|

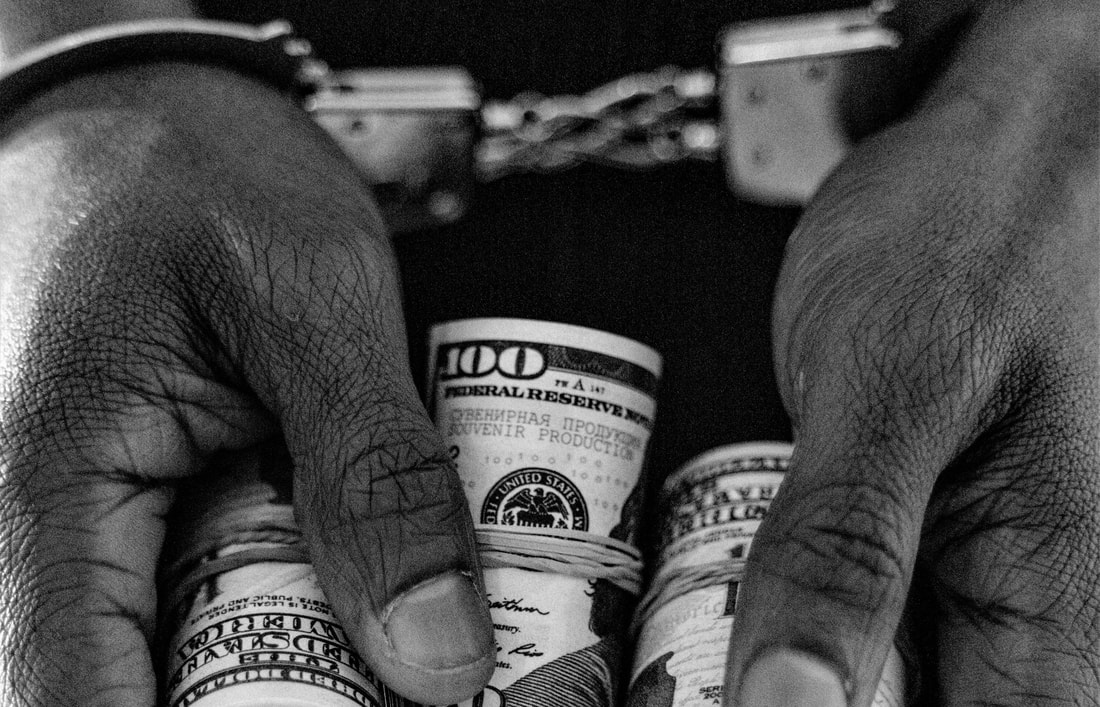

‘Money – it’s a hit. Don't give me that do goody good bullsh*t.’ (Pink Floyd) ‘When I die, if I leave ten pounds behind me, you and all humanity may bear witness against me that I have lived and died a thief and a robber.’ (John Wesley) Now that’s extreme. In his lifetime, UK Christian preacher John Wesley is estimated to have earned around £30,000 (roughly equivalent to £1,000,000 today). When he died in 1791, 47 years after having written these astonishing words (above), he was found only to have a few coins left in his pocket. He had given everything away. Wesley believed that to follow Jesus meant intrinsically to use whatever resources God had given him to help others in need. He challenged fundamentally those who believed that material acquisition was a blessing from God to enjoy for their own benefit. As his own income increased, he stayed at the same simple baseline and gave even more away. I find Wesley’s example incredibly humbling and challenging. I live in a society that is individual-, wealth- and future-orientated. An implicit cultural imperative is that we should each make as much money as we can; both so that we can improve our own quality of life today and prepare for the future, confident that we will have plenty to spend then as now. I once had a long journey home from working among the poor in Cambodia. An intrigued Indian Hindu businessman travelling next to me on the plane confessed in bemusement that he found my work for a Christian NGO shameful: ‘Shouldn’t you be earning as much money as possible to increase your own family’s wealth?’ He had a point. To take care of one’s own family is, of course, an important, universal, human value. Yet, still, our worldviews collide. I find my life inspired by a different ethic, exemplified by Jasmin, a radical follower of Jesus among the poor in the Philippines: ‘Whatever status or power you have, use it for those who are vulnerable; whatever money you have, use it for the poor; whatever strength you have, use it for the weak; whatever hope you have, use to bring hope to those who live without hope. Speak up for justice and truth – whatever the cost. Pray.’ That isn’t about self-righteousness. It’s not a denial of the visceral tug of anxiety and security. It is about choice, decision and stance. What beliefs, values and principles guide your life? What do they look like in practice?

20 Comments

‘The question is: how to ensure a healthy life-life, work-work and life-work balance?’ It felt like losing the plot. Spinning plates isn’t unusual or new yet, as a freelancer, the tell-tale signs were beginning to show. I met with my coach, Sue, to re-ground myself and my work before, like some scene from a Greek wedding, plates began to fall and smash in pieces around me. Sue asked me, ‘If you were to conduct an appraisal of your life and work for the past 12 months, what would the highlights be? How would you rate your life and business health and performance?’ My mind immediately went blank. I had allowed myself to become so busy that the year was a total blur. So, I sat down that evening, took out my diary and created a simple summary. I discovered to my surprise that I had worked with people from 150 organisations (charities; NGOs; churches; public sector, e.g. social services, health, education, police); from 35 countries; 60 coaching sessions; 30 training workshops; 25 action learning set meetings; written 25 articles and blogs; provided ad hoc TESOL support for refugees and asylum seekers; and, by God’s amazing grace and the generosity of family and friends, sent £23k in support to the poorest and most vulnerable in the Philippines. Strikingly, until I did this review, I had no idea. I had lost sight and sense of the wood in the midst of the trees. So, Sue asked me next what I enjoy most about this kind of work-life that I choose to live. I responded, ‘A sense of purpose as a follower of Jesus – and freedom.’ She came straight back with a challenge: ‘Where, for you, is the boundary between freedom and chaos?’ That hit the nail on the head, hard. Freedom is, for me, tied up closely with choice. I was at risk of becoming reactive, falling backwards. I needed to regain my balance, my grounded stance, to be truly free to choose again. Sue offered a suggestion. ‘How would it be if you were to set aside periodic ‘Creating Freedom’ days in your diary – to do those things (apart from your work) that you find life-giving and will help keep you grounded; or that will drain away your life and perspective if you don’t do them?’ That was a great insight and idea. That evening, I marked out spaces in my calendar for silent prayer, physical exercise, time with family and friends, holiday breaks; and for doing the headache-inducing financial and administrative parts of my life-work that I would otherwise procrastinate over or subtly avoid. That was my confession and solution. How do you ensure a healthy sense of purpose, perspective and priority in your own life and work? ‘Your choice point is the space you're in right before you make a decision.’ (Martha Tesema) You are choosing to read this blog – you could have chosen to do something else instead. You are choosing to read it now – you could have chosen to read it at a different time. In fact, according to psychological choice theory, everything you do is a choice. You’re not always aware of it and it won’t always feel like it. The implications and consequences of choosing one course of action over another can sometimes be so different and so stark that it can feel to, to all intents and purposes, as if there is no choice. Yet you are still likely to choose the action that, for instance, aligns most closely with your values; or has the greatest perceived benefits; or has the least risks or detrimental effects. The implications of this theory are radical and extreme. If every action you take represents a choice, and if you can grow in awareness of the choices you are making at each moment, a vast array of possibilities opens up to you. As you approach any decision, it will be like reaching a road junction, with always at least 2 options available to you. You will no longer be trapped or driven entirely by circumstances. You can exercise greater freedom and personal agency. You can learn to navigate adaptively through choices, like tacking into the wind on a sailboat. You can become more creative and innovative. You can visit places, reach destinations, that you never dreamed imaginable. There is a flip side. If you really are free to choose, you’re also responsible for your every action. It could feel easier to tell yourself that you have no choice – especially since you can’t anticipate every potential ripple effect. It would relieve you of the burden of accountability. You could also feel quite overwhelmed by the dread of having to make choices at every moment in time, in every situation. It could feel like existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre’s nightmare, ‘condemned to be free’. You may try to alleviate the anxiety by telling yourself that you’re a product of your background, upbringing, culture or circumstances. Then you could stop over-thinking, over-analysing, and get on with your life. So, how to handle this paradox? How to create the liberating freedom of expanding one’s sense and reality of choice whilst also to acknowledge the ethical and practical responsibilities it carries with it? First: awareness. Here’s a simple exercise. Write down a paragraph of no more than 100 words that describes the last meeting you had with a colleague. Now, underline every word that represents a choice point in what happened. If you do this rigorously enough, you will be amazed at how much of the text is highlighted. Now the stretch, a thought experiment: jot down at least 2 different choices you could have made at each choice point. Try to be creative and courageous as you do this. Second: responsibility. To build on this exercise, jot down a list of key criteria that will help you to ensure focus, priorities and boundaries to your decisions and actions. Here are some examples: ‘make best use of my time; achieve my career goals; develop the team’s potential; improve quality of relationships; create best value for stakeholders’. These criteria reflect and represent your values. Finally, test the actual choices you made, and the hypothetical choices you could have made, against these criteria to take note of what you could have done differently, what you could do next time and what lines you will not cross. Now – it’s your choice: given what you know now, what will you do with it? (See also: Choose; Choice; Agents of Change) What principles, beliefs or values guide your most important decisions? Olson (below) sounds a word of caution and Nickols offers a useful grid. Let me know what you think! ‘There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs.’ (Thomas Sowell) It was a critical juncture in my life so I met with a friend and mentor, Adrian Spurrell, to think things through. I had lots of ideas and some concerns but struggled to clear the mental fog that was amassing in my head. What to choose, what to do, when there are so many issues and options in the frame yet no clear and definitive way forward? Adrian challenged me by drilling down hard to my values, to what (for me) is non-negotiable and what isn’t, to sift the proverbial wheat from the chaff. The serious conclusions I reached in that conversation 2 years ago have guided my major life decisions since. This approach resonates with Dr Deborah Olson’s view in Psychology of Achievement (2017) who comments that: ‘When clarifying your goals, be clear about what you want – and consider the things you don’t want to risk.’ Don’t want to risk adds a useful and important dimension to more conventional goal-orientated conversations that focus solely on what we hope to obtain or achieve. I worked with one organisation where the founder lived an aspirational life and achieved amazing things at work but lost sight of his family. His daughter committed suicide. The ethical stakes can be very high indeed. Fred Nickols offers a simple and practical tool called a ‘Goals Grid’ that can be used to help identify goals and priorities (https://www.nickols.us/versatiletool.pdf) at personal, team and organisational levels. It poses two key questions: ‘Do I/we have it?’ and ‘Do I/we want it?’, places these questions on the axes of a 2-by-2 grid, adds the alternative responses of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ against each question and proposes an action for each domain. The resultant combinations and options are: Have + Want = Preserve; Have + Don’t want = Eliminate; Haven’t + Want = Achieve; Haven’t + Don’t Want = Avoid. Nickols’ model can be applied flexibly and creatively to incorporate a diverse range of helpful angles in leadership, OD, coaching and training conversations; e.g. strategic-visionary, spiritual-existential, psychological-relational and tactical-systemic. It ensures that trade-offs are made as conscious decisions with transparency and awareness. It also reminds that, when reaching towards a brighter future, to notice, value and protect who and what matters most. ‘Not jeopardising what we already have can matter as much as gaining new things.’ (Olson, 2017). Always keep values in sharp view. ‘The subtle art of not giving a f*ck.’ (Mark Manson) The title grabbed my attention first – and it made me laugh! I loved the subtlety in its provocative unsubtlety. The subtitle: ‘A counterintuitive approach to living a good life’ caught my interest too. The central premise is that if we allow ourselves to care too much about too much – rather than, by contrast, discerningly about the people and things that really matter – we risk suffering undue stress, anxiety or depression. An important dimension of resilience is learning when not-to-care. I’ve experienced this phenomenon at work. It was a leadership team meeting and the MD decided to take the whole team through an incredibly detailed, RAG-rated KPI grid alongside a micro-detailed financial spreadsheet line by line, cell by cell. I thought I was going to die. The organisation was struggling and the Director was convinced that tight management was needed. As we laboured through it point-by-point, it felt like all the oxygen had been sucked out of the room. Agony. Or there’s the worried client who asks for coaching because he or she has become paralysed in a tricky relationship and can’t see a way through. The conversation starts and, as minute pass by and the details keep flowing without stopping for breath, it becomes clear that he or she has lost all sight of the metaphorical wood for the densely-crowded proverbial trees. ‘What really matters to you in this?’ can help pull the person out of the detail, back to the bigger picture. Pause. Breathe. The principle here is: ‘Don’t sweat the small stuff’. It’s about perspective, focus and boundaries and it reflects beliefs, values and culture. It’s influenced by and influences emotional states. It’s not a nihilistic call to ‘Don’t give a f*ck about anyone or anything’. It’s about diving below, rising above, filtering, seeing through. As leader, coach or OD, how do you help people and teams discover who or what matters most? How do you enable clients to discern or decide an authentic sense of priority? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed