|

‘You can never really know someone completely. That’s why it’s the most terrifying thing in the world, really – taking someone on faith, hoping they’ll take you on faith too. It’s such a precarious balance. It’s a wonder we do it at all.’ (Libba Bray) There’s an idea in Gestalt psychology that we’re predisposed, hard-wired, to ‘fill in the gaps’. Here’s a real and practical example. I was once invited to facilitate a conference of around 50 people from diverse professional backgrounds in the housing sector. I had never met anyone in the group and they had never met me. I stood up on the podium, introduced myself simply as ‘Nick Wright, an organisation development consultant from England’, then invited everyone to take a pen and paper. I explained that I would ask them a series of questions about myself, to which they were to guess the answers. ‘Which newspaper do I read?’ ‘What political party will I vote for at the next General Election?’ ‘Am I married, or single?’ ‘What is my professional background?’ ‘What’s my favourite hobby outside of work?’ I then asked who had been able to answer every question. Everyone raised their hands. I now invited them to draw a simple face against each of their answers – which they wouldn’t be expected to share in the group. A happy face meant their answer drew them towards me; an unhappy face that it pushed me away. A neutral face meant, well, neutral. Again, everyone managed to do it. I paused and invited them to reflect at their tables on what had just happened. Person after person said how astonished they felt at how quickly and easily they had created a profile of me in their minds, and how that had influenced how they felt about – and were now likely to respond and relate to – me. They had filled in the gaps of not-knowing by drawing on hopes and fears, past experiences, personal projections, cultural assumptions etc. Filling in the gaps enables us to relate quickly to others rather than starting every relationship as if from scratch. It also risks unhelpful stereotyping and bias. This raised important questions for participants at the conference so I offered 3 principles: compassion, curiosity and challenge. Compassion: ‘What do I need to feel safe to contribute in this group? ‘How can I demonstrate a compassionate stance towards others?’ Curiosity: ‘What assumptions am I making about those around me, e.g. based on their looks, accent or job title?’ ‘Who or what is influencing the ways in which I’m thinking about, feeling about and responding to others?’ Challenge: ‘What am I not-noticing about those around me?’ ‘How open am I to have my beliefs about others tested?’

12 Comments

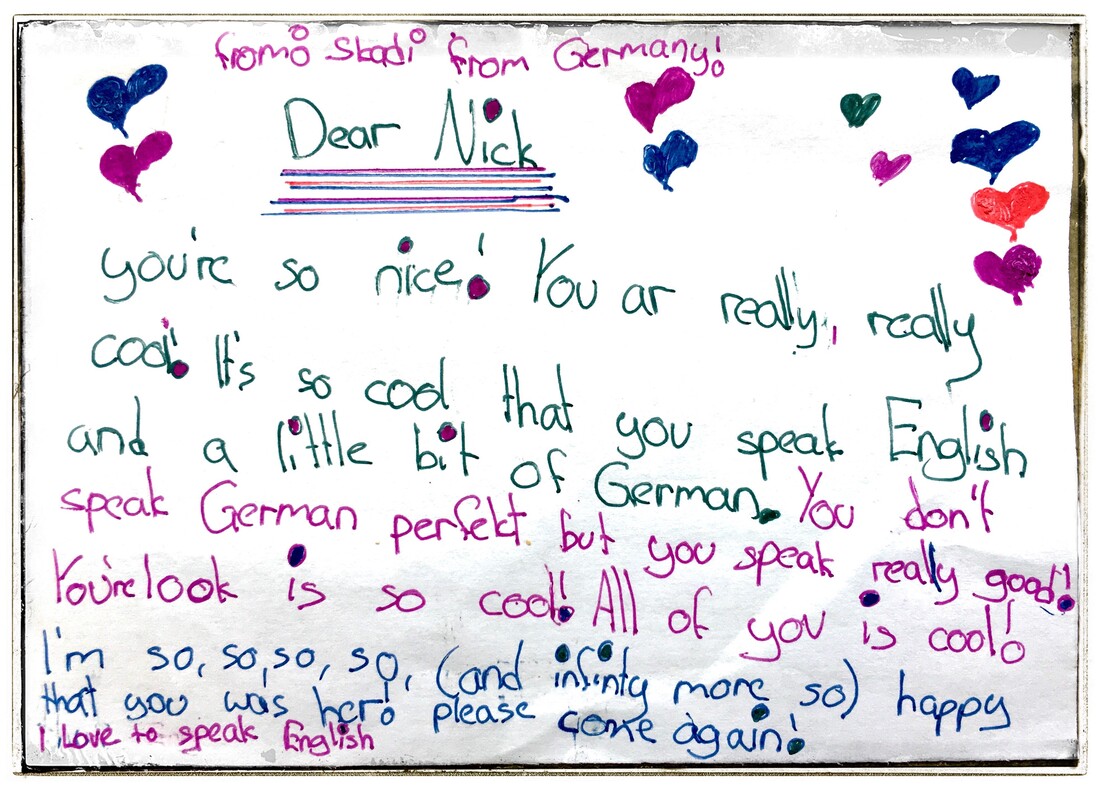

‘No matter what happens, we always have a choice.’ (Napz Cherub Pellazo) ‘What are your options?’ is a good question in coaching, except when it isn’t. Many people come for coaching in the first place because they face an issue or a dilemma, and they can’t see a way forward. Sabine Dembkowski and Fiona Eldridge observed this phenomenon in their article, ‘Beyond GROW’ (2023): ‘Clients often experience a stuck state…where they feel trapped as if there are no alternatives or keep circling around the same issue without being able to generate new options.’ Against this backdrop, ‘What are your options?’ can be met with a bemused, ‘I don’t know. That’s why I’m here.’ An inexperienced coach may feel stuck too at this point and perhaps, hoping to find a way through, ask something along the lines of ‘What have you already tried?’ Again, this may elicit little more than feedback on what the client has already done and found to be ineffective (which the client knows already anyway), and bring both parties back to square one. An alternative, and potentially more useful, framing could be something like, ‘Given what you have tried already, what is the crux of the issue for you now?’ This may stimulate fresh insight and, in turn, raise new possibilities into awareness. A different approach can be to pose questions that aim to stretch the boundaries of the client’s current constructs and imagination, for example: ‘What would you do if you had a blank cheque?’ ‘What would you do if you felt no fear?’ ‘What could you do if you were not answerable to anyone?’ Claire Pedrick might invite a stuck client to generate a spectrum of options, from ‘Do nothing’ to whatever they would regard as a ‘Nuclear option’. Ian Gray deploys a fun and radical brainstorming technique, where every third option or idea must be ‘illegal, immoral or absolutely unworkable’. If a client still feels completely stuck, I may invite them to take a large, blank sheet of paper, draw themselves at the centre, then co-create radical options in the form of a mind map. In order to help minimise the risks of instinctive psychological and emotional resistance or push back from the client, I emphasise that the options simply represent possibilities, not what the client may want or consider right to do. Against each option, I then invite the client to respond to two questions: ‘If you were to do this, what would it make possible (or right)?’ and, ‘If you were to be do this, what would you need?' [See also: Out of the building; Worst possible idea] ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. ‘What is it your plan to do with your one wild and precious life?’ (Mary Oliver) Íñigo López de Loyola suggests a fast-forward in your imagination to the end of your life, then to ask yourself seriously from that standpoint what you will want your life story to have been. Having decided it, rewind back to the present and ensure that your vision of the future guides your priorities, decisions and actions now. This idea resonates with Stephen Covey’s 'begin with the end in mind', and Simon Sinek’s 'start with why'. According to John Kotter, if our vision is convincing enough to the mind and compelling enough to the heart, we are most likely to see it through. Without such a vision, we may drift meaninglessly. I believe the best visions are rooted deeply in ethics and values and, in essence, a fulfilment of them. I have been incredibly inspired by Jasmin’s vision, a poor follower of Jesus who lives among the poor in the Philippines: ‘Whatever status or power you have, use it for those who are vulnerable; whatever money you have, use it for the poor; whatever strength you have, use it for the weak; whatever hope you have, use it to bring hope to those who live without hope. Speak up for justice and truth – whatever the cost. Pray.’ The challenge is not just in the aspiration itself but in her sheer determination to live it out in practice. She scares me. My own vision is shaped by a trust in God too. I slip and slide on route and have sustained and caused too many scars to prove it, yet Jesus still influences profoundly the purpose, focus, boundaries and possibilities of my life and my work. As I get older, I'm experiencing a subtle and gradual shift from what I want to do in the future, to what legacy I want to leave behind me. It doesn’t feel like a mid-life crisis. Echoing Richard Rohr, it feels more like a falling upward than a falling apart. I still want to make a significant, positive and tangible difference in the lives of the poor and most vulnerable people in the world. I – you – we can be hope. What’s your vision for 2022 and beyond? How will it influence your decisions now? ‘I have a dream.’ (Martin Luther King) We were leading a strategy development process at an international NGO and wanted to envision ourselves and each other rather than to paint bleak pictures of burning platforms, a future to avoid or a present to escape. This was instead about inspiring wonder, hope and aspiration. ‘Imagine if…’ We invited people to paint, depict and enact future scenarios – the futures that our beneficiaries, supporters and we ourselves dreamed of. It was about imagining, hoping, reaching, aiming high. There are parallels with the ‘dream phase’ of Appreciative Inquiry. This is where we invite people to imagine a different, brighter future: what they would like things (e.g. relationships, ways of working, success stories) to be more like, more of the time. There are also parallels with posing a ‘miracle question’ in solutions-focused coaching or therapy. This is where we invite a person to imagine vividly that a desired future state has already been reached or achieved. To experience it as if it really is. This is important and here are some reasons why. If we focus our attention only on problems, deficits or undesirable states, it can evoke anxiety, drain energy and close-down creative thinking. I say ‘only’ because there are some situations (e.g. aspects of accountancy/IT/audit) where identifying problems/errors and fixing them can be very important. Some people also get a buzz, a real sense of achievement, from searching for, sniffing out or hunting down problems and sorting them out. If, however, we focus entirely on problems, red-ratings or what is missing or broken, psychologically and culturally-speaking there is a risk that they grow out of proportion, that we become unhelpfully fixated on them and that we lose a broader perspective – thereby undermining vision, awareness and morale. If, conversely, we invite people to dream and tap into the power of positive imagination, it can inspire fresh hope, open new horizons, release creative energy and surface great ideas. So – when was the last time you spent time dreaming..? ‘Organisations do not exist. People do.’ This was the provocative title I chose for a dissertation I wrote some years ago now. The idea, the belief, has stayed with me. It shapes how I think about and approach leadership development, OD, coaching, facilitation and training. Inspired by Gareth Morgan’s Images of Organisation and insights from social constructionism, I continue to be fascinated by how the images we hold when we think of ‘organisation’ influence and, at times, constrain our awareness, actions and the range of options we believe we have available to us.

So I meet you in the street and ask you to tell me about you organisation. You may start by telling me about the products or services you provide. You may well move onto saying something about the structure, by which you are less likely normally to mean the physical structure and more likely to mean how jobs, roles, responsibilities and authority are organised. You may well describe or depict the structure like an organisation chart. Now here’s the important bit. Insofar as you and everyone else in the organisation believe this structure exists and behave as if it does, to you – it does. Now imagine that the structure dissolves so that what is left is people and whatever physical assets the organisation may own. Imagine that people are released from job titles, role boundaries and that you now see them as whole people, rich with experiences, in vibrant colour. You have a task to achieve and you invite people with the best energy, enthusiasm, skills and life experiences to offer. As different tasks arise, different people get involved. Imagine, just for a moment, what that could look and feel like and achieve. Imagine the creativity and potential for innovation. Imagine! What did this thought experiment reveal for you? What images are constraining you or your clients? What assumptions are you making about what’s possible? What dreams could be realised if the images were to change? What would it take to make the shift? Take an issue (e.g. a painful memory, a foreboding experience) and hold it in your imagination for a moment. Now freeze the movie in your mind into a still shot. Tune down the colour until it’s black and white. Shrink the picture until it’s the size of a postage stamp. Cast the image away from you, as if into a distant bin. Now return to the present moment, the here-and-now. Notice the difference in how you are feeling. Allow the feeling to dissipate. Breathe.

Now, by contrast, imagine a positive experience, a great outcome, an exciting future. Hold the image in your mind. Tune up the colour until it’s vivid, radiant and bright. Turn up the sound until you can hear everything in crystal clarity. Really feel the positive energy and hope. Now turn the image into your favourite colour – a colour you associate with feeling happy, excited, relaxed. Hold the image, see the colour, feel the feeling. Now return to the here-and-now. Breathe. We hold memory and imagination as sensory experiences in the mind, body and emotions. Constructing, deconstructing and reconstructing experiences in this way through coaching or therapy can create profound shifts in what we notice, how we feel, how we behave and what we evoke. It can reduce pain from the past, present new solutions, engender fresh hope and enhance results. What’s your experience of using the imagination to influence change? A well-known management development agency invited me to take part in a masterclass in Appreciative Inquiry (AI) some years ago, at around the time when AI was first becoming popular in the UK. The idea was that I would write a review of the workshop afterwards that would be published in the agency's monthly journal. I have to confess that I wasn't exactly blown away by the experience. Phrases like 'Emperor's New Clothes' came to mind and I wrote a critical review accordingly. Needless to say, it wasn't published!

I have, however, used aspects of AI on numerous occasions since with different people and organisations and I have to say I've been impressed by the results. I like its emphasis on imagination, positivity and solutions. It fits well with my beliefs from social constructionism about how we create and co-create our own realities. Its discover, dream, design and destiny phases can envision and energise, inspire and motivate people far more than any problem-solving approaches I've seen or used. A simple question such as, 'What has inspired you in the last month?' really can transform the focus and energy in a team. The best article I've read on the foundations of AI and what it involves in practice is by Richard Seele (2008): An Introduction to Appreciative Inquiry. If you're interested in the AI and to learn more about it, Richard's article is well worth a glance. I have used, adapted and applied aspects of AI without ever having worked systematically through its 4-stage process. I'd be interested to hear from you if you have: what was the issue/opportunity you focused on, how did you approach it, what questions did you pose at each stage, what happened as a result? How would you describe your coaching style? What questions would you bring to a client situation?

In my experience, it depends on a whole range of factors including the client, the relationship, the situation and what beliefs and expertise I, as coach, may hold. It also depends on what frame of reference or approach I and the client believe could be most beneficial. Some coaches are committed to a specific theory, philosophy or approach. Others are more fluid or eclectic. Take, for instance, a leader in a Christian organisation struggling with issues in her team. The coach could help the leader explore and address the situation drawing on any number of perspectives or methods. Although not mutually exclusive, each has its own focus and emphasis. The content and boundaries will reflect what the client and coach believe may be significant: Appreciative/solutions-focused: e.g. ‘What would an ideal team look and feel like for you?’, ‘When has this team been at its best?’, ‘What made the greatest positive difference at the time?’, ‘What opportunity does this situation represent?’, ‘On a scale of 1-10, how well is this team meeting your and other team members’ expectations?’, ‘What would it take to move it up a notch?’ Psychodynamic/cognitive-behavioural: e.g. ‘What picture comes to mind when you imagine the team?’, ‘What might a detached observer notice about the team?’, ‘How does this struggle feel for you?’, ‘When have you felt like that in the past?’, ‘What do you do when you feel that way?’, ‘What could your own behaviour be evoking in the team?’, ‘What could you do differently?’ Gestalt/systemic: e.g. ‘What is holding your attention in this situation?’ ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What are you inferring from people’s behaviour in the team?’, ‘What underlying needs are team members trying to fulfil by behaving this way?’, ‘What is this team situation telling you about wider issues in the organization?’, ‘What resources could you draw on to support you?’ Spiritual/existential: e.g. ‘How is this situation affecting your sense of calling as a leader?’, ‘What has God taught you in the past that could help you deal with this situation?’, ‘What resonances do you see between your leadership struggle and that experienced by people in the Bible?’, ‘What ways of dealing with this would feel most congruent with your beliefs and values?’ An important principle I’ve learned is to explore options and to contract with the client. ‘These are some of the ways in which we could approach this issue. What might work best for you?’ This enables the client to retain appropriate choice and control whilst, at the same time, introduces possibilities, opportunities and potential new experiences that could prove transformational. Reaching 64 lengths felt like quite a stretch. I normally swim around 25 so pushing for a mile felt exciting yet daunting. When I did reach the final strokes, I felt tired yet exhilarated. It was a good feeling, a feeling of achieving something beyond my normal boundaries, routine, comfort zone. In that moment, I felt more alive somehow as if I had extended my boundaries into a new space. I was spurred on to test my limits by a good friend who takes his own sport, motorcycling, to extremes, perfecting his riding technique in every detail and crossing continents in ways I only dream of. Rho Sandberg added inspiration in her deeply thought-provoking blog, ‘Working with our Edges and No-Go Zones’: http://thegritintheoyster.cleconsulting.com.au/blog/working-our-edges-and-no-go-zones.

Rho, a coach and consultant, comments on how each time we reach the border of our experience, it’s as if we reach an edge. The edge represents an opportunity for growth and something new yet it can also sometimes feel unsettling, disorientating and anxiety-provoking. We may at times hesitate, avoid or pull back to avoid the discomfort or fear of what may lie beyond. ‘Will I be able to handle it?’ It could be a new relationship, a new job or taking something familiar to the next level. The edge can symbolise adventure...and risk. I remember that feeling vividly, the first time I set off to hitch hike around Europe. I had never done it before and felt butterflies of anxiety and thrill as I made preparations and finally stood at the road side, waiting for that first lift that would signal the start. Rho comments that, ‘An edge is the limit to what we know and are comfortable with’ and ‘a coach or consultant’s key contribution can be holding and supporting the client at the edge long enough for them to discover a little more about it’. This echoes with my own experience as coach, supporting people who face fresh opportunities and challenges in life or who are working through change and transition. It inspires me to continually develop my own thinking and practice too…how to keep growing, extending my own boundaries and not to stay within my safe circle of experience. My next challenge is to cycle 1,000 miles and I can already feel myself touching that edge. Rho’s advice: ‘The edge is an interesting place – I recommend taking a torch to find your way around.’ |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed