|

‘Grief is not a disorder, a disease or a sign of weakness. It is an emotional, physical and spiritual necessity, the price you pay for love. The only cure for grief is to grieve.’ (Earl Grollman) Ambushed by grief. A graphic book title and a profound way to convey the experience of the experience. Grief can, at times, take us completely by surprise, impacting us suddenly and as if out of nowhere; leaving us breathless, broken and bleeding. My most traumatic grief experience was at age 18. I still re-experience it, like living in the vice-like grip of a terrible nightmare that stubbornly, agonisingly and tormentingly won’t let go. One of the best descriptions of grief I’ve ever read is a beautiful and painful personal expression of this phenomenon that, in the midst of such agonies, offers a picture of hope. It resonates with much of my own personal experience too. Only in more recent years have we begun to discover, perhaps to rediscover and to understand, the somatic dimensions and consequences of traumatic grief. The body certainly does keep the score. On Easter Saturday (a day that marks the existential time gap between Jesus’ death and his resurrection) this year, I visited a Christian community where one of its leaders shared a deeply evocative short video clip by Massive Attack. It captured and expressed feelings of denial, betrayal, pain, abandonment and death in such a way that left me stunned and speechless. We prayed for all who feel trapped in a perpetual state of dysthymia.

12 Comments

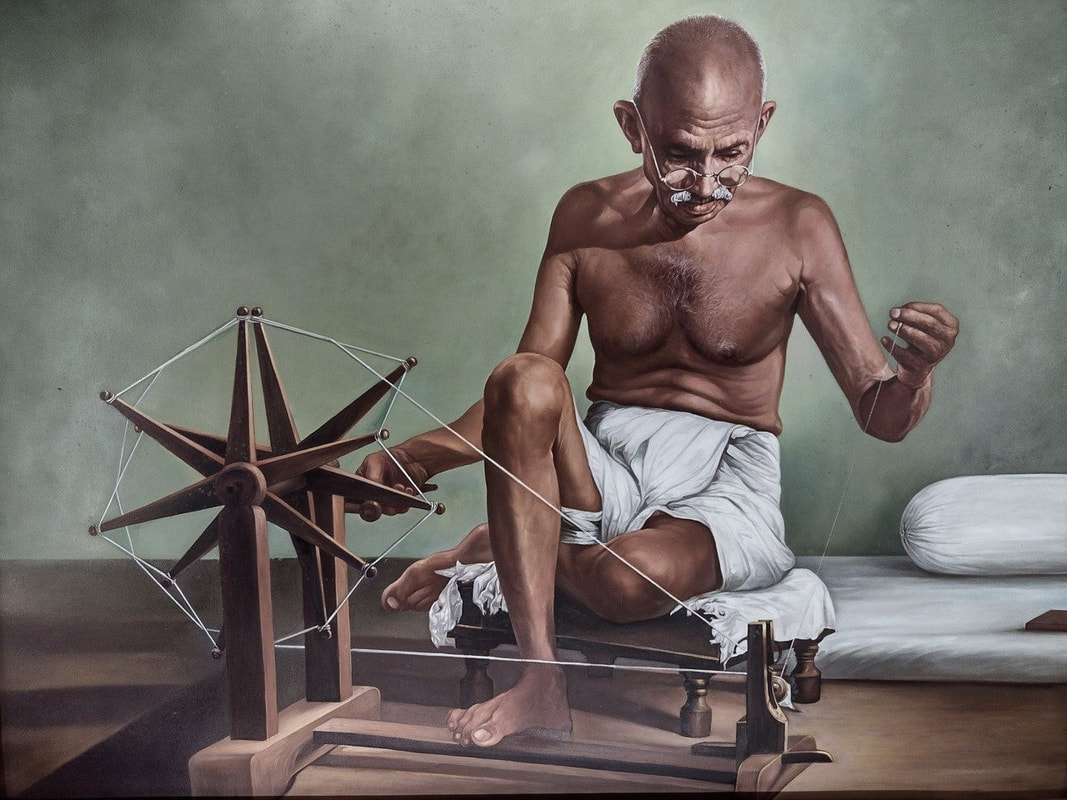

‘We're fascinated by the words – but where we meet is in the silence behind them.’ (Ram Dass) I remember my first experience of haggling over the price of a leather belt in a Palestinian marketplace. I was a teenager at the time and I found this approach to buying and selling novel and entertaining. The smiling street vendor played the game skilfully. I asked, ‘How much?’ to which he responded, '$6.’ ’$6?’ I replied, ‘I could get the same belt at another stall for $1. How about $2?’ ‘$2?’ He replied, ‘Please don’t insult me. It cost me more than that to make it. As a special deal, however, I’ll give it to you for $5.’ ‘$5?’ I replied, ‘The most I would pay for it is $4.’ ‘$4?’ He replied. ‘Don’t you realise I have a family and children to feed?!’ He grinned. We closed at $3. To a Westerner, where buying and selling is typically more transactional than relational, this toing and froing can feel like a manipulative game; frustrating, bordering on dishonest and time-wasting. That’s mostly because we tend to miss the underlying cultural meaning and purpose to this type of engagement. I met recently with an international team from USA, Netherlands, Jordan and South Africa. They are part of a Christian organisation and were keen to identify and work through some cross-cultural and relational challenges. I decided to share a short passage from the Bible with them, then to invite them to discuss what sense they made of it: “Jesus withdrew to the region of Tyre and Sidon. A Canaanite woman from that vicinity came to him, crying out, ‘Lord, Son of David, have mercy on me! My daughter is demon-possessed and suffering terribly.’ Jesus did not answer a word. So, his disciples came to him and urged him, ‘Send her away, for she keeps crying out after us.’ He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.’ The woman came and knelt before him. ‘Lord, help me!’ she said. He replied, ‘It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.’ ‘Yes it is, Lord,’ she said. ‘Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.” And now to the critical closing: “Then Jesus said to her, ‘Woman, you have great faith! Your request is granted.’ And her daughter was healed at that moment.” (Matthew 15:21-28) To the Westerner who views language and transactions in literal, linear, straight lines, Jesus’ initial responses to the woman are shocking. We take his opening action as his definitive stance. We don’t see the smile on his face or the glint in his eye, or understand the movement as the interaction progresses. We may assume the story is written to affirm the woman’s perseverance. We may think she has changed his mind. We are likely to miss the Semitic ritual of building or navigating a relationship. The Jordanian participant saw this immediately. The others looked surprised. (I must confess I didn’t understand this, too, until a Kurdish-Iranian friend had explained this dynamic to me). The cross-cultural implications are clear. If I judge your actions by unknowingly mis-inferring your intentions (being influenced subconsciously by my own cultural assumptions), all kinds of misunderstandings and tensions can arise. It cautions me-us to approach people and groups from different cultures with an open mind, a spirit of curiosity and a great deal of humility. Bottom line: We’re not only negotiating a price; we’re also negotiating a relationship. ‘Is he – safe? I shall feel rather nervous about meeting a lion.’ ‘Safe? Who said anything about safe? Of course he isn’t safe. But he is good.’ (C.S. Lewis: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) I was 8 years old when the teacher asked us, a classroom of children, to sit on the floor while she read to us the next chapter of a novel, ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’. If you know the book, it was the part where Aslan the lion (which, I discovered later, the author had used to depict Jesus) appears in Narnia, a mythical world that represents this world. It's a beginning of real hope. This snow-covered land, which hitherto had been trapped under a curse of perpetual winter, is beginning to thaw. Meanwhile, the antagonist, an evil witch (depicting Satan), comes across a small group of woodland creatures enjoying a party to celebrate. She flies into a rage, interrogates them harshly and uses her magic powers to turn them into stone. At that awful and unexpected moment, I remember bursting into tears. As a child, I was horrified that, just as things had started to look up for these innocent animals, their lives and hopes had been shattered. It felt like a moment of despair for them – and for me. (A therapist-supervisor commented recently that little wonder most of my subsequent adult life has been spent in community work, human rights and international development). Today as I, along with Christians across the world, reflect on Jesus’ death on the cross, I’m reminded again of terrible injustice and violence against the innocent. I often identify more with Edmund than with Peter in Lewis' drama, yet what matters most is Aslan. It's He who breaks the power of the witch. ‘Chance is perhaps the pseudonym of God when he doesn’t want to sign.’ (Anatole France) I enjoyed a very tasty Eritrean meal with an inspiring young couple today. I had met this bright young man on a plane on my way to Germany last year and we had chatted throughout the flight. It turned out his equally-talented partner is involved in very similar work to my own, including internationally, so we agreed to keep in touch with each other on our return to the UK. As we met up again for the first time today, we talked about our shared faith in Jesus and his profound significance in our lives. We talked, too, about ways in which we’ve witnessed his mysterious power at work. As I listened to this couple's stories and experienced their generosity and warmth, I had a deep sense this encounter was far more than coincidence. When have you experienced encounters that somehow felt sacred? ‘Always vote for principle, though you may vote alone.’ (John Quincy Adams) I never had the privilege of meeting Soji Taguchi, but I do wish I had. Soji was a manager at a Japanese-owned textiles factory in the Philippines. Seeing how meagrely the Filipino workers were paid, he gave away a significant portion of his own salary each month to top up theirs. When a young Filipina was severely distressed one day and, in her upset, damaged an expensive piece of machinery, he paid for the repairs himself. Instead of chastising her he listened to her plight and, subsequently, regularly slipped money (secretly) into her pockets to help her, a poor teenager, to pay her bills. This woman’s life is now a clear reflection of his. The power of a positive role-model. Ted Winship was my mentor, a shopfloor supervisor at an industrial site in the UK. Once, the workers refused to enter an enclosure because the conditions in it were so terrible. The manager told Ted that, if he could persuade them to do the work, they would all be paid a substantial bonus. Ted took the manager at his word. He entered the compound first and the work was completed on time. At the end of the project, however, the manager refused to pay the bonus and only gave Ted his. It was a serious breach of trust. On hearing of this betrayal, Ted confronted the manager but to no avail. He distributed his own bonus to the workers, resigned from his job and walked out. Ethics in action. Self-sacrifice for the sake of others. The personal costs were high – but the spiritual benefits were immeasurable. ‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life? ‘Coincidence doesn't happen a third time.’ (Osamu Tezuka) I arrived in the Netherlands on Saturday, aiming to orientate myself briefly to this new country before working with an INGO team there on Monday. When I stepped into my hotel room, however, it smelt damp and sweaty. Trying not to breathe, I opened the windows to an icy blast and decided to go for a walk while the fresh air did its work. Not far away, I noticed a church building so walked over to have a glance at its meeting times. As I did so, I looked up and saw a cross in the sky, a misty symbol painted momentarily on blue canvas by vapour trails. It felt significant, but I didn’t know why. The next day, the church was full when I arrived and I sat quietly in the midst, happily surprised by how much Dutch I could understand. (I can speak German, but this was my first time to read this new language). At the end, a woman kindly introduced herself to me. On learning that I am English, she explained that the church is recovering from an intensely painful internal conflict. The pastor had spoken on a need to look to God. I showed her the photo I had taken the day before – a symbol of suffering and hope – and she started to weep. ‘God brought you here to us this morning, Nick.’ Another woman now introduced herself, explained briefly that she had worked internationally in medical mission, and invited me to a special meeting that afternoon for asylum seekers and refugees. ‘How could she possibly have known anything about my life and work?’ I asked myself, a total stranger. The guest speaker that day was a visitor from Algeria and, serendipitously, works for the same organisation I was about to work with the following day... as does a man who randomly found himself sitting beside me in a hall full of people. Was this all coincidence? I don’t believe so. You decide. ‘We don’t have a plane crash scheduled for today, but I thought I’d take you through the emergency procedures just in case.’ (KLM Air Hostess) I love the difference that a sense of humour can make. The air hostess (above) made everyone laugh during the passenger safety briefing on a return flight from the Netherlands today. The airline’s own plane had experienced maintenance problems so it had had to borrow one from another airline. One hostess complained, with a glint in her eye, that the green décor didn't match the blue colour of her uniform. The passengers all laughed when another hostess made an announcement too, aiming to draw our attention to an apparent information light on the plane…only to correct herself moments later with, ‘Oh – this plane doesn’t have one!’ Brilliant. It took the terror out of the turbulence. On a more serious note, I had been in the Netherlands to work with a diverse NGO leadership team, to support its desire to enhance its international teamwork. I referenced briefly a couple of places in the Bible where the writer comments on the amazing potential of human diversity – where the Divine whole is seen, known and experienced to be more than the sum of its parts – yet also hints at the corresponding dark risks of undervaluing, fragmentation and conflict if not. Strikingly, the writer moves on in both places to emphasise a deep need for authentic love as the critical success factor. This insight set a spiritual-existential tone for the day, as we reflected on team-as-relationships. Returning to the plane – but this time as a metaphor, a participant from South Africa asked, ‘How many separate parts is a Boeing 747 aircraft made up of?’ Apparently, the answer is about 6,000,000. ‘And what do these diverse components all have in common?’ Puzzled faces all round now. ‘None of them can fly.’ I thought this was genius. What a great way to dispel the myth of the all-sufficient self in the face of the dynamic complexities of teams, organisations and wider world. We worked through an Appreciative Inquiry next, drawing on positives of the past and aspirations of the present to co-create shared trust and vision for the future. Set the trajectory. Fasten seatbelts. Enjoy the flight. ‘You could start a fight in an empty room, mate.’ (Allan Jones) I’ve never sought conflict. Far from it. I much prefer harmony and peace. That said, however, I can’t escape a similar calling to that which Martin Luther King once heard: ‘Stand up for righteousness! Stand up for justice! Stand up for truth!’ It’s a call that burns deeply inside of me and has done, as far as I can remember it, for my entire life. I’m pained to admit that I haven’t always followed that voice anywhere near as courageously as MLK. I haven’t always handled it with his astonishing humility and love. I’ve stayed silent when I should have spoken up or spoken up when I should have stayed silent. My words have stumbled out clumsily. I’ve caused pain where I meant to bring healing and hope. Yet, at times, this vocational stance has proved authentic, valuable and worthwhile. In my 30s, I worked for a large UK charity in the health and social care sector. As an idealistic young radical, I challenged the leadership team on numerous occasions when I believed we were compromising our values. I tried to do this with prayer and humility and out of a genuine desire to build relationship and trust. On one occasion, the leadership team decided, in view of limited budget, to increase only senior leadership salaries until it had secured sufficient funding to increase frontline staff salaries too. I argued vociferously that we should do the exact opposite – and to freeze my own salary as a first step. On another occasion, the leadership team decided to reserve all spaces in its small head office car park for executives only, given that they didn’t have time to drive around to look for parking places elsewhere. I advocated passionately that, especially in the winter months, the spaces should be reserved for female and other vulnerable staff or visitors so that they wouldn’t have to walk along dark city streets at night to their cars. On yet another occasion, the leadership team recruited a ‘hatchet man’ on temporary contract to implement a tough restructure with associated redundancies. I protested that this blunt way of approaching the change would damage relationships, engagement and trust. At times, I imagined my challenges and counter-proposals were met with deafening silence or heavy sighs – especially as I wasn’t a senior leader at the time. Nevertheless, when a serious crisis broke out between the leadership team and entire middle management, both sides to the conflict invited me to mediate as ‘the only person they could trust’. The chief executive, a man of remarkable humility, took me into his confidence and treated me like a respected thought-partner. When I moved on, the company secretary wrote to me to say he had never encountered such integrity. Even the dreaded ‘hatchet man’ wrote that he wouldn’t hesitate to employ me alongside him in any future role. Pray with humility – take a stance – speak the truth in love. ‘Try to be a rainbow in someone’s cloud.’ (Maya Angelou) I can’t create a rainbow. I can only witness its radiant beauty. A rainbow itself is created by white light, refracted as it strikes droplets of water in the air, often seen most vividly during or after rainfall. Some of the most stunning I’ve seen have been in Scotland where sunshine and rain are common together, with bright-coloured rainbows emerging like curvaceous, prismatic streamers in their midst. The Bible depicts rainbows as signs of spiritual-existential promise, of hope, initiated by God. Again, this isn't something I can make happen. I can only witness it, experience it, be awestruck by it. It’s something, or rather Someone, who clings to me amidst the violent storms, raging winds and torrential downpours of my life. Often, quite literally, this has been the only reason why I'm still alive today. Sometimes, I only perceive or discern the traces of a rainbow after the event. It’s like a mysterious pattern that appears, by faith, and is only visible from a distance. I went to theological school for 3 years. Inexplicably, my fees and living expenses were fully-paid. I remember, however, sitting on the side of my bed, alone and in near-despair. Studying God like studying physics felt like a travesty. Years later, the hidden seeds sown through that experience gradually came to fruition. I can now see the deep wisdom in that youthful decision, that strange prompt of divine opportunity that had felt so hard for me at the time. It was a period that had included a broken engagement, a snapped shin bone, tests for throat cancer and many other painful trials. Yet still, somehow...a rainbow appeared. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed