|

‘Leadership is influence.’ (John C. Maxwell) It’s one thing to have insight. It’s another thing to exert influence on the basis of that insight. This is often a dilemma for leaders and professionals when seeking to influence change across dynamic, complex systems and relationships. After all, what if I can see something important, something that could make a significant difference, yet I can’t gain access to key decision-makers? Or what if, even if I can get access, they’re not willing to listen? What if people are so preoccupied by other issues that my message is drowned out by louder voices and I can’t achieve cut-through? Early in my career, I worked as OD lead in an international non-governmental organisation that was about to embark on radical change. I’d studied OD at university on a masters’ degree course and, based on that experience, could foresee critical risks in what the leadership was planning to do. I tried hard to get access to raise the red flags but, by the time I met with the leaders, it was too late. They had already fired the starting gun on their chosen programme. My concerns turned out to be well-founded, and the changes almost wrecked the organisation. I agonised for some time over why I’d been so ineffective at influencing their decisions. I learned some valuable lessons. Firstly, the view I held of my role – the contribution I could bring – was different to that of the leaders. I viewed myself as consultant whereas they viewed me as service provider. Secondly, the leaders had become so emotionally-invested in the change they had designed that they reacted defensively if challenged. They saw my well-meaning red flags as resistance rather than as a genuine desire to help. I would need to change my approach. Since then, I have practised building human-professional relationships with leaders and other stakeholders from the earliest opportunity. These relationships are built on two critical factors: firstly, respect for e.g. the studies, training, expertise and lived experience they bring to the table; and, secondly, empathy for e.g. the responsibilities, hopes, demands and expectations they face – both inside and outside of work. Against this backdrop, I’m able to pray, share my own insights and, where needed, advocate a change from an intention and base of support.

12 Comments

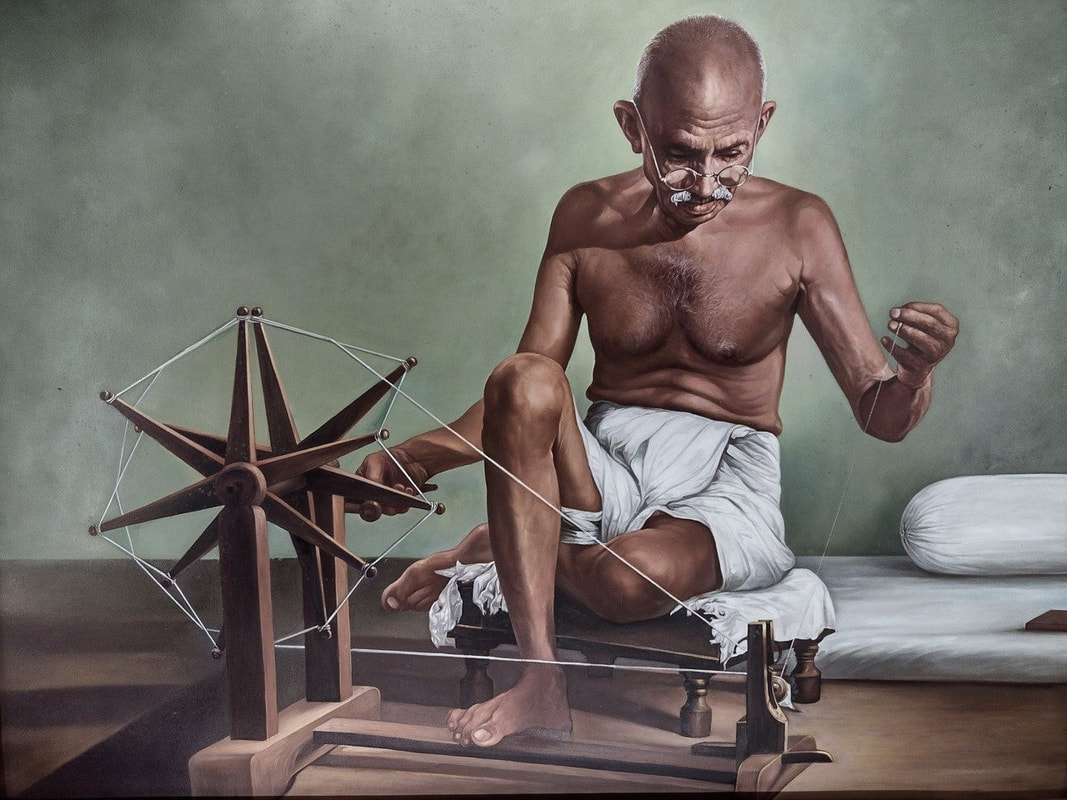

‘Curiosity killed the cat, but for a while I was the suspect.’ (Steven Wright) Action Learning facilitators sometimes feel anxious if there are prolonged periods of silence in a group, or if an individual is particularly quiet. They may assume, for instance, that the person is uninterested to engage with the group or the process. I had that experience once (online) where a participant sat throughout a round wearing headphones, nodding and swinging in his chair as if to music. When I asked if he had any questions, he clearly had no idea what the presenter had been talking about. I addressed this with him directly after the round, checked if there was anything he would need to be and feel more engaged, then agreed that he would leave the set. That said, there are a wide range of potential factors that may influence if and how a person engages in a set meeting and, at times, different reasons for the same participant during different rounds. I will list some of them here as possibilities: if a person has been sent to a set, rather than has chosen freely to join it; if there is formal or cultural hierarchy within the group; if there has been insufficient attention paid to agreeing ground-rules for psychological safety; if building relational understanding and trust has been neglected; if a person doesn’t like someone else in the group, or fears negative evaluation by others in the set; if a person lacks confidence. There are other possibilities too: if a person has an introverted preference and processes thoughts and feelings internally; if a person has a reflective personality and needs more time to think; if a person doesn’t feel competent with the language or jargon being used; if the person can’t think of a presenting issue or a question; if last time the person spoke up in a group meeting, it was a difficult experience or had negative consequences; if a person is preoccupied with issues or pressures outside of the meeting; if a person is distracted mentally or impacted emotionally by something that happened before the meeting, or is due to happen after it. So, what to do if a person is completely silent in a set? Here are some ideas, to be handled with sensitivity and, if appropriate, outside of the meeting: take a compassionate stance – there may be all kinds of reasons for the silence of which you are unaware; avoid making judgements – silence does not necessarily indicate disengagement; be curious – ask the person tentatively, without pressure, if any issues or questions are emerging for them; avoid making assumptions – ask the person what the silence means for them and if there’s anything they need; have an offline conversation with the person – if their silence persists for more than one meeting. ‘Always vote for principle, though you may vote alone.’ (John Quincy Adams) I never had the privilege of meeting Soji Taguchi, but I do wish I had. Soji was a manager at a Japanese-owned textiles factory in the Philippines. Seeing how meagrely the Filipino workers were paid, he gave away a significant portion of his own salary each month to top up theirs. When a young Filipina was severely distressed one day and, in her upset, damaged an expensive piece of machinery, he paid for the repairs himself. Instead of chastising her he listened to her plight and, subsequently, regularly slipped money (secretly) into her pockets to help her, a poor teenager, to pay her bills. This woman’s life is now a clear reflection of his. The power of a positive role-model. Ted Winship was my mentor, a shopfloor supervisor at an industrial site in the UK. Once, the workers refused to enter an enclosure because the conditions in it were so terrible. The manager told Ted that, if he could persuade them to do the work, they would all be paid a substantial bonus. Ted took the manager at his word. He entered the compound first and the work was completed on time. At the end of the project, however, the manager refused to pay the bonus and only gave Ted his. It was a serious breach of trust. On hearing of this betrayal, Ted confronted the manager but to no avail. He distributed his own bonus to the workers, resigned from his job and walked out. Ethics in action. Self-sacrifice for the sake of others. The personal costs were high – but the spiritual benefits were immeasurable. ‘If you’re not confused, you’re not paying attention.’ (Tom Peters) Leaders who develop strategy collaboratively with diverse key stakeholders often find that inviting others in proves critical to its success. It recognises that no leader, no matter how knowledgeable or experienced, can know everything and it values the contribution that others can bring. That said, leaders can also feel overwhelmed if levels of participation are high and inputs are complex. These tips (below) are, therefore, designed to help leaders sift through and make sense of the reams of hopes, ideas, information, impressions, data etc. that they may surface and receive through strategy research and through inviting input from various people and groups. They are not intended as a prescriptive one-size-fits-all set of rules. Have a glance and see which, if any, work best for you. 1. Don’t panic In the midst of some great information and ideas, you are also likely to receive input that will look unclear, confusing or contradictory. There may be handwriting you can’t read, comments in shorthand that made sense to the person who wrote them but don’t make sense to you etc. You may receive so much input from diverse people and sources that it could feel bewildering. If so...don’t panic! 2. Research questions Go back to your research questions. Use them as a guide to sift through the input you have received. How far does the overall input contribute to answering the questions you set out to address? Has any of it raised wider or deeper questions that need to be acknowledged? Is any of the input interesting but distracting? Avoid the temptation to race down fascinating rabbit holes that take you off track. 3. Test a hypothesis Some leaders suggest formulating a hypothesis – a provisional answer to the questions you set out to answer – before sifting through responses. This provides a focus, a testing stone, and enables you to check each response: ‘Does this support or contradict the hypothesis?’ If it doesn’t relate to the hypothesis, shelve it for now so that you don’t get distracted. You can always circle back to it later. 4. Cluster responses Some leaders prefer to start with a blank sheet, skim through responses and note intuitively what core themes or ideas emerge. You can then place responses under those themes, adding or modifying themes as the sifting process progresses. Don’t worry about identifying the themes perfectly too early. You can always hone them and see what answers they point towards later. 5. Test your biases It can be tricky for leaders to look at responses afresh, especially if we have a strong interest in the work we do currently or strong views about how we should move forward. During the research phase, I refer to these challenges as ‘blind spots’ (assumptions) and ‘hot spots’ (sensitive areas). Invite others to test your assumptions and to point out if you appear to avoid challenges or new ideas. 6. Trust the process We may have invited and received input from a diverse range of people and groups. Whilst no strategy research will ever be 100% exhaustive and conclusive, the insights that we draw through a collaborative strategy venture will in most cases be good enough – that is, good and enough as a signpost to the future. Pray, be confident in what you know and excited by what you discover! ‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life? ‘We don’t have a plane crash scheduled for today, but I thought I’d take you through the emergency procedures just in case.’ (KLM Air Hostess) I love the difference that a sense of humour can make. The air hostess (above) made everyone laugh during the passenger safety briefing on a return flight from the Netherlands today. The airline’s own plane had experienced maintenance problems so it had had to borrow one from another airline. One hostess complained, with a glint in her eye, that the green décor didn't match the blue colour of her uniform. The passengers all laughed when another hostess made an announcement too, aiming to draw our attention to an apparent information light on the plane…only to correct herself moments later with, ‘Oh – this plane doesn’t have one!’ Brilliant. It took the terror out of the turbulence. On a more serious note, I had been in the Netherlands to work with a diverse NGO leadership team, to support its desire to enhance its international teamwork. I referenced briefly a couple of places in the Bible where the writer comments on the amazing potential of human diversity – where the Divine whole is seen, known and experienced to be more than the sum of its parts – yet also hints at the corresponding dark risks of undervaluing, fragmentation and conflict if not. Strikingly, the writer moves on in both places to emphasise a deep need for authentic love as the critical success factor. This insight set a spiritual-existential tone for the day, as we reflected on team-as-relationships. Returning to the plane – but this time as a metaphor, a participant from South Africa asked, ‘How many separate parts is a Boeing 747 aircraft made up of?’ Apparently, the answer is about 6,000,000. ‘And what do these diverse components all have in common?’ Puzzled faces all round now. ‘None of them can fly.’ I thought this was genius. What a great way to dispel the myth of the all-sufficient self in the face of the dynamic complexities of teams, organisations and wider world. We worked through an Appreciative Inquiry next, drawing on positives of the past and aspirations of the present to co-create shared trust and vision for the future. Set the trajectory. Fasten seatbelts. Enjoy the flight. ‘You could start a fight in an empty room, mate.’ (Allan Jones) I’ve never sought conflict. Far from it. I much prefer harmony and peace. That said, however, I can’t escape a similar calling to that which Martin Luther King once heard: ‘Stand up for righteousness! Stand up for justice! Stand up for truth!’ It’s a call that burns deeply inside of me and has done, as far as I can remember it, for my entire life. I’m pained to admit that I haven’t always followed that voice anywhere near as courageously as MLK. I haven’t always handled it with his astonishing humility and love. I’ve stayed silent when I should have spoken up or spoken up when I should have stayed silent. My words have stumbled out clumsily. I’ve caused pain where I meant to bring healing and hope. Yet, at times, this vocational stance has proved authentic, valuable and worthwhile. In my 30s, I worked for a large UK charity in the health and social care sector. As an idealistic young radical, I challenged the leadership team on numerous occasions when I believed we were compromising our values. I tried to do this with prayer and humility and out of a genuine desire to build relationship and trust. On one occasion, the leadership team decided, in view of limited budget, to increase only senior leadership salaries until it had secured sufficient funding to increase frontline staff salaries too. I argued vociferously that we should do the exact opposite – and to freeze my own salary as a first step. On another occasion, the leadership team decided to reserve all spaces in its small head office car park for executives only, given that they didn’t have time to drive around to look for parking places elsewhere. I advocated passionately that, especially in the winter months, the spaces should be reserved for female and other vulnerable staff or visitors so that they wouldn’t have to walk along dark city streets at night to their cars. On yet another occasion, the leadership team recruited a ‘hatchet man’ on temporary contract to implement a tough restructure with associated redundancies. I protested that this blunt way of approaching the change would damage relationships, engagement and trust. At times, I imagined my challenges and counter-proposals were met with deafening silence or heavy sighs – especially as I wasn’t a senior leader at the time. Nevertheless, when a serious crisis broke out between the leadership team and entire middle management, both sides to the conflict invited me to mediate as ‘the only person they could trust’. The chief executive, a man of remarkable humility, took me into his confidence and treated me like a respected thought-partner. When I moved on, the company secretary wrote to me to say he had never encountered such integrity. Even the dreaded ‘hatchet man’ wrote that he wouldn’t hesitate to employ me alongside him in any future role. Pray with humility – take a stance – speak the truth in love. ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I — I took the one less travelled by.’ (Robert Frost) It was in a dark, cigarette smoke-filled pub one night. The trade union reps sat behind a long wooden table, cluttered with half-full beer glasses. We about-to-graduate apprentices sat opposite, waiting to be called forward. (It was in the days of closed shop when qualified trades people could only be employed if they held union membership). At the time, I supported the value of trade unions in principle, yet felt dismayed and disillusioned by the corruption that this source of power had created. I noticed my colleagues often lived in fear of the union rather than represented by it. If you said or did something that challenged or upset union leaders, you risked losing your union card and therefore your job. One by one, my fellow apprentices stepped up to the table. ‘Raise your right hand. Do you swear to abide by the rules of the trade union?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘OK, go and sit down.' My turn came. ‘Do you swear…?’ ‘No’, I replied. ‘I have no idea what the rules of the trade union are.’ The panel looked bemused. ‘You really want to read the whole rule book before you agree?’ ‘Yes’, I replied. The shop steward thrust a copy into my hands then ejected me forcefully from the meeting. ‘Wait outside until we call you back in.’ I skimmed through the book then, on return, insisted I was exempted from default political party contributions, as was my right according to the rules. They looked intensely frustrated but had to consent. I don’t think such encounters changed the trade union, but they did change me. Some months later, I was sent on a 2-week residential apprentices' programme that aimed to stimulate personal leadership qualities. I challenged the senior managers there with whom, providentially, I had opportunity to speak. ‘Why invest in this programme when the prevailing management behaviour in the workplace is so autocratic? We need to change culture, not just individuals’. They looked deeply uncomfortable yet I held my ground. (They had, after all, encouraged personal leadership). At the formal dinner of the final evening, they invited me to sit at the top table alongside the most senior leader for that region. I was learning to navigate my way through power structures and systems and to exercise personal and political agency. [See also: Pivotal points] ‘Open-ended questions can help clients reflect and generate knowledge of which they may have previously been unaware.’ (Jeremy Sutton) You may have noticed when you order or buy something that, before asking you for payment, the salesperson may ask, ‘Anything else?’ It’s a simple prompt that, when posed, may cause you to remember something, or to make a choice vis a vis something over which you had been wavering. This same approach can be useful in coaching. A coach could ask during the contracting stage: ‘Is there anything else we should be talking about?’ It can sometimes reveal a very significant issue that, until invited, feels unclear to the client, lays out of conscious awareness or has not yet been aired. In action learning, similarly when a facilitator invites a presenter to say something more about the issue they would like to think through, insights that come to mind or actions they plan to take, they can ask, ‘Anything else?’ A presenter, when prompted, will often respond with: ‘Oh yes, and…X’ So, now for a brief moment of reflection. What ideas come to mind for you now as you read this blog? Jot down those that surface immediately… then pause for a moment before moving on to something else in your busy schedule. Ask yourself: ‘Anything else?’ and see what may emerge. ‘Behind every problem, there is a question trying to ask itself. Behind every question, there is an answer trying to reveal itself.’ (Michael Beckwith) Second-guessing. It creates all sorts of risks. ‘What time does Paul’s meeting finish?’ Is that a simple request for information, or is there a question behind the question? ‘I’d like to meet with Paul this afternoon. What time will he be free?’ That’s better. ‘I need you to present an urgent strategy update to the Board.’ Again, is that a simple instruction, or is there an issue that lays behind it? ‘I’d like to demonstrate to the Board next week that our investments are achieving the desired results.’ Better. A problem with a question that fails to reveal the question, the issue, that lays behind the question is that it leaves the other party to fill in the gaps. In doing so, they are likely to draw on their own assumptions – which could be very different to your own – or sometimes their anxieties. ‘Is he complaining that Paul’s meeting is over-running?’ ‘Is she inferring there’s a problem with my work on strategy delivery that I hadn’t been aware of?’ Simply stating our intention can make all the difference. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed