|

‘To the victims of violence and betrayal, in the hope of an enduring peace.’ (Willy Brandt) Angelika gave me a gift this year of a shiny German 2 Euro coin. It was minted in 2020 to commemorate 50 years since West German Chancellor Willy Brand’s legendary ‘Kniefall’. I had heard of Willy Brandt but, I must confess, not the act that has, since, gripped my imagination. The German word Kniefall means, quite literally, to fall to one’s knees. I’m especially indebted to Valentin Rauer’s exceptional social-psychological study, Symbols in Action (2009), of what took place in that extraordinary moment in world history. I’m curious about what it meant and what made it so powerful. Brandt visited Warsaw in Poland, 25 years since the end of World War 2, on a mission to seek post-war reconciliation. Poland, including its Jewish population, had suffered horrific genocidal brutality at the hands of the Nazis. At the Monument to the Heroes of the Jewish Ghetto Uprising (against their Nazi oppressors in 1943), with a crowd of media reporters watching, Brandt suddenly and unexpectedly fell to his knees. He stayed there, in silence, as those around him looked on in amazement. It was an astonishing example of an action speaking far louder than words. At a political level Brandt, as Chancellor, represented West Germany. At a personal level, during the war, Brandt had been an anti-Nazi activist. The imagery of Brandt’s Kniefall, as an act of penitent humility that acknowledges guilt and seeks ‘forgiveness for an unforgivable past’ (Rauch), resonated deeply in a prevailing Christian culture. The symbolism of ‘the innocent (who) takes up the burden of the collective’s sin, thus redeeming the nation’ (Rauer) reflected Jesus Christ’s death on the cross. Brandt was in the square from which Jews were deported to concentration camps. For me, the most striking and moving dimension of this event was Brandt’s own reflection on the spontaneity and authenticity of his act: ‘Faced with the abyss of German history and the burden of the millions who had been murdered, I did what people do when words fail us.’ It paints the picture of a human being, beyond the public trappings of a politician, who allowed himself to feel empathy and brokenness, to take undefended responsibility and to reach out in peace. It transformed the trajectory of Cold War politics then. How desperately we need leaders like that now.

14 Comments

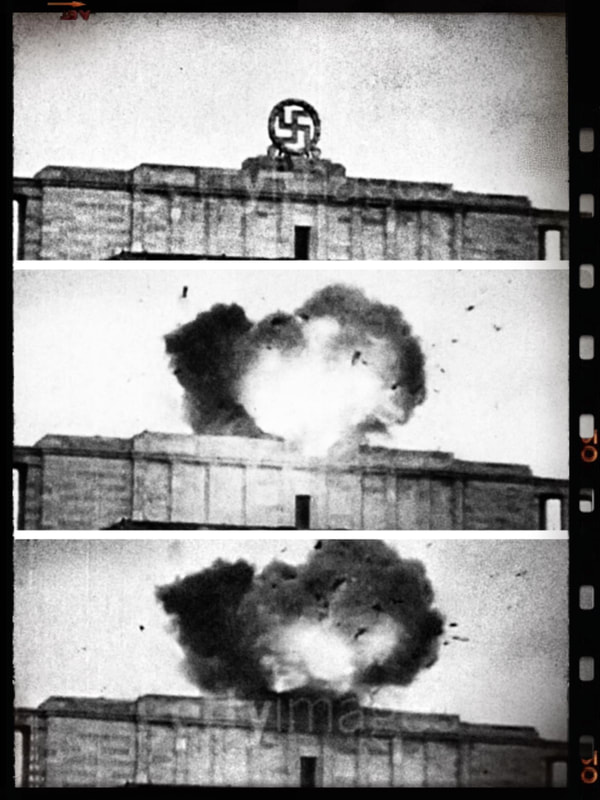

‘Life is like the harp string. If it is strung too tight it won't play, if it is too loose it hangs. The tension that produces the beautiful sound lies in the middle.’ (Gautama Buddha) In World War 2, when faced with a critical decision on how to respond to the Nazi threat, one of Winston Churchill’s advisers argued forcefully that ‘organisation is the enemy of improvisation’. This wasn’t a diatribe against the power of organisation per se. It was, however, deeply rooted in a belief that the UK’s main chance of success would be to act in ways that would capitalise on its own agile cultural traits – and leave the highly-organised German war machine disorientated and defeated. I’ve noticed there are parallels in learning a second language too. Students are often taught in highly-organised ways – focusing on vocabulary, grammar, reading and writing. It can provide them with a useful foundation, yet can also leave them completely paralysed in free-flow conversation. I’ve concluded that, at least in this respect, ‘Accuracy is the enemy of fluency.’ Remove the expectation to get everything right, distract from fears of making a mistake, and the words will start to flow. That said, I need to beware of unhelpful polarisation. Early in my OD career, I worked alongside an experienced HR consultant, Chris Rowe, who introduced me to a tight-loose principle. I had argued instinctively that an organisation needed to let go of its highly-organised, stifling structures and processes to become more flexible, responsive and innovative. Chris challenged me: there is a time for tight and a time for loose – and wisdom in knowing which, where, when and for whom. ‘Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.’ (Arthur Ashe) My first political act, with a capital P, was at the age of 14. I wrote to my MP (Member of Parliament) during the General Election that year to express my concern about the UK’s practice of retaining records that meant completed voting slips could be traced back to specific voters. It struck me as a profoundly anti-democratic practice, since a secret ballot was an important way of safeguarding freedom of political expression. My MP wrote back to explain that the practice was designed to track allegiance to extremist, anti-democratic far-right groups. That didn’t reassure me. Didn’t that mean we were adopting similarly anti-democratic practices too? He didn't respond. My next political act, this time with a small P, was to stand up in a Trade Union meeting, aged 19, in a packed town hall, and to challenge its politburo-style leadership. I was immediately shot down in flames by the enraged Union leader which, in spite of my trembling hands and voice as I spoke, simply confirmed my view that the Union had become thoroughly corrupt. It spurred me on to organise an organisation-wide petition aimed at reforming the Union by calling for a return to its political-ideological roots and values and to ensure greater fairness. I was confronted by apocalyptic warnings, by words like ‘you are playing with fire’, yet pressed on with the petition nonetheless. By age 22, my vision had turned international. I campaigned against the unspeakably violent actions of oppressive right-wing regimes in Central America that murdered the poor and vulnerable for daring to speak out. I was perplexed by the passivity or tacit collusion of those in power in the UK, US and beyond. Why weren’t we learning from history, from the sociopathic savagery of the Nazi regime through to the sick brutality of Vietnam? Why weren’t we more principled, more angry, more determined to stand up for what is right? I burned myself out with powerless passion. Yet learning to love would prove to be a harder challenge. The corruption I saw out there is also here in me. Few images have more powerful emotional resonance for me than that moment at which the WW2 Allies detonated explosives under a huge marble swastika at the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nürnberg, Germany. It was the place where, just before the war, Hitler and his followers had held their infamous Nazi rallies. The rallies had proved a potent propaganda weapon, convincing Nazi supporters of their own ‘supremacy’ and intimidating their enemies into fearful submission. The public destruction of this infamous symbol marked the impending final demise of the deranged Nazi myth and its psychopathic regime, and the end of by far one of the worst eras in human history. I can only imagine how it must have felt for those who had suffered so terribly to witness, at last, this emerging glimmer of hope. Similar evocative and symbolic moments were soon to follow with a Soviet flag over the German Reichstag and an American flag raised on Iwo Jima. There’s something about these images-as-symbols that capture and express a wider human story and experience. They carry and convey powerful psychological, cultural and emotional meaning for those who understand and identify with what they represent. Other well-known examples of symbols include the Christian cross as a sign of God’s love and salvation through Jesus Christ or, conversely, ominous ‘Z’ insignia on Russian military vehicles during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. What symbols have a particular resonance for you – and why? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed