|

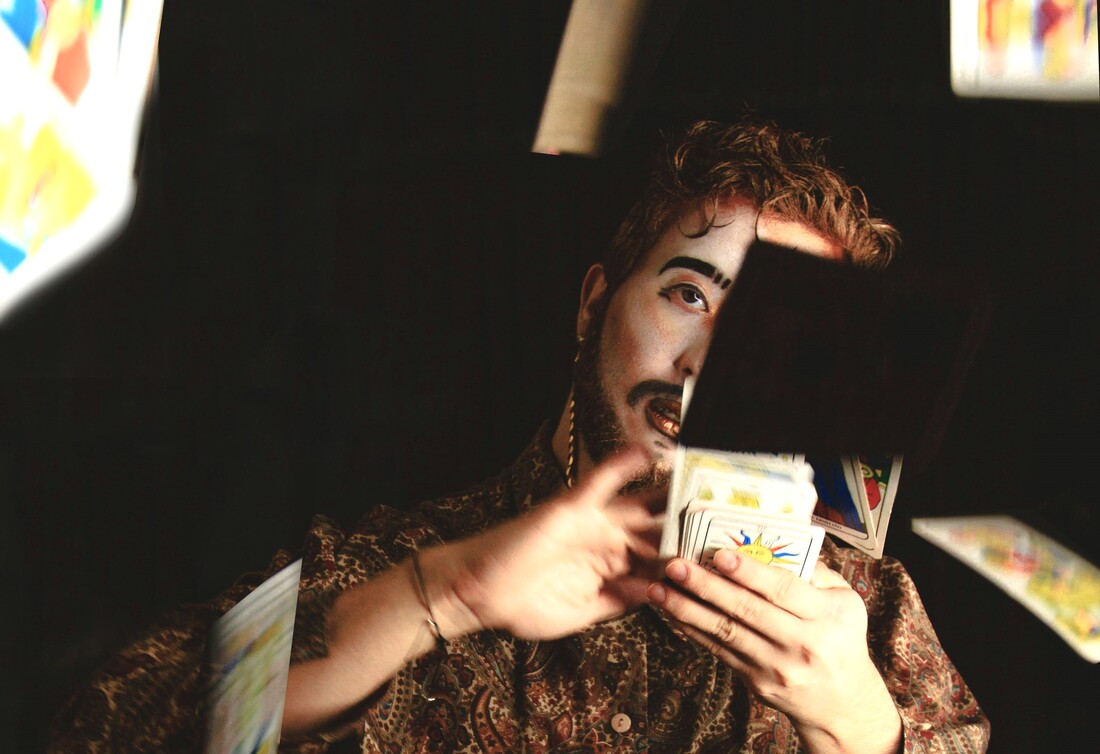

‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers)

10 Comments

'Growth occurs when individuals confront problems, struggle to master them, and through that struggle develop new aspects of their skills, capacities and views of life.' (Carl Rogers) A common consideration we face in coaching and action learning is, when asking a question, whom the question – or indeed the answer to the question – is for. For instance, if a person is describing a scenario in sketchy terms, we may be tempted to ask them to say more about it so that we have a better picture of the situation they have in mind. If they use jargon or acronyms with which we are unfamiliar, we may ask them to explain what they mean in order to fill our information gaps. If you work in a job such as a manager, professional or consultant, this approach to asking questions may sound and feel very familiar to you. It’s probable that you are employed in such a role because you’re an expert in your field and are able, therefore, to contribute. It may be that others come to you with tricky problems in the hope that you can solve them for them. It’s likely that you will ask questions that help ensure you’re able to offer an appropriate diagnosis, prescription or solution. Now turn this on its head. In coaching and action learning, I don’t need to know very much at all about a situation another person is talking about. My role is to help them to explore fresh avenues of thought and experience for themselves, in order to find or create their own innovative solutions. When I present this idea in training workshops, however, I often see participants look back at me with scepticism. ‘How are we supposed to pose useful questions if we don’t know anything?’ In one such workshop this week, I invited a group of online participants to engage in a simple experiment with me. I asked them to pay close attention, while I described a real challenge I’m dealing with. Before I began to say anything more about the issue itself, however, I turned off my microphone. Then, after a few minutes of speaking, I turned on my microphone again and asked them what questions they could now pose to help me think through my own issue more broadly or deeply. It was a lightbulb moment. After a few moments of silence, questions began to emerge. ‘Which aspect of this matters most to you?’ ‘If you were to be successful in moving ahead with this, what would that look like?’ ‘Which part of this is causing you greatest anxiety or concern?’ I then turned off the microphone again and spoke further. A few minutes later, microphone back on again…then another invitation for questions. The group paused again, then posed further questions to me. ‘Where are you at now in relation to your thinking about this?’ ‘How will you know if you have landed on the right decision?’ ‘What support will you need to move this forward?’ It was a powerful moment of realisation. As we reviewed together what had happened, some profound group insights emerged. ‘We didn’t get drawn into the issue with you because we didn’t know what you were talking about.’ ‘Our questions focused on you in relation to the issue, rather than on the issue itself.’ The client is the expert. My role is to help develop, release and apply that expertise to influence change. Curious to discover how I can help? Get in touch! This is a thought experiment. I choose these words deliberately, because a spirit of experimentation lays at the heart of Gestalt practice. It’s about learning by doing rather than, say, learning by thinking or learning by talking. That marks it out from conventional ways of coaching, facilitation and action learning (AL). It’s about trying something new, seeing what surfaces into awareness as we do so, then noticing any shift in our stance in relation to an issue we’re grappling with. It can be revealing, radical and powerful. Picture this. During an AL bidding round, each person depicts physically the essence of an issue that they’d like to work on. This could be, say, by standing and posing or acting out a scenario; drawing or painting a picture for the group to see; sharing an object that, for them, carries particular resonance with the issue they’re facing; presenting a song, poem, or piece of prose that expresses the core of the issue and any feelings they hold around it. The group then moves onto choosing a presenter. The choice of presenter could be influenced by, say, the felt sense of imminence or urgency in what a person has depicted; the degree of complexity that emerged as they sought to depict different dimensions; the scope for experimentation with actual changes in what that person portrayed. This would feel different to an ordinary rational evaluation of the relative merits of different bids and, instead, would call for courageous sharing of empathy, intuitions and gut-instinct discernment. At the exploration stage, the peers in the set would pose questions and reflections physically, by doing something that invites reflection and response from the presenter. This could be, for instance, to stand with the presenter, mirror his or her pose and ask them what they notice; move with the person to physical places where they can view their picture from a range of different angles; invite the person to act out any metaphors they had used in a song or poem then to see what emerges. Moving between exploration and action stages, the set would invite the presenter to try things imaginatively that could stretch the scenario and themselves in relation to it. This could involve, for instance, inviting the presenter to experiment with radically different poses to find one that best represents the stance they want to take; making drastic changes to the picture and noticing how that feels; reciting the song or poem using opposite metaphors to those they had used originally. This challenge phase of the Gestalt process is sometimes described as co-creating a ‘safe emergency’ with the presenter. It allows him or her to experiment with and experience, say, moving between extremes, or to very different places (physically; psychologically; systemically; emotionally) to where they might naturally prefer or default to. It enables them to push their own boundaries; to speak what may ordinarily feel unspeakable for them, to do what may normally feel un-doable for them. The final action stage would involve inviting the presenter to depict physically, say, their aspiration in relation to the issue they have presented; the physical stance that best represents that aspiration for them; any obstacles or enablers that they could envisage on route – using physical objects in the room (e.g. chairs) to represent them – then physically navigating through them; or physically to take what they choose as their next steps, adopting the posture or stance they will take as they do so. What have been your experiences of using Gestalt in Action Learning? I’d love to hear from you! [See also: Toys; Crab to dolphin; Let's get physical] ‘Think of your techniques as toys rather than tools.’ (Brian Watts) This was an insightful, inspiring and innovative coach who had a gift for working at the learning edge, the leading edge, the sometimes bleeding edge. I had the pleasure of working with him as a close colleague and as a client. For me, it was a profound, at times disconcerting, and yet often invigorating learning experience. It challenged my ingrained, default ways of thinking about and doing my work. It also gave me my first experiential taste of the power of Gestalt. His approach started with a simple and open invitation, ‘Be free, creative and experimental. See what happens. Let the child play!’ His conviction was that transformation takes place (a) through experiential learning, and (b) at what is, for the client, his or her own learning edge. It’s that frontier horizon at which we place our self- and culturally-imposed limits. It’s the stretched and stretching place where we may discover our own subconscious psychological defences too. I talked about a forthcoming meeting with an executive team. I was new in my career and found the anticipation of this encounter very anxiety-provoking. The coach invited me to leave the room, then to step back in as if entering the executive meeting room itself. When I did so, he observed (to my surprise) that I was holding my hand across my chest, as if protecting my heart. ‘How would it be if you were to reveal your heart in that meeting?’ I did so, and that transformed everything. In the creative, experimental spirit that lays at the heart of Gestalt coaching, he reminded me, ‘Sometimes these things will fall flat. It’s always a leap of faith.’ It’s a suck-it-and-see approach: try something new and see what may emerge into awareness. It taught me that learning has rational, emotional, intuitive, imaginative and somatic dimensions. I discovered I stand to learn most when I take a risk, when I dare to step out and beyond my natural-instinctive learning mode. Curious to experience the power of Gestalt? Get in touch! [For more examples of Gestalt coaching in practice, see: Just do it; Crab to dolphin; Let's get physical] ‘The willingness to experiment, it turns out, is the chief indicator of how innovative a person or company will be.’ (Hal Gregorson) Test and Learn is an experimental, adaptive technique, used to address complexity, uncertainty and innovation. It’s useful in situations where, say, past experience isn't a reliable guide for future action because e.g. critical conditions have changed. It’s also useful when moving into new, unchartered territory where the evidence needed for sound decision-making can only be generated by, ‘let's suck it and see’. It shares a lot in common with action research: create a tentative hypothesis, step forward, observe the results, try to make sense of them, refine the hypothesis, take the next step. Test and Learn is used in fast-paced, fluid environments, such as by rapid-onset disaster response teams where conventional strategizing and planning isn't realistic or possible. By the time a detailed plan is formulated, things have moved on - and the paper it's written on is sent for recycling before the ink has dried. Test and Learn is also used by marketing teams when testing new products or services or seeking to penetrate new or not-yet-known markets. It provides tangible evidence based on customer responses which, in turn, enables change or refinement before investing further. What psychological, relational and cultural conditions enable Test and Learn to work?

When have you used Test and Learn? How did you do it? What difference did it make? (See also: Unpredictable; Adaptive) ‘Question: Why do scuba divers always fall backwards out of the boat? Answer: Because if they fell forwards, they’d still be in the boat.’ (That meme still makes me smile). It takes me back to a recent conversation with an action learning group. We were practising a Gestalt technique of noticing use of metaphors as a person speaks, then inviting playful exploration to see what fresh insights and ideas might emerge. It has some parallels with James Lawley & Penny Tompkins’ symbolic modelling (Metaphors in Mind, 2000). Whilst thinking through an issue she was struggling with at work, one participant explained that she felt worried about ‘rocking the boat’. Picking up on the metaphor and stretching it towards a greater polarity, a peer asked, ‘How would it be if you were to sink the boat?’ Then, after she had had time to reflect and respond, another posed, ‘In that situation, what would it take to float your boat?’ In a Gestalt coaching context, I might invite the same person to enact the different metaphorical possibilities physically. We could use objects such as tables and chairs in the room to represent the boat and other significant people or situational factors, then experiment with rocking, sinking, floating or navigating through them. Doing it is very different to imagining it or talking about it. What experience do you have of working with metaphor? How do you do it? This impressed me. This woman has been deaf since birth and lip-reads. Struck by how naturally she speaks and with apparent ease in conversation, I'm curious and ask if she can hear anything of her own voice. She replies, ‘No - nothing’. Even more intrigued, I ask, ‘So…how do you know what volume you are speaking at?’ ‘Trial and error’, she replies. ‘I started to speak when I was a child. If someone leaned back as if trying to move away from me, I realised I was speaking too loudly. If they leaned forward as if straining to hear me, I knew I was speaking too quietly. Simple.’ And brilliant.

There are some interesting parallels to this approach in fields such as Gestalt coaching and OD action research. It’s about trying something new – an experiment, if you like – and being open to, sensitive to, the experience, the response. This type of feedback loop can enable us to learn, grow, innovate and improve. It takes courage to take a step into not-yet-knowing; attentive observation skills to notice what happens; critical reflective research skills to make sound, meaningful sense of it and, last but not least, personal and professional judgement to make good decisions and act on them. So, what does this point towards as leaders, OD, coaches and trainers? I believe it’s about recruiting, releasing and rewarding people who seize the initiative: responsible risk-takers willing to try something new, more likely to seek forgiveness than permission. It’s also about creating healthy relational and cultural conditions where positive qualities – e.g. wonder, curiosity and inquiry – thrive and are supported. It’s about experimenting and learning without fear of blame or failure. ‘There is no such thing as a failed experiment, only experiments with unexpected outcomes.’ (Fuller). ‘What language does a racoon speak?’ This young girl looked at me intently, clearly expecting an answer. I felt compelled to respond quickly, in the moment. ‘I don’t know. I guess…Racoonish?’ That seemed to satisfy her curiosity, at least for now. The thing that struck me most in this brief encounter was her wide-eyed, uninhibited enthusiasm for exploration, discovery and learning. She clearly felt unfettered by adult-type assumptions, e.g. by a belief that she should already know.

I sat in an HR team meeting where participants became preoccupied with how best to store annual leave request forms. They proposed various systems and procedures and evaluated them for their relative pros and cons. As the conversation progressed, along with the time it was taking for the team to resolve this, I felt increasingly curious and bemused and so interjected, quite innocently, ‘Why do you keep annual leave forms?’ Blank faces all around. Oh. End of that item. Move on. But what was going on here? These were bright people in professional roles. A real risk is that ‘professionalism’ can lead to ever-increasing demands for sophistication. Instead of asking simple questions, seeking simple solutions, we can become too complex, too complicated and miss key issues and ideas that lay hidden in plain sight. We associate child-likeness with childishness and therein lies a big mistake and a lost opportunity. Jesus said, ‘Be like children’. I say, ‘Amen.’ So here is a suggested antidote. A colleague describes coaching as the ‘art of the obvious’. There is important truth in that. When we face a situation, whether in leadership, OD or coaching, ask, ‘What would a child ask?’ (or even better, ask a child), ‘What’s the most obvious question that we’re not asking ourselves?’ e.g. ‘Why on earth are we doing this?’ Be willing to laugh and experiment too: ‘What would be the most radical, unorthodox, playful, creative solution to this?’ Give it a try! Look before you leap!

Conventional wisdom advises caution over spontaneous action. Think then do. It enables us to make considered decisions. It minimises risks. To do otherwise sounds foolish, reckless. And there are, of course, many situations in which this advice, this approach, rings true. Who, for instance, would embark on a radical venture without first preparing, looking at the pros and cons, counting the cost? Thinking before acting helps us to feel safer, more responsible. It’s about learning-before, weighing up options and implications then deciding a way forward. Just do it! Woah - by contrast, this sounds jarring, jolting. Act then reflect. Hold your breath and take a leap of faith. Do it and see what happens. Scary - but look…eyes blinking in bright light…this is where transformational power can really exert itself in coaching. Instead of, ‘How might it be if…?’, do it. Instead of, ‘I’m stuck in my thinking about this…’, stand up and show what ‘being stuck’ or ‘unstuck’ looks and feels like physically. Play, experiment. Notice what happens: insights and ideas for the next step forward, here and now. One step at a time. Trust the process. I once trained with Mark Sutherland, a supervisor and psychotherapist, who shared the image of a client as someone floating out at sea on a raft. Whereas some coaches may swim out to rescue the client, to pull the raft back to safer shores so to speak, Mark saw his role by contrast as simply joining the person on the raft: ‘Two people…wondering together.’ For many years now, I’ve found that image incredibly attractive and releasing.

A good friend and colleague, Ian Henderson (Eagle Training), uses a similar principle when drawing on NLP to evoke curiosity in a training group. He may open an event by telling an evocative story at the outset, without introduction or explanation, then stop the story at a critical juncture and shift focus to the formal agenda. It leaves the group surprised, confused and curious…and it’s that state of curiosity that draws the group into deep learning. A very similar principle attracts me to Gestalt, a coaching approach that involves active, physical experimentation with a client or group. The key to the experiment is to follow your intuition, support the client’s intuition, go with the flow, be playful and creative, let go of control. It means trusting the moment, the dynamic between you, and seeing what happens. I’m continually amazed by what surfaces into awareness and what changes take place. So picture the coach, the leader, the facilitator or trainer as someone whose role is to evoke curiosity, to enable the client, the team colleague, the group, to wonder. It is a child-like quality that can lead to all kinds of exciting adventures and discoveries. It entails suspending what we know, the pressure to know, and surfacing the power, the gift of not-knowing, allowing the unexpected to emerge – and noticing the newness that is revealed. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed