepest questions, experiences and actions. The social worker responded, ‘These young people often talk in therapy about their deepest fears, about life and death, issues that are very real for them. It’s often such fears that lead them to seek a sense of identity, security and purpose in these sinister groups. We cannot afford to separate our thinking or our practice into neat, distinct, spheres of influence. The matters we and they are dealing with bring profound psychosocial, existential and spiritual issues face to face in the room.’ I agree. So what could existential coaching look like in practice? Firstly, the coach will invite the client to share their story, particularly focusing on issues that led them to work with a coach in the first place. The coach’s role at this stage is primarily to listen and, over time, to reflect back any beliefs and values that surface implicitly or explicitly in the client’s account, particularly in terms of how the client perceives themselves, others, issues and their situation. In this sense, the coach is acting as a sounding board and a mirror, enabling the client to grow in awareness of his or own world view. The coach will go on to focus on specific tensions that may emerge, e.g. between the client’s underlying beliefs and values and the stances or actions they are choosing in practice. The intention here is to surface the client’s underlying personal and cultural metaphysic rather than simply his or her way of perceiving and responding to an immediate issue. This approach is based on a belief that the client’s general world view or stance-in-the-world will influence e.g. what issues the client perceives as significant; how they perceive, experience and evaluate them; what their subjective needs and aspirations are; what approaches and actions they will consider valid or appropriate; what actions they will be prepared to commit to and sustain etc. This approach also enables the client to explore any tensions within their world view, between that world view and those of others in their situation and between their world view and their actions. The problem with the language of ‘world view’ in describing such an approach is that that it sounds too conscious, too cognitive, too coherent. The focus of existential coaching is profoundly subjective and phenomenological, that is, how the client actually experiences and responds to his or her being-in-the-world at the deepest psychological levels. In that sense, it’s as much about how a person feels, the questions they struggle with and what they sense intuitively as what they may think or believe rationally. Again, there are important links for me with a spiritual dimension. As I faced my own health-related tests this week, for instance, I experienced my faith in God as something more like a subconscious, mysterious, inner ‘knowing’ than a rational assent to a set of beliefs. As the coaching conversation progresses, the coach may help the client identify choices he or she is making (including by default), potential choices he or she could take in the future and how to integrate the client’s choices with his or her chosen being and stance in the world in order to live a more authentic and thereby less conflicted life. At one level, this enables the client to become more aware of and honest about their decisions and actions and to act with a greater sense of freedom and responsibility. At another level, it opens up more opportunities for the future than the client may have perceived previously. It can feel very liberating and energising to discover fresh ways of perceiving and acting in situations that have previously felt stuck or entrapping. Sample coaching methods could involve helping the client reframe experiences as choices or to change their language from passive to active voice. For example, ‘I have to write this report for my boss by Friday’ or ‘This report needs to be written by Friday’ sound and feel less empowering than, ‘I will choose to write this report for my boss by Friday’. It enables the client to take ownership of their choices and to weigh up alternative courses of action. After all, if it’s a choice, I can choose differently, although I will need to weigh up the relative pros and cons of different choices. My best choices are congruent with my underlying beliefs and values, e.g. in this case, respect for authority, the sense of a job well done or a desire to keep my job so I can pay my bills. The coach is likely to help the client connect their choices with their underlying world view. One way to approach this is to use the ‘7 whys’ technique whereby each time the client explains why they are choosing a certain course of action, the coach responds with, ‘…and why is that important to you?’ until the client’s deepest values, aspirations and anxieties surface. I will end this piece by posing some brief existential questions for personal reflection: Who am I? What personal stance do I want to take in the world? How do I handle contradiction, ambiguity, uncertainty and paradox? What is most important to me? What is God or this situation calling for from me? How consistent are my choices with my values? How well do my actions reflect the person I aspire to be? Critical reflexivity…hmm…what’s that? Sounds complicated. It's something about noticing and paying attention to our own role in a story; how I influence what I perceive in any relationship, issue or situation. I was re-reading one of my favourite books, An Invitation to Social Construction (2009) by Kenneth Gergen this morning which introduces this concept with the following explanation: ‘Critical reflectivity is the attempt to place one’s premises into question, to suspend the ‘obvious’, to listen to alternative framings of reality and to grapple with the comparative outcomes of multiple standpoints…this means an unrelenting concern with the blinding potential of the ‘taken for granted’…we must be prepared to doubt everything we have accepted as real, true, right, necessary or essential’. I find this interesting, stimulating and exciting. It’s about journeying into not-knowing, entertaining the possibility that there could be very different ways of perceiving, framing or experiencing issues or phenomena. It’s about a radical openness to fresh possibilities, new horizons, hitherto unimaginable ideas. It’s a recognition that all my assumptions and preconceptions about reality could be limiting or flawed. I’ve found this critical reflexivity principle invaluable in my coaching and OD practice. How often people and organisations get stuck, trapped, by their own fixed ways of seeing and approaching things. The same cultural influences that provide stability can blind us to alternative possibilities. The gift of the coach or consultant is to loosen the ground, release energy and insight, create fresh options for being and action. It resonates with my reading of the gospels. Jesus Christ had a way of confronting the worldviews, traditions and apparent ‘common sense’ outlook of those he encountered in such a way that often evoked confusion, anger or frustration. It’s as if he could perceive things others couldn’t see. He had a way of reframing things that it left people feeling disorientated. He operated in a very different paradigm. I will close with words from Fook & Askeland (2006): ‘Reflexivity can simply be defined as an ability to recognise our own influence – and the influence of our social and cultural contexts on research, the type of knowledge we create and the way we create it. In this sense, then, it is about factoring ourselves into the situations we practice in.' |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed