|

‘The art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery.’ (Mark Van Doren) This looks and feels so very different to my own school days. It has been fascinating to explore the spirit and approach to working with students at a Montessori school in Germany over the past few weeks. Laura, an English language teacher from Romania, sets out a creative range of different activities in a classroom. The children look around and choose whichever activity appeals most to them. Every activity involves doing something physical, not just thinking. I’m struck by how the teacher chooses to offer only minimal explanation. Each student works at their own level and pace and problem-solves for themselves, or with others, if they get stuck. The teacher is available – if needed. Kathrin, a maths teacher, invites the students to sit in a circle and introduces me, briefly. She invites the students to practise English by asking me questions directly, questions to which the answer must be a number. They ask, ‘How tall are you?’, ‘How much do you weigh?’, ‘What’s your shoe size?’, ‘What did your trainers cost?’ etc. We notice that the measures I use in the UK are different to those they use in Germany. This sparks curiosity and the students work out how to convert the numbers I give them into those that are meaningful for them. The teacher writes each number on a large sheet of paper, then uses those numbers as the basis for introducing a maths method for that day. Melina, also an English language teacher, from Mexico, works with those students who find learning difficult. She uses a creative range of short, energetic, and fast-paced techniques that capture and hold their attention. Again, I’m struck by the use of physicality in the activities she facilitates. She adopts an evocative elicitation-based stance, stimulating the students to lead the activities, to play an active role and to work out the answers for themselves. (I noticed my own temptation to step in if they got stuck and, paradoxically, how often they didn’t need my help – if I simply allowed them time and space to resolve their own challenges). I'm a student among students and I feel inspired.

12 Comments

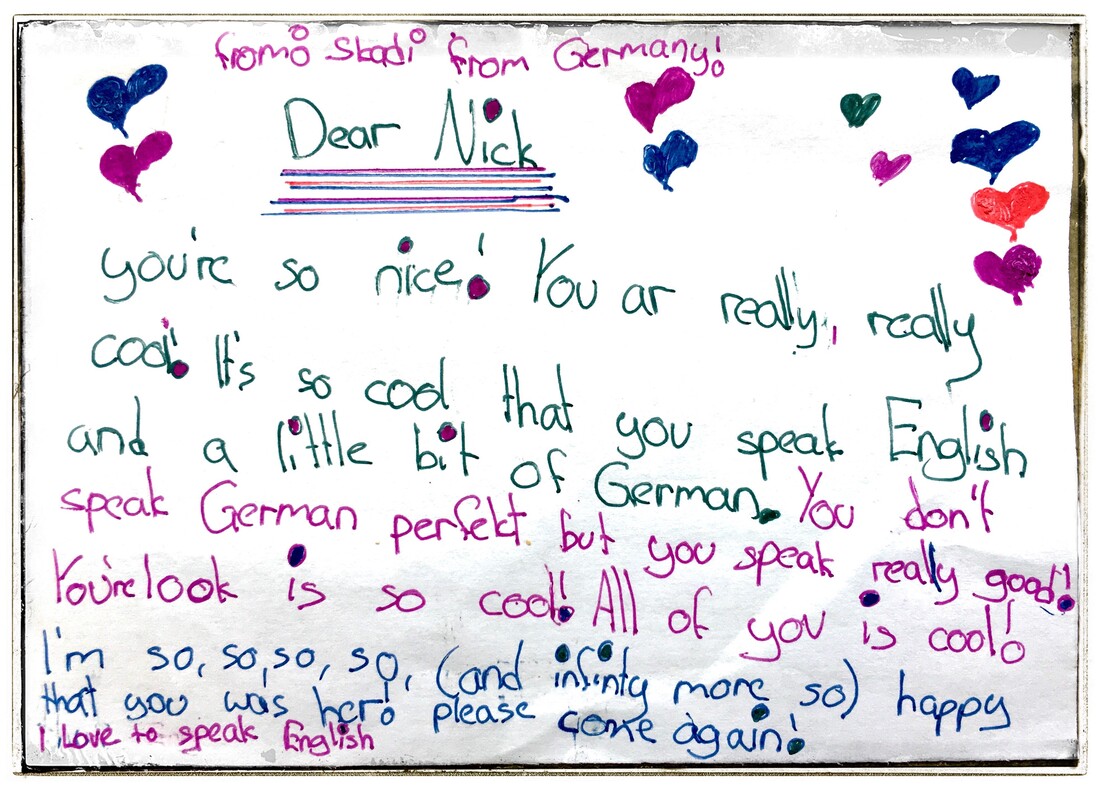

‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. I took my mountain bike for repairs last week after pretty much wrecking it off road. In the same week, I was invited to lead a session on ‘use of self’ in coaching. I was struck by the contrast in what makes a cycle mechanic effective and what makes the difference in coaching. The bike technician brings knowledge and skill and mechanical tools. When I act as coach I bring knowledge and skills too - but the principal tool is my self.

Who and how I am can have a profound impact on the client. This is because the relationship between the coach and client is a dynamically complex system. My values, mood, intuition, how I behave in the moment…can all influence the relationship and the other person. It works the other way too. I meet the client as a fellow human being and we affect each other. Noticing and working with with these effects and dynamics can be revealing and developmental. One way of thinking about a coaching relationship is as a process with four phases: encounter, awareness, hypothesis and intervention. These phases aren’t completely separate in practice and don’t necessarily take place in linear order. However, it can provide a simple and useful conceptual model to work from. I’ll explain each of the four phases below, along with key questions they aim to address, and offer some sample phrases. At the encounter phase, the coach and client meet and the key question is, ‘What is the quality of contact between us?’ The coach will focus on being mentally and emotionally present to the client…really being there. He or she will pay particular attention to empathy and rapport, listening and hearing the client and, possibly, mirroring the client’s posture, gestures and language. The coach will also engage in contracting, e.g. ‘What would you like us to focus on?’, ‘What would a great outcome look and feel like for you?’, ‘How would you like us to do this?’ (If you saw the BBC Horizon documentary on placebos last week, the notion of how a coach’s behaviour can impact on the client’s development or well-being will feel familiar. In the TV programme, a doctor prescribed the same ‘medication’ to two groups of patients experiencing the same physical condition. The group he behaved towards with warmth and kindness had a higher recovery rate than the group he treated with clinical detachment). At the awareness phase, the coach pays attention to observing what he or she is experiencing whilst encountering the client. The key question is, ‘What am I noticing?’ The coach will pay special attention to e.g. what he or she sees or hears, what he or she is thinking, what pictures come to mind, what he or she is feeling. The coach may then reflect it back as a simple observation, e.g. ‘I noticed the smile on your face and how animated you looked as you described it.’ ‘As you were speaking, I had an image of carrying a heavy weight…is that how it feels for you?’ ‘I can’t feel anything...do you (or others) know how you are feeling?’ (Some schools, e.g. Gestalt or person-centred, view this type of reflecting or mirroring as one of the most important coaching interventions. It can raise awareness in the client and precipitate action or change without the coach or client needing to engage in analysis or sense-making. There are resonances in solutions-focused coaching too where practitioners comment that a person doesn’t need to understand the cause of a problem to resolve it). At the hypothesis stage, the coach seeks to understand or make sense of what is happening. The key question is, ‘What could it mean?’ The coach will reflect on his or her own experience, the client’s experience and the dynamic between them. The coach will try to discern and distinguish between his or her own ‘stuff’ and that of the client, or what may be emerging as insight into the client’s wider system (e.g. family, team or organisation). The coach may pose tentative reflections, e.g. ‘I wonder if…’, ‘This pattern could indicate…’, ‘I am feeling confused because the situation itself is confusing.’ (Some schools, e.g. psychodynamic or transactional analysis, view this type of analysis or sense-making as one of the most important coaching interventions. According to these approaches, the coach brings expert value to the relationship by offering an explanation or interpretation of what’s going on in such a way that enables the client to better understand his or he own self or situation and, thereby, ways to deal with it). At the intervention phase, the coach will decide how to act in order to help the client move forward. Although the other three phases represent interventions in their own right, this phase is about taking deliberate actions that aim to make a significant shift in e.g. the client’s insight, perspective, motivation, decisions or behaviour. The interventions could take a number of forms, e.g. silence, reflecting back, summarising, role playing or experimentation. Throughout this four-phase process, the coach may use ‘self’ in a number of different ways. In the first phase, the coach tunes empathetically into the client’s hopes and concerns, establishing relationship. In the second, the coach observes the client and notices how interacting with the client impacts on him or herself. The coach may reflect this back to the client as an intervention, or hold it as a basis for his or her own hypothesising and sense-making. In the third, the client uses learned knowledge and expertise to create understanding. In the fourth, the coach presents silence, questions or comments that precipitate movement. In schools such as Gestalt, the coach may use him or herself physically, e.g. by mirroring the client’s physical posture or movement or acting out scenarios with the client to see what emerges. In all areas of coaching practice, the self is a gift to be used well and developed continually. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed