|

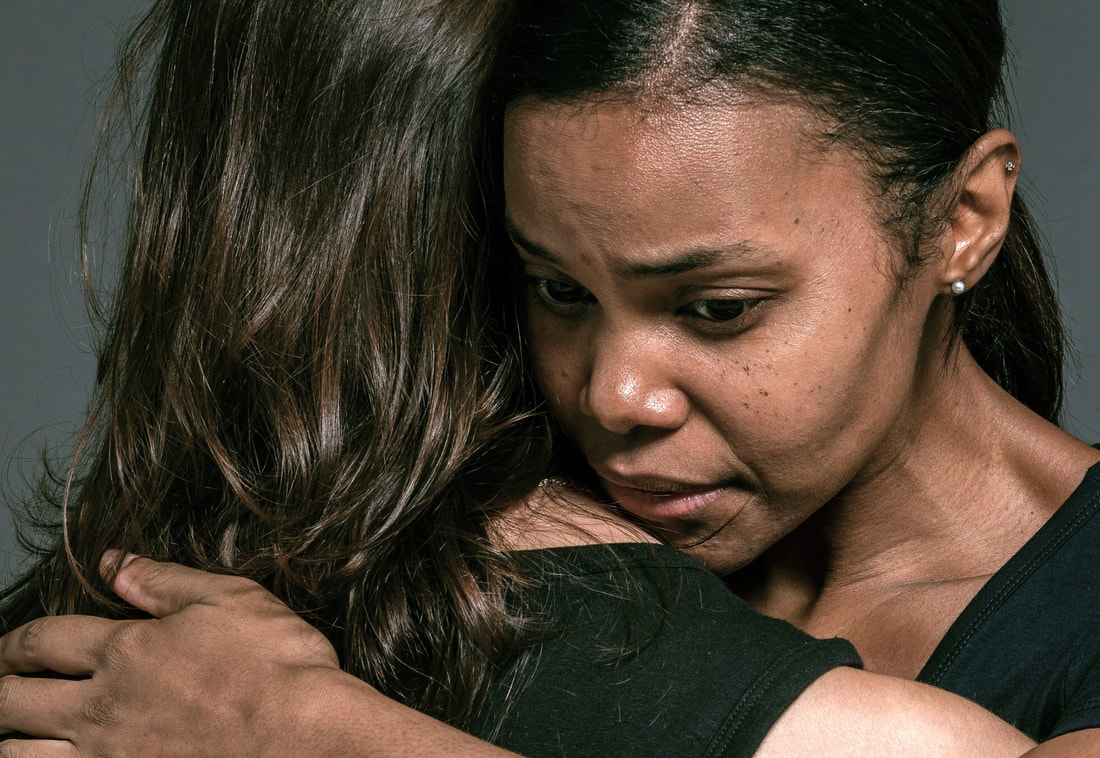

‘Empathy is the starting point for creating a community and taking action.’ (Max Carver) I had a long conversation with a Kurdish-Iranian man recently about his experience as a refugee in the UK and the ongoing wait for news that his wife will be allowed to join him here. With a warm smile of anticipated relief, he shared his hopes of building a new life in this country where he and his wife can finally feel safe and free. Yet then he touched his heart with his hand and his face shifted to a pained expression. He shared his sadness that he can never feel truly happy and at peace, knowing the oppression that his family, friends and neighbours are still living under in his home country. I was moved by his empathy and, at the same time, impressed by his stance that under such difficult and protracted life circumstances, he had not become so focused on his own situation that he had lost sight of others. It is, after all, a human risk that, when faced with challenges such as high anxiety and stress, our survival instinct can take over and turn us in on ourselves, absorbing us with our own needs and interests – a bit like when the body reacts to an external shock or threat by diverting its resources inwards to protect its vital organs. It’s a form of defensive flight to save ourselves first. How do you hold onto empathy...to love...when natural instinct may push or pull you to withdraw?

14 Comments

‘The final frontier may be human relationships, one person to another.’ (Buzz Aldrin) I met recently with small groups of asylum seekers and refugees from the Middle East and Central Asia. All commented on how grateful they are for the practical help they have received from the host countries in which they have settled in Europe – housing, health, education etc. and money for food, lighting, heating, water, clothing etc. Without such basic necessities, they could not have survived. That said, their sense of isolation, so far away from home, family and friends etc, can be very painful to endure. Sometimes, having escaped persecution, conflict or war, they may feel anxious or reluctant to connect with people from their own countries of origin, in their host countries, because they may be from ‘the other side’. It’s hard to trust if trust has been absent, damaged or betrayed. I ask what they need, what they hope for, what would be life-giving, more than just bearable. Their answer is simple and clear: human relationship, friendship, laughter, to be listened to, to feel heard and understood. Sometimes they lack confidence to reach out. They may fear rejection, feel insecure about their limited local language or worry about a risk of cross-cultural misunderstandings. Host countries may risk focusing so much on strategy, policy and task that they lose sight of relationship. I’m inspired by Pete in the UK and Margitta in Germany. They are followers of Jesus. Whenever we encounter people who are asylum seekers or refugees, Pete and Margitta are welcomed with huge smiles. They see and treat people, warmly, as real people. Love is transformational. 'Home isn't where you're from, it's where you find light when all grows dark.' (Pierce Brown) I was invited yesterday to meet with a family of asylum seekers who have recently arrived in Germany from Syria. They are living in temporary accommodation, a house with no furniture, only mattresses on the floor, yet at least in a place of safety until suitable accommodation is found. The three young children greeted us excitedly with wide grins when we arrived at the door. My hostess, Margitta, a Christian activist with a passion for the poor and most vulnerable, had brought a travel cot in preparation for the arrival of the family’s new baby. As we sat on the floor together, the father pointed to himself apologetically and said, ‘No German’, then to us, ‘No Arabic.’ At that moment, some simple words and phrases I had learned some 40 years ago whilst working briefly in a Palestinian hospital came tumbling into my mind. I felt unsure if I had remembered them correctly, and a bit nervous that my English-accented Arabic might sound a bit weird, but nevertheless spilled them out: ‘Hello, How are you? Fine thanks. Please. Thank you. Yes. No.’ Etc. At least that’s what I think I said. Not exactly the stuff of fluent conversation. Yet, in that moment, the whole family looked stunned…then absolutely delighted…then with huge smiles burst into a spontaneous applause. When arriving in an alien land where so much is so unfamiliar, to hear simple words spoken in one’s own language must feel like a reassuring familiarity, a comforting reminder of one’s own home. I sensed it mattered, too, that my own stumbling German made them feel less isolated, less alone. Small things can be big things. Our weakness can be our strength. In its now-classic album, Hemispheres, Canadian rock band, Rush, sing a dramatic story of a cosmic struggle between competing gods of love and reason; each determined to rule humanity on its own terms. It’s a creative mythological account of the very real dilemmas and tensions we face and experience in human decision-making of head vs heart. (If interested in a faith dimension, we can see this polarity resolved in Jesus, described in the Bible as ‘full of grace and truth’, and in his call to be ‘wise as serpents and tame as doves’). Yet, how hard it is to do this in practice. It becomes more complex if we get caught up in emotional reasoning: ‘…the condition of being so strongly influenced by our emotions that we assume that they indicate objective truth. Whatever we feel is true, without any conditions and without any need for supporting facts or evidence’ (Therapy Now, 2021). It’s a blurring of heart and head so that the former appears to us, as if self-evidently, the latter. Betts and Collier, in their thoughtful review of refugee policy (Refuge, 2017) liken this to a ‘headless heart’; a decision driven by emotional response without due regard for consequences. A person may hold the opposite extreme, the ‘heartless head’, where he or she believes every decision must be informed or supported by rational thinking or objective evidence - and emotion or intuition are disregarded as irrelevant or unsound. We see this in cultural environments where, as Eugene Sadler-Smith observes, leaders feel compelled to post-rationalise intuitive decisions in order to make them more acceptable to colleagues (Inside Intuition, 2007). It’s a stance that risks dismissing beliefs, values and other dimensions of sense-making, motivation and experience. John Kotter brings words of wisdom here (Leading Change, 2012): to pay attention to our own default biases and to take account of those of others too, if we’re seeking to influence change. On presenting vision, he offers a helpful rule of thumb, ‘convincing to the mind and compelling to the heart’. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) provides useful insight into different preferences that influence decision-making too. Rush’s epic song ends with its own solution: ‘Let the truth of Love be lighted, let the love of Truth shine clear…with Heart and Mind united in a single perfect sphere.’ |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed