|

‘When you wish upon a falling star, your dreams can come true. Unless it’s a meteorite hurtling to the earth which will destroy all life. Then you’re pretty much hosed no matter what you wish for. Unless it’s death by meteor.’ (Despair.com Demotivators) I was surprised to return to my desk and find 6 people waiting in a queue to complain. I’d worked hard on my all-staff presentation and thought I’d handled it well. My task had been to present the results of an annual staff survey: the good, the bad and the ugly. I’d attempted to present a view that, even in those areas where scores were low, such scores represented implicit positive hopes and aspirations. If, for instance, someone had given a low score for quality of management, it was because good management matters to them, even if their desires and expectations were unmet. My agitated colleagues saw it differently. They felt as if I had spun the results, put a positive spin on the ugly, with a result that those staff who had already been angry, frustrated and disappointed now felt even more strongly that their voices were ignored, dismissed and unheard. Still taken aback, I tried to defend myself, arguing that it wasn’t spin but a matter of perspective. They weren’t having it, and they pushed back even harder than before. I was left reeling and confused. In my mind, I had presented the survey results with integrity. I couldn’t understand their hurt and angry responses. This was some years ago and I remember vividly, some days later, driving into work when a penny dropped suddenly. It occurred to me that, when a person describes a glass as half-empty, it’s not simply a matter of perspective but one of sentiment and emotional experience too. By presenting a glass as half-full, I had inadvertently failed to acknowledge and represent an authentic expression of how they were feeling. I returned to my colleagues and shared this somewhat embarrassingly-belated self-revelation – with which they wholeheartedly agreed. They accepted my apology with grace.

25 Comments

‘The question is: how to ensure a healthy life-life, work-work and life-work balance?’ It felt like losing the plot. Spinning plates isn’t unusual or new yet, as a freelancer, the tell-tale signs were beginning to show. I met with my coach, Sue, to re-ground myself and my work before, like some scene from a Greek wedding, plates began to fall and smash in pieces around me. Sue asked me, ‘If you were to conduct an appraisal of your life and work for the past 12 months, what would the highlights be? How would you rate your life and business health and performance?’ My mind immediately went blank. I had allowed myself to become so busy that the year was a total blur. So, I sat down that evening, took out my diary and created a simple summary. I discovered to my surprise that I had worked with people from 150 organisations (charities; NGOs; churches; public sector, e.g. social services, health, education, police); from 35 countries; 60 coaching sessions; 30 training workshops; 25 action learning set meetings; written 25 articles and blogs; provided ad hoc TESOL support for refugees and asylum seekers; and, by God’s amazing grace and the generosity of family and friends, sent £23k in support to the poorest and most vulnerable in the Philippines. Strikingly, until I did this review, I had no idea. I had lost sight and sense of the wood in the midst of the trees. So, Sue asked me next what I enjoy most about this kind of work-life that I choose to live. I responded, ‘A sense of purpose as a follower of Jesus – and freedom.’ She came straight back with a challenge: ‘Where, for you, is the boundary between freedom and chaos?’ That hit the nail on the head, hard. Freedom is, for me, tied up closely with choice. I was at risk of becoming reactive, falling backwards. I needed to regain my balance, my grounded stance, to be truly free to choose again. Sue offered a suggestion. ‘How would it be if you were to set aside periodic ‘Creating Freedom’ days in your diary – to do those things (apart from your work) that you find life-giving and will help keep you grounded; or that will drain away your life and perspective if you don’t do them?’ That was a great insight and idea. That evening, I marked out spaces in my calendar for silent prayer, physical exercise, time with family and friends, holiday breaks; and for doing the headache-inducing financial and administrative parts of my life-work that I would otherwise procrastinate over or subtly avoid. That was my confession and solution. How do you ensure a healthy sense of purpose, perspective and priority in your own life and work? ‘Good endings make sense, evoke emotions like contentment, anger, sadness, or curiosity, shift the person’s perspective or open her mind to new ideas. Good endings bring the person to some kind of destination.’ (Alex J Coyne) Lilin Lim, my sister-in-law, reads the back page of a novel first to decide whether it looks like the story is worth reading. There’s something about a good ending that can make whatever went before it feel worthwhile – the time, effort or, at times, struggle to get there. Think back to your own life and work peak experiences: e.g. birth of a child, achievement of a desired promotion or qualification, overcoming of a disability or fulfilment of a dream that, perhaps, felt hard at the time yet worked out well in the end. Conversely, think back to seminars, workshops or meetings you have taken part in that didn’t result in anything remotely meaningful to justify the investment. Academic Peter Cotterell commented satirically that, similarly, many lectures and articles can feel like, ‘a plane in the sky that takes off well yet finds itself circling in the clouds and can’t find a way to land.’ Stephen Covey said, ‘Begin with the end in mind’, a perspective that resonates well with the biblical idea of an end-revelation to draw us forward. This same principle applies in coaching and action learning. If we open a conversation with questions such as, ‘In relation to X, where do you want to be an hour from now?’ or ‘Of all the things we could spend the next hour doing together, what, for you, would make this time well spent?’, it can help ensure an explicit sense of focus and purpose from the outset – and raise into critical awareness Gary Rolfe’s movement towards an ending: the ‘Now what?’, before considering the ‘What?’ and the ‘So what?’ David Clutterbuck suggests ending this type of conversation with an invitation to the client to reflect and summarise for him- or herself, using a simple 4xI framework: ‘What are the Issues we’ve talked about; what are the Insights that you’ve had; what are the Ideas that we’ve generated; what are your Intentions now?’ It’s a consolidating technique that can enable a sense of learning and closure for the client and a transition into action. It helps to avoid the risk of a session simply...fizzling...out. Rosie Nice poses useful grounding questions: ‘Are there any other dimensions you would like to explore before moving into actions? Would it be helpful if we were to consider some questions to help you think through what actions you might take? What’s the main thing you are taking away, having had opportunity to think this through?’ Sue Murkin ends with: ‘Given what you know now, how will this impact on your work? How could you see yourself using this? What will you do now?’ How do you avoid perpetual drift or an abrupt crash landing? How do you create a good ending? A ‘check engine’ warning light flashed up on my car dashboard this week. It turned out to be a false alarm – a warning that was, apparently, triggered by jump start last week. I know that now. The unnerving part was the not-knowing in-between. What is there was something seriously wrong? How am I to know if a warning symbol can be ignored or if it’s highlighting a genuine cause for concern? In this case, I was able to take the car to a local mechanic to have it checked out. When, however, we experience ‘warning lights’ psychologically or emotionally, it can be harder to discern. A manager is invited to present to an Executive Team and feels deeply anxious. Is that a false alarm or, perhaps, an intuition that is flagging up what ought to be considered a genuine risk? A team member is asked to give critical feedback to a colleague in another department and feels worried about how they may react. Are they being over-sensitive or should they be concerned? Here are some insights to help when making a judgement call. 1. Has the person experienced similar situations and associated emotions in the past? If so, their past may be re-triggering feelings in the present. 2. Does the person have any tangible evidence that supports their concerns? They may be making hypotheses or assumptions. 3. Would different others be likely to feel the same if faced with a similar situation? It may be a personal or cultural narrative the person is telling themself. A tricky part is that it’s not always an either-or phenomenon. The anxious manager may have experienced something similar in the past and the Executive Team may be demanding unrealistic levels of performance. The team member may be highly-sensitive and their colleague may react defensively. How do you distinguish between a false alarm and something that’s real? Do you trust your your feelings or intuition most, or lean more towards evidence or reason – or something else? In times of perceived crisis, the lines between coaching and therapy can sometimes feel more blurred than usual. This is because the kind of issues that people bring to coaching may touch on more personal dimensions and at a deeper level than they would normally. The Coronavirus and the intense drama that surrounds it is a case in point. People may find themselves not only, say, dealing with the impacts of lockdown on their business and work, but also anxieties they hold for the health, safety and well-being of their family, friends and colleagues. So here are some insights from four psychological fields to help coaches enable people to navigate such times and experiences. First, Gestalt. Notice if and when a person is fixated on one specific dimension of what is taking place, as if that is the only dimension. A vivid, current example is the mass media’s fixation on the number of people contracting or dying from the Corona virus – to the exclusion of attention to a far, far greater number of people who haven’t contracted the virus and who haven’t died from it. It can create the impression that everyone is contracting the virus and that everyone is dying from it. If, therefore, you notice a person becoming overly-preoccupied by one dimension of an issue, acknowledge the underlying feeling (e.g. anxiety) and enable him or her to notice what they are not-noticing. Second, Existential. The Corona crisis has evoked deep fears, particularly in wealthier countries where people and communities are no longer used to facing these levels of perceived vulnerability and threat. Dramatic soundbites in social media, claiming this is the worst crisis the world has ever faced, add to the sense of fear and alarm – that death and destruction of people, communities, organisations and social systems are imminent. Whilst such apocalyptic visions ignore previous and arguably far-worse crises (e.g. Bubonic plague; Spanish flu; Two World Wars), the coach can use this opportunity to enable people to explore their deeply-held beliefs, values and stance in the world. Third, Psychodynamics. People, groups, organisations and communities experience the present through the emotional, psychological and cultural filters of the past. People will very likely have experienced crises of one sort of another before that from their standpoint and experience ended badly or, conversely, worked out well in the end. Such experiences will influence what the person perceives, how they feel about it and how they will respond to a crisis now. If you notice a person reacting very strongly, particularly if it appears disproportionate or out of character, acknowledge the feeling and explore how it may be reverberating with experiences from that person or group’s past. Fourth, Social Constructs. People create personal and cultural narratives that give focus and shape to their experiences and, thereby, enable people and groups to make sense of them. So, for instance, politicians, health professionals and the media are, currently, presenting very specific versions of events in relation to the Corona crisis. They are construing facts, stories and images selectively to convey a particular narrative that will lead to a certain response; whether that be e.g. to engender public confidence, influence public behaviour...or sell more newspapers. Listen carefully to the stories people are creating and using and, where helpful, enable them to construct a healthier narrative. Can I help you with navigating a crisis? Get in touch! [email protected] For the first time in human history, toilet paper is worth more than real money. It’s hard not to look on with bemusement and alarm at the wild antics of desperate people, fighting in wealthy supermarket halls to grasp hold of the last packs of loo roll. My Filipino friends are utterly astonished. Whilst poor people there are struggling to hold onto their income, their ability to feed their families – and with good reasons too, here we are gripped by a selfish fear of…inconvenience. The new pandemic has its scary dimensions, but they are nothing compared to those created by sheer irrationality – whipped up into a frenzy by irresponsible, scare-mongering media, fueling the flames of terror. At times like this, we need to look outwards, not barricade ourselves inwards, to see how best we can support those who are poor and vulnerable; locally, and in the wider world. An antidote to the disease, that risks taking so much, is a yet greater and deeper humanity – to help ourselves and each other by keeping things in perspective; to see people in need and take practical, caring action in response; to pray for faith, hope and love when afraid or tempted to retreat, grab or lash out. Ask: ‘When you look back, what kind of person do you want to have been?’ Then be it…now. Are you feeling gripped by the Coronadrama? How can I help you? Get in touch! [email protected] ‘It’s front-to-back!’, my daughter would say with a smile – when she was two. It was creative genius, depicting the meaning of the phrase, back-to-front, in how she structured the sentence itself. It’s a word play suggesting that something is, somehow, the wrong-way-round. This notion of wrong-way-round itself suggests implicitly that there is a right-way-round. Our notions of right-way-round are usually an indicator of convention, function or perspective rather than something that is, per se.

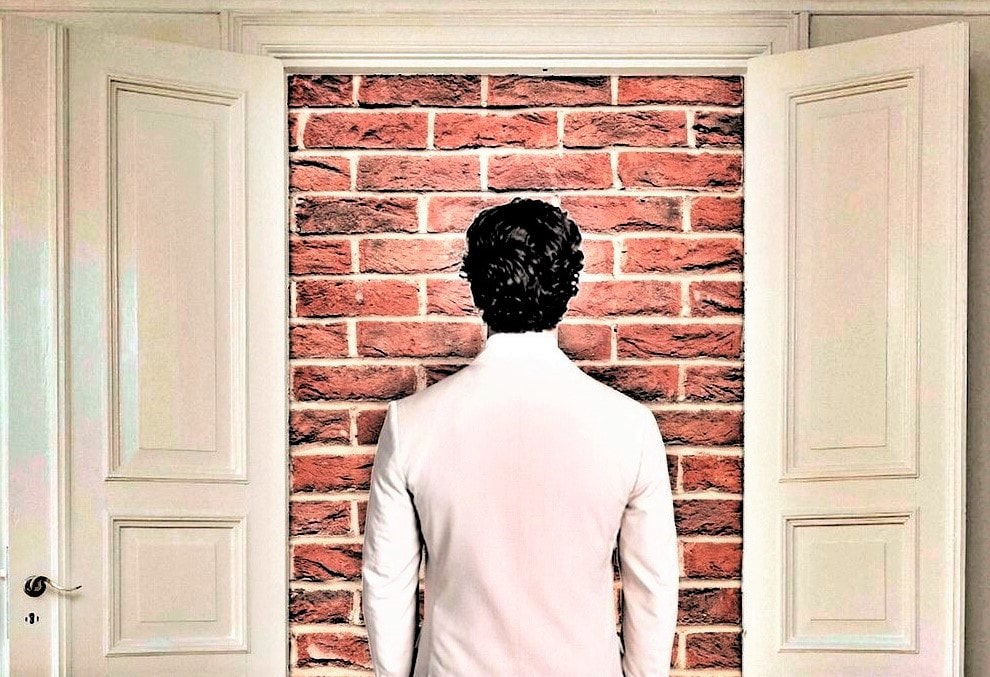

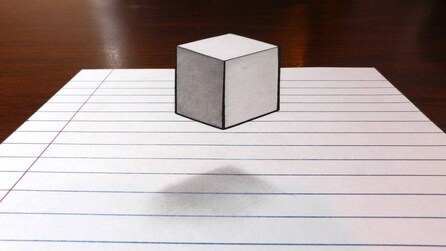

Take, for instance: ‘The West is in the East if you’re standing in Vladivostok.’ The statement only makes sense if we hold a Eurocentric view of the world, in which countries on the left of a flat, traditional map are regarded as the West, corresponding to directions on a compass, and those on the right are (progressively) East. If we form the map into a globe, however, everywhere is relatively West and East of everywhere else, marked only in relation to other places by relative direction and distance. We could instead take, say, a geo-political view in which places are distinguished or related by location, terrain, access or resources. Or we could take, say, a socio-anthropological view in which places are distinguished or related by history, tradition, language and culture. There is no one, definitive, way of looking at and making sense of what is in the world. Whatever statement I make reveals an implicit personal-cultural construct; a hidden backdrop of beliefs, values and assumptions. How easy do you find it to view things front-to-back at work, to notice, reveal and challenge existing paradigms and perspectives? If you do it well, what then becomes possible? Do you need help with front-to-back thinking? Get in touch! nick-wright.com 'Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for life. Right? Wrong. Not if there’s a factory upstream pumping toxic effluent into the river.’ (Bill Crooks) Bill’s jolting critique demonstrates starkly the potential inadequacy of focusing on a person, or an issue, out of context. There is, after all, always a context, a Gestalt ‘Ground’, that bears an influence on a person, team, group or organisation and what she, he or they are capable of achieving. It could be an enabling or disabling influence, a stronger or weaker influence, yet an influence all the same. I worked with an organisation that took contextual dynamics very seriously; e.g. when setting and reviewing goals, ‘What else?’ was a key question. What else would it take to achieve success, over and above the enthusiasm, expertise and hard work of the individual? What people, resources, relationships and other factors would she have to navigate well, and what support would she need? This approach raises some interesting questions. If we take this kind of systemic view, to what extent does it make sense to reward (or reprove) an individual if the wider context plays such a significant influence on what he does, or doesn’t, do or achieve? It is something about how well, or not, he grasps, transcends or overcomes whatever opportunities or challenges the context may create? What do you think? Can I help you develop greater systemic awareness in your work? Get in touch! [email protected] Thinking out of the box sounds good in principle yet can be difficult to do in practice. What if, say, you are the box, or you don’t know you’re in a box, or you can’t see the box? What if others you’re working with are in boxes, or don’t know they’re in boxes, or want to put you in a box, or don’t like your box? I was asked once to coach and mentor an HR colleague who needed to learn to think outside of the box. I asked for clarification. It turns out they meant that she lacked, yet needed, strategic thinking and systems thinking for her role. She looked at me blankly. She couldn’t see what she couldn’t see. I wondered how to enable her to make a shift to conceptual (‘strategic’, ‘systemic’) from practical; to abstract ideas from concrete examples that she could work with and learn from. She described herself as a detail person, trained to spot the critical points in the micro, e.g. salary spreadsheets so that reports were accurate and errors were avoided. I decided, therefore, to start with an example in the micro and to work out from there to a wider macro. This, I hoped, would gradually bring wider systemic and strategic issues and perspectives into view and highlight the links between them. I invited her to bring an example from her work. She chose an email from a client in her business partner role. It raised a query about how to deal with a performance issue in his team. She had been about to respond to the email with advice on performance management policies and procedures. I invited her to draw a small box on a large, blank sheet of paper and to draw the person inside the box who was to be performance managed. I then invited her to draw a larger box outside of that box and to draw anyone or anything in that box that could be influencing the person’s performance. As she considered this, various issues and key people came to mind. She wrote them in the box. I asked, ‘What might these different stakeholders hope you will take into account in addressing this?’ She jotted down those thoughts too. I then invited her to draw an even larger box around that one…and repeated the process until we had reached external stakeholders, opportunities and risks and future horizons. At each stage, she was able to consider significant questions and intervention options. It brought a wider picture into view so that she could see it. How do you deal with boxes? Do you need help with thinking out of the box? Get in touch! [email protected] ‘My English is terrible,’ he said, despondently, in near-perfect English. ‘I feel like I’m going backwards rather than improving.’ This recent, brief conversation with an asylum-seeker student typified a phenomenon that leaders, coaches and trainers often encounter in people and groups. A German social worker friend describes it as: ‘Eine Frage der Wahrnehmung’, which is, translated, ‘A question of perception.’ It’s something about perspective, belief what we notice and how we construe it. In this vein, Dr. Terrence Maltbia commented astutely in a LinkedIn post this week that coaching and facilitation are ‘as much about mind-sets as skill-sets.’ This student (above) was far more competent, more skilful, than he realised. Yet his own assessment of his performance affected his confidence badly. This, in turn, affected his emotional state and what he believed himself capable of doing. The immediate coaching challenge was, therefore, to address his mind-set, not his language skills. I asked and gestured: ‘Imagine a box. The box contains everything you know in English. How big was the box when you arrived in the UK?’ He gestured the shape and size of a tiny box. ‘And now..?’ He gestured a significantly larger box. ‘And so..?’. A wide smile broke out on his face. He sat up straight and his voice became stronger as he spoke: more confident, able and hopeful. In that moment, his perspective had changed and everything had changed with it. Eine Frage der Wahrnehmung. Why is this important? A person’s performance at work can be regarded as a dynamic product of 4xCs: commitment, competence, confidence and credibility. Commitment: what we are willing to do; competence: what we are able to do; confidence: what we believe about ourselves; credibility: what others believe about us. In my experience, confidence is a critical recurring factor in enhancing or inhibiting a person’s effectiveness. So, I’m curious: how do you enable a change in perception? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed