|

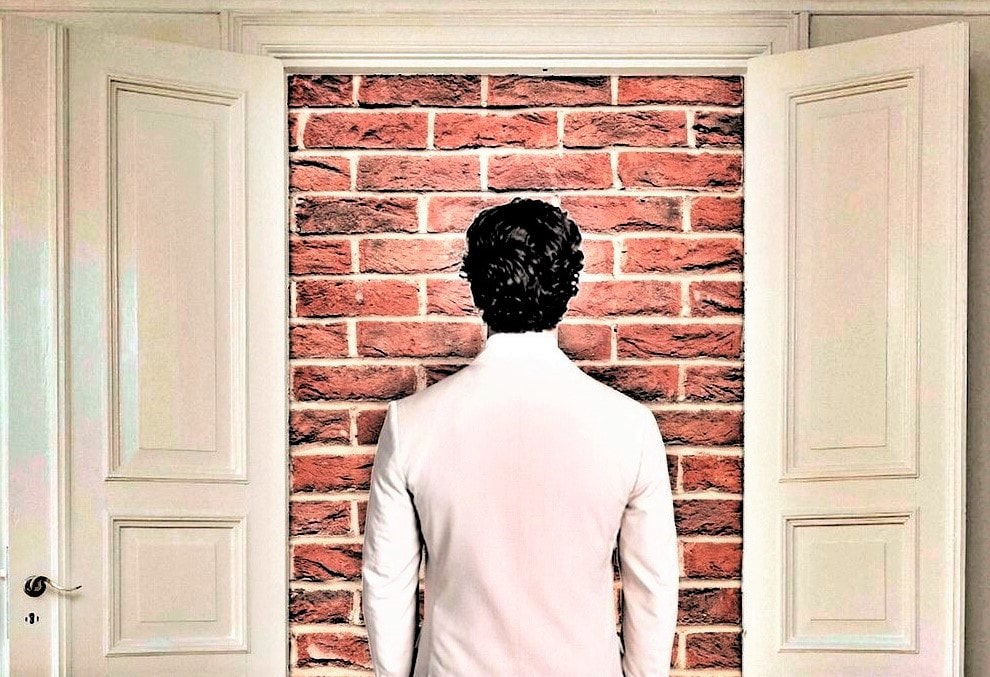

‘Good endings make sense, evoke emotions like contentment, anger, sadness, or curiosity, shift the person’s perspective or open her mind to new ideas. Good endings bring the person to some kind of destination.’ (Alex J Coyne) Lilin Lim, my sister-in-law, reads the back page of a novel first to decide whether it looks like the story is worth reading. There’s something about a good ending that can make whatever went before it feel worthwhile – the time, effort or, at times, struggle to get there. Think back to your own life and work peak experiences: e.g. birth of a child, achievement of a desired promotion or qualification, overcoming of a disability or fulfilment of a dream that, perhaps, felt hard at the time yet worked out well in the end. Conversely, think back to seminars, workshops or meetings you have taken part in that didn’t result in anything remotely meaningful to justify the investment. Academic Peter Cotterell commented satirically that, similarly, many lectures and articles can feel like, ‘a plane in the sky that takes off well yet finds itself circling in the clouds and can’t find a way to land.’ Stephen Covey said, ‘Begin with the end in mind’, a perspective that resonates well with the biblical idea of an end-revelation to draw us forward. This same principle applies in coaching and action learning. If we open a conversation with questions such as, ‘In relation to X, where do you want to be an hour from now?’ or ‘Of all the things we could spend the next hour doing together, what, for you, would make this time well spent?’, it can help ensure an explicit sense of focus and purpose from the outset – and raise into critical awareness Gary Rolfe’s movement towards an ending: the ‘Now what?’, before considering the ‘What?’ and the ‘So what?’ David Clutterbuck suggests ending this type of conversation with an invitation to the client to reflect and summarise for him- or herself, using a simple 4xI framework: ‘What are the Issues we’ve talked about; what are the Insights that you’ve had; what are the Ideas that we’ve generated; what are your Intentions now?’ It’s a consolidating technique that can enable a sense of learning and closure for the client and a transition into action. It helps to avoid the risk of a session simply...fizzling...out. Rosie Nice poses useful grounding questions: ‘Are there any other dimensions you would like to explore before moving into actions? Would it be helpful if we were to consider some questions to help you think through what actions you might take? What’s the main thing you are taking away, having had opportunity to think this through?’ Sue Murkin ends with: ‘Given what you know now, how will this impact on your work? How could you see yourself using this? What will you do now?’ How do you avoid perpetual drift or an abrupt crash landing? How do you create a good ending?

17 Comments

Do your conversations ever feel dull, pedestrian? Do you find yourselves reaching agreement quickly but sense there’s a lack of inspiration, depth or stretch to what you’ve decided? There’s an idea in Gestalt coaching that involves experimenting with polarities. When exploring an issue or when people can’t think of useful options, try introducing opposite extremes.

I met with a leadership team this morning to look at talent management. Rather than opening with a proposal, a colleague and I sat at opposite ends of the table and role played a conversation in which each of us argued passionately for radically contrasting approaches. We invited the team to listen, to feel, to see what it evoked for as we played out the different scenarios. Claire Pedrick uses a technique that involves opening the arms out wide to signify a polarity. ‘Let’s imagine this extreme (looking to one hand) involves doing nothing. Let’s imagine this extreme (looking at the other hand) is the ‘nuclear option’. What would the nuclear option involve doing in practice? Now let’s explore other options that lie in the space between.’ I sometimes use a polarities technique in leadership workshops. For example, if exploring directive vs non-directive approaches, I may walk an imaginary line across the room and explain at each end what that extreme represents. I then invite the group to stand along the line. ‘Where do you find yourself most of the time?’, ‘Where you would like to be?’ When using physicality like this, it can be very powerful to ‘do it’ rather than ‘imagine it’. So, if the group is standing along a line as above, I will invite them to move physically to where they want to be, rather than just talk about it. Then, ‘How are you feeling as you stand there?’, ‘What do you notice about where others are standing?’, ‘Have a conversation – where you are now.’ Another polarity technique is great for exploring the merits and risks of a proposal. Using a flipchart, I will start by inviting the group to brainstorm all the positive benefits. I will then use another flipchart and invite the group to brainstorm all the reasons why it won’t work. I use a final chart to brainstorm, ‘So, in light of that…what would it take to make it work?’ The benefits of polarising in ways such as these can include: stretching the imagination, discovering new/radical ideas, surfacing diverse views and feelings, experimenting with courage, testing different experiences and approaches, releasing fresh insight and energy. If you have worked with polarities, I’d love to hear from you. What did you do? What happened? When did you last have a great conversation at work? I’ve noticed that frustration and fatigue often arise from conversations and meetings that lack focus, that feel pointless, that lack purpose. It’s one of the main reasons why there is so much cynicism about meetings in organisations.

Now while different types of conversation are appropriate for different relationships and situations, questions that tease out purpose can be very powerful. They surface assumptions and create opportunity to discuss and agree on what would be worthwhile. Here are some purpose-focused questions: Why are we here? What are we here to do? What would make this time useful? What is the goal we’re trying to achieve? What would a great outcome look and feel like? What do we want to be different by the end of this conversation? We can use purpose-focused questions at the start of a meeting or mid-way through if we start to notice drift or confusion. ‘Let’s just remind ourselves what we’re here to do…where we’re trying to get to.’ Focusing and re-focusing can energise our conversations and achieve great results. When teams are under pressure, e.g. dealing with critical issues, sensitive topics or working to tight deadlines, tensions can emerge that lead to conversations getting stuck. Stuck-ness between two or more people most commonly occurs when at least one party’s underlying needs are not being met, or a goal that is important to them feels blocked.

The most obvious signs or stuck-ness are conversations that feel deadlocked, ping-pong back and forth without making progress or go round and round in circles. Both parties may state and restate their views or positions, wishing the other would really hear. If unresolved, responses may include anger/frustration (fight) or disengagement/withdrawal (flight). If such situations occur, a simple four step process can make a positive difference, releasing the stuck-ness to move things forward. It can feel hard to do in practice, however, if caught up in the drama and the tense feelings that ensue! I’ve found that jotting down questions as an aide memoire can help, especially if stuck-ness is a repeating pattern. 1. Observation. (‘What’s going on?’). This stage involves metaphorically (or literally) stepping back from the interaction to notice and comment non-judgementally on what’s happening. E.g. ‘We’re both stating our positions but seem a bit stuck’. ‘We seem to be talking at cross purposes.’ 2. Awareness. (‘What’s going on for me?’). This stage involves tuning into my own experience, owning and articulating it, without projecting onto the other person. E.g. ‘I feel frustrated’. ‘I’m starting to feel defensive.’ ‘I’m struggling to understand where you are coming from.’ ‘I’m feeling unheard.’ 3. Inquiry. (‘What’s going on for you?’). This stage involves inquiring of the other person in an open spirit, with a genuine, empathetic, desire to hear. E.g. ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘What are you wanting that you are not receiving?’ ‘What’s important to you in this?’ ‘What do you want me to hear?’ 4. Action. ('What will move us forward?’) This stage involves making requests or suggestions that will help move the conversation forward together. E.g. ‘This is where I would like to get to…’ ‘It would help me if you would be willing to…’. ‘What do you need from me?’ ‘How about if we try…’ Shifting the focus of a conversation from content to dynamics in this way can create opportunity to surface different felt priorities, perspectives or experiences that otherwise remain hidden. It can allow a breathing space, an opportunity to re-establish contact with each other. It can build understanding, develop trust and accelerate the process of achieving results. It was an energising experience, facilitating a group of leaders this week who are keen to build a new high performing team. We pushed the boundaries of normal ways of working to stimulate innovative ideas in all aspects of the team’s work. We used photos to create an agenda and physically enacted people’s aspirations to avoid falling into conventional patterns of heady, rational conversation. It felt very different to meeting ‘because that’s what we do’. There was a different dynamic, energy and momentum. Participants leaned actively into the conversation, not leaning back in passivity or boredom. Yet it can be a real challenge to break free from tradition, from norms that trap a team in ways of doing things that feel familiar and safe but, deep down, lack inspiration or effectiveness. In our meetings, how often do we pause before diving into the agenda to ask, ‘What’s the most important thing we should be focusing on?’, ‘How are we feeling about this?’, ‘What is distracting us or holding our attention?’, ‘What could be the most creative and inspiring way to approach this?’, ‘What do we each need, here and now, to bring our best to this?’, ‘What would be a great result?’ So I presented a simple model to the team with four words: content (what), process (how) and relationship (who) encircled around goal (where). In all my experience of working with individuals and teams, whether in coaching, training or facilitation, whether in the UK or overseas, these four factors are key recurring themes that make a very real difference. They seem to be important factors that, if we get them right, make a positive impact. They lead to people feeling energised, more alive, more motivated and engaged. Conversely, if we get them wrong, they leave people frustrated, drained of energy, bored or disengaged. Worse still, if left unaddressed, they can lead to negative, destructive conflict that completely debilitates a team. We can use a simple appreciative inquiry to reflect on this.‘Think back to your best experience of working with another person or team. How did you feel at the time?’, ‘Think back to a specific example of when you felt like that with the person or team. Where were you at the time? What were you doing? What were they doing? What made the biggest positive difference for you?’ One of the things we notice when asking such questions is that different things motivate and energise different people. That is, of course, one of the tricky parts of leading any team. So a next question to pose could be something like, ‘What would it take for this team to feel more like that, more of the time for you?’ and to see what the wider team is willing to accommodate or negotiate. Now back to the model with some sample prompts to check out and navigate with a client, group or team. Notice how the different areas overlap and impact on each other. It’s about addressing all areas, not just to one or two in isolation. However, having explored each area in whatever way or level suits your situation, you are free to focus your efforts on those that need special attention. Goal: ‘What’s your vision for this?’, ‘Why this, why now?’, ‘What are you hoping for?’, ‘What would make a great outcome for you?’, ‘What would be the benefits of achieving it or the costs of not achieving it?’, ‘Who or what else is impacted by it and how?, ‘Where would you like to get to by the end of this conversation?’, ‘An hour from now, what would have made this worthwhile?’ Content: ‘What’s the most important issue to focus this time on?’, ‘What is the best use of our time together?’, ‘What is the issue from your perspective?’, ‘How clear are you about what this issue entails?’, ‘What feelings is this issue evoking for you?’, ‘What do we need to take into account as we work on this together?’, ‘Do we have the right information and expertise to do this?’ Process: ‘How would you like to do this?’, ‘What approach would you find most inspiring?’, ‘What might be the best way to approach this given the time available?’, ‘Which aspects to we need to address first before moving onto others?’, ‘What would be best to do now and what could be best done outside of this meeting?’, ‘Could we try a new way that would lift our energy levels?’ Relationship: ‘What’s important to you in this?’, ‘What underlying values does this touch on for you?’, ‘How are you impacted?’, ‘How are you feeling?’, ‘What are you noticing from your unique perspective?’, ‘What distinctive contribution could you bring?’, ‘What is working well in the team’s relationships?’, ‘What is creating tension?’, ‘How could we resolve conflicting differences?’ The versatility of the model is that it can be reapplied to coaching, training and other contexts too. In a training environment you could consider, for instance, ‘What are we here to learn?’ (goal), ‘What material should we cover?’ (content), ‘What methods will suit different learning styles?’ (process) and ‘How can we help people work together well in this environment?' (relationship). In a coaching context it could look something like, ‘How do you hope to develop through engaging in this coaching experience?’ (goal), ‘What issues, challenges or opportunities would you like to focus on?’ (content), ‘How would you like to approach this together?’ (process) and ‘What would build and sustain trust as we work on these things together?’ (relationship). I’d be interested to hear from you. Do the areas represented in this model resonate with your own experiences? Which factors have you noticed tend to be most attended to or ignored? Do you have any real-life, practical examples of how you have addressed these factors and what happened as a result? In your experience, what other factors make the biggest difference? My boss had been reading John Ortberg’s ‘Everybody’s Normal Till You Get to Know Them’ and it was time for us to plan our annual leadership team retreat. Looking for a theme title, he suggested half-jokingly, ‘How about ‘Everybody’s Weird’?’ I laughed at first but then thought for a moment…what a great concept and idea. It felt inspired. How to blow away any sense of normality and conformity and to meet each other afresh as we really are. Our creativity lies in our unique weirdness and what a great way to explore our individual quirkyness and its potential for the team and organisation.

Every group, every team, develops its own normative behaviours. Some even prescribe them by developing explicit competency and behavioural frameworks. It provides a sense of identity, stability and predictability. It can also improve focus and how people work together by establishing a set of ground rules, how we can be at our best. The flip side of all of this is that a team can begin to feel too homogeneous, too bland. It can lose its creative spark, its innovative spirit. The challenge was how to rediscover our differences, our wonderful, exciting, diversity in all its weird complexity. We invited people to bring objects that represented something significant in their personal lives and to share their stories. We invited people to use psychometrics to explore their preferences to shared them in the group. We invited them to challenge the psychometric frames, not to allow themselves to be too categorised. We invited people to challenge stereotypes, to break the moulds they felt squeezed or squeezed themselves into, to look intently for what they didn’t normally notice in themselves and each other, to allow themselves to be surprised and inspired by what they discovered. It felt like an energetic release. People laughed more, some cried more, others prayed deeply together. The burden of leadership felt lighter as people connected and bonded in a new way. It felt easier to challenge and to encourage. By relaxing into each other and themselves, people became more vibrant, more colourful, less stressed. They saw fresh possibilities that lay hidden from sight before. They discovered more things they liked about each other, fresh points of common passion, interest and concern. They built new friendships that eased their ways of working. It felt more like team. What space do you and your organisation allow for weirdness? Do you actively seek, nurture and reward differences? Do your leadership style and culture bring out and celebrate individuals’ strange idiosyncracies, each person’s unique God-given gifts, talents and potential? Have you had experiences where a capacity for weirdness has enhanced your team or organisation’s creativity and innovation? Do you risk inadvertently squeezing out the best of weirdness by policies and practices that drive towards uniformity? Could a bit more weirdness be more inspiring and effective – and fun?! :) I met with a group of Christian bikers yesterday who were discussing the Paris to Dakar rally. During the course of the conversation, the group leader spoke about the incredible teamwork and logistics involved in achieving success in such a gruelling event. He compared it by analogy to supporting each other as friends and fellow bikers on an exciting yet demanding journey of faith. He mentioned how we sometimes talk about the ideal team as a ‘well-oiled machine’. It was certainly a metaphor that appealed to the group. He went on, however, to challenge the metaphor. ‘A team isn’t a machine. It’s people. People like us. People like you and me. People who are different to each other, each with their own personality, talents – and quirky habits.’ He went on. ‘It’s that kind of team that I want to be part of. A team of friends who care deeply about each other, look out for each other, support each other, laugh together, cry together, pull together. A machine does none of those things. It’s cold, efficient, impersonal, inhuman. The machine metaphor is all about performance. The team I’m talking about is all about relationships.’ One bloke piped up with a playful glint in his eye. ‘This group is nothing like a well-oiled machine. It’s more like a buckled wheel – and I love it!’ As I looked around the room at these leather clad men, each with his own mixed life story of brokenness and success, I could see what he meant. There’s something about this team that's intensely human, personal and real. I reflected more as I rode home. I thought back to teambuilding events I’ve been involved with, team coaching experiences, team models and technical scientific psychometrics. This man wasn’t simply advocating a different team model to the norm, a different team focus or approach. He was advocating a radically different existential–spiritual paradigm to that we find in many Western organisations today. He was challenging an over-emphasis on performance and efficiency that loses sight of humanity and meaning. I was taken back to a conversation with an African colleague who once commented, ‘I know Western organisations are preoccupied with targets and metrics. Our invitation, however, is to meet with us as people and to walk together.’ Is this hopelessly naïve, idealistic and unrealistic? What about all the pressures organisations face in increasingly competitive markets? What about increasing demands from boards, employees and shareholders for greater accountability, productivity and profits? What about organisational cultures that foster internal competition too? I agree, it’s a real challenge. It calls for visionary, courageous leadership, a radical step back to consider deep questions of identity, meaning and purpose at organisational and wider stakeholder levels. It begs profound questions, e.g.‘What is influencing our beliefs about what is most important to us?’ ‘What is driving our behaviour?’, ‘How can we be more human?’, ‘What legacy do we want to leave in the world?’ I’ve had the privilege of working with some leadership teams that have taken this challenge seriously. Admittedly, it felt counter-intuitive at the time, especially at first. How to build in a more explicit spiritual-humanising dimension to the organisation’s thinking, practice and culture in the midst of intense organisational busyness, pressures and deadlines? Wouldn’t it take more time than was available, slow things down? I could feel the understandable tension alongside the aspiration. One team decided to bite the bullet. Its 2hr meetings had constantly packed agendas. It struggled to work through everything and the pressure felt relentless. Some felt tired and wondered in conversations offline about their team’s sustainability and their own ability to cope. We discussed how it would feel to check in with each other and with God at the start of each meeting - and they were open to experiment. We decided to allow 20 mins of each 2 hour meeting so that people could arrive and breathe before diving into business. As they settled in, they shared stories of how they were feeling, what was happening in their worlds at the moment, what was preoccupying them. They practised active listening, being genuinely present to each other. Sometimes they prayed. At the end of the 20 mins, they felt more relaxed and focused with a stronger sense of team spirit. They used the next 5 minutes to revisit the agenda: ‘What now stands out as most important to us?’ ‘How shall we do this?’, ‘What do we need to do this well?’ The team commented after practising this for a few months on how it had transformed their relationships and meetings. Their times together felt more focused, inspiring, energising, open, honest, human, and productive. They achieved higher quality and faster results. They began to identify ways of working that served them well (e.g. speak up; hear well; challenge; support) and used bright green cards light-heartedly to signal and affirm when anyone in the team modelled those behaviours. When others joined them for their meetings, they explained their new team culture and invited them to join in too. The effect was electric. It modelled inspiring team values and effective ways of working that extended beyond the team into the wider organisation. So, some questions for reflection. What difference do you, your team and organisation want to be and to make in the world? How far and how often do teams you are part of feel and act like a human place? What are your best and worst experiences of team? What made the biggest difference? What kind of person, team or organisation do you aspire to be and become? What kind of personal, team and organisational leadership will it call for to succeed? What will 'success' look and feel like for those involved and impacted by it? What values, practices and culture will others notice characterise your team? What place, if any, do God, spirituality and prayer take in your thinking and practice as a team? I would love to hear from you! ‘Could you be more direct?’ I took part in a 2-day workshop recently, a Gestalt approach to conflict, challenge and confrontation in groups. There were 12 in the group, mostly therapists of one kind or another, and we started by introducing ourselves in 2s. ‘This is my life’ in 5 minutes. Next, after each had spoken, we commented on what we had noticed. ‘We’re the same in that…’ and ‘We’re different in that…’ It drew our attention to what we notice in first encounters and how we tend to deal with sameness and difference in groups.

There’s something about sameness that can provide a sense of comfort, of security, of being part of something bigger than ourselves. When we feel insecure, we may seek out points of sameness in order to build rapport, establish connection and thereby reduce our anxiety. Safety in numbers. In this context, difference can feel distancing, even threatening. If we continue to focus on sameness, an awareness of group identity emerges, a feeling of belonging, a sense of differentiation between the ‘us’ and the ‘not us’. This is an important principle in group and inter-group dynamics. The inclusive dynamic that creates a sense of group within a group is the same dynamic that can exclude others. If we focus exclusively on sameness within our group and on difference between our own group and other perceived groups, we create boundaries between us. If difference emerges within our group, we may ignore or resist it because it doesn’t fit the group norm, the norm we have subscribed to in order to feel secure. This can lead to collusion and group think. A way to break through unhelpful group and inter-group barriers is to acknowledge what the group provides for us, its functional value at a social psychological level, and yet also to draw our attention to the differences between us within the group and the similarities between us (or at least some of us) and those (or at least some of those) in other groups. This has the effect of raising fresh awareness, reconfiguring group identities, enabling us to see different patterns of sameness and difference and thereby fresh possibilities. A later activity in this workshop was to practice immediacy. We split into two groups. One group sat in a circle in the middle of the room, the others around the outside observing those in the inside circle. The inside group was invited and encouraged to practise speaking very honestly, clearly and directly with one another. The conversation started.‘I would like to facilitate the group.’ ‘I’m happy for you to facilitate.’ ‘I feel anxious.’ ‘What do you feel anxious about?’ ‘I feel anxious in case those on the outside judge my performance.’ It continued. ‘If I lose interest, I will check out.’ ‘What will checking out look like, what will we see?’ ‘I will gaze out of the window’.‘What do you want us to do if we see you gazing out of the window?’ ‘Call it.’ ‘I don’t know what you are thinking or feeling and I want to know.’ ‘Why is that so important to you?’ ‘Because I don’t feel a connection with you, I feel distant from you.’ Our task was to focus on what was happening within and between us here and now and to articulate it openly and courageously, even if it risked evoking conflict. Asking, ‘What is happening here and now?’ is such a powerful question. It draws attention of a group away from a topic, issue or abstraction into the immediate moment. ‘I’m thinking…’, ‘I’m feeling…’. The impact in the workshop group felt both profound and electric. To ask, ‘What is going on for me now?’ is a great way of establishing contact with myself. To articulate what I am thinking and feeling in a group or to hear others do the same invites others to be open too and, thereby, builds the quality of relational contact within the group. This can prove tricky cross-culturally, especially where it could be considered inappropriate, disrespectful or even offensive to speak out in a group. In other situations, it may simply feel too risky to acknowledge openly what I’m thinking or feeling. The challenge in this workshop was to experiment with being more open, less constrained, than we would normally behave. ‘If I asked you on a scale of 10 how honest and up-front you are in groups, what would you say? What would really happen if you were to ratchet it up a notch?’ You may have heard it said, the longest journey a person must take is the eighteen inches from the head to the heart. It’s as if we can grasp an idea rationally, conceptually and yet still not allow it to touch us, to move us, to motivate us into action. What is this journey from passive assent to active commitment? What does it take to engender and sustain genuine engagement? What could it entail, look and feel like in practice?

I did some work with a leadership team recently. In conversation beforehand, it was clear they believed that certain behaviour changes would enhance their effectiveness. They were convinced in principle about this but hadn’t yet tried it. At this stage, it felt like a proposition, a possibility. It was still at the head level, a compelling idea that made good sense rationally. We decided to experiment to see what would happen experientially. The team chose three principles to focus on and practice. ‘Let’s be aware of space and pace (ensuring the right time and speed for each topic); rationality and intuition (being sensitive to analysis and feeling or discernment); speaking and listening (saying honestly what we are think and feel and tuning in to hear each other).’ We invited each other to hold up a green card each time we saw these principles being modelled. It felt a bit clunky at first but the team members gave it a go and the effect was amazing. The conversation felt focused, deep and purposeful. The quality of contact between participants was enhanced and the work became more inspiring and effective. We paused to reflect on how well the team was modelling these principles at the end of each meeting and, over a short space of time, the impact was transformational. I facilitated another group recently on solutions-focused brief coaching. It was a 90-minute workshop, a new event designed to inspire and equip leaders with a fresh approach to relationships. I wanted participants to leave with an experience of the difference this approach could make, to feel the positive impact rather than simply to understand the principles and concept. The participants were enthusiastic and gave it a go. We opened the workshop by inviting each person to share a current issue with the person beside them. The other person’s role was simply to help them think it through. The conversation had a 7 minute time limit, at the end of which they would reverse roles and repeat. We ended that piece by asking participants to give and receive feedback on how they had experienced the conversation, what had helped etc. I then introduced the core principles and sample techniques of solutions-focused coaching, working interactively with the group to flesh them out. We looked at contracting, solutions-focused vs problem-solving questions and moving towards action and commitment. The group grasped the principles but I wanted to progress the workshop from idea to experience, from conceptual understanding to compelling determination to follow it though. So I invited the group to run a second 7 minute conversation with the person beside them, this time consciously practising this new approach. Again, after 7 minutes they reversed roles and repeated, followed by giving and receiving feedback. The shift in experience was extraordinary. The participants looked surprised and pleased at such a marked shift in their own skill and the positive impact on their partners. The pivotal moment in each of these examples, in the team meeting and the coaching workshop, was the shift from rational awareness through physical/emotional experience to genuine conviction. Conviction based on experience can have a remarkable and truly transformational effect. It has the potential to lead forward from belief-in-principle to positive engagement, sustainable effort and profound change. Gestalt psychology emphasises the value of high quality contact, where contact is about presence, attention, engagement, relationship. I'm sure you've had the experience of being with someone who appeared bored or distracted. Conversely, think of examples when someone has really been there for you, with you, really listened hard. In that moment, you felt close, connected.

In the busyness of life, it can feel hard to stay in contact with ourselves, our physical environment, others around us. It's as if we live in a blur, a semi-conscious state, that deadens us to the richness of life and real engagement. It's a survival strategy, a way of dealing with complex pressures and demands, that can nevertheless leave us feeling empty, alientated, lifeless. We can experience the same in our spiritual lives too, vaguely aware of a Presence that lies beyond but largely drowned out by other activities and preoccupations. We get bored, restless, dissatisfied, exhausted. Christian life can feel like a concept, an abstraction, a memory rather than a vibrant, life-giving relationship in the here and now. In order to re-establish contact, a Gestalt therapist may encourage a person to pause, sit, notice what's going on in and around them at that very moment...thoughts, feelings, breathing, sights, sounds, their own body. The aim is to help raise into awareness that which lies buried, ignored, suppressed or unnoticed. It's about exploring the 'what else' of a person's experience. Take 5 minutes. Allow yourself to relax. Notice your breathing. Notice your body, how you are sitting, how you are feeling in different parts of your body. Notice how you are feeling, where you are feeling it. Notice what thoughts are drifting through your mind, what is preoccupying you. Look and listen, what do you notice in the room, sights, sounds, smells, what do you notice outside? This kind of practical exercise draws our attention away from the past or the future into the present. Now practice being present, really present to another person. Allow that person to fill your attention. Notice how they look, listen to them attentively, tune into how they are feeling. Notice how giving attention affects the quality and feeling of contact between you. These principles are really important in Christian leadership. It's about paying attention to how we arrive in meetings and enable others to arrive. It's too easy to rush in, race ahead with an agenda, without really first becoming present to and with one another. It's about how to establish high quality, meaningful contact with oneself, others in the room and God, to really hear and discern. (I love Richard Rohr's comment in Things Hidden: 'God's face is turned towards us absolutely...it is we who have to learn, little by little, to return the gaze.' It conveys the profound and startling revelation that God is already present to us, already in deep contact with us. In this sense, spirituality is something about becoming present to the Presence, the God who is already with us.) Take an aide-memoire into your next meeting. Ask yourself silently, 'What is the quality of my contact with myself...with the other people in the room...with God...with the subject matter we are considering?' 'What can we do to improve the quality of contact in order to bring out the best in ourselves and each other?' You may be amazed at the difference it can make. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed