|

‘I have always felt that ultimately along the way of life an individual must stand up and be counted and be willing to face the consequences, whatever they are. If we are filled with fear, we cannot do it. And my great prayer is always that God will save me from the paralysis of crippling fear, because I think when a person lives with the fear of the consequences for their personal life, they can never do anything in terms of lifting the whole of humanity.’ (Martin Luther King) I know that fear. I have sometimes experienced it as a vague, background yet seemingly ever-present existential angst. At other times, it has been a response to a specific perceived threat, whether real or imagined, that triggers an anxious feeling. At such times I have learned…and I’m still learning…to pause, breathe, pray and try not to panic. Fight-flight-freeze is an instinctive rather than reflective response that can leave us feeling stressed, powerless and stranded. A real challenge is how to avoid feeding that fear. We may play out all kinds of catastrophic scenarios in the imagination, an endless list of what-if scenarios, amplifying our worst anxieties. We may avoid people, situations or relationships, a kind of flight response, to avoid the risk of our fears actually materialising. Our world may become smaller as we shrink back, self-protect, attempt to keep ourselves safe from harm. (And sometimes that’s a price worth paying.) In his astonishing autobiography, however, Martin Luther King recounts the way he found to face the dangers (which included relentless physical threats, bombing of his home and, ultimately, assassination) – inherent to his calling to address deep-rooted social injustice – and yet still to persevere. It was to face directly his fear of death before God and, by faith, to let go of that fear. That released him to be the remarkable and courageous role model we still admire today.

8 Comments

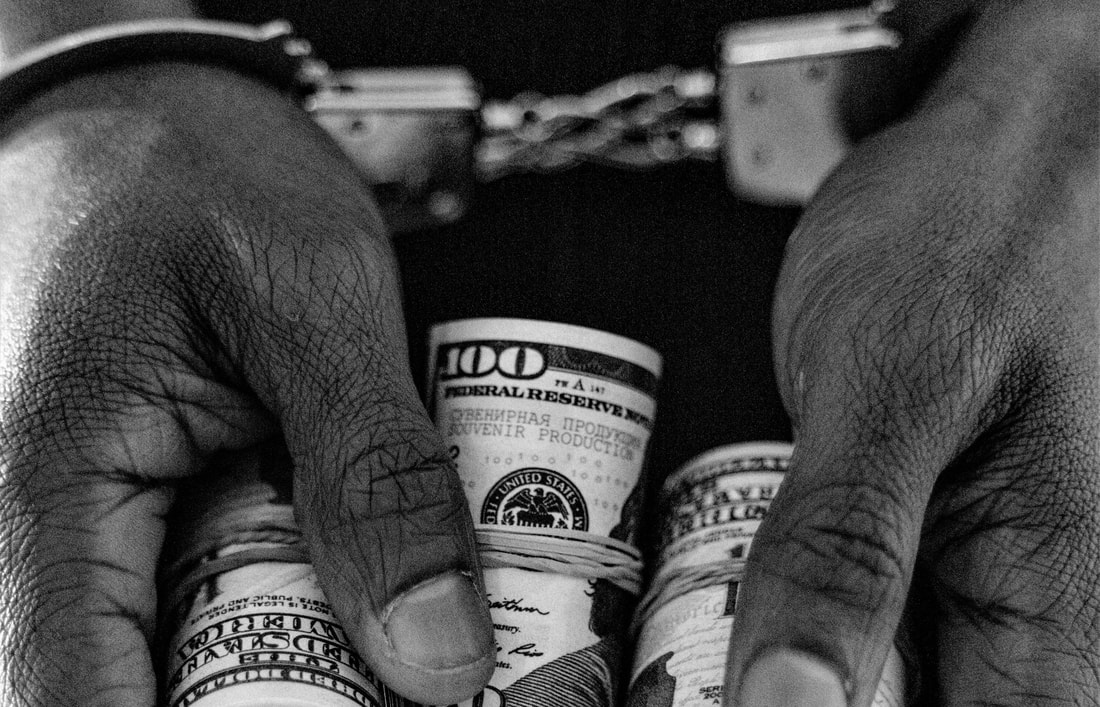

‘You could start a fight in an empty room, mate.’ (Allan Jones) I’ve never sought conflict. Far from it. I much prefer harmony and peace. That said, however, I can’t escape a similar calling to that which Martin Luther King once heard: ‘Stand up for righteousness! Stand up for justice! Stand up for truth!’ It’s a call that burns deeply inside of me and has done, as far as I can remember it, for my entire life. I’m pained to admit that I haven’t always followed that voice anywhere near as courageously as MLK. I haven’t always handled it with his astonishing humility and love. I’ve stayed silent when I should have spoken up or spoken up when I should have stayed silent. My words have stumbled out clumsily. I’ve caused pain where I meant to bring healing and hope. Yet, at times, this vocational stance has proved authentic, valuable and worthwhile. In my 30s, I worked for a large UK charity in the health and social care sector. As an idealistic young radical, I challenged the leadership team on numerous occasions when I believed we were compromising our values. I tried to do this with prayer and humility and out of a genuine desire to build relationship and trust. On one occasion, the leadership team decided, in view of limited budget, to increase only senior leadership salaries until it had secured sufficient funding to increase frontline staff salaries too. I argued vociferously that we should do the exact opposite – and to freeze my own salary as a first step. On another occasion, the leadership team decided to reserve all spaces in its small head office car park for executives only, given that they didn’t have time to drive around to look for parking places elsewhere. I advocated passionately that, especially in the winter months, the spaces should be reserved for female and other vulnerable staff or visitors so that they wouldn’t have to walk along dark city streets at night to their cars. On yet another occasion, the leadership team recruited a ‘hatchet man’ on temporary contract to implement a tough restructure with associated redundancies. I protested that this blunt way of approaching the change would damage relationships, engagement and trust. At times, I imagined my challenges and counter-proposals were met with deafening silence or heavy sighs – especially as I wasn’t a senior leader at the time. Nevertheless, when a serious crisis broke out between the leadership team and entire middle management, both sides to the conflict invited me to mediate as ‘the only person they could trust’. The chief executive, a man of remarkable humility, took me into his confidence and treated me like a respected thought-partner. When I moved on, the company secretary wrote to me to say he had never encountered such integrity. Even the dreaded ‘hatchet man’ wrote that he wouldn’t hesitate to employ me alongside him in any future role. Pray with humility – take a stance – speak the truth in love. ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.’ (Margaret Mead) ‘520,000,000,000’. I wrote the number slowly…and…deliberately across the whiteboard at the front of the class. The students looked on, intrigued. I asked, ‘Who can guess what this number means?’ The playful ones quickly put their hands up: ‘The population of the world?’ ‘The distance to the moon?’ I responded, ‘The number of Pesos (= US $8 billion) that people across the world spend on skin-whitening products in one year.’ The room was filled with looks and sounds of astonishment now. The students had considered this as a private personal-relational issue rather than a global economic one. This was part of a 3-day workshop for student teachers and social workers – that is, key influencers for the future – in the Philippines. The first time I had arrived in the country, I had been naively taken aback when one of the people who greeted me apologised for their skin colour. My Filipina co-facilitator explained that this is a common phenomenon, where people evaluate themselves and are evaluated by others for how dark or light their skin is. The students went on to share heart-breaking personal testimonies of how far this has impacted their lives, prospects and sense of worth. They were very surprised to hear how much money, by contrast, people in wealthy countries spend on products, treatments and trips abroad to darken their skin. I took some skin-tanning lotion with me from the UK to show them – and they could hardly believe their eyes. We went on to consider the deep cultural drivers and diverse vested interests that lay behind the skin-whitening industry. The lively debate that ensued generated novel campaign ideas to address stakeholders (e.g. manufacturers; marketers; retailers; consumers), and its damaging spiritual, psychosocial and financial effects. ‘If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine.’ (Ernesto Che Guevara) It looked like a scene from Dante’s inferno. Students from a very poor barangay (community) in the Philippines arrived home this week… Delete, rewind: arrived at where their makeshift homes had been until this week, to see them engulfed in a blaze of fire and billowing with thick, black smoke. The poor have no land rights, no insurance and no savings to fall back on. For a moment, it felt like their lives, as well as their homes, had gone up in flames. On hearing of this, one of their tutors, Jasmin, raced to provide them with emergency relief. She offered them a safe place to sleep in her own home, yet they refused – preferring to stay with their families in the midst of the charred and burned-out remains. On receiving her gift of food supplies, they immediately shared it with their extended families and with their neighbours who had lost all too. The next day, their fellow students rallied around in support. Rumours spread quickly that corrupt officials were behind the disaster as a way of driving the poor off the land to sell it to rich property developers – in exchange for a substantial bribe. Being sited at a prime seaside location, and being told immediately by the local Mayor that they would not be allowed to return, added sinister credence to these fears. The barangay residents have no access to justice, yet say they have Jesus as their advocate and hope. Life is hard-edged for the poor. We, too, can be hope. ‘Money – it’s a hit. Don't give me that do goody good bullsh*t.’ (Pink Floyd) ‘When I die, if I leave ten pounds behind me, you and all humanity may bear witness against me that I have lived and died a thief and a robber.’ (John Wesley) Now that’s extreme. In his lifetime, UK Christian preacher John Wesley is estimated to have earned around £30,000 (roughly equivalent to £1,000,000 today). When he died in 1791, 47 years after having written these astonishing words (above), he was found only to have a few coins left in his pocket. He had given everything away. Wesley believed that to follow Jesus meant intrinsically to use whatever resources God had given him to help others in need. He challenged fundamentally those who believed that material acquisition was a blessing from God to enjoy for their own benefit. As his own income increased, he stayed at the same simple baseline and gave even more away. I find Wesley’s example incredibly humbling and challenging. I live in a society that is individual-, wealth- and future-orientated. An implicit cultural imperative is that we should each make as much money as we can; both so that we can improve our own quality of life today and prepare for the future, confident that we will have plenty to spend then as now. I once had a long journey home from working among the poor in Cambodia. An intrigued Indian Hindu businessman travelling next to me on the plane confessed in bemusement that he found my work for a Christian NGO shameful: ‘Shouldn’t you be earning as much money as possible to increase your own family’s wealth?’ He had a point. To take care of one’s own family is, of course, an important, universal, human value. Yet, still, our worldviews collide. I find my life inspired by a different ethic, exemplified by Jasmin, a radical follower of Jesus among the poor in the Philippines: ‘Whatever status or power you have, use it for those who are vulnerable; whatever money you have, use it for the poor; whatever strength you have, use it for the weak; whatever hope you have, use to bring hope to those who live without hope. Speak up for justice and truth – whatever the cost. Pray.’ That isn’t about self-righteousness. It’s not a denial of the visceral tug of anxiety and security. It is about choice, decision and stance. What beliefs, values and principles guide your life? What do they look like in practice? ‘I could hear an inner voice saying to me, 'Stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth.’ (Martin Luther King: shot dead for preaching love, equality and peace). I feel sick. A 16 year old girl. Deemed: enemy of the state. Beaten to bloody death by insecure security forces, the brutal fisted hands and booted feet of a repressed, repressive regime. Her crime – now read this carefully because this is serious: she…burned…a…headscarf. Death penalty. No mercy from merciless leaders who claim so cynically to represent the merciful. Nika Shakarami. Remember the name. She shines as a bright emblem of resistance and hope, alongside Malala Yousafzai – the 15 year old girl shot in the head for daring, so shockingly, to say: it’s OK for girls to go to school. Remember too: Sophie Scholl, the 21 year old young woman, murdered violently by violent psychopaths for advocating non-violence in another era. God help us. Please pray. 'What is the true cost of a hoodie?' (Hannah Marriott) I hate it. She works in a textile factory in South East Asia, more commonly known as a sweat-shop, for £4.50 (US$ 6) per day. It’s long hours in sweltering conditions and arduous, back-breaking work. The little money she earns is barely enough to feed herself and her small children. If she, or they, get sick or injured, they're in deep trouble. With no discretionary income, she would need to borrow from a loan shark to pay for a doctor, medicine, or whatever else they may need. The extortionate fees and harsh interest rates make even the most rudimentary healthcare impossible, out of reach. The parent company, a well-known global brand, feels pressure from its customers to ensure that its clothing is produced ethically. Most consumers don’t wonder or ask how it’s possible we can buy a t-shirt in the UK for just £5 that was manufactured on the opposite side of the planet. Somebody, somewhere at the sharp end, is paying a heavy price. The company decides to visit the factory to carry out an inspection. On hearing this, the local HR manager calls all the employees, mostly women, together: ‘You will smile and tell them we pay you £10 per day and provide you with 3 healthy meals a day – or else.’ This half-whispered threat is far from idle. The women know that, if they were to blow the whistle, they would be dismissed as soon as the inspectors leave. That would plunge them and their families into even worse poverty, if that were possible, and there are plenty of other poor women outside willing to take their place. All the while, the local managers pocket the difference that the parent company intends for its workers. They wear smart clothes, live in nice houses and drive around in expensive cars. They know they can bribe any official to whom a desperate worker may dare to appeal. Money talks. Do we care? What can we do? Write to your MP (your political representative). Write to your favourite brand CEO. Check out: Clean Clothes Campaign; Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. ('The Asia Pacific region employed roughly 65 million garment workers in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, according to the International Labour Organisation. 80% of garment workers globally are women.' Tara Donaldson, WWD) It felt like something died inside today. The pain, frustration and powerlessness of experiencing a courtroom injustice first hand felt very different to toying with the notion as an abstract idea. The opposing party presented false evidence under oath yet our barrister was unprepared and the judge ruled in the opposition’s favour. I felt confused, angry, misrepresented, betrayed. It wasn’t only the loss of the case itself, it was something about a loss of innocence, a loss of faith in a system. How could truth and right be so easily swept away by a legal technicality? How could a judge be more concerned about protocol than the rights of an innocent party? As I drove home, I felt something stirring inside, an uncomfortable awareness of how far I've become numb to other people's experiences of vulnerability and injustice, in spite - or even because of - trying to address them through my work. I'm praying this experience today will inspire in me renewed empathy and greater passion to strive for change. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed