|

‘Well-behaved women rarely make history.’ (Laurel Thatcher Ulrich) International Women’s Day. A day to recognise and celebrate the extraordinary contribution of women all over this world and throughout all history. There are so many amazing women who have inspired, stretched and enriched my life: those I’ve known, those I’ve heard or read about and those I’ve only encountered indirectly through the personal-cultural legacy they’ve left behind. This is a shout-out, a thank you, to all women – especially to those who are and feel invisible and unseen; those who live on the frayed and torn edges of societies; those who persevere in the face of poverty, vulnerability and other threats; those who live and love in a way that goes unnoticed and unknown. You humble and challenge me. The world is a better place because you're here.

40 Comments

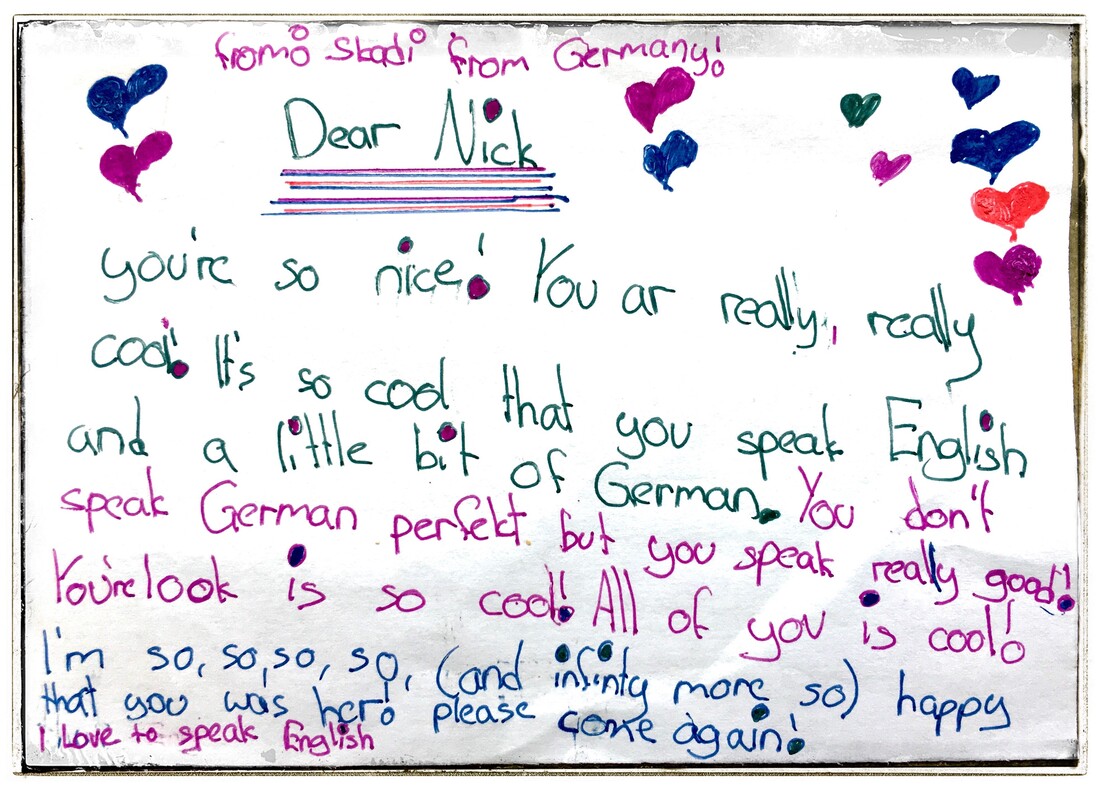

‘Our reality is narrow, confined, and fleeting. Whatever we think is important right now, in our mundane lives, will no longer be important against a grander sense of time and place.’ (Liu Cixin) I think you could say we’re a family with an international outlook. My parents travelled extensively around the world and have touched most continents. My older brother lived in Brunei, married a Malaysian woman and has visited almost every country in Asia. My sister lived in Germany, mixes with friends from different countries and travels frequently to Spain to do salsa dancing. My younger brother ran a charity for and in Romania, did a medical mission in remote areas of the Amazon jungle and works in Dubai. I’ve been interested in different languages and cultures from childhood, have worked in 15 countries and have visited, have friends in and have worked with people from a lot more. I watch almost exclusively international news, pay special attention to South-East Asia and my home is adorned with globes and colourful maps. Much of my life has been preoccupied with the Nazis and how to use my own life to help avoid anything like such horrific atrocities ever happening again. Against this backdrop, my own coach, Sue, posed two interesting challenges recently: ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – overseas with the poor and vulnerable in far-flung places yet to be, physically, here in the UK?’ and, ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – in World War 2 yet to be, physically, here and now?’ What great questions. They resonate profoundly, for me, with what it is to be a follower of Jesus – a deep dissonance that arises from being in this world, yet in some mysterious way being not of this world. Existentially, it’s a kind of dislocation that, a bit like for Third Culture Kids (TCK), creates a sense of being a child of everywhere yet, somehow, not a child of anywhere – at least in this lifetime. I often feel more at home when I’m away from home, a paradoxical dynamic that both draws and propels me into different times and places and to seek out God, diversity and change. It means being a traveller, not a settler, and has influenced every facet of my entire life, work and relationships. ‘Sometimes a language does exactly what we think it should; sometimes it goes places we don't like and thrives there in spite of all our worrying.’ (Kory Stamper) I taught English recently at a Montessori school in Germany. I was struck by the amazing level of conversational English of some of the students, and asked how it was possible that they could understand and speak so confidently and fluently at such a young age. Almost all replied that they have learned spoken English via online computer games, where they interact informally and socially with other young people from all over the world. English, for them, isn’t just another foreign language. It’s a form of linguistic currency that enables international communication, relationships, learning and fun. I find myself wondering what the impact will be over, say, 30 years of so many young people 'rubbing shoulders' with international English in this way. I won’t be around then to know the answer to the question, but I suspect that German, currently with 16 different ways to say, for instance, the English word ‘the’, will become simplified in common usage, so that speakers will start to use just one form of definite article in their own language too. We may also see conventions in other increasingly-international languages, such as Mandarin Chinese, influencing how other languages are used. What do you think? ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. I spent last week in Ethiopia, facilitating a vision-casting, relationship-building and insights-sharing event for an inspiring group of committed human rights activists from countries and contexts as diverse as: Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Kenya, Myanmar, Nepal, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States. Listening to their accounts of lived experience, alongside the oft-harrowing accounts of other people and communities too, was a deeply-sobering and yet, at times, life-giving experience. These activists are followers of Jesus from diverse backgrounds who commit their lives and expertise to help ensure, where possible, protection and support for people and groups facing unspeakable persecution. They often take considerable personal risks in the course of their own work too. One day, I went into a local town for a short break. A very poor, elderly man walked up and called out from behind me, a stranger. He grasped my hand, looked earnestly into my eyes and said, emphatically, “Whatever you need, reach out to God. He has the power to heal you.” Then, pointing upwards, as if to God, “He will give you whatever you need.” I felt completely entranced by this man’s presence. I asked his name. “ጥላሁን (Tilahun)”, he replied. I learned later it means: ‘shadow, guide, protector...’ This felt far more profound and spiritually-significant than a chance encounter. I returned to the work in a reflective mood, reminded of the mental and emotional burnout I had faced as a young human rights activist during the brutal civil war in El Salvador. At that time, my efforts had felt painfully impotent in the face of such overwhelming suffering. This mysterious figure reminded me to look upward as well as outward, and there beyond the heartbreak to discover transcendent hope. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed