|

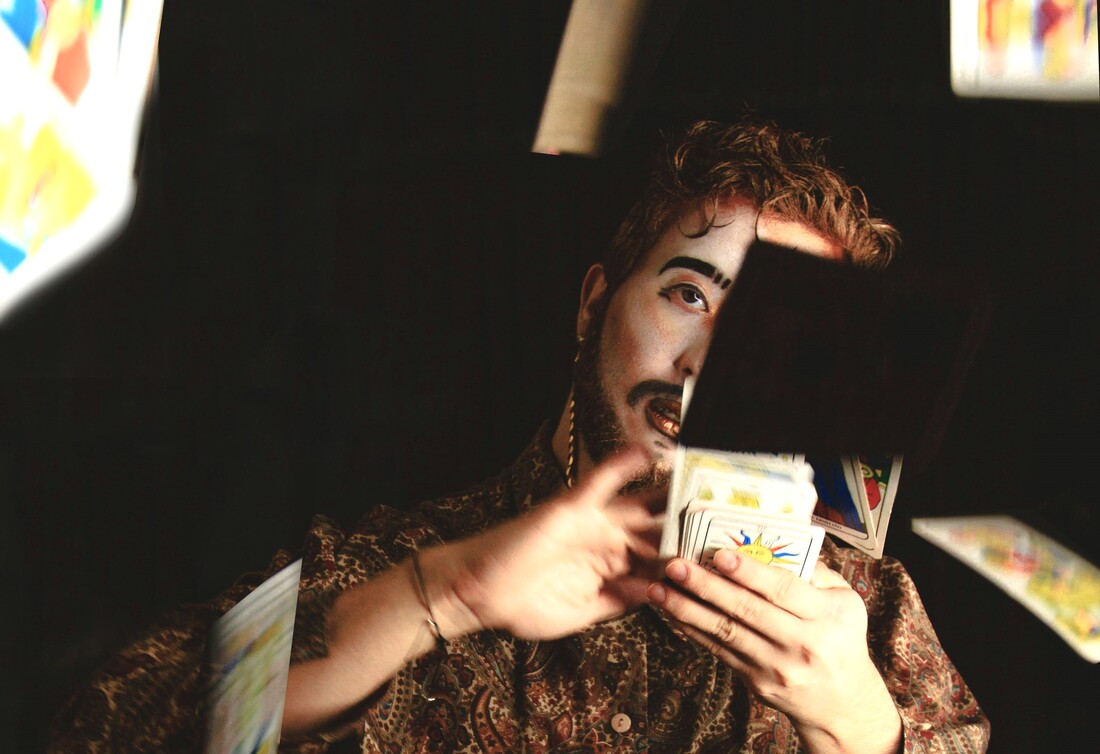

‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers)

10 Comments

‘To understand is to perceive patterns.’ (Isaiah Berlin) According to Gestalt psychology, human beings are hard-wired to see things in patterns. Take, for instance, a tree. If I were to invite you to imagine a tree, it’s likely you would imagine the whole tree (well, at least that part of the tree that is visible above ground). I wouldn’t imagine that you’d picture all its constituent elements separately – cells, leaves, twigs, branches etc. Unless you’re dissecting a tree in a botanical lab. It’s essentially the same idea in music. When we listen to a melody, we hear the tune as a whole, not each individual note separately from the others. In fact, if we were to examine each note in turn in isolation, it’s unlikely we’d be able to discern what melody they form part of when clustered together in a specific configuration. Except, perhaps, if we’re learning to play an instrument and focusing intently on one note at a time. Now this intuitive ability can be a real gift when working with teams, groups, organisations – or even making sense of geopolitics. It means learning to step back from the immediate issue or event and, metaphorically, to narrow our eyes into a near-squint to allow a bigger picture, a wider system, a deeper meaning, the wood for the trees, to emerge. Khalil Gibran observed, ‘the mountain is clearer to the climber from the plain.’ I recognised this phenomenon at work this last week when, in the Netherlands for the first time, the more I relaxed and allowed the language to flow over me, the more of it I could understand. When I paid too much attention to individual words, the more I got stuck. There are parallels in Timothy Gallwey’s Inner Game. Beware paralysis of analysis. Take a breath, relax your grip and notice what surfaces into awareness. ‘You can never really know someone completely. That’s why it’s the most terrifying thing in the world, really – taking someone on faith, hoping they’ll take you on faith too. It’s such a precarious balance. It’s a wonder we do it at all.’ (Libba Bray) There’s an idea in Gestalt psychology that we’re predisposed, hard-wired, to ‘fill in the gaps’. Here’s a real and practical example. I was once invited to facilitate a conference of around 50 people from diverse professional backgrounds in the housing sector. I had never met anyone in the group and they had never met me. I stood up on the podium, introduced myself simply as ‘Nick Wright, an organisation development consultant from England’, then invited everyone to take a pen and paper. I explained that I would ask them a series of questions about myself, to which they were to guess the answers. ‘Which newspaper do I read?’ ‘What political party will I vote for at the next General Election?’ ‘Am I married, or single?’ ‘What is my professional background?’ ‘What’s my favourite hobby outside of work?’ I then asked who had been able to answer every question. Everyone raised their hands. I now invited them to draw a simple face against each of their answers – which they wouldn’t be expected to share in the group. A happy face meant their answer drew them towards me; an unhappy face that it pushed me away. A neutral face meant, well, neutral. Again, everyone managed to do it. I paused and invited them to reflect at their tables on what had just happened. Person after person said how astonished they felt at how quickly and easily they had created a profile of me in their minds, and how that had influenced how they felt about – and were now likely to respond and relate to – me. They had filled in the gaps of not-knowing by drawing on hopes and fears, past experiences, personal projections, cultural assumptions etc. Filling in the gaps enables us to relate quickly to others rather than starting every relationship as if from scratch. It also risks unhelpful stereotyping and bias. This raised important questions for participants at the conference so I offered 3 principles: compassion, curiosity and challenge. Compassion: ‘What do I need to feel safe to contribute in this group? ‘How can I demonstrate a compassionate stance towards others?’ Curiosity: ‘What assumptions am I making about those around me, e.g. based on their looks, accent or job title?’ ‘Who or what is influencing the ways in which I’m thinking about, feeling about and responding to others?’ Challenge: ‘What am I not-noticing about those around me?’ ‘How open am I to have my beliefs about others tested?’ ‘When trouble arises and things look bad, there is always one individual who perceives a solution and is willing to take command. Very often, that person is crazy.’ (Dave Barry) We can think of leadership as the property of a structure, in which a person designated as a 'leader' holds particular responsibilities and has, at least in principle, the hierarchical authority needed to fulfil them. We can also think of leadership as an intrinsic property of an individual. In this sense, leadership is something that resides within and emanates from a person, something that she or he has and does. This is the realm of competency frameworks and of leader-development initiatives. We can also think of leadership as the property of a group; for instance, a leadership team. In this idea, shared leadership is something exercised by a collective, where a diverse united group is, in potential, more than the sum of its parts. We can also think of leadership as a property of a dynamically-complex eco-system, in which acts of leadership emerge, sometimes unexpectedly and from unexpected places, and exert influence. This is the arena of dispersed and distributed leadership. In organisations, I’m finding the latter perspective especially useful. When working with leadership teams, I invite participants to reflect on the eco-system (cf Gestalt: field) as a whole; for instance: 'Where is leadership-as-influence exercised, inside or outside of the organisation’s boundaries? What are the distinctive roles and responsibilities of different 'leadership' entities within the system? What are the relationships between them? What does each need from the others to be effective?' I notice this invariably opens up far deeper, wider and richer conversations than those that focus on individual leaders alone, or leadership teams in isolation, as if they exist in a cultural-contextual vacuum. Some people find it useful to experiment with mapping their eco-system graphically, recognising that any depiction will reveal and, therefore, create opportunity to open up to healthy exploration and challenge, the way in which they construe their reality and leadership dynamics within it. ‘I’m not a teacher, but an awakener.’ (Robert Frost) I imagine something like a coffee table between us. As the client talks about a challenge, issue or opportunity they are dealing with, I imagine them metaphorically painting a picture on the table, perhaps adding something like colourful photos from magazines, to depict their situation vividly. If, as a coach, I allow myself to follow the client’s gaze, to focus my own attention too on the scenario that is unfolding, I risk losing sight of the client. It may weaken the contact between us; draw us both into the place where the client already feels stuck; diminish the potential for transformation. How can I know if this is happening, if I have inadvertently become preoccupied with or seduced by the drama the client is presenting? Here are some tell-tale signs: ‘Tell me more about…’; ‘I’d be interested to hear more about…’; ‘Could you share a bit more of the background..?’ It could be that the client’s issue resonates with an area of interest, expertise or experience of the coach; or that the coach has subconsciously slipped into diagnostic-consultant mode, with a view to finding or creating a solution for the client. It’s as if, ‘If you give me enough information, I can resolve this for you.’ A radically different approach is to hold our attention on the client, to be aware of the figurative coffee table in our peripheral vision, but to stay firmly focused on the person (or team) in front of us. This is often where the most powerful coaching insights and outcomes emerge. Here are some sample person- (or team-) orientated questions: ‘Who or what matters most to you in this?’; ‘What outcome are you hoping for?’; ‘As you talk about this now, how are you feeling?’; ‘What assumptions are you making?’; ‘What are you not-noticing?’; ‘What are you avoiding?’; ‘Now that you know this, what will you do?’ This is a thought experiment. I choose these words deliberately, because a spirit of experimentation lays at the heart of Gestalt practice. It’s about learning by doing rather than, say, learning by thinking or learning by talking. That marks it out from conventional ways of coaching, facilitation and action learning (AL). It’s about trying something new, seeing what surfaces into awareness as we do so, then noticing any shift in our stance in relation to an issue we’re grappling with. It can be revealing, radical and powerful. Picture this. During an AL bidding round, each person depicts physically the essence of an issue that they’d like to work on. This could be, say, by standing and posing or acting out a scenario; drawing or painting a picture for the group to see; sharing an object that, for them, carries particular resonance with the issue they’re facing; presenting a song, poem, or piece of prose that expresses the core of the issue and any feelings they hold around it. The group then moves onto choosing a presenter. The choice of presenter could be influenced by, say, the felt sense of imminence or urgency in what a person has depicted; the degree of complexity that emerged as they sought to depict different dimensions; the scope for experimentation with actual changes in what that person portrayed. This would feel different to an ordinary rational evaluation of the relative merits of different bids and, instead, would call for courageous sharing of empathy, intuitions and gut-instinct discernment. At the exploration stage, the peers in the set would pose questions and reflections physically, by doing something that invites reflection and response from the presenter. This could be, for instance, to stand with the presenter, mirror his or her pose and ask them what they notice; move with the person to physical places where they can view their picture from a range of different angles; invite the person to act out any metaphors they had used in a song or poem then to see what emerges. Moving between exploration and action stages, the set would invite the presenter to try things imaginatively that could stretch the scenario and themselves in relation to it. This could involve, for instance, inviting the presenter to experiment with radically different poses to find one that best represents the stance they want to take; making drastic changes to the picture and noticing how that feels; reciting the song or poem using opposite metaphors to those they had used originally. This challenge phase of the Gestalt process is sometimes described as co-creating a ‘safe emergency’ with the presenter. It allows him or her to experiment with and experience, say, moving between extremes, or to very different places (physically; psychologically; systemically; emotionally) to where they might naturally prefer or default to. It enables them to push their own boundaries; to speak what may ordinarily feel unspeakable for them, to do what may normally feel un-doable for them. The final action stage would involve inviting the presenter to depict physically, say, their aspiration in relation to the issue they have presented; the physical stance that best represents that aspiration for them; any obstacles or enablers that they could envisage on route – using physical objects in the room (e.g. chairs) to represent them – then physically navigating through them; or physically to take what they choose as their next steps, adopting the posture or stance they will take as they do so. What have been your experiences of using Gestalt in Action Learning? I’d love to hear from you! [See also: Toys; Crab to dolphin; Let's get physical] ‘Think of your techniques as toys rather than tools.’ (Brian Watts) This was an insightful, inspiring and innovative coach who had a gift for working at the learning edge, the leading edge, the sometimes bleeding edge. I had the pleasure of working with him as a close colleague and as a client. For me, it was a profound, at times disconcerting, and yet often invigorating learning experience. It challenged my ingrained, default ways of thinking about and doing my work. It also gave me my first experiential taste of the power of Gestalt. His approach started with a simple and open invitation, ‘Be free, creative and experimental. See what happens. Let the child play!’ His conviction was that transformation takes place (a) through experiential learning, and (b) at what is, for the client, his or her own learning edge. It’s that frontier horizon at which we place our self- and culturally-imposed limits. It’s the stretched and stretching place where we may discover our own subconscious psychological defences too. I talked about a forthcoming meeting with an executive team. I was new in my career and found the anticipation of this encounter very anxiety-provoking. The coach invited me to leave the room, then to step back in as if entering the executive meeting room itself. When I did so, he observed (to my surprise) that I was holding my hand across my chest, as if protecting my heart. ‘How would it be if you were to reveal your heart in that meeting?’ I did so, and that transformed everything. In the creative, experimental spirit that lays at the heart of Gestalt coaching, he reminded me, ‘Sometimes these things will fall flat. It’s always a leap of faith.’ It’s a suck-it-and-see approach: try something new and see what may emerge into awareness. It taught me that learning has rational, emotional, intuitive, imaginative and somatic dimensions. I discovered I stand to learn most when I take a risk, when I dare to step out and beyond my natural-instinctive learning mode. Curious to experience the power of Gestalt? Get in touch! [For more examples of Gestalt coaching in practice, see: Just do it; Crab to dolphin; Let's get physical] ‘Respect deeply the otherness of the other.’ (Richard Young) Navigating boundaries is a critical skill in coaching and action learning. Anne Katharine describes this phenomenon succinctly in the subtitle of her book: Where You End and I Begin (2000). Incorporate Psychology provides a useful explanation of different kinds of relational boundaries and what can go wrong if they become blurred, enmeshed or rigid. Khalil Gibran writes poetically on this same theme in The Prophet (1923): ‘Let there be spaces in your togetherness. Let the winds of the heavens dance between you…Even as the strings of the lute are alone though they quiver with the same music.’ In coaching and action learning, a variety of boundaries emerge that we need to pay attention to for this work to be effective. In a coaching relationship, the coach and client learn to navigate these including: their respective roles and responsibilities; their places and times of meetings; their accountabilities to any wider stakeholders; the scope and parameters of what each will focus on, and not; their agreements on what will remain confidential, or not, and to whom. In action learning, further boundaries include those between facilitator and group, and those between different group participants and roles. At deeper human levels, Gestalt psychology speaks of confluence, where a boundary is dissolved and the quality of healthy contact is compromised. The coach and client, or action learning presenter and peers, need to differentiate between, for instance: what’s simply here-and-now and what’s transference from the past; what’s the coach/peers’ stuff and what’s that of the client or presenter; what’s just about the client or presenter and what’s a parallel process of wider systemic or cultural influences. Managing boundaries is, we discover, a key dimension to success in these fields. At a time when geopolitical tensions between NATO-EU and Russia are on the increase and depicted starkly as such in the media, I showed a video of a Russian 'hell march' to an international group and asked them: a. What do you notice; b. How do you feel; c. What does it mean? It opened a deep conversation that emphasised the need for critical reflexivity in interpreting experiences and events. A Chinese participant looked quite disdainful and said it reminded her of similar 'propaganda parades' in her home country, designed to make people feel compliant and positive about the Communist party state. A German participant said it filled her with fear, evoking stories she had heard from elderly family members about horrors under Soviet occupation at the end of the Second World War. A UK participant, perhaps with the spirit of Brexit still reverberating fresh in the background, said she found the enforced uniformity and conformity disturbing. A Filipina participant from an Hispanic cultural background, who had lived under a repressive military dictatorship, said she liked how the soldiers were as-if dancing to a rhythm and doing something constructive that displayed positive talent. I noticed banners in the background depicting 1941, the year in which the Nazis had unleashed a war in the East that resulted in unspeakable terror and devastation. As a passionate anti-Nazi, I saw the march as an assertive symbol: a 'never-again'. We reflected on our different selective perceptions, feelings and interpretations and the profound influence of ourselves-as-filters as we look out onto the world. In a similar vein, at a Gestalt coaching training workshop last week, I posted an image on screen of a tree in wheat field with dark clouds looming overhead. I asked the group what they would notice in 3 imagined scenarios: 1. As a child, you loved to climb trees; 2. You are walking the countryside and have forgotten to bring a raincoat; 3. You and your family have had no food to eat for a week. We noticed that we notice what matters to us in the moment. Different people-groups may notice different things in the same situation, or the same person-group may notice different things in the same situation at different times. We attribute meaning based on our beliefs, values, hopes, fears and expectations. This includes personal and shared-cultural memories, emotions and imaginations. As we move ahead this year, I pray that I-we will do so with eyes wide open. What may appear to us as self-evident, real and true may reveal as much about us as who or what we observe: if we are willing to see it. What can we do to create greater critical reflexivity? How can we address blind spots and hot spots to open up fresh possibilities, address risks – and take a stance that is sound? ‘Question: Why do scuba divers always fall backwards out of the boat? Answer: Because if they fell forwards, they’d still be in the boat.’ (That meme still makes me smile). It takes me back to a recent conversation with an action learning group. We were practising a Gestalt technique of noticing use of metaphors as a person speaks, then inviting playful exploration to see what fresh insights and ideas might emerge. It has some parallels with James Lawley & Penny Tompkins’ symbolic modelling (Metaphors in Mind, 2000). Whilst thinking through an issue she was struggling with at work, one participant explained that she felt worried about ‘rocking the boat’. Picking up on the metaphor and stretching it towards a greater polarity, a peer asked, ‘How would it be if you were to sink the boat?’ Then, after she had had time to reflect and respond, another posed, ‘In that situation, what would it take to float your boat?’ In a Gestalt coaching context, I might invite the same person to enact the different metaphorical possibilities physically. We could use objects such as tables and chairs in the room to represent the boat and other significant people or situational factors, then experiment with rocking, sinking, floating or navigating through them. Doing it is very different to imagining it or talking about it. What experience do you have of working with metaphor? How do you do it? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed