|

‘We're fascinated by the words – but where we meet is in the silence behind them.’ (Ram Dass) I remember my first experience of haggling over the price of a leather belt in a Palestinian marketplace. I was a teenager at the time and I found this approach to buying and selling novel and entertaining. The smiling street vendor played the game skilfully. I asked, ‘How much?’ to which he responded, '$6.’ ’$6?’ I replied, ‘I could get the same belt at another stall for $1. How about $2?’ ‘$2?’ He replied, ‘Please don’t insult me. It cost me more than that to make it. As a special deal, however, I’ll give it to you for $5.’ ‘$5?’ I replied, ‘The most I would pay for it is $4.’ ‘$4?’ He replied. ‘Don’t you realise I have a family and children to feed?!’ He grinned. We closed at $3. To a Westerner, where buying and selling is typically more transactional than relational, this toing and froing can feel like a manipulative game; frustrating, bordering on dishonest and time-wasting. That’s mostly because we tend to miss the underlying cultural meaning and purpose to this type of engagement. I met recently with an international team from USA, Netherlands, Jordan and South Africa. They are part of a Christian organisation and were keen to identify and work through some cross-cultural and relational challenges. I decided to share a short passage from the Bible with them, then to invite them to discuss what sense they made of it: “Jesus withdrew to the region of Tyre and Sidon. A Canaanite woman from that vicinity came to him, crying out, ‘Lord, Son of David, have mercy on me! My daughter is demon-possessed and suffering terribly.’ Jesus did not answer a word. So, his disciples came to him and urged him, ‘Send her away, for she keeps crying out after us.’ He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.’ The woman came and knelt before him. ‘Lord, help me!’ she said. He replied, ‘It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.’ ‘Yes it is, Lord,’ she said. ‘Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.” And now to the critical closing: “Then Jesus said to her, ‘Woman, you have great faith! Your request is granted.’ And her daughter was healed at that moment.” (Matthew 15:21-28) To the Westerner who views language and transactions in literal, linear, straight lines, Jesus’ initial responses to the woman are shocking. We take his opening action as his definitive stance. We don’t see the smile on his face or the glint in his eye, or understand the movement as the interaction progresses. We may assume the story is written to affirm the woman’s perseverance. We may think she has changed his mind. We are likely to miss the Semitic ritual of building or navigating a relationship. The Jordanian participant saw this immediately. The others looked surprised. (I must confess I didn’t understand this, too, until a Kurdish-Iranian friend had explained this dynamic to me). The cross-cultural implications are clear. If I judge your actions by unknowingly mis-inferring your intentions (being influenced subconsciously by my own cultural assumptions), all kinds of misunderstandings and tensions can arise. It cautions me-us to approach people and groups from different cultures with an open mind, a spirit of curiosity and a great deal of humility. Bottom line: We’re not only negotiating a price; we’re also negotiating a relationship.

18 Comments

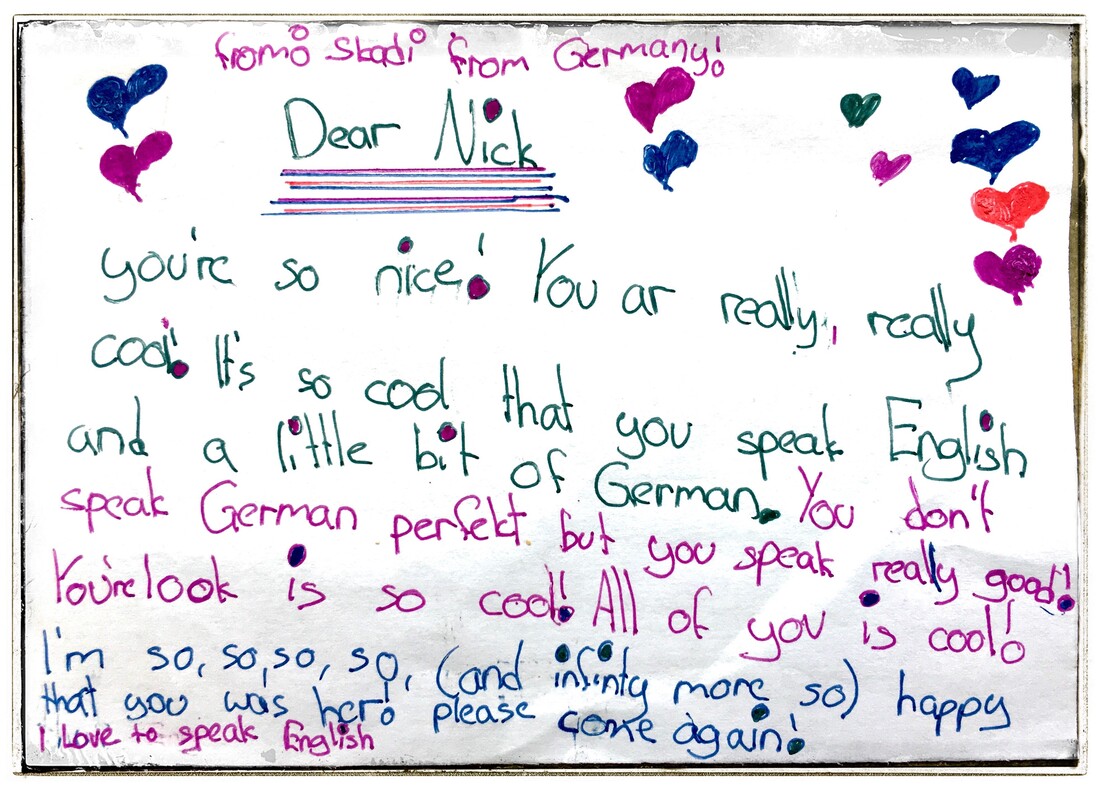

‘Well-behaved women rarely make history.’ (Laurel Thatcher Ulrich) International Women’s Day. A day to recognise and celebrate the extraordinary contribution of women all over this world and throughout all history. There are so many amazing women who have inspired, stretched and enriched my life: those I’ve known, those I’ve heard or read about and those I’ve only encountered indirectly through the personal-cultural legacy they’ve left behind. This is a shout-out, a thank you, to all women – especially to those who are and feel invisible and unseen; those who live on the frayed and torn edges of societies; those who persevere in the face of poverty, vulnerability and other threats; those who live and love in a way that goes unnoticed and unknown. You humble and challenge me. The world is a better place because you're here. ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.’ (Margaret Mead) ‘520,000,000,000’. I wrote the number slowly…and…deliberately across the whiteboard at the front of the class. The students looked on, intrigued. I asked, ‘Who can guess what this number means?’ The playful ones quickly put their hands up: ‘The population of the world?’ ‘The distance to the moon?’ I responded, ‘The number of Pesos (= US $8 billion) that people across the world spend on skin-whitening products in one year.’ The room was filled with looks and sounds of astonishment now. The students had considered this as a private personal-relational issue rather than a global economic one. This was part of a 3-day workshop for student teachers and social workers – that is, key influencers for the future – in the Philippines. The first time I had arrived in the country, I had been naively taken aback when one of the people who greeted me apologised for their skin colour. My Filipina co-facilitator explained that this is a common phenomenon, where people evaluate themselves and are evaluated by others for how dark or light their skin is. The students went on to share heart-breaking personal testimonies of how far this has impacted their lives, prospects and sense of worth. They were very surprised to hear how much money, by contrast, people in wealthy countries spend on products, treatments and trips abroad to darken their skin. I took some skin-tanning lotion with me from the UK to show them – and they could hardly believe their eyes. We went on to consider the deep cultural drivers and diverse vested interests that lay behind the skin-whitening industry. The lively debate that ensued generated novel campaign ideas to address stakeholders (e.g. manufacturers; marketers; retailers; consumers), and its damaging spiritual, psychosocial and financial effects. ‘Our reality is narrow, confined, and fleeting. Whatever we think is important right now, in our mundane lives, will no longer be important against a grander sense of time and place.’ (Liu Cixin) I think you could say we’re a family with an international outlook. My parents travelled extensively around the world and have touched most continents. My older brother lived in Brunei, married a Malaysian woman and has visited almost every country in Asia. My sister lived in Germany, mixes with friends from different countries and travels frequently to Spain to do salsa dancing. My younger brother ran a charity for and in Romania, did a medical mission in remote areas of the Amazon jungle and works in Dubai. I’ve been interested in different languages and cultures from childhood, have worked in 15 countries and have visited, have friends in and have worked with people from a lot more. I watch almost exclusively international news, pay special attention to South-East Asia and my home is adorned with globes and colourful maps. Much of my life has been preoccupied with the Nazis and how to use my own life to help avoid anything like such horrific atrocities ever happening again. Against this backdrop, my own coach, Sue, posed two interesting challenges recently: ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – overseas with the poor and vulnerable in far-flung places yet to be, physically, here in the UK?’ and, ‘What’s it like to spend so much of your life – mentally, emotionally and spiritually – in World War 2 yet to be, physically, here and now?’ What great questions. They resonate profoundly, for me, with what it is to be a follower of Jesus – a deep dissonance that arises from being in this world, yet in some mysterious way being not of this world. Existentially, it’s a kind of dislocation that, a bit like for Third Culture Kids (TCK), creates a sense of being a child of everywhere yet, somehow, not a child of anywhere – at least in this lifetime. I often feel more at home when I’m away from home, a paradoxical dynamic that both draws and propels me into different times and places and to seek out God, diversity and change. It means being a traveller, not a settler, and has influenced every facet of my entire life, work and relationships. 'There is no act too small, no act too bold. The history of social change is the history of millions of actions, small and large, coming together at critical points to create a power that governments cannot suppress.' (Howard Zinn) At the heart of coaching generally lays a desire and opportunity for impact and change, a goal that may seem obvious, but one that raises important questions. As coaches aspiring to make a difference in the world, we can find ourselves navigating complex dilemmas. When we work with agents of change in, say, NGOs, charities, churches or public sector organizations, we often seek to empower individuals, teams, and organizations to be resourceful and effective in achieving transformation. One challenge we may encounter is determining the coaching agenda. A Western coaching ethic advocates for giving the client complete control over the agenda, focusing on their chosen goals and boundaries. While this approach seems straightforward, our intention of promoting social change may lead us to contemplate how much influence we should exert on the client’s journey. What if the client's solutions seem unethical, ineffective, or could pose risks to broader social development? Furthermore, when working in diverse cultural contexts, we need to be mindful of differing perspectives on individual autonomy. In some Eastern and Southern cultures, the concept of setting individual goals might not resonate the same way it does in the West. People in these cultures often prioritize the wishes and expectations of a wider group, whether family, team or community, before their own hopes and ambitions. We could risk inadvertently imposing our own cultural values onto the client. The solution often lays in recognizing the significance of context and building a strong and trusting relationship with the client. By understanding the dynamics of power, language and agendas that may emerge between us, we can gain insight into the issues at hand and potential solutions. We become allies, working together to achieve meaningful impact. A critically-reflective process allows us to adapt our coaching practice on route and to challenge our assumptions as we learn and grow. ‘When trouble arises and things look bad, there is always one individual who perceives a solution and is willing to take command. Very often, that person is crazy.’ (Dave Barry) We can think of leadership as the property of a structure, in which a person designated as a 'leader' holds particular responsibilities and has, at least in principle, the hierarchical authority needed to fulfil them. We can also think of leadership as an intrinsic property of an individual. In this sense, leadership is something that resides within and emanates from a person, something that she or he has and does. This is the realm of competency frameworks and of leader-development initiatives. We can also think of leadership as the property of a group; for instance, a leadership team. In this idea, shared leadership is something exercised by a collective, where a diverse united group is, in potential, more than the sum of its parts. We can also think of leadership as a property of a dynamically-complex eco-system, in which acts of leadership emerge, sometimes unexpectedly and from unexpected places, and exert influence. This is the arena of dispersed and distributed leadership. In organisations, I’m finding the latter perspective especially useful. When working with leadership teams, I invite participants to reflect on the eco-system (cf Gestalt: field) as a whole; for instance: 'Where is leadership-as-influence exercised, inside or outside of the organisation’s boundaries? What are the distinctive roles and responsibilities of different 'leadership' entities within the system? What are the relationships between them? What does each need from the others to be effective?' I notice this invariably opens up far deeper, wider and richer conversations than those that focus on individual leaders alone, or leadership teams in isolation, as if they exist in a cultural-contextual vacuum. Some people find it useful to experiment with mapping their eco-system graphically, recognising that any depiction will reveal and, therefore, create opportunity to open up to healthy exploration and challenge, the way in which they construe their reality and leadership dynamics within it. ‘We build too many walls and not enough bridges.’ (Isaac Newton) Travelling 33 kilometres from Münchberg in former West Germany to Mödlareuth at the edge of the former East, yesterday, felt like travelling 33 years back in time. The first occasion on which I had visited the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR) was shortly after the infamous Berlin wall came down, and before the subsequent German reunification that confined the now-defunkt DDR to the history books. I was struck, then, by how colourful it was in the East, in contrast to the documentaries we saw on TV where it was almost invariably depicted in shades of drab grey, black and white. The next thing that struck me was how naïve I had been to imagine the East was really like that. Unlike most state boundaries around the world, the DDR’s border with its ominous walls, fences, watch towers, searchlights, minefields and patrols with dogs and guns at that time were designed primarily to keep the DDR’s own citizens in, rather than – like a former US President’s vision of his own big wall – to keep other people out. According to the Netflix documentary ‘Merkel’ (2022), former German Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel’s upbringing in and experience of living behind the DDR’s stretch of the iron curtain had a significant psychological influence on her resistance to hard borders in and around the European Union. The past has a way of playing itself out in the present. The parts of the East that I visited this week looked remarkably similar to how they did all those years ago. The physical border is gone, except in those places where remnants have been preserved to retain a sense of history-as-real and to educate intrigued visitors and tourists. The ongoing cultural differences and economic disparities between West and East, however, continue to have a marked influence on German politics. The pale-painted houses still look now as they did as before, some like symbols of a distant, decaying past that lost and never quite managed to recover and regain their former glory. The new cold war, gaining in foreboding heat, carries a disturbing resonance. ‘Diversity doesn’t look like anyone. It looks like everyone.’ (Karen Draper) An English guy from the UK in Germany… working alongside Mexican and Romanian English teachers to teach English to German students… whilst supporting a Liberian student to learn German… and alongside a German Mathematics teacher to introduce German students to Philippines language and culture... whilst supporting Iranian refugees with coaching. It’s an incredible privilege to be here. Every day brings new surprises. Today, I chatted with a German teacher… with an Arabic name... who sits quietly in the staff room yet spends her free time doing extreme caving and travelling to different countries around the world. I had another surprise when I shared some videos of Filipino jungle children, dancing, with two groups of German students. They spontaneously leapt up from their seats to join in. When I asked these students if any could speak another language, I was amazed by the range of their responses: Czech, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Russian, Turkish, Ukrainian. It reminded me of the power and potential of diversity, where young people see beyond national boundaries, see each other as individuals that transcend different languages and cultures, and are truly open to something, someone, new. ‘One fish asks another fish ‘How is the water?’ The two swim on for a bit and eventually the other fish replies, ‘What is water?’’ (David Foster Wallace) The more I know, the less I understand. That’s the conclusion I came to after spending 5 years in a Christian faith community in London with 70% Nigerian people, 20% Ghanaian, 8% Mauritian and 2% from the UK. It’s a belief that’s been reinforced by 7 years closely alongside people from the Philippines and other countries in East and South East Asia. Beyond surface-level cultural traits such as distinctive clothing and food, culture runs very deep, mostly well below the radar of conscious awareness. Like the values and beliefs that underpin it, culture often only becomes known, including to ourselves, when we encounter a person or situation that contradicts or clashes with it. It can take us by surprise. I’ve made various cross-cultural blunders on route, ranging from an innocent hug in one context to posing questions in a group in another. On reflection, I’ve sometimes been astounded by my own naivety. Yet few opportunities for learning compare with a cross-cultural experience. It may feel like a bumpy ride on route yet the results can be transformational. [See also: Cross-cultural coaching; Crossing cultures; Cross-cultural action learning] ‘You always have two worlds. The one you are in now right now and the one beyond your world.’ (Mehmet Murat Ildan) This was such a heart-warming experience. I met with a class of 10 year-olds at a Montessori school in Germany this morning. They had invited me to share some of my experiences in the Philippines. I wondered how I could help to bridge the cultural and contextual gaps for them, to enable them to sense a feeling of connection with children of a similar age in a different world, rather than seeing children from a jungle village as totally alien. I opened by posing questions to the class about their own experiences of visiting different places, different countries with different languages etc. I asked who, if any, can speak a second language and was amazed by the diversity of second languages in the group. I showed them a world map, then a map of the Philippines, then taught them some simple phrases I had learned there. They loved practising these words in a different language. I showed them photos and short video clips from the Philippines – school children, motorbikes with sidecars, wooden houses, travelling on a boat through the jungle, children playing games, village children teaching me their local dialect (with lots of laughter), children performing the most amazing dance routines etc. I invited the class to practise one of the fun games they saw the jungle children playing on video. They leapt at the chance. At the close of the class, they asked me excitedly to take them with me, if I were ever to return to the Philippines. I was heartened by their ability to imagine themselves, and people, in a different world, so easily and so vividly. One child handed me a hand-written note, and a small group came forward to ask if they could give me a hug before I left. I feel humbled and inspired by these children – and by the Filipino jungle children who made this possible. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed