|

‘We're fascinated by the words – but where we meet is in the silence behind them.’ (Ram Dass) I remember my first experience of haggling over the price of a leather belt in a Palestinian marketplace. I was a teenager at the time and I found this approach to buying and selling novel and entertaining. The smiling street vendor played the game skilfully. I asked, ‘How much?’ to which he responded, '$6.’ ’$6?’ I replied, ‘I could get the same belt at another stall for $1. How about $2?’ ‘$2?’ He replied, ‘Please don’t insult me. It cost me more than that to make it. As a special deal, however, I’ll give it to you for $5.’ ‘$5?’ I replied, ‘The most I would pay for it is $4.’ ‘$4?’ He replied. ‘Don’t you realise I have a family and children to feed?!’ He grinned. We closed at $3. To a Westerner, where buying and selling is typically more transactional than relational, this toing and froing can feel like a manipulative game; frustrating, bordering on dishonest and time-wasting. That’s mostly because we tend to miss the underlying cultural meaning and purpose to this type of engagement. I met recently with an international team from USA, Netherlands, Jordan and South Africa. They are part of a Christian organisation and were keen to identify and work through some cross-cultural and relational challenges. I decided to share a short passage from the Bible with them, then to invite them to discuss what sense they made of it: “Jesus withdrew to the region of Tyre and Sidon. A Canaanite woman from that vicinity came to him, crying out, ‘Lord, Son of David, have mercy on me! My daughter is demon-possessed and suffering terribly.’ Jesus did not answer a word. So, his disciples came to him and urged him, ‘Send her away, for she keeps crying out after us.’ He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.’ The woman came and knelt before him. ‘Lord, help me!’ she said. He replied, ‘It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.’ ‘Yes it is, Lord,’ she said. ‘Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.” And now to the critical closing: “Then Jesus said to her, ‘Woman, you have great faith! Your request is granted.’ And her daughter was healed at that moment.” (Matthew 15:21-28) To the Westerner who views language and transactions in literal, linear, straight lines, Jesus’ initial responses to the woman are shocking. We take his opening action as his definitive stance. We don’t see the smile on his face or the glint in his eye, or understand the movement as the interaction progresses. We may assume the story is written to affirm the woman’s perseverance. We may think she has changed his mind. We are likely to miss the Semitic ritual of building or navigating a relationship. The Jordanian participant saw this immediately. The others looked surprised. (I must confess I didn’t understand this, too, until a Kurdish-Iranian friend had explained this dynamic to me). The cross-cultural implications are clear. If I judge your actions by unknowingly mis-inferring your intentions (being influenced subconsciously by my own cultural assumptions), all kinds of misunderstandings and tensions can arise. It cautions me-us to approach people and groups from different cultures with an open mind, a spirit of curiosity and a great deal of humility. Bottom line: We’re not only negotiating a price; we’re also negotiating a relationship.

18 Comments

‘The currency of real networking is not greed, but generosity.’ (Keith Ferrazzi) One of the skills in Action Learning is to distinguish between a presenter who is wrestling with a question from one who has become completely stuck. In the former case, it’s often most useful simply to sit with the presenter in silence while the question does its work. In the latter, the facilitator may offer the presenter an option of ‘peer-consultancy’, if it might help break the mental deadlock. In order to do this well, however, and to ensure that ownership and agency remain with the presenter, the facilitator can follow a specific sequence of interventions and process steps:

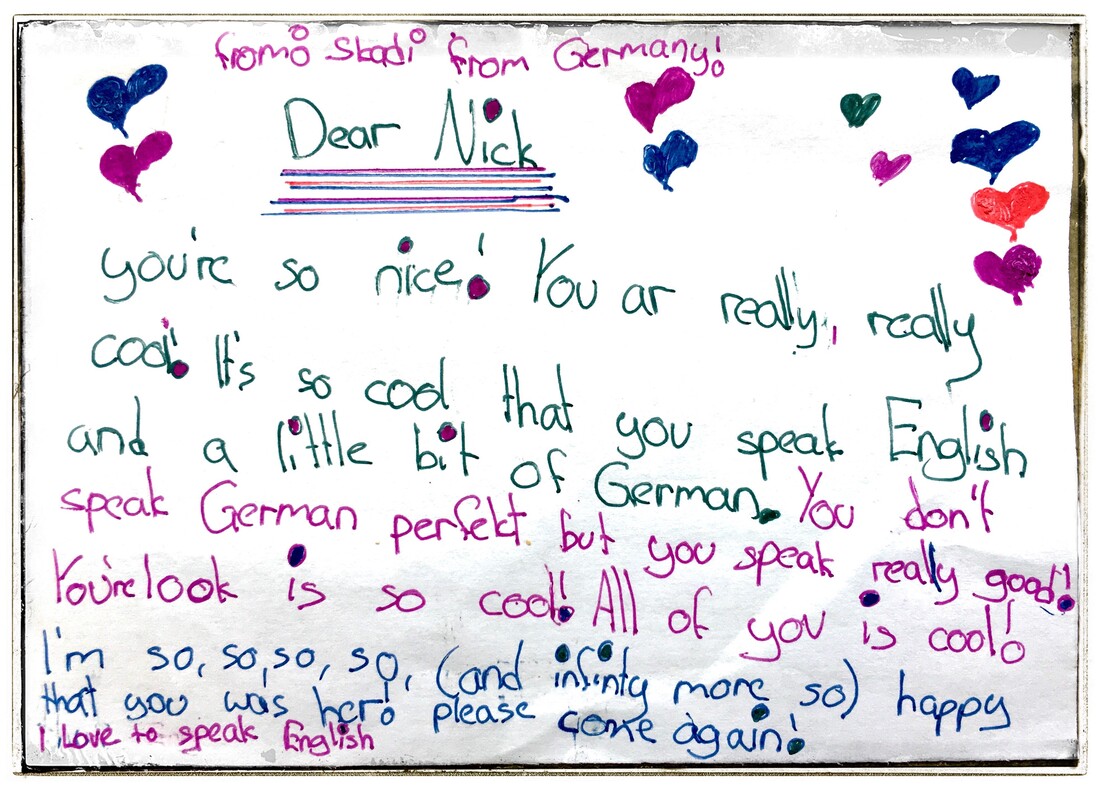

A few words of caution. First, beware of introducing the peer-consultancy approach without checking in with the presenter first. If the presenter is deep in thought, such a shift in approach may feel premature of patronising, as if inferring that they’re unable to work out a solution for themselves. Second, beware of any formal or informal (e.g. age, gender, race) hierarchical dynamics in a group. Presenters may feel that they ought to respond to all insights out of respect for those who shared them, or obliged to agree with ideas proposed by someone they regard as an authority figure. 'There is no act too small, no act too bold. The history of social change is the history of millions of actions, small and large, coming together at critical points to create a power that governments cannot suppress.' (Howard Zinn) At the heart of coaching generally lays a desire and opportunity for impact and change, a goal that may seem obvious, but one that raises important questions. As coaches aspiring to make a difference in the world, we can find ourselves navigating complex dilemmas. When we work with agents of change in, say, NGOs, charities, churches or public sector organizations, we often seek to empower individuals, teams, and organizations to be resourceful and effective in achieving transformation. One challenge we may encounter is determining the coaching agenda. A Western coaching ethic advocates for giving the client complete control over the agenda, focusing on their chosen goals and boundaries. While this approach seems straightforward, our intention of promoting social change may lead us to contemplate how much influence we should exert on the client’s journey. What if the client's solutions seem unethical, ineffective, or could pose risks to broader social development? Furthermore, when working in diverse cultural contexts, we need to be mindful of differing perspectives on individual autonomy. In some Eastern and Southern cultures, the concept of setting individual goals might not resonate the same way it does in the West. People in these cultures often prioritize the wishes and expectations of a wider group, whether family, team or community, before their own hopes and ambitions. We could risk inadvertently imposing our own cultural values onto the client. The solution often lays in recognizing the significance of context and building a strong and trusting relationship with the client. By understanding the dynamics of power, language and agendas that may emerge between us, we can gain insight into the issues at hand and potential solutions. We become allies, working together to achieve meaningful impact. A critically-reflective process allows us to adapt our coaching practice on route and to challenge our assumptions as we learn and grow. ‘One fish asks another fish ‘How is the water?’ The two swim on for a bit and eventually the other fish replies, ‘What is water?’’ (David Foster Wallace) The more I know, the less I understand. That’s the conclusion I came to after spending 5 years in a Christian faith community in London with 70% Nigerian people, 20% Ghanaian, 8% Mauritian and 2% from the UK. It’s a belief that’s been reinforced by 7 years closely alongside people from the Philippines and other countries in East and South East Asia. Beyond surface-level cultural traits such as distinctive clothing and food, culture runs very deep, mostly well below the radar of conscious awareness. Like the values and beliefs that underpin it, culture often only becomes known, including to ourselves, when we encounter a person or situation that contradicts or clashes with it. It can take us by surprise. I’ve made various cross-cultural blunders on route, ranging from an innocent hug in one context to posing questions in a group in another. On reflection, I’ve sometimes been astounded by my own naivety. Yet few opportunities for learning compare with a cross-cultural experience. It may feel like a bumpy ride on route yet the results can be transformational. [See also: Cross-cultural coaching; Crossing cultures; Cross-cultural action learning] ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. In my first encounters with the Philippines, I was surprised by how often people asked me about my meals. ‘Have you eaten?’ This included during conversations online. I learned, over time, that the question arises out of an economic context in which food is often scarce owing to high levels of poverty, and a cultural context in which the health and well-being of one’s neighbour is considered important. It means the question is literal and it calls for a literal response. If I answer ‘no’ while I’m there physically, I’m likely to be offered and given a meal; even if the person who’s asking is poor. Rudo Kwaramba, a Zimbabwean colleague, explained a similar dynamic whilst working together on an assignment in Uganda. I had been invited there to help an NGO address a key challenge: that managers in rural community-based projects were, apparently, bad at addressing poor performance. Rudo reflected: ‘In wealthy countries, if you can’t earn an income or lose your job, your government provides you with financial support; if you become injured or unwell, your health system or insurance covers you. In poorer countries, people can only look to each other for support.’ It means that, in such contexts, to establish and maintain positive relationships with one’s extended family and neighbours is essential for survival. It also means that to support the health and wellbeing of one’s neighbours is critical too. There is a sense of radical interdependence, a pragmatic-ethical need, that drives cultural behaviour. Against that backdrop, we discovered that managers who were living and working in the same communities as their staff felt unwilling and unable to address poor performance – in case it damaged the network of relationships. It was the core issue for them. This insight moved the culture-shift question in the work from a simplistic-transactional, ‘How to change the performance management system’, to a deeper-relational, ‘How can we hold honest conversations that don’t harm community?’. It proved transformational. As I focus back on South East Asia, I notice that as some countries have grown in wealth, they have experienced a corresponding shift towards individual-orientated cultures. It's as if: the richer I am, the less I need you. ‘Have you eaten?’ is often retained, yet as a simple greeting, not as a literal inquiry or as an invitation to a meal. So, I’m curious: what have been your experiences of working cross-culturally? What have you learned? How far can action learning (a form of small-group peer coaching) be useful in fast-paced and complex humanitarian contexts, in countries as diverse as Bangladesh, DRC, Iraq, Jordan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Somalia and Syria? What would it take to make coaching and action learning effective in these different cultural environments? These were questions I was invited to explore and test with ALNAP and ALA’s Ruth Cook during the past 18 months.

The idea was to train field-based practitioners in action learning techniques, then to mentor them as they adapted and applied them in disaster zones. Our goal was to learn from this experience too. Travel restrictions meant that workshops were all conducted online, which created its own challenges vis a vis patchy internet connectivity and access to training resources via cell phones, yet we-they persevered and the experience proved fruitful. I was particularly interested in cross-cultural dimensions and dynamics in these training groups. Workers in humanitarian crises face intense time pressures and it could have been tempting to short-cut personal introductions and press ahead with the task. In some cultures, investing in relationship and trust-building is integral to the task and, therefore, inseparable from it. We chose, therefore, to create opportunities, where possible, for participants to get to know and understand us and each other from the outset. In Western models of action learning, emphasis is often placed on posing coaching-type questions that are short, sharp and direct. If, however, we don't pay attention to relevant cultural norms including relational preamble (e.g. ‘I am pleased to be here. Thank you for the opportunity to ask this question…’) such questions can be experienced as blunt, harsh or rude. It's important, therefore, to allow for different cultural framings and expressions. We were aware that, in contexts such as the UK and USA, action learning tends to assume an egalitarian culture within a group, within which participants are and feel free to invite and pose challenging questions to one-another. In some cultures, however, where perceived authority and social status are based on e.g. age, gender or tribe as much as on formal hierarchy, careful composition of and contracting in groups are critical success factors. In some cultures, to pose a question directly to an authority figure could be perceived as insubordinate, disrespectful or even insolent. Authority figures may be expected by others always to have the ‘right’ answers and to pose a question in a group risks shaming that person, a loss of face, if they are unable to answer it. One way to avoid this issue is to invite participants to write down questions and hand them to the person first, who can then chose which to respond to. In some cultures, it would feel inappropriate for a participant to decide unilaterally on an action at the end of an action learning cycle without having first run the idea past their line-manager for approval. This may partly be indicative of where decision-making authority is held in that hierarchy. It can also signal deference to or respect for an authority figure. One way to address this would be for a participant to relate back to the group at a subsequent meeting on what actions have been agreed. When using a peer-consultancy version of action learning, in which participants are invited to offer suggestions for consideration as well as questions, particular challenges can arise. In some cultures, participants may feel compelled to accept the first suggestion that is offered, or to agree to whatever is suggested by a perceived authority figure. Again, writing down questions to offer a presenter can help to address this. When using an appreciative version of action learning, in which participants help a person to identify what personal and contextual factors contributed to the success of an initiative, there can be challenges too. In some cultures, it can turn into a praise-party, with participants wanting to affirm the presenter rather than to tease out success factors. One way to address this is to allow space for praise first, then to move onto the more structured process. In other cultures, a presenter may feel uncomfortable to comment on what they did well personally in case it sounds immodest. Two possible ways to address this are to invite the presenter to comment on what other people may have noticed about his or her contribution, thereby attributing the qualities to a third-party perspective rather than their own, or to depersonalise it as ‘This happened’ rather than ‘I did this.’ I am deeply indebted to all of the participants in this initiative who contributed so richly to our learning and ideas. What have been your experiences of coaching, training or action learning in different cultural environments? What have you learned - and what would you recommend to others? (See also Nick's: Cross-Cultural Action Learning webinar, December 2021) 'The good news is you have 200 people working for you. The bad news is they don't see it that way.' (Euan Semple) I love how humour can transform, creating fresh perspective by shedding novel light on people, issues and situations in ways that plain comment or description just can’t. It can be a great technique for reframing, making the familiar unfamiliar and vice versa too. I worked with a colleague, Benjamin, who enjoyed using phases playfully. If something went wrong or didn’t work out as we had hoped, or if someone was sounding unduly pessimistic, he would simply grin disarmingly and say something like, ‘Ah well, every silver lining has a cloud.’ Humour can inject energy, diffuse tension, bring people together, make life and work more fun. Smiles and laughter are good for health and well-being too. I worked with Richard, an occupational psychologist and HR leader who had a passion for developing talent and enhancing people’s commitment, capacity and contribution. He could have presented his case for change using formal statistics, spreadsheets and information. Instead he would start with an open, provocative smile, ‘There are people who left this organisation years ago...but still turn up for work every day.’ It had a very different qualitative feel to sarcasm, cynicism or bland statement of fact. It was a powerful use of irony to highlight an issue, evoke curiosity, challenge the status quo and invite a response. I could almost hear every person in the room thinking, ‘I wonder if that could be me?’ For humour to work, it needs to have some resonance with what the audience already knows, perceives and experiences as real and true. I think back to the first time I read Scott Adams’ The Dilbert Principle (1996). I sat on my bed and literally cried laughing. It was for me, as for many others, a refreshingly new approach to shining a critical spotlight on the quirky, crazy and self-defeating politics of office life. This, however, signals that humour is culturally and contextually-relative. Have a glance, for instance, at satirical Despair.com. Are its posters funniest for those who have seen their earnest equivalents first? What have been your best experiences of humour at work? Who or what made them so effective? How can I help you create a more inspiring and effective workplace? Get in touch! [email protected] ‘Britons’ top three favourite accents are Irish, Welsh and Geordie. The least favourite are Brummie, Scouse and Cockney. People with a Yorkshire and Welsh twang sound the happiest followed by Scouse. The Southeast sound the most intelligent and Glaswegians sound the angriest.’ (Howarth, Dec 2017) Isn’t it interesting that accents carry such connotations and evoke such feelings? I arrived some years ago at London School of Theology in the South of England as a new student. It was a daunting experience: that first-day-at-school feeling. At the first evening meal, I heard another student speak with a Northern accent and instantly connected with him. We became great friends. It was as if our common accent gave us a deep point of contact – a ‘secure base’ (Bowlby) in an alien environment. Accents, like other cultural distinctives, create and sustain a sense of unique identity and belonging. They distinguish 'us' from 'them', creating a socio-psychological boundary, an existential and emotional safety barrier, a metaphorical extended family, in the midst of a larger and potentially overwhelming complexity. I remember moving to a new area to engage in community development work. I had to learn the local accent convincingly in order to be accepted by local people. Accent influenced trust. Accents can serve as a useful metaphor for cultural issues in organisations too. Here are some useful questions for leaders, OD practitioners and coaches: What functions as a secure base for people in this team/organisation? What brings hope and fulfilment here - or provokes anxiety or resistance if threatened? Where, when and how have helpful boundaries in this organisation become unhelpful barriers? Where may I need to learn a new ‘accent’ in order to build credibility and relationship? Coaching has become increasingly well-defined over recent years, particularly owing to great efforts by e.g. the International Coach Federation and European Mentoring & Coaching Council to clarify, advocate and promote core professional standards and ethics. I believe that, on the whole, this has been a useful development. It adds credibility to the field and, in principle, focus, parameters and accountability for those who study, train and practice within it.

There are challenges too, not least the process and cost of credentialing to be recognised by the professional bodies. This can be prohibitive for practitioners who don’t have access to the time or financial resources to do this in spite of having, potentially, extensive knowledge, skill and experience in the coaching arena. The risk here is that increasing professionalism leads to increasing exclusivity, dictated more by economic circumstances than passion or expertise. There are wider and deeper questions. Coaching is without doubt a powerful field of research and practice that can make a very significant impact. Its focus on reaching goals and solutions can enable people to live and work with greater focus, better ideas and higher levels of commitment. I have felt and witnessed it so many times that I am beyond need for convincing. Yet, as I read and speak with fellow coaches, it often feels like something important is missing. How far are our coaching assumptions, models and approaches (e.g. vis a vis personal efficacy and choice) appropriate to non-Western cultures - yet applied uncritically? How well do we enable clients to grow in insight and resourcefulness as reflective practitioners – beyond reaching goals or solving issues? How willing are we to raise and challenge systemic implications of client choices – e.g. for families, teams, organisations and wider cultural groups? Am I alone? What do you think? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed