|

‘Learning is a treasure that will follow its owner everywhere.’ (Chinese proverb) Action Learning facilitator training with different participant groups always surfaces fresh and fascinating insights, emphases and challenges. This week’s ALA training programme was with a group of health professionals in diverse roles and fields of practice ranging from nursing, occupational therapy and podiatry to mental health, speech and language and education. I was inspired by their enthusiasm, personal ethics and genuine commitment to culture change. As we worked through Action Learning principles and techniques and how to enable groups to do it well, we explored 5 shift areas to facilitate a transition: from diagnosis to elicitation; from issue to person; from there-and-then to here-and-now; from first questions to follow-up questions; from reflection to agency. I’ll say a little about each of these dimensions with some practical examples below. The goal in each is to enhance participants’ learning and impact. From diagnosis to elicitation is a shift in who owns the issue from, say, ‘Tell me more about X so I can help you?’ to e.g. ‘What questions is X raising for you?’ From issue to person is a shift in focus from, say, ‘What’s the situation?’ to e.g. ‘What challenge is this situation posing for you?’ From there-and-then to here-and-now is a shift in temporal orientation from, say, ‘What have you tried?’ to e.g. ‘Given what you have tried, what stands out as the critical issue now?’ From first questions to follow-up questions is a shift in depth to move below and beyond, say, ‘How important is this to you?’ to e.g. ‘Given how important this is to you, what are you willing to risk?’ From reflection to agency represents a shift in traction from, say, ‘What sense are you making of this?’ to e.g. ‘What actions will you take to address this?’ A skill of the facilitator is to build the capacity of an Action Learning set to navigate these shifts in service of a presenter.

8 Comments

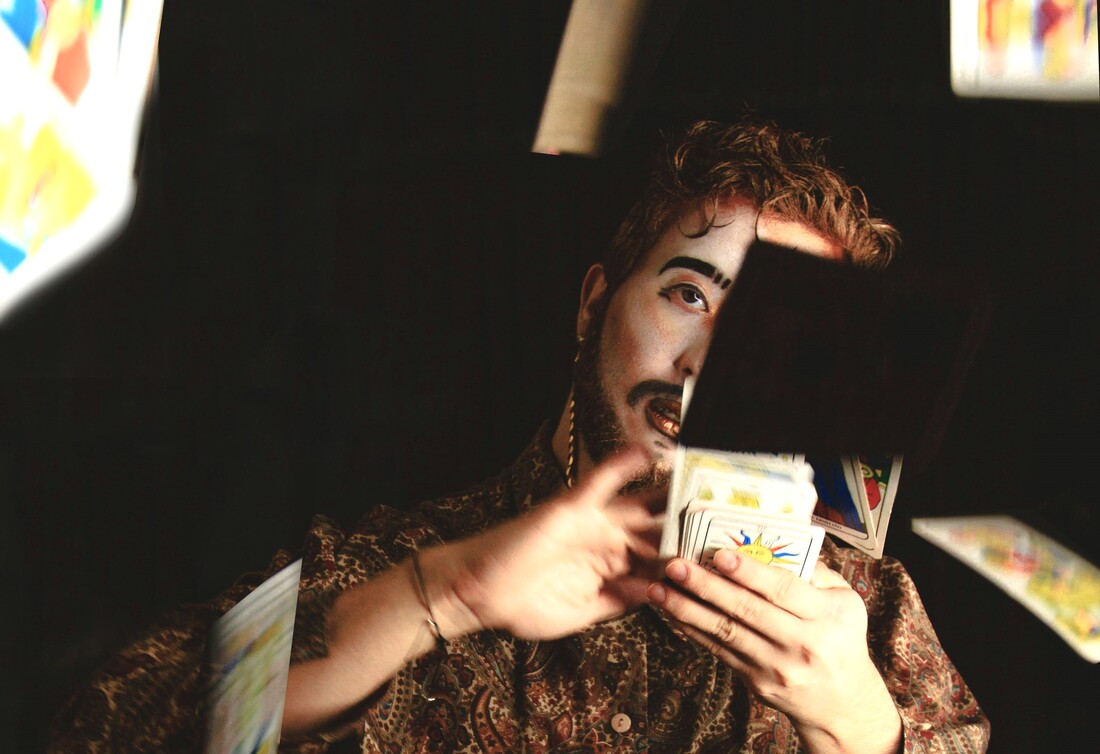

‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers) ‘The currency of real networking is not greed, but generosity.’ (Keith Ferrazzi) One of the skills in Action Learning is to distinguish between a presenter who is wrestling with a question from one who has become completely stuck. In the former case, it’s often most useful simply to sit with the presenter in silence while the question does its work. In the latter, the facilitator may offer the presenter an option of ‘peer-consultancy’, if it might help break the mental deadlock. In order to do this well, however, and to ensure that ownership and agency remain with the presenter, the facilitator can follow a specific sequence of interventions and process steps:

A few words of caution. First, beware of introducing the peer-consultancy approach without checking in with the presenter first. If the presenter is deep in thought, such a shift in approach may feel premature of patronising, as if inferring that they’re unable to work out a solution for themselves. Second, beware of any formal or informal (e.g. age, gender, race) hierarchical dynamics in a group. Presenters may feel that they ought to respond to all insights out of respect for those who shared them, or obliged to agree with ideas proposed by someone they regard as an authority figure. ‘The question is to provoke fresh thought, not to elicit an answer.’ (Stephen Guy) I thought that was a great way of framing it. At an Action Learning Facilitators’ Training event with the NHS this week, we were looking at open coaching-type questions in the exploration phase of an Action Learning round and how they differ from, say, simple questions for clarification. A great question for exploration often stops a presenter in their thinking tracks. We may notice them fall silent; gaze upwards as if on search mode; get stuck for words; speak tentatively or more…slowly. That’s very different to a presenter who answers quickly, fluently or easily – as if telling us something they already know or have already thought through for themselves. In a different Action Learning set recently, one presenter did just that. They were speaking as an expert, not as a learner, so I invited them to count to 10 silently before responding to any question posed – and invited the rest of the group to count to 10 silently too, after the presenter had spoken, before offering a next question. The idea here was to allow the questions to sink deep. Thomas Aquinas, a philosopher and theologian, commented (my paraphrase) that a great question sets us off on a journey of discovery. Brian Watts observed, similarly, that the word question itself has the word quest embedded in it. Sonja Antell invites a presenter simply – but not always easily – to ‘sit with the question’, to reflect in silence and allow the question to do its work. It’s often the place where transformation occurs. ‘Open-ended questions can help clients reflect and generate knowledge of which they may have previously been unaware.’ (Jeremy Sutton) You may have noticed when you order or buy something that, before asking you for payment, the salesperson may ask, ‘Anything else?’ It’s a simple prompt that, when posed, may cause you to remember something, or to make a choice vis a vis something over which you had been wavering. This same approach can be useful in coaching. A coach could ask during the contracting stage: ‘Is there anything else we should be talking about?’ It can sometimes reveal a very significant issue that, until invited, feels unclear to the client, lays out of conscious awareness or has not yet been aired. In action learning, similarly when a facilitator invites a presenter to say something more about the issue they would like to think through, insights that come to mind or actions they plan to take, they can ask, ‘Anything else?’ A presenter, when prompted, will often respond with: ‘Oh yes, and…X’ So, now for a brief moment of reflection. What ideas come to mind for you now as you read this blog? Jot down those that surface immediately… then pause for a moment before moving on to something else in your busy schedule. Ask yourself: ‘Anything else?’ and see what may emerge. ‘Behind every problem, there is a question trying to ask itself. Behind every question, there is an answer trying to reveal itself.’ (Michael Beckwith) Second-guessing. It creates all sorts of risks. ‘What time does Paul’s meeting finish?’ Is that a simple request for information, or is there a question behind the question? ‘I’d like to meet with Paul this afternoon. What time will he be free?’ That’s better. ‘I need you to present an urgent strategy update to the Board.’ Again, is that a simple instruction, or is there an issue that lays behind it? ‘I’d like to demonstrate to the Board next week that our investments are achieving the desired results.’ Better. A problem with a question that fails to reveal the question, the issue, that lays behind the question is that it leaves the other party to fill in the gaps. In doing so, they are likely to draw on their own assumptions – which could be very different to your own – or sometimes their anxieties. ‘Is he complaining that Paul’s meeting is over-running?’ ‘Is she inferring there’s a problem with my work on strategy delivery that I hadn’t been aware of?’ Simply stating our intention can make all the difference. ‘Wait time is making space for authentic learning.’ (Takayoshi & Van Ittersum) A key skill in Action Learning is an ability to wait. It calls for patience and a positive tolerance of periods of silence. Imagine the presenter who receives questions from peers yet answers them too quickly or too easily, without allowing the questions enough time to sink deep. Such responses can sound and feel like surface-level learning, where a presenter knows, or is reasonably easily able to work out, a solution without much need for consideration. A metaphor that comes to mind is that of the UK innovator, Barnes Wallis who, during World War 2, designed a revolutionary bomb to break through dams. ‘The bomb would spin backwards across the surface of the water before reaching the dam. The spin would then drive the bomb down the wall of the dam before exploding at its base.’ It took time and patience from the moment it was released until the cracks began to show, but then… breakthrough. This principle of allowing time for questions to sink deep often proves critical to a presenter faced with complex problems in achieving their own breakthroughs: those profound moments of insight and agency that transform everything. It calls for discipline from peers, to wait and hold silence for the presenter before posing a next question. For people who find silence difficult, this entails learning to sit comfortably with discomfort. It’s well worth the wait. 'The art of proposing a question must be held of higher value than solving it.' (Georg Cantor) I spent the past couple of weeks working with the public sector in the UK, providing Action Learning facilitator training for a team of managers and professional mentors. The purpose of the initiative is to equip the mentors to offer Action Learning sets to registered managers of care homes. Action Learning will enable those managers to navigate complex challenges they face, whilst building on the existing skills portfolio of the mentoring team itself. One of the challenges for mentors can be to make a shift from offering information or advice to mentees, which is often core to a mentoring role, to offering open questions in an Action Learning style instead. One participant, Mark, offered a useful insight to peers in his training group, to help make this psychological and practical transition from guidance to questions: ‘If I think of a solution and frame it as a question, it’s likely to come across as a suggestion.’ I found this very interesting because it signals the implicit, subconscious influence that our thinking, as facilitators or peers, can have on what we do and on the impact it can have. This could include, for instance: our beliefs about our role; how we believe we could add value to resolving an issue; what we believe a presenter could or should do etc. – even if we don’t say it out loud. This calls us to prepare ourselves mindfully before we step into a round. 'I would rather have questions that can't be answered than answers that can't be questioned.' (Richard Feynman) When a person introduces an issue they are facing, we and often they are not always clear at the outset what underlying challenge that issue is posing for them. Rather than asking more questions about the issue itself, however, we could invite the person to reframe the issue as a question. ‘What questions come to mind as you think about this?’ ‘What question is this raising for you now?’ I worked with a strategy consultant who asked great questions; for example ‘What are the questions that, if we were to answer them, would enable us to make strategic decisions?’ In Action Learning sets, we could ask a presenter, for instance, ‘What are the questions you’d find most useful for us to ask?’ And, in high-challenge coaching, ‘What’s the question you’re hoping I won’t ask you?’ Priest-philosopher Thomas Aquinas observed that a good question can set a person off on a quest; a restless and intense journey of searching and discovery. It’s very different to providing a superficial answer that can close thinking down. I sometimes go one step further and ask, ‘What’s the question behind the question?’ It can raise tacit, subconscious and intuitive knowing into view. ‘The smart ones ask when they don’t know. And, sometimes, when they do.’ (Malcolm Forbes) We sometimes discover in new Action Learning sets that participants are unsure about the distinction between questions for clarification and questions for exploration. Participants may wonder, similarly, if and when closed and open questions should be used. This can lead to all kinds of awkward mental and linguistic gymnastics such as, for instance, wanting to ask a simple question for information, yet trying hard to frame it as an open question. I find that one useful way to mark the difference between clarification and exploration questions is to consider, ‘Who is the answer to the question for?’ If I ask a question for clarification, the answer is for me, so that I will know or understand something better. If I ask a question for exploration, it’s offered as a gift that may, I hope, enable another person to gain insight and know or understand something more deeply or broadly for themselves. We also sometimes discover that participants get a bit stuck when thinking about how to transition from questions for exploration to questions for action. They may wonder if, for instance, questions for action are questions for exploration that focus on action. I find a useful way to mark this shift is to think of questions for exploration as divergent (opening out) and questions for action as convergent (drawing together, to enable a close). What we see here is that what makes a good question in Action Learning is determined less by rules about the structure of a question itself (e.g. whether it is an open or a closed question), and more by the focus and orientation of questions at each stage of the process. Participants pose questions in service of the presenter and, at the end of the day, it’s for the presenter to decide which land usefully for them or enable a shift towards a solution. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed