|

‘Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is one of the longest words in the dictionary, and ironically, it means the fear of long words. It originally was referred to as Sesquipedalophobia but was changed at some point to sound more intimidating.’ (Yalda Safai) You couldn’t make it up. Who would create a word like that – and why? One theory is that all professional fields create their own jargon, partly as a convenient shorthand for people working in that field and partly as an implicit status symbol. After all, if I know what the words mean and you don’t, that places me on a pedestal. It signifies I’m an expert – and you’re not. I did some work with a professional UK charity that wanted to change its brand tone of voice. (There you go: a bit of brand jargon). 'Tone of voice' means something like 'organisational personality'. Essentially, they wanted to change the way they express themselves in order to change the way in which they are perceived and experienced by those they want to work with. As part of the change, they decided to write in ways that one might ordinarily speak. It’s one of those curious cultural things in English, like in some other languages too, that we tend to write in one way and speak in another, even using different words to mean the same thing. Spoken words tend to be simpler and shorter. So, they set about de-jargonising their written jargon. Here are some examples they used to illustrate this principle, replacing written language with spoken – request: ask; require: need; advise: tell; retain: keep; endeavour: try; terminate: end. This made their communications feel less formal and more personal and conversational; especially when they also used first and second person (I/we/you) pronouns and active voice. (See how I slipped in a bit of grammatical jargon there?). So, language is important. A change of language can reshape the ways in which people and groups perceive, experience and relate to us, and to one-another. Language carries subtle emotional and cultural associations too, influencing how we (and others) feel, what we believe – and how we are likely to respond.

10 Comments

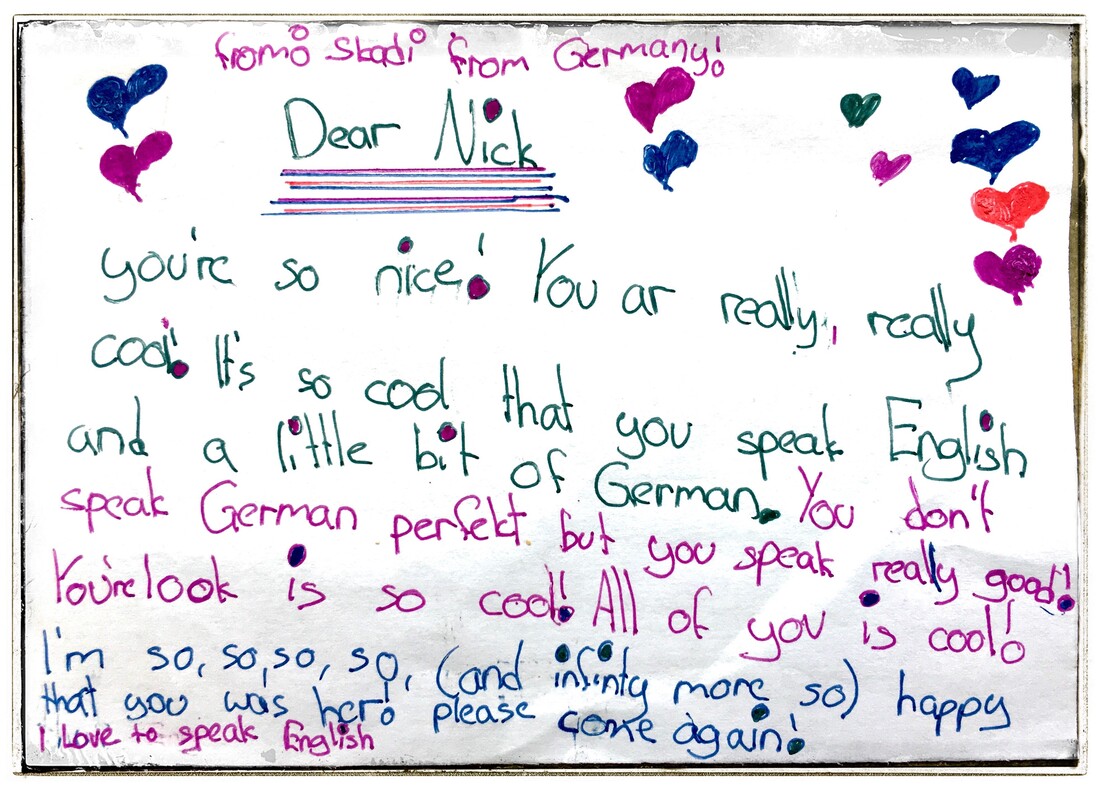

‘Sometimes a language does exactly what we think it should; sometimes it goes places we don't like and thrives there in spite of all our worrying.’ (Kory Stamper) I taught English recently at a Montessori school in Germany. I was struck by the amazing level of conversational English of some of the students, and asked how it was possible that they could understand and speak so confidently and fluently at such a young age. Almost all replied that they have learned spoken English via online computer games, where they interact informally and socially with other young people from all over the world. English, for them, isn’t just another foreign language. It’s a form of linguistic currency that enables international communication, relationships, learning and fun. I find myself wondering what the impact will be over, say, 30 years of so many young people 'rubbing shoulders' with international English in this way. I won’t be around then to know the answer to the question, but I suspect that German, currently with 16 different ways to say, for instance, the English word ‘the’, will become simplified in common usage, so that speakers will start to use just one form of definite article in their own language too. We may also see conventions in other increasingly-international languages, such as Mandarin Chinese, influencing how other languages are used. What do you think? 'Language is a process of free creation.' (Noam Chomsky) A talented linguist and disciple of Noam Chomsky invited Jacob, a young German student, to reflect on which of two sample sentences in English was correct. Jacob was unsure about the exact meaning and structure of the phrases yet, gesturing with his hand to his chest, he then pointed thoughtfully at one and said, ‘I don’t know, but it feels like it’s this one.’ I was stunned. He was correct, and he didn’t know how or why. The teacher explained. Jacob has been exposed over time to English via e.g. social media, computer games etc. He somehow knows the answer; less analytically and more intuitively. I flashed back in my own memory to a time when, as a teenager, I was learning French at school. I had a hunch, an idea, that if I played French radio in the background in my room, I too would become tuned into the language even if I didn’t understand anything that was being said. Over time, I did start to distinguish one word from another, then to notice recurring words, then to become aware of the contexts in which certain words or phrases were used. I started to hear the accent, word stress and intonation. It wasn’t a conscious process so much as, like an infant child, a learning of language by immersion. This linguist then invited a wider group of students to play a fast-paced game that involves using lots of different words in English. They didn’t necessarily know or understand the words and the teacher, a speaker of five languages, didn’t translate them. I was puzzled by this and asked why. Pointing to Chomsky, she took me back to the same core principle I had discovered for myself as a teenager. The students don’t know the meaning of the words now, but when in future they hear them used in context, the words and meanings will connect. Immersion enables deep language-learning by intuition. ‘Life is like the harp string. If it is strung too tight it won't play, if it is too loose it hangs. The tension that produces the beautiful sound lies in the middle.’ (Gautama Buddha) In World War 2, when faced with a critical decision on how to respond to the Nazi threat, one of Winston Churchill’s advisers argued forcefully that ‘organisation is the enemy of improvisation’. This wasn’t a diatribe against the power of organisation per se. It was, however, deeply rooted in a belief that the UK’s main chance of success would be to act in ways that would capitalise on its own agile cultural traits – and leave the highly-organised German war machine disorientated and defeated. I’ve noticed there are parallels in learning a second language too. Students are often taught in highly-organised ways – focusing on vocabulary, grammar, reading and writing. It can provide them with a useful foundation, yet can also leave them completely paralysed in free-flow conversation. I’ve concluded that, at least in this respect, ‘Accuracy is the enemy of fluency.’ Remove the expectation to get everything right, distract from fears of making a mistake, and the words will start to flow. That said, I need to beware of unhelpful polarisation. Early in my OD career, I worked alongside an experienced HR consultant, Chris Rowe, who introduced me to a tight-loose principle. I had argued instinctively that an organisation needed to let go of its highly-organised, stifling structures and processes to become more flexible, responsive and innovative. Chris challenged me: there is a time for tight and a time for loose – and wisdom in knowing which, where, when and for whom. ‘Diversity doesn’t look like anyone. It looks like everyone.’ (Karen Draper) An English guy from the UK in Germany… working alongside Mexican and Romanian English teachers to teach English to German students… whilst supporting a Liberian student to learn German… and alongside a German Mathematics teacher to introduce German students to Philippines language and culture... whilst supporting Iranian refugees with coaching. It’s an incredible privilege to be here. Every day brings new surprises. Today, I chatted with a German teacher… with an Arabic name... who sits quietly in the staff room yet spends her free time doing extreme caving and travelling to different countries around the world. I had another surprise when I shared some videos of Filipino jungle children, dancing, with two groups of German students. They spontaneously leapt up from their seats to join in. When I asked these students if any could speak another language, I was amazed by the range of their responses: Czech, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Russian, Turkish, Ukrainian. It reminded me of the power and potential of diversity, where young people see beyond national boundaries, see each other as individuals that transcend different languages and cultures, and are truly open to something, someone, new. ‘The art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery.’ (Mark Van Doren) This looks and feels so very different to my own school days. It has been fascinating to explore the spirit and approach to working with students at a Montessori school in Germany over the past few weeks. Laura, an English language teacher from Romania, sets out a creative range of different activities in a classroom. The children look around and choose whichever activity appeals most to them. Every activity involves doing something physical, not just thinking. I’m struck by how the teacher chooses to offer only minimal explanation. Each student works at their own level and pace and problem-solves for themselves, or with others, if they get stuck. The teacher is available – if needed. Kathrin, a maths teacher, invites the students to sit in a circle and introduces me, briefly. She invites the students to practise English by asking me questions directly, questions to which the answer must be a number. They ask, ‘How tall are you?’, ‘How much do you weigh?’, ‘What’s your shoe size?’, ‘What did your trainers cost?’ etc. We notice that the measures I use in the UK are different to those they use in Germany. This sparks curiosity and the students work out how to convert the numbers I give them into those that are meaningful for them. The teacher writes each number on a large sheet of paper, then uses those numbers as the basis for introducing a maths method for that day. Melina, also an English language teacher, from Mexico, works with those students who find learning difficult. She uses a creative range of short, energetic, and fast-paced techniques that capture and hold their attention. Again, I’m struck by the use of physicality in the activities she facilitates. She adopts an evocative elicitation-based stance, stimulating the students to lead the activities, to play an active role and to work out the answers for themselves. (I noticed my own temptation to step in if they got stuck and, paradoxically, how often they didn’t need my help – if I simply allowed them time and space to resolve their own challenges). I'm a student among students and I feel inspired. ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. 'Home isn't where you're from, it's where you find light when all grows dark.' (Pierce Brown) I was invited yesterday to meet with a family of asylum seekers who have recently arrived in Germany from Syria. They are living in temporary accommodation, a house with no furniture, only mattresses on the floor, yet at least in a place of safety until suitable accommodation is found. The three young children greeted us excitedly with wide grins when we arrived at the door. My hostess, Margitta, a Christian activist with a passion for the poor and most vulnerable, had brought a travel cot in preparation for the arrival of the family’s new baby. As we sat on the floor together, the father pointed to himself apologetically and said, ‘No German’, then to us, ‘No Arabic.’ At that moment, some simple words and phrases I had learned some 40 years ago whilst working briefly in a Palestinian hospital came tumbling into my mind. I felt unsure if I had remembered them correctly, and a bit nervous that my English-accented Arabic might sound a bit weird, but nevertheless spilled them out: ‘Hello, How are you? Fine thanks. Please. Thank you. Yes. No.’ Etc. At least that’s what I think I said. Not exactly the stuff of fluent conversation. Yet, in that moment, the whole family looked stunned…then absolutely delighted…then with huge smiles burst into a spontaneous applause. When arriving in an alien land where so much is so unfamiliar, to hear simple words spoken in one’s own language must feel like a reassuring familiarity, a comforting reminder of one’s own home. I sensed it mattered, too, that my own stumbling German made them feel less isolated, less alone. Small things can be big things. Our weakness can be our strength. ‘It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.’ (Henry David Thoreau) Psychologist Albert Ellis, widely regarded as the founding father of what has today evolved into Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, noticed that different people responded differently to what were, on the face of it, very similar situations. Previously, you might have heard, ‘Person X feels Y because Z happened’. It assumed a direct causal relationship between emotions and events. Ellis’ observations challenged this, proposing that something significant was missing in the equation. After all, if this assumption were true, we could expect that everyone should feel the same way in circumstance Z. Curious about this, Ellis concluded that the critical differentiating and influencing factor that lays between emotions and events is belief. It’s what we believe about the significance of an event that affects most how we feel in response to it. Here we have person A who hears news of a forthcoming redundancy with fear and trepidation. He believes it will have catastrophic financial consequences for himself and his family. Person B receives the news with positive excitement. She believes it will provide her with the opportunity she needs to pursue a new direction in her career. Drawing on this insight, organisational researchers Lee Bolman & Terrence Deal proposed that, in the workplace, what is most important may not be so much what happens per se, as what it means. The same change, for instance, could mean very different things to different people and groups, depending on the subconscious interpretive filters through which each perceives it. Such filters are created by a wide range of psychological, relational and cultural factors including: beliefs, values, experiences, hopes, fears and expectations. This begs an important question: how can we know? Hidden beliefs are often revealed implicitly in the language, metaphors and narratives that people use. To observe the latter in practice, notice who or what a person or group focuses their attention on and, conversely, who or what appears invisible to them. Listen carefully to how they construe a situation, themselves and others in relation to it. Inquire in a spirit of open exploration, ‘If we were to do X, what would it mean for you?’; ‘If we were to do X, what would you need?’ This is about listening, engagement and invitation. Attention to the human dimension can make all the difference. ‘It’s always best to pose a question, except when it isn’t.’ (Claire Pedrick) It reminds me of Ted Winship, a trade union activist I worked with as an apprentice. He often spoke like this: ‘It’s always the same, sometimes.’ It was a kind of word play that made people stop – and think. Or a teacher at school whose name, sadly, escapes me now: ‘If you have nothing to say, say it.’ It was some years before I finally worked out what she meant. I think too of Jesus. He often spoke in parables – stories, analogies, that left many of those who heard him feeling perplexed or bemused. Yet, why do it? In an era of endless soundbites, personal broadcasts, voices calling out loudly in all directions competing for air space, it’s hard to achieve cut-through. Even harder, perhaps, to achieve break-through; to have a meaningful influence or impact. We create and consume words like candy and in high volume, yet few provide the life-giving spiritual, mental and emotional sustenance we need to learn, develop and grow. How do you use language to evoke or provoke, reveal or inspire? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed