|

‘To understand is to perceive patterns.’ (Isaiah Berlin) According to Gestalt psychology, human beings are hard-wired to see things in patterns. Take, for instance, a tree. If I were to invite you to imagine a tree, it’s likely you would imagine the whole tree (well, at least that part of the tree that is visible above ground). I wouldn’t imagine that you’d picture all its constituent elements separately – cells, leaves, twigs, branches etc. Unless you’re dissecting a tree in a botanical lab. It’s essentially the same idea in music. When we listen to a melody, we hear the tune as a whole, not each individual note separately from the others. In fact, if we were to examine each note in turn in isolation, it’s unlikely we’d be able to discern what melody they form part of when clustered together in a specific configuration. Except, perhaps, if we’re learning to play an instrument and focusing intently on one note at a time. Now this intuitive ability can be a real gift when working with teams, groups, organisations – or even making sense of geopolitics. It means learning to step back from the immediate issue or event and, metaphorically, to narrow our eyes into a near-squint to allow a bigger picture, a wider system, a deeper meaning, the wood for the trees, to emerge. Khalil Gibran observed, ‘the mountain is clearer to the climber from the plain.’ I recognised this phenomenon at work this last week when, in the Netherlands for the first time, the more I relaxed and allowed the language to flow over me, the more of it I could understand. When I paid too much attention to individual words, the more I got stuck. There are parallels in Timothy Gallwey’s Inner Game. Beware paralysis of analysis. Take a breath, relax your grip and notice what surfaces into awareness.

10 Comments

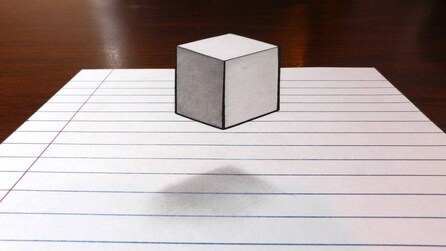

‘It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.’ (Henry David Thoreau) Psychologist Albert Ellis, widely regarded as the founding father of what has today evolved into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, noticed that different people responded differently to what were, on the face of it, very similar situations. Previously, you might have heard, ‘Person X feels Y because Z happened’. It assumed a direct causal relationship between emotions and events. Ellis’ observations challenged this, proposing that something significant was missing in the equation. After all, if this assumption were true, we could expect that everyone should feel the same way in circumstance Z. Curious about this, Ellis concluded that the critical differentiating and influencing factor that lays between emotions and events is belief. It’s what we believe about the significance of an event that affects most how we feel in response to it. Here we have person A who hears news of a forthcoming redundancy with fear and trepidation. He believes it will have catastrophic financial consequences for himself and his family. Person B receives the news with positive excitement. She believes it will provide her with the opportunity she needs to pursue a new direction in her career. Drawing on this insight, organisational researchers Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal proposed that, in the workplace, what is most important may not be so much what happens per se, as what it means. The same change, for instance, could mean very different things to different people and groups, depending on the subconscious interpretive filters through which each perceives it. Such filters are created by a wide range of psychological, relational and cultural factors including: beliefs, values, experiences, hopes, fears and expectations. This begs an important question: how can we know? Hidden beliefs are often revealed implicitly in the language, metaphors and narratives that people use. To observe the latter in practice, notice who or what a person or group focuses their attention on and, conversely, who or what appears invisible to them. Listen carefully to how they construe a situation, themselves and others in relation to it. Inquire in a spirit of open exploration, ‘If we were to do X, what would it mean for you?’; ‘If we were to do X, what would you need?’ This is about listening, engagement and invitation. Attention to the human dimension can make all the difference. At a time when geopolitical tensions between NATO-EU and Russia are on the increase and depicted starkly as such in the media, I showed a video of a Russian 'hell march' to an international group and asked them: a. What do you notice; b. How do you feel; c. What does it mean? It opened a deep conversation that emphasised the need for critical reflexivity in interpreting experiences and events. A Chinese participant looked quite disdainful and said it reminded her of similar 'propaganda parades' in her home country, designed to make people feel compliant and positive about the Communist party state. A German participant said it filled her with fear, evoking stories she had heard from elderly family members about horrors under Soviet occupation at the end of the Second World War. A UK participant, perhaps with the spirit of Brexit still reverberating fresh in the background, said she found the enforced uniformity and conformity disturbing. A Filipina participant from an Hispanic cultural background, who had lived under a repressive military dictatorship, said she liked how the soldiers were as-if dancing to a rhythm and doing something constructive that displayed positive talent. I noticed banners in the background depicting 1941, the year in which the Nazis had unleashed a war in the East that resulted in unspeakable terror and devastation. As a passionate anti-Nazi, I saw the march as an assertive symbol: a 'never-again'. We reflected on our different selective perceptions, feelings and interpretations and the profound influence of ourselves-as-filters as we look out onto the world. In a similar vein, at a Gestalt coaching training workshop last week, I posted an image on screen of a tree in wheat field with dark clouds looming overhead. I asked the group what they would notice in 3 imagined scenarios: 1. As a child, you loved to climb trees; 2. You are walking the countryside and have forgotten to bring a raincoat; 3. You and your family have had no food to eat for a week. We noticed that we notice what matters to us in the moment. Different people-groups may notice different things in the same situation, or the same person-group may notice different things in the same situation at different times. We attribute meaning based on our beliefs, values, hopes, fears and expectations. This includes personal and shared-cultural memories, emotions and imaginations. As we move ahead this year, I pray that I-we will do so with eyes wide open. What may appear to us as self-evident, real and true may reveal as much about us as who or what we observe: if we are willing to see it. What can we do to create greater critical reflexivity? How can we address blind spots and hot spots to open up fresh possibilities, address risks – and take a stance that is sound? ‘My English is terrible,’ he said, despondently, in near-perfect English. ‘I feel like I’m going backwards rather than improving.’ This recent, brief conversation with an asylum-seeker student typified a phenomenon that leaders, coaches and trainers often encounter in people and groups. A German social worker friend describes it as: ‘Eine Frage der Wahrnehmung’, which is, translated, ‘A question of perception.’ It’s something about perspective, belief what we notice and how we construe it. In this vein, Dr. Terrence Maltbia commented astutely in a LinkedIn post this week that coaching and facilitation are ‘as much about mind-sets as skill-sets.’ This student (above) was far more competent, more skilful, than he realised. Yet his own assessment of his performance affected his confidence badly. This, in turn, affected his emotional state and what he believed himself capable of doing. The immediate coaching challenge was, therefore, to address his mind-set, not his language skills. I asked and gestured: ‘Imagine a box. The box contains everything you know in English. How big was the box when you arrived in the UK?’ He gestured the shape and size of a tiny box. ‘And now..?’ He gestured a significantly larger box. ‘And so..?’. A wide smile broke out on his face. He sat up straight and his voice became stronger as he spoke: more confident, able and hopeful. In that moment, his perspective had changed and everything had changed with it. Eine Frage der Wahrnehmung. Why is this important? A person’s performance at work can be regarded as a dynamic product of 4xCs: commitment, competence, confidence and credibility. Commitment: what we are willing to do; competence: what we are able to do; confidence: what we believe about ourselves; credibility: what others believe about us. In my experience, confidence is a critical recurring factor in enhancing or inhibiting a person’s effectiveness. So, I’m curious: how do you enable a change in perception? I was reminded recently of one of my sister’s ex-boyfriends in our teenage years. The lad was called Tom and, one day, he decided proudly to have his name tattooed on his neck. When he got home, however, he was dismayed to look in the mirror and read ‘moT’. ‘I can’t believe they spelt my name wrong!’, he exclaimed in near despair. My mother looked on in near despair too. How could her daughter be going out with this guy?? My sister laughed but poor Tom just looked puzzled. I can hear so many satirical expressions immediately coming to mind: ‘Not the sharpest knife in the drawer; A few sandwiches short of a picnic; Proof that evolution can go in reverse’, etc. It’s as if we’re a lot brighter than Tom, less prone to such stupid mistakes. Tom misinterpreted what he saw but we see and understand things more clearly. Perception is reality and Tom needed a reality check. We’re not that easily tricked or confused. We’re not like Tom. We see things as they are. That is, until we read books like David McRaney’s ‘You Are Not So Smart’ (2012). With a wide range of disarmingly simple-yet-profound examples, McRaney describes a whole host of ways in which we unknowingly and convincingly delude ourselves, pretty much every day. Alex Boese concludes on the back cover: ‘Fascinating! You’ll never trust your brain again.’ It’s as if the assumptions we hold about what is real and true about ourselves, the world, life and relationships need to be held…lightly. Yet this poses some serious existential, ethical and practical challenges. Who or what are we to trust if we’re not sure what’s real or true? Who or what are we to take a stance on if we’re not sure if the ground we’re standing on is sound? Faith, doubt and belief come face-to-face with diverse related fields, e.g. social constructionism and Gestalt. This is rich territory for deep coaching, leadership and OD. So, tell me - what are your experiences of working with certainty and uncertainty, ambiguity and trust? It was great fun to work with a professional cartoonist. Bill Crooks has a remarkable gift for capturing, expressing or stimulating a thought, an idea or a feeling with a few quick strokes of a marker pen. We were leading a workshop that aimed to reveal and challenge the assumptions that participants bring to customer, client and beneficiary relationships. Bill quickly sketched a large person looking down at a small person through a magnifying glass. He then asked the group, simply, ‘What do you see?’ Participants looked down, thought, discussed then spoke up. ‘We – the organization – are the large person. We are scrutinising the client.’ The inference here was that the organization holds the power, the influence, the prerogative to evaluate and to choose. The wider group agreed. Bill responded provocatively, ‘And what if, unknown to us, the client is connected to unseen networks that dwarf the power, the influence, the prerogative of our organization? Who now is looking down on who?’ It was a sobering moment. Silence hit the room. How easily we make assumptions about ourselves, about others, based on what we see, know or think we understand. Imagine, for a moment, the leader who believes that he or she holds far greater power and influence than individual front-line staff. Hold that thought. And now: think of front-line staff who are connected by social media to key networks and influencers in the organisation’s wider arena. Who now is looking down on who? We are talking here about the dramatic power of re-framing. As we change the metaphorical frame through which we view a person or situation, different pictures, perspectives, opportunities and challenges can emerge, change colour/shape or come into sharper focus. Shift the frame, shift what appears, how it feels and what options become available to us and to our clients. What have been your best experiences of reframing or achieving a radical paradigm shift? How did you do it? ‘I know you think you understand what you thought I said but I'm not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.’ ‘I guess I should warn you, if I turn out to be particularly clear, you’ve probably misunderstood what I said.’ (Alan Greenspan) You may have had that experience of communicating something you thought was perfectly clear, only to discover that the other person got the completely wrong end of the proverbial stick. How is that possible? Was it something in what you said or, perhaps, how you said it that influenced how the message was received, distorted or misunderstood? Whatever the cause, when it does happen, you can both feel bemused, confused or frustrated – and the consequences can be difficult, damaging or dangerous. I want to suggest this occurs mainly as a result of mismatched beliefs, values, assumptions and emotions in four critical areas: language, culture, context and relationship. There are, of course, situations in which a person may wilfully misinterpret what you said or simply choose to ignore you. However, I’m thinking more here about when it happens inadvertently and out of awareness. It’s something about what influences (a) what we infer and (b) how we interpret, when we communicate – so that we can improve it. The language question means the same words can mean different things to different people, even in the same language group. The culture question means the assumptions I make appear obvious or self-evident in the groups or teams I belong to. The context question means I interpret what you say based on my own perspective and understanding of the situation. The relationship question means I filter what you say based on what I perceive and feel about the nature, dynamics and quality of our relationship. So – this where a spirit of inquiry can help: Check what the other has heard and understood. Notice the language they use. Be curious about their cultural and contextual perspectives. Sense how they are feeling. Build trust. I had a friend once, Norman, who was deaf and had tunnel vision – literally. He was able to see people and things directly in front of him but had no peripheral vision at all. If I wanted to gain his attention, I had to stand directly in front of him to sign. As I approached, I had to be careful not to take him by surprise, as if suddenly appearing out of nowhere. It was a tough lived-experience for Norman and made navigating the world and relationships very challenging. I admire his courage in how he handled it.

In common use, we apply the phrase ‘tunnel vision’ metaphorically to represent a person or group’s psychological state. It tends to be characterised by limited focus or perspective, lack of awareness of the bigger picture and unwillingness to consider alternative points of view. As such, we normally associate tunnel vision negatively with narrow-mindedness, a condition to be avoided or challenged. We need to think more openly, broadly or laterally if we are to be effective…or so we assume. Yet there are other dimensions to tunnel vision. Think of blinkers or blinders that enable a horse to focus on straight ahead by excluding a wider view and, thereby, to avoid it becoming distracted or alarmed by things around it. Think of choosing to focus intently and single-mindedly on a vision or piece of work in order to fulfil it, complete it to a certain standard or achieve it within a given timeframe. There are times and situations where tunnel vision serves us well to achieve our goals. There are aesthetic dimensions too. I walked along a train platform this week and noticed a beautiful snowscape through a porthole window. I was struck by how the window framed the view in such a way that it drew my attention to things I had never noticed before. It was as if I saw them simultaneously out-of context and in-new context, like how we see special qualities in a person, how he or she now stands out from a crowd, when we fall in love. So...as we approach 2018, is there light at the end of your tunnel? Take a clean sheet of flipchart paper. Draw a small black dot in the middle. Ask people what they see, what they notice. Almost invariably in my experience, people will say, ‘A black dot’. I haven’t yet heard someone say, ‘A white sheet of paper’. I first saw this used in an anti-racism workshop. The tutor, Tuku Mukherjee, used it as a metaphor for how we tend to focus our attention on minorities in society and ignore or don’t even see the majority. The backdrop is, in effect, invisible to us.

In this example, the backdrop forms the context for the ‘minority’. In other words, ‘minority’ only has meaning vis a vis a perceived ‘majority’. I heard one astute black speaker say, ‘In the UK, I am viewed as an ethnic minority whereas, when I look across the world as a whole, I see that I am part of an ethnic majority.’ So what we see, what sense we make of it, is contextual. To understand what we notice, we sometimes need to shift our focus to the background against which it stands out. Take, now, an example of a person who is ‘underperforming’ at work. This definition of the situation locates underperformance in the person, as if it represents a quality, aptitude or behaviour of the person him or herself. It leads us to consider how to improve the person’s performance, e.g. through mentoring or training. All things being equal, this may improve the person’s performance and, if so, we may view the situation as resolved. ‘X was underperforming…X is now performing…sorted.’ Yet what constitutes ‘good performance’ is defined by the backdrop, the wider organisation. What if performance expectations are unrealistic? What if the person does not have sufficient resources, guidance or support? What if systems, policies or procedures are such that they make the person’s work untenable? What if relationships or power dynamics are culturally toxic? What if instances of ‘under-performance’ form a repeating pattern in this organisation or team? Step back…look…see. We were talking about focus in leadership and coaching and my colleague, Pav, looked at me intently and said, quite simply, ‘Keep your eye on the squirrel!’ It did make me laugh. It’s a fun, colourful image that cautions us to stay focused, to avoid getting side-tracked, to beware of – like Alice in Wonderland – falling down proverbial rabbit holes (if you can forgive the mixed metaphor). Or to quote guru Stephen Covey: ‘The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.’

I can see the sense in this. If we work to achieve a vision, to fulfil a strategy, it can enable us to be effective and efficient, to prioritise and reach goals. It can also help us to avoid dissipating energy, wasting resources. It’s a reason why, when coaching, I will ask clients questions such as, ‘What are we here to do?’, ‘What are you hoping for?’, ‘What is possible if we do this well?’, ‘What would a great outcome look and feel like?’, ‘How will we know when you have reached it?’ The flip side is that we can become so focused, fixed, planned, organised, that we may miss all kinds of serendipitous adventures and emergent opportunities that arise. A friend, Rob, commented on this recently: ‘When we look back in life, many of our best relationships and experiences came as a result of things which, on the face of it, at the time, appeared to go horribly wrong.’ A question for leaders, coaches and clients could be: how to be well-focused – and yet open to the potential of each moment? Finally, what appears to us to be 'the main thing', the most important thing, depends a lot on what we believe, our values, how we are feeling, our cultural paradigm and what frame of reference we adopt. A shift in language, perspective or circumstance can change the whole way in which we view and construe something or someone. A related challenge for leaders, coaches and clients may be, therefore: how to keep our eyes on the squirrel – without becoming blinded or fixated by it..? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed