|

‘Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is one of the longest words in the dictionary, and ironically, it means the fear of long words. It originally was referred to as Sesquipedalophobia but was changed at some point to sound more intimidating.’ (Yalda Safai) You couldn’t make it up. Who would create a word like that – and why? One theory is that all professional fields create their own jargon, partly as a convenient shorthand for people working in that field and partly as an implicit status symbol. After all, if I know what the words mean and you don’t, that places me on a pedestal. It signifies I’m an expert – and you’re not. I did some work with a professional UK charity that wanted to change its brand tone of voice. (There you go: a bit of brand jargon). 'Tone of voice' means something like 'organisational personality'. Essentially, they wanted to change the way they express themselves in order to change the way in which they are perceived and experienced by those they want to work with. As part of the change, they decided to write in ways that one might ordinarily speak. It’s one of those curious cultural things in English, like in some other languages too, that we tend to write in one way and speak in another, even using different words to mean the same thing. Spoken words tend to be simpler and shorter. So, they set about de-jargonising their written jargon. Here are some examples they used to illustrate this principle, replacing written language with spoken – request: ask; require: need; advise: tell; retain: keep; endeavour: try; terminate: end. This made their communications feel less formal and more personal and conversational; especially when they also used first and second person (I/we/you) pronouns and active voice. (See how I slipped in a bit of grammatical jargon there?). So, language is important. A change of language can reshape the ways in which people and groups perceive, experience and relate to us, and to one-another. Language carries subtle emotional and cultural associations too, influencing how we (and others) feel, what we believe – and how we are likely to respond.

10 Comments

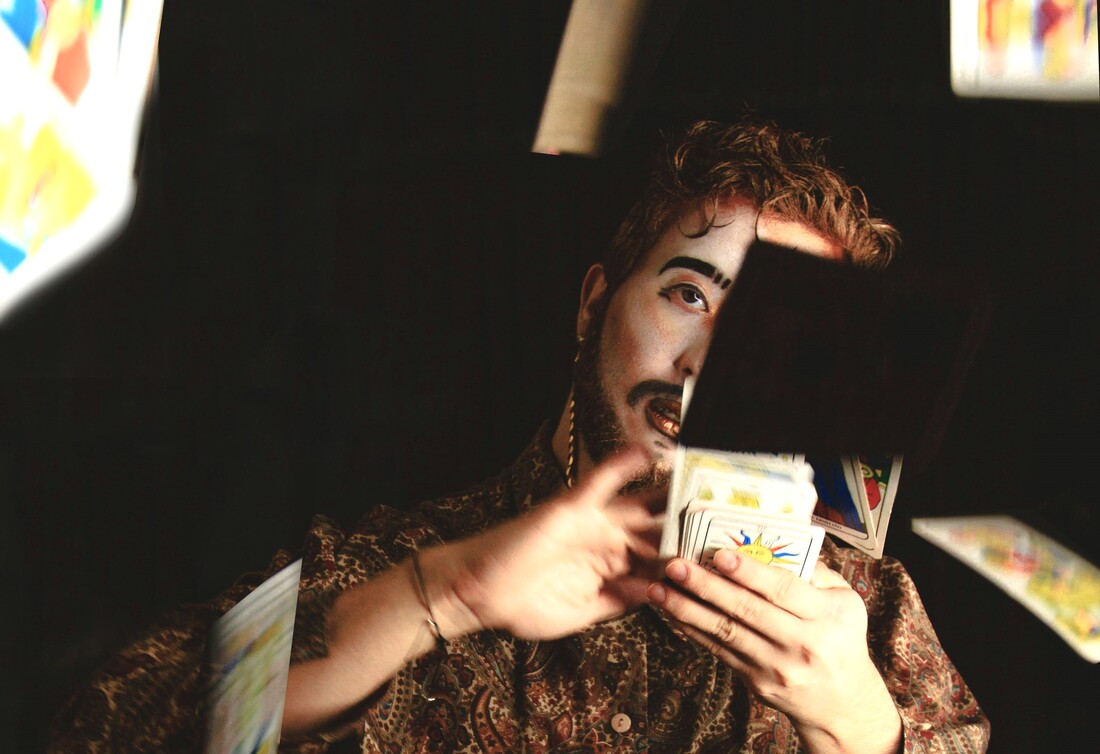

‘Uncertainty is the only certainty there is, and knowing how to live with insecurity is the only security. (John Allen Paulos) I had an important conversation with an impressive young woman from Malaysia this afternoon. As we shared examples of our various cross-cultural experiences with people and groups from different parts of the world, she mentioned an impact of a Judeo-Christian worldview on culture that I hadn’t really considered before. A belief that God created the world, both with a purpose and with a fundamental principle of order to it, leads to an assumption that things happen for a reason and, furthermore, that there are causal factors that lay behind whatever does happen. Take now, by contrast, an alternative and, say, fatalistic belief system in which things just are as they are. I remember speaking with a community development worker from the UK who worked with rural leather-working communities in Nepal. When he attempted to introduce methods such as adding lime during treatment to preserve the leather, and furthermore demonstrated the results, the local people didn’t appear to see any connection between adding of the lime and the absence of mould. It was as if whatever happened (or not) just happened (or not). Drawing a parallel, this woman today went on to comment that older generations often criticise the lack of stickability of today’s younger generations and attribute it to, say, fickleness, laziness or a lack of resilience. The former grew up with mantras such as, ‘If you study hard, you’ll get a better job’, or, ‘If you work hard, you’ll get a promotion/better pay.’ And often this was the case. Yet to young people now, the world looks and feels chaotic and unpredictable. It can often seem that to succeed (or not) is simply a matter of privilege or luck. 'So what’s the point of putting hard work in?' This contemporary contextual and cultural phenomenon is, alarmingly, a socio-psychological breeding ground for fundamentalist and reductionist ideologies, including in political spheres, that offer, as if by some divine miracle, a reassuring sense of simplicity, certainty, purpose and belonging. If a person or group feels all at-sea in life and an overwhelming sense of anxiety that may go with it, they may well grasp instinctively at and cling onto whomever presents a vision of safe and solid ground. Against this backdrop, false messiahs are emerging as leaders all over the world. ‘Is he – safe? I shall feel rather nervous about meeting a lion.’ ‘Safe? Who said anything about safe? Of course he isn’t safe. But he is good.’ (C.S. Lewis: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) I was 8 years old when the teacher asked us, a classroom of children, to sit on the floor while she read to us the next chapter of a novel, ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’. If you know the book, it was the part where Aslan the lion (which, I discovered later, the author had used to depict Jesus) appears in Narnia, a mythical world that represents this world. It's a beginning of real hope. This snow-covered land, which hitherto had been trapped under a curse of perpetual winter, is beginning to thaw. Meanwhile, the antagonist, an evil witch (depicting Satan), comes across a small group of woodland creatures enjoying a party to celebrate. She flies into a rage, interrogates them harshly and uses her magic powers to turn them into stone. At that awful and unexpected moment, I remember bursting into tears. As a child, I was horrified that, just as things had started to look up for these innocent animals, their lives and hopes had been shattered. It felt like a moment of despair for them – and for me. (A therapist-supervisor commented recently that little wonder most of my subsequent adult life has been spent in community work, human rights and international development). Today as I, along with Christians across the world, reflect on Jesus’ death on the cross, I’m reminded again of terrible injustice and violence against the innocent. I often identify more with Edmund than with Peter in Lewis' drama, yet what matters most is Aslan. It's He who breaks the power of the witch. ‘Chance is perhaps the pseudonym of God when he doesn’t want to sign.’ (Anatole France) I enjoyed a very tasty Eritrean meal with an inspiring young couple today. I had met this bright young man on a plane on my way to Germany last year and we had chatted throughout the flight. It turned out his equally-talented partner is involved in very similar work to my own, including internationally, so we agreed to keep in touch with each other on our return to the UK. As we met up again for the first time today, we talked about our shared faith in Jesus and his profound significance in our lives. We talked, too, about ways in which we’ve witnessed his mysterious power at work. As I listened to this couple's stories and experienced their generosity and warmth, I had a deep sense this encounter was far more than coincidence. When have you experienced encounters that somehow felt sacred? '95% of what we think we know, we have simply accepted from what other people have told us.' (Dennis Hiebert) Nothing adds up. How can we identify hidden assumptions, implicit agendas and vested interests that lay behind what we see, hear and read in the media? Perhaps the answer to this question has rarely been so critical. Democracy and social cohesion within and between peoples and nations are threatened by manipulation and misrepresentation of what we may ordinarily regard as truth. Following writer Mark Twain, actor Denzel Washington commented famously, ‘If you don’t read the news, you’re uninformed. If you do read the news, you’re misinformed.’ Take international news in the UK. Why are we so focused on Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Gaza? Why haven’t we noticed, apart from the occasional glance, the terrible civil wars in Sudan, Myanmar or Democratic Republic of Congo? Why do we call Russia’s brutal intervention in Ukraine a ‘full-scale invasion’? Why do we assume that increasing NATO size-spend is the only solution? If Israel’s bombing is indiscriminate, why has it killed, proportionately, so few ‘adult men’? Why didn’t we see outraged street demonstrations against horrific, widespread atrocities by Daesh? These are profoundly important, deeply complex and extremely painful issues and we rarely have access to the underlying research or information that could help us, as ordinary and concerned citizens of the world, to discern and decide how to act. We are presented with multiple, competing viewpoints and demands and this can feel both perplexing and paralysing. I don’t know the answers to such questions yet I do believe they should play at least some part in shaping my response. I will share some considerations that may help us to avoid sleepwalking blindness. As we’re exposed to news reports, what are we noticing and not noticing? How far does what we’re noticing appear to confirm what we already believe or want to believe? How open are we to having our assumptions, our preconceived beliefs and ideas, challenged to reveal something different or new? Why is the news presenter or media channel presenting this particular story or angle? What do they want us to believe, think, feel or do? Who or what is being excluded by the reporter’s narrative? Whose voice, perspective or experience is being ignored or filtered out? Behind the scenes: who owns and-or funds the media channel, the presented report or the research that underpins it? How rigorously are research methods tested to avoid implicit bias? Are views and experiences presented in a report genuinely representative of a wider and diverse population, or different sides to a conflict? In interpreting statistics, is a reporter presenting a case selectively, or cherry-picking results to show or advocate a particular stance? In short, be sceptical – and look for evidence that supports or contradicts the research-reporter’s ‘news’. ‘Relief distributions are a high-risk activity because managing large crowds in emergency settings is difficult and risky.’ (International Federation of Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies) Distressing and bewildering images in the media of besieged truck convoys, air drops and new maritime corridors into Gaza display the terrible human tragedy of this conflict and the complex challenges involved in distributing emergency relief. I’m sadly reminded of a new colleague in an international non-governmental organisation (INGO) many years ago who visited a famine-struck area to assess associated health and safety risks and ways to address them. It was his first time in a disaster zone and, to his horror, on arrival, he found the vehicles surrounded by a large crowd of desperate, shouting men; some openly aggressive, some armed with weapons. Colleagues in the vehicles carrying emergency food supplies were at the greatest risk, often having to hold back grasping people in an attempt to distribute the aid fairly and to those in greatest need. They could easily have been pulled off the trucks and injured or killed in the frenzied stampede. (He himself was dragged to the ground and barely survived). On listening to the most vulnerable people when things had calmed down, he was disturbed to discover extensive threats of violence, intimidation and sexual exploitation within the beneficiary community itself – highlighting the need for urgent, effective safeguarding. It was a tough learning experience. Another colleague from a different INGO visited another famine-stricken community in a very different country. Whilst travelling by jeep along muddy jungle tracks to reach a remote village which, according to a rapid needs assessment was in dire straits, he was stopped by men waving guns. They ordered him and his two colleagues to get out and to lay face down on the ground – then beat his companions over the head with rifle butts. Somehow, he survived. The men took their vehicle and their supplies and drove away. He discovered later that the attackers were from another nearby village, resentful that their community wasn't receiving the same support. The INGO world has learned a lot since then yet still has to grapple with incredibly stark human and logistical realities and choices. Please spare a prayer for those on the front line. ‘Well-behaved women rarely make history.’ (Laurel Thatcher Ulrich) International Women’s Day. A day to recognise and celebrate the extraordinary contribution of women all over this world and throughout all history. There are so many amazing women who have inspired, stretched and enriched my life: those I’ve known, those I’ve heard or read about and those I’ve only encountered indirectly through the personal-cultural legacy they’ve left behind. This is a shout-out, a thank you, to all women – especially to those who are and feel invisible and unseen; those who live on the frayed and torn edges of societies; those who persevere in the face of poverty, vulnerability and other threats; those who live and love in a way that goes unnoticed and unknown. You humble and challenge me. The world is a better place because you're here. ‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers) ‘Votes are cast based on rational decisions, right?’ (Zaria Gorvett) As I watched the former leader of a very influential nation speak on TV last night with what came across (to me, at least) as a mishmash of delusions and mistruths, I felt, to put it mildly, both bemused and dismayed. This felt even more so because current polls in that country point to a distinct possibility, if not yet a probability, that that person could actually be re-elected to that position of power. I found myself asking myself, ‘What kind of craziness would compel people to vote for this person? How can’t they see through the nonsensical and narcissistic rhetoric?’ Shaking my head with a deep sigh, I got up to make a cup of tea. Suddenly (I don’t know if it was the caffeine), a revelation hit me. I flashed back to some years ago in Germany, watching a 1-hour interview with Angela Merkel on TV. She was at the height of her leadership that year and, to be honest, I could hardly understand a word she said. My German language skills simply weren't up to it. Yet, somehow…I found her absolutely mesmerising. Something about her style, presence and tone subtly seduced me. I would have voted for her. I would have married her! Maybe. This took me back, next, to the Brexit-EU psychodrama in the UK. At that time, arguments flew back and forth vociferously in favour of Leave or Remain. Little I heard on either side bore much resemblance to evidential reality. Noticeably, most people I spoke with voted on instinct, on gut-feel intuition, and were swayed little by spurious claims or counterclaims. Boris Johnson, who won that game (by a narrow margin), played subconsciously on cultural memories of Winston Churchill, the lone hero who stood alone against overwhelming internal and external odds. So, an ex-President, an ex-Bundeskanzlerin and an ex-Prime Minister. It's far more than the words they say. It’s what they symbolise and represent. It’s how they make people feel. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed