|

‘They may forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.’ (Maya Angelou) It was a dire and inspiring experience, a hospital for children with severe disabilities in a desperately poor country under military occupation. Conditions were severe, the children were abandoned by their families and the staff were often afraid, suspecting the children were demon-possessed and, therefore, holding them disdainfully at arms’ length. A fellow volunteer, Ottmar Frank, took a starkly different stance. He was a humble follower of Jesus and I have rarely witnessed such compassion at work. I asked him what lay behind his quiet persistence and intense devotion. He said, ‘I want to love these children so much that, if one of them dies, they will know that at least one person will cry.’ Ottmar’s words and his astonishing way of being in the world still affect me deeply today; the profound impact of his presence, and how my own ‘professional’ support and care felt so cold by comparison. I remember the influence he had on others too – how, over time, some others started to emulate his prayer, patience, gentle touch and kindness – without Ottmar having said a word. It invites some important questions for leaders and people, culture and change professionals. If we are to be truly transformational in our work, how far do we role model authentic presence and humanity, seeing the value in every person and conveying through our every action and behaviour: ‘You matter’?

40 Comments

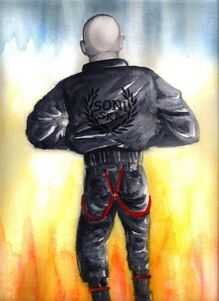

I think I saw an angel this week. I was walking into town the day after Christmas when I noticed a young man walking ahead of me, beer can in hand, dressed like a skinhead and looking decidedly rough. He stopped momentarily and stooped to the ground. I imagined he was going to drop his can at the roadside and I thought, cynically and silently, ‘Typical’. Instead, to my complete surprise, he picked up another empty can and continued walking. As we progressed, he picked up can after can, bottle after bottle, all discarded by revellers the night before. I was surprised, puzzled and intrigued. As we entered the town, I found myself continuing to follow him. He came to a rubbish bin and carefully dropped the cans and bottles inside it. Now I was really amazed. Instinctively, I felt in my pocket and pulled out some coins. Walking across the road, I smiled, held out the cash towards him and said, ‘Here - buy yourself a drink. I was so impressed to see you doing that.’ Now he looked surprised, puzzled and intrigued. ‘You don’t need to do that,’ he said shyly, ‘I’m just trying to look after my neighbourhood.’ I noticed wet blood across his knuckles, as if from a fight. A real paradox. He held out his hand and asked my name. I told him, asked his and he replied. We shook hands and parted ways. I felt nervous about the blood on my hands and, discretely, rushed off to find a place to wash. At the same time, I felt humbled, confused and inspired by this curious character. How quickly and easily I had judged him. How he was the one that had picked up litter, not I. How he did what was needed without seeking recognition or reward. How he modelled good citizenship without saying a word. I think I saw an angel this week. A true spirit of Christmas and a vision for a new year. When teams are under pressure, e.g. dealing with critical issues, sensitive topics or working to tight deadlines, tensions can emerge that lead to conversations getting stuck. Stuck-ness between two or more people most commonly occurs when at least one party’s underlying needs are not being met, or a goal that is important to them feels blocked.

The most obvious signs or stuck-ness are conversations that feel deadlocked, ping-pong back and forth without making progress or go round and round in circles. Both parties may state and restate their views or positions, wishing the other would really hear. If unresolved, responses may include anger/frustration (fight) or disengagement/withdrawal (flight). If such situations occur, a simple four step process can make a positive difference, releasing the stuck-ness to move things forward. It can feel hard to do in practice, however, if caught up in the drama and the tense feelings that ensue! I’ve found that jotting down questions as an aide memoire can help, especially if stuck-ness is a repeating pattern. 1. Observation. (‘What’s going on?’). This stage involves metaphorically (or literally) stepping back from the interaction to notice and comment non-judgementally on what’s happening. E.g. ‘We’re both stating our positions but seem a bit stuck’. ‘We seem to be talking at cross purposes.’ 2. Awareness. (‘What’s going on for me?’). This stage involves tuning into my own experience, owning and articulating it, without projecting onto the other person. E.g. ‘I feel frustrated’. ‘I’m starting to feel defensive.’ ‘I’m struggling to understand where you are coming from.’ ‘I’m feeling unheard.’ 3. Inquiry. (‘What’s going on for you?’). This stage involves inquiring of the other person in an open spirit, with a genuine, empathetic, desire to hear. E.g. ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘What are you wanting that you are not receiving?’ ‘What’s important to you in this?’ ‘What do you want me to hear?’ 4. Action. ('What will move us forward?’) This stage involves making requests or suggestions that will help move the conversation forward together. E.g. ‘This is where I would like to get to…’ ‘It would help me if you would be willing to…’. ‘What do you need from me?’ ‘How about if we try…’ Shifting the focus of a conversation from content to dynamics in this way can create opportunity to surface different felt priorities, perspectives or experiences that otherwise remain hidden. It can allow a breathing space, an opportunity to re-establish contact with each other. It can build understanding, develop trust and accelerate the process of achieving results. ‘What is most important about any event is not what happened, but what it means. Events and meanings are loosely coupled: the same events can have very different meanings for different people because of differences in the schema that they use to interpret their experience.’ These illuminating words from Bolman & Deal in Reframing Organisations (1991) have stayed with me throughout my coaching and OD practice.

They have strong resonances with similar insights in rational emotive therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. According to Ellis, what we feel in any specific situation or experience is governed (or at least influenced) by what significance we attribute to that situation or experience. One person could lose their job and feel a sense of release to do something new, another could face the same circumstances and feel distraught because of its financial implications. What significance we attribute to a situation or experience and how we may feel and act in response to it depends partly on our own personal preferences, beliefs, perspective and conscious or subconscious conclusions drawn from our previous experiences. It also depends on our cultural context and background, i.e. how we have learned to interpret and respond to situations as part of a wider cultural group with its own history, values, norms and expectations. A challenge and opportunity in coaching and OD is sometimes to help a client (whether individual or group) step back from an immediate experience and reflect on what the client (or others) are noticing and not noticing, what significance the client (or others) are attributing to it and how this is affecting emotional state, engagement, choices and behaviour. Exploring in this way can open the client to reframing, feeling differently and making positive choices. In his book, Into the Silent Land (2006), Laird makes similar observations. Although speaking about distractions in prayer and the challenges of learning stillness and silence, his illustrations provide great examples of how the conversations we hold in our heads and the significance we attribute to events often impact on us more than events themselves. He articulates this phenomenon so vividly that I will quote him directly below: ‘We are trying to sit in silence…and the people next door start blasting their music. Our mind is so heavy with its own noise that we actually hear very little of the music. We are mainly caught up on a reactive commentary: ‘Why do they have to have it so loud!’ ‘I’m going to phone the police!’ ‘I’m going to sue them!’ And along with this comes a whole string of emotional commentary, crackling irritation, and spasms of resolve to give them a piece of your mind when you next see them. The music was simply blasting, but we added a string of commentary to it. And we are completely caught up in this, unaware that we are doing much more than just hearing music. ‘Or we are sitting in prayer and someone whom we don’t especially like or perhaps fear enters the room. Immediately, we become embroiled with the object of fear, avoiding the fear itself, and we begin to strategise: perhaps an inconspicuous departure or protective act of aggression or perhaps a charm offensive, whereby we can control the situation by ingratiating ourselves with the enemy. The varieties of posturing are endless, but the point is that we are so wrapped up in our reaction, with all its commentary, that we hardly notice what is happening, although we feel the bondage.’ This type of emotional response can cloud a client’s thinking (cf ‘kicking up the dust’) and result in cognitive distortions, that is ways of perceiving a situation that are very different (e.g. more blinkered or extreme) than those of a more detached observer. In such situations, I may seek to help reduce the client’s emotional arousal (e.g. through catharsis, distraction or relaxation) so that he or she is able to think and see more clearly again. I may also help the client reflect on the narrative he or she is using to describe the situation (e.g. key words, loaded phrases, implied assumptions, underlying values). This can enable the client to be and act with greater awareness or to experiment with alternative interpretations and behaviours that could be more open and constructive. Finally, there are wider implications that stretch beyond work with individual clients. Those leading groups and organisations must pay special attention to the symbolic or representational significance that actions, events and experiences may hold, especially for those from different cultural backgrounds (whether social or professional) or who may have been through similar perceived experiences in the past. If in doubt, it’s wise ask others how they feel about a change, what it would signify for them and what they believe would be the best way forward. What is it that makes certain individuals stand out from the crowd? How is it that some people resist peer pressure, seize the initiative and radically break the mould? Is this kind of personal leadership, the ability to think freely, move proactively and act autonomously, something we should seek to attract and nurture in organisations? Could it release fresh energy, inspiration and innovation? The relationship between an individual, group and organisation is complex. Organisations as groups often foster consistency, continuity and conformity. We test people during recruitment for their potential fit, we induct and orientate people into the existing culture and we performance manage people to deliver preconceived products and services.

It’s a brave organisation that recruits and develops social revolutionaries, people who will instinctively challenge the status quo, think laterally, refuse to accept time-honoured traditions and push for something new. For leaders who operate in a conventional management paradigm, it can feel threatening, confusing and chaotic. The risks can seem too high and too dangerous. I worked in one organisation where we recognised our culture had become too settled, too complacent, too safe. People often commented on its warm, supportive relational nature but it lacked its former edginess, struggled to deal with conflict and desperately needed to innovate. The challenge was how to introduce and sustain a shift without evoking defensiveness. Social psychologists offer some valuable insights here, for instance in terms of social loafing and diffusion of responsibility where individuals are less likely to act independently or with the same degree of effort if they perceive themselves as part of a wider group where responsibility is shared. A challenge in this organisation was how to stimulate personal initiative and responsibility. Social conformity is another social psychological factor where people are likely to act consistently with the norms of a group if it provides them with a sense of acceptance and belonging within that group, or the approval of a perceived authority figure. A challenge in this organisation was how to ensure that personal initiative and responsibility were valued and affirmed. We took a four pronged approach. Firstly, we worked with the leadership team with a skilled external consultant known for his outspoken, courageous, challenging style to develop a more robust leadership culture, capable of open and honest conversations without fear that this would undermine relationships. This enabled the top team to model a new cultural style. Secondly, we introduced a simple behavioural framework that positively affirmed personal leadership in terms including personal initiative, personal responsibility, creative thinking and innovative practice. This framework was embedded into the organisation’s recruitment and performance development to attract, develop and reward these qualities and capabilities. Thirdly, we held an annual ceremony where staff were invited to nominate peers for awards where they had seen positive examples of such qualities demonstrated in practice. The peer aspect helped raise awareness and reinforce personal leadership as a cultural quality valued and affirmed by the organisation and to capture real stories that illustrated what it looked like in practice. Fourthly, we created a new innovation post, appointed an innovation enthusiast and allocated a new budget to stimulate and enable creative thinking and innovation across the organisation. This created a culture shift and a tangible symbol of the leaders’commitment to move in this direction. A willingness to question the status quo became a cultural value. A corresponding challenge was how to engender a spirit of personal leadership that took the wider system and relationships into account. If individuals only operated independently and didn’t take account of or responsibility for the implications of their decisions and actions on others, relationships would become strained, the organisation would become chaotic and it wouldn’t achieve its goals. To address this issue, we introduced the notion of shared leadership alongside personal leadership, emphasising and affirming the value of collaborative working alongside independent initiative. This too was reflected in the annual staff award ceremony and in recruitment, development and rewards. It was a matter of creative balance. As a tool for developing greater personal and shared leadership, I have found the following questions can be helpful: Who are my cultural role models? Who have I seen demonstrate great personal leadership? What can I learn from them? What would it take to contribute my best in this situation? What will I do to make sure it happens? In the past 12 months, where have I shown personal initiative? When have I held back from saying what I really thought or felt for fear of disapproval? What are the impacts of my actions on others? How far do I take responsibility to help others manage the implications of my decisions? How can I work collaboratively to achieve better win-win solutions? What difference do I want my life to make here? It was pouring with rain outside so it seemed only fair to offer the workmen a coffee. I’m not sure what they were doing, something to do with repairing the road, but they looked very cold and very wet. The leader of the group looked friendly and surprised as I approached them. ‘Nobody ever offers us a coffee…they just glare at us for blocking the road.’

One coffee with two sugars later, he looked quite emotional. The rain was streaming down his ruddy face. ‘I never wanted to do this job. It’s not how I imagined spending my life.’ Now it was my turn to look surprised. ‘I passed my 11+ but there weren’t enough spaces at the local grammar school. That simple fact determined my whole life…and here I am now. It’s so unfair.’ I was a bit taken aback by this sudden outpouring. I struggled to find something to say but the words didn’t come out. He turned and climbed back onto the truck. ‘Thanks for the coffee, mate.’ I walked back into the house, stirred by his story and reflecting on moments in life that can prove so pivotal, moments that often feel entirely outside our influence or control. I thought back to moments in my own life. Defining experiences, key people and relationships, music I’ve heard, things I’ve read, places I’ve been, studies I’ve undertaken, jobs I’ve done. Some felt like moments I created, others felt purely circumstantial, some felt like success, others felt like failure. It’s been a mixed experience and has shaped who I am. What’s your story? What stand out to you as the defining moments in your life? Who and what has shaped you most? What are the key choices or decision points that have led you to where you are now? Which moments have felt within your control and which have felt beyond you? Have you ever sensed the strange and mysterious, clear yet confusing hand of God? I spent this week with a Christian social worker friend in South Germany. At one point, we visited a project for older people who want to learn how to use new technologies. The project is led by a group of volunteers from a similar age group who act as trainers, mentors and advisers. This friend who manages the initiative entered the room, smiled and said hello to the group, introduced me then walked around the room, purposefully shaking hands and greeting every person individually with genuine warmth.

The thing that struck me most was his profoundly-felt presence in the room. He has an unusual talent for standing, moving and gazing in such a way that demonstrates he is really here and really now. It communicates a deep sense of being and being-with that extends beyond words. The act of shaking hands, of physical contact, felt more than a cultural ritual and created a profound sense of emotional and relational contact with the group. I felt spell bound by this person, this quiet charisma, this dynamic he evoked. It’s a sharp contrast with an approach to leadership, coaching or training that relies purely on professional competence or expertise. It’s so easy to lose contact with ourselves, God and others in the midst of the business of the day. We can become so preoccupied with a task that we lose sight of what really matters at a deeper human-spiritual level. As I watched this friend and felt his presence, I was reminded of words from the Bible: if I’m clever, competent and successful but do not love, I am nothing. (my paraphrase) So my challenge as I return to England is to reflect more on my presence; to have a clearer and more focused sense of my deepest beliefs and values; to take a more intentional and resolute stance in relation to others that demonstrates love, warmth, care and authenticity. I want to be more aware of when I behave in professional mode but lose sight of a person or group; when I allow myself to get so busy, so task-focused that I lose sight of my own and others’ humanity. In short, I want to be more like Jesus. What’s your theory of change? What issues are you trying to address? What creates and sustains those issues? What kind of interventions and when are most likely to prove successful? What would success look and feel like, and for whom? What is your overall goal? These are some of the questions we looked at on a Theory of Change workshop I took part in yesterday. Theories of change are becoming increasingly commonplace in the third sector, paralleling e.g. strategy maps in other sectors. There are a number of reasons for this. Charities and NGOs are under increasing scrutiny from supporters and funders to demonstrate how their resources are being used to achieve optimal impact. This has created a whole industry in impact evaluation.

The third sector is maturing too. No longer driven into action by empathy or altruistic instinct alone, organisations in this sector have more experience, more evidence of what works and what doesn’t and more analysis and understanding of why. The issues have turned out to be more complex than some had originally imagined, making significant and sustained progress challenging. Against this backdrop, a theory of change can prove valuable. It aims to clarify goals and outcomes and to work back to activities and other factors that will enable the outcomes to be achieved. In articulating these things clearly and succinctly (often in simple graphic flowchart form), underlying assumptions and causal links can be surfaced, explained and tested. At heart, a theory of change answers questions such as ‘What are we trying to achieve?’, ‘What is necessary for the goal to be achieved?’ and ‘What’s the rationale behind our intervention strategy?’ In doing so, it makes the organisation’s focus, operations and use of resources transparent, accountable and more open to challenge and improvement as new research and evidence emerges. I find myself particularly drawn to the critical-reflective aspects. For instance, one NGO I worked with conducted a fundamental strategy review starting with these same principles, asking questions such as, ‘Why are people poor?, ‘What causes and sustains poverty?’, ‘What interventions make the greatest difference?’, ‘What is our optimal contribution?’ One of the interesting challenges for a third sector organisation is whose voice is represented in framing and answering such questions, e.g. donors, beneficiaries, trustees, staff, volunteers. A charitable organisation I work with currently conducted a strategy review recently, inviting feedback from beneficiaries using surveys, focus groups etc. to find out what they struggle with and aspire to and what role they would want to see the organisation playing in helping them address or achieve these issues. The needs and aspirations that surfaced have been summarised as ‘I’ rather than ‘we’ or ‘they’ statements in clear and colloquial language, keeping the focus on what each individual as beneficiary wants to experience as a result of the organisation’s actions. This is a sharp contrast with some experiences I’ve had in the past. In one instance, a third sector organisation I worked with set up a drop-in project providing advice and support for long-term unemployed people. The Local Authority provided funding using ‘number of people using the service’ as its key success criterion. Paradoxically, the more successful the service was in enabling local people to find employment, thereby reducing the number of people who needed to access the service, the more the service was deemed statistically by the Local Authority to be failing. A theory of change can help surface such outcomes and assumptions at an early stage, enabling more constructive dialogue and agreement between agencies and stakeholders. I believe the potential for theory of change extends beyond third sector organisations aiming to articulate their vision, strategy, plans and reasons behind them. I’ve used similar methodologies to explore and articulate an organisation development strategy within a third sector organisation. We started by exploring a number of questions with diverse stakeholders and groups such as, ‘What kind of organisation are we trying to develop?’, ‘Where are we now?’, ‘Why are things as they are?’, ‘What drives or sustains how things are?’, ‘What matters most to people here?’, ‘Who or what influences change?’, ‘What would it take to achieve the changes?’ This enabled us to create a map showing goals, activities, assumptions and causal relationships. The same principles can be applied at team and individual levels too, e.g. for leadership, coaching, mentoring, training and counselling purposes. It enables dialogue between different parties and keeps rationale and assumptions explicit. If assumptions are clear to all parties, they can be challenged and revised in light of different preferences, perspectives, realities and evidence. I’ve used adaptations of this approach with people and organisations where Christian beliefs have been held as important and integral, developing the model as a theology of change. A theology of change may surface and articulate e.g. God’s purpose, values, presence and activity in the world, the role of the Spirit and Christians, discerning a sense of ‘calling’. In my experience, the language and methods of applying theory or change need to be adapted for different purposes and audiences. It represents a logical-rational paradigm that is likely to work well for some people and cultures but not so well for others. Using Honey & Mumford’s learning styles as one possible frame of reference, theory of change (as the name implies) may appeal most to people, teams or cultures with a theorist orientation. Reflectors may be attracted most by its emphasis on surfacing underlying assumptions, activists by the evidential dimensions and pragmatists by its focus on outcomes. Perhaps the key lies in using the principles it embodies flexibly and sensitively in the context of real human dialogue and relationship. ‘Live and let live’ sounds great until someone crosses the line or invades your borders. The man sitting next to me on the train this morning was an example, his feet spreading over into my foot space. I could feel myself tense up with irritation, ‘How could he be so annoying?’ In fact, I really dislike it when anyone crosses into my physical, psychological or emotional space uninvited.

It’s not that I’m an intensely private person. It’s something about protecting my freedom and control. I get stressed when someone plays their music or TV too loud, when kids kick the football against my house wall, when someone tries to manipulate or force me to do something. It’s as if these things feel like infringements on my freedom, my choices, my sense of autonomy. Khalil Gibran in The Prophet emphasises the value of space as essential for healthy human relationships. Psychologically, it’s about relating independently from a secure base in order to avoid unhealthy co-dependence or confluence. We could compare it recognising the necessary value of spaces between words and musical notes, enabling us to hear the lyrics and melody. In a work environment it could be about enabling space for people to express their own values, their own creativity, to innovate. It could be about ensuring people have their own desk space or time in their diaries to think. It could be about checking that roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and delineated to avoid confusion. It could be about avoiding risks of micromanagement. I’m reminded of a group dynamics workshop I co-facilitated with Brian Watts (www.karis.biz). Brian invited participants to stand opposite each other at a distance then slowly to walk towards each other until they felt they wanted to stop. It was fascinating to notice patterns in behaviour, how people felt as they moved towards, where they chose to stop in order to safeguard space. Typically in that group, women would stop at a greater distance to men than men would to women. In fact, a man would often continue walking towards a woman even after she had stopped, causing her to instinctively step back. Men stopped at a greater distance from other men and women stood closer to other women than they stood to men, or men stood to men. Personal space is also influenced by culture as well as gender and individual preference. Some cultures view such space as more important than others and people within cultures learn where to move, where to stop, where to place and uphold unspoken boundaries. It can create awkward tensions when people from different cultures navigate the spaces between them. My own spacial preferences reflect my personal disposition, my personality traits. The cultural dimension suggests that my ideas, experiences and feelings about space are socially constructed too. If I had grown up in a different cultural environment, I may well have learned to experience and negotiate space and boundaries very differently. Once conditioned, it’s hard to change. I guess the real challenge lies in how to enter and navigate space in a world where people with different values and preferences coexist and continually interact with each other physically or virtually, occupying the same or adjacent spaces. Perhaps it’s about how to create and safeguard the space we need without isolating ourselves, infringing on others’ boundaries or overriding others’ needs. What are your experiences of space? What are the anxieties and pressures that cause us to avoid or squeeze out space? How can we create space for ourselves and others in our lives, relationships and organisations? What are the psycho-social and spiritual costs of inadequate space? How do we balance space with pace? How can we learn to breathe? It was minus 7 so I got up early to scrape ice off the car windows. The journey to the train station that followed felt like torture. I got stuck behind a JCB for 10 miles with nowhere to pass. It reached a peak of 20mph and I kept glancing at the clock anxiously. Was I going to make it? I could feel the frustration like a tight knot in my stomach. Every passing moment felt like slow motion. I kept looking ahead, hoping for a clear stretch to overtake. It took forever. When I finally did get past, I felt like waving an angry gesture at the JCB driver. ‘How could you be such a *£%!&$* pain?!’

I left the car and jogged the final 10 minutes to the station. According to the clock, I’d missed the train but adrenaline spurred me on. On arrival, breathless, I discovered the train was running late. I caught it, stepped on board just as it pulled into the station. I sighed with great relief. Yet what a waste of nervous energy. The pressure I put myself under not to miss the train. The imagined exaggerated consequences if I were to arrive late. The risk of dangerous driving in icy conditions. My ungracious attitude towards the JBC driver. The life draining stress of an impatient journey. How much of my life I live under self-imposed pressure. The deadlines I create for myself. The expectations I place on myself. The determination to arrive on time, never to be late. The avoidance of risks that could lead to a mistake. The drive to do everything perfectly. The unwillingness to let a ball drop. The desire always to do well, never to fail. Such pressures can drive me inwards, close me down, cause me to lose contact with God, lose contact with people. It leaves me tired, stressed, anxious, irritable, frustrated and self-centric. It’s not the kind of person I want to be. I can almost hear God whispering to me, ‘Stop…look...listen...look up and around you…breathe…’ It’s about regaining perspective, keeping the most important things in view. Not losing sight of the people, the things, the issues, the actions that matter most. It’s about loosening my grip, learning to prioritise, learning to negotiate, increasing flexibility. I know these things in my head, I practice them in my work, but the experience this morning has flashed into consciousness with renewed energy and vision. It’s something about learning to live, to love and to know peace. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed