|

‘Leadership is influence.’ (John C. Maxwell) It’s one thing to have insight. It’s another thing to exert influence on the basis of that insight. This is often a dilemma for leaders and professionals when seeking to influence change across dynamic, complex systems and relationships. After all, what if I can see something important, something that could make a significant difference, yet I can’t gain access to key decision-makers? Or what if, even if I can get access, they’re not willing to listen? What if people are so preoccupied by other issues that my message is drowned out by louder voices and I can’t achieve cut-through? Early in my career, I worked as OD lead in an international non-governmental organisation that was about to embark on radical change. I’d studied OD at university on a masters’ degree course and, based on that experience, could foresee critical risks in what the leadership was planning to do. I tried hard to get access to raise the red flags but, by the time I met with the leaders, it was too late. They had already fired the starting gun on their chosen programme. My concerns turned out to be well-founded, and the changes almost wrecked the organisation. I agonised for some time over why I’d been so ineffective at influencing their decisions. I learned some valuable lessons. Firstly, the view I held of my role – the contribution I could bring – was different to that of the leaders. I viewed myself as consultant whereas they viewed me as service provider. Secondly, the leaders had become so emotionally-invested in the change they had designed that they reacted defensively if challenged. They saw my well-meaning red flags as resistance rather than as a genuine desire to help. I would need to change my approach. Since then, I have practised building human-professional relationships with leaders and other stakeholders from the earliest opportunity. These relationships are built on two critical factors: firstly, respect for e.g. the studies, training, expertise and lived experience they bring to the table; and, secondly, empathy for e.g. the responsibilities, hopes, demands and expectations they face – both inside and outside of work. Against this backdrop, I’m able to pray, share my own insights and, where needed, advocate a change from an intention and base of support.

12 Comments

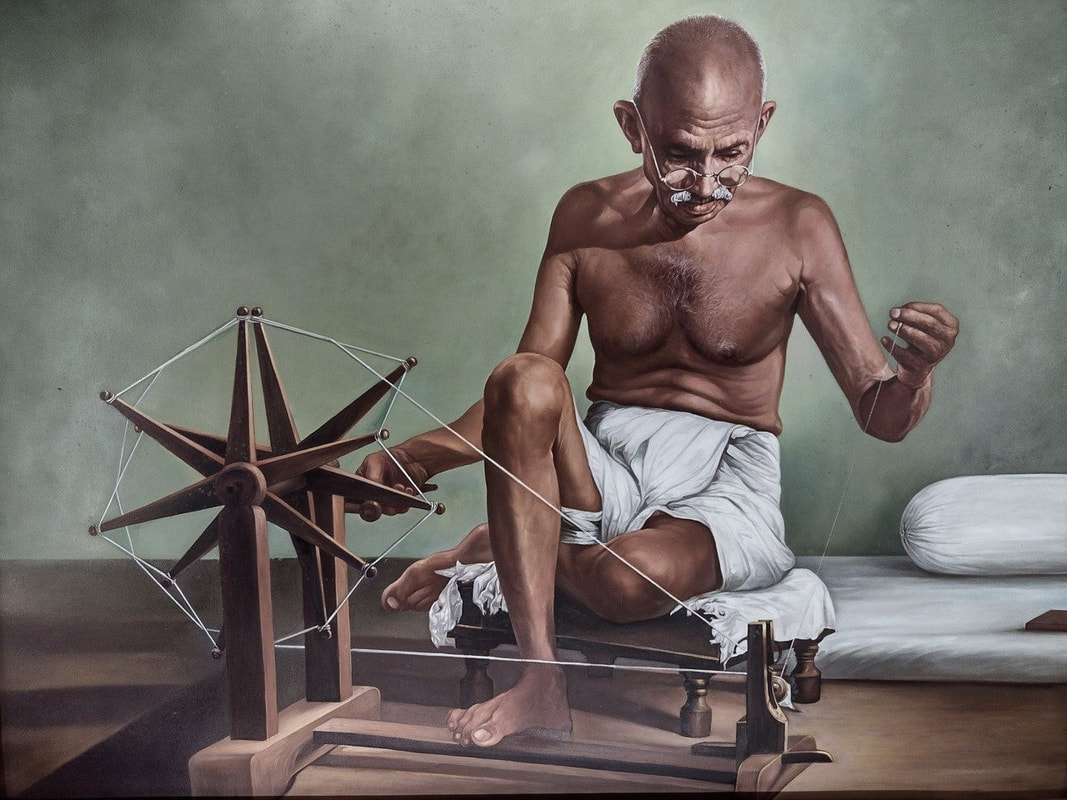

‘Anyone can be a Father – but it takes someone special to be a Dad.’ (Wade Boggs) Father’s Day will feel very different this year. My Dad died recently and, no matter how old a person is when they pass away, to me he was still my Dad. That gave him a unique place in my life and a special relationship in my world of experience. To be honest, on reflection, I don’t think I ever knew my Dad that well. Yes, we shared lots of different times together over the years and I have all kinds of memories of him, but that’s not the same as…really…knowing…someone. He came from a generation that didn’t really disclose or expose deep feelings. As a child, I looked up to him as a strong, dependable figure in my life: someone I respected, sometimes from a relative relational distance. He was a motorbike fanatic and had a significant influence on my love for motorcycles and motorcycling, as he did on my brothers too. He was great at DIY – a talent that, sadly, I didn’t inherit from him – and could build or repair just about anything. I hadn’t really realised until we were preparing for his eulogy that I had never heard him once speak badly about anyone. He was a man of integrity and kept his silence. Two weeks before Dad died, I was called back urgently from Germany. He had had a fall, with complications, and the doctors didn’t expect him to survive. I raced to the hospital and, thank God, had time with him. He was vulnerable. I stayed overnight, tried my best to advocate for him and fed him gently when he could no longer feed himself. I plucked up the courage to tell him, for the first time, that I loved him. He told me, for the first time, that he loved me too. The day before he died, he whispered, ‘Thank you for everything you have done.’ I cried. I had never felt closer to him than in those precious, painful moments. A beautiful sadness. Dad – I will never forget you. ‘Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is one of the longest words in the dictionary, and ironically, it means the fear of long words. It originally was referred to as Sesquipedalophobia but was changed at some point to sound more intimidating.’ (Yalda Safai) You couldn’t make it up. Who would create a word like that – and why? One theory is that all professional fields create their own jargon, partly as a convenient shorthand for people working in that field and partly as an implicit status symbol. After all, if I know what the words mean and you don’t, that places me on a pedestal. It signifies I’m an expert – and you’re not. I did some work with a professional UK charity that wanted to change its brand tone of voice. (There you go: a bit of brand jargon). 'Tone of voice' means something like 'organisational personality'. Essentially, they wanted to change the way they express themselves in order to change the way in which they are perceived and experienced by those they want to work with. As part of the change, they decided to write in ways that one might ordinarily speak. It’s one of those curious cultural things in English, like in some other languages too, that we tend to write in one way and speak in another, even using different words to mean the same thing. Spoken words tend to be simpler and shorter. So, they set about de-jargonising their written jargon. Here are some examples they used to illustrate this principle, replacing written language with spoken – request: ask; require: need; advise: tell; retain: keep; endeavour: try; terminate: end. This made their communications feel less formal and more personal and conversational; especially when they also used first and second person (I/we/you) pronouns and active voice. (See how I slipped in a bit of grammatical jargon there?). So, language is important. A change of language can reshape the ways in which people and groups perceive, experience and relate to us, and to one-another. Language carries subtle emotional and cultural associations too, influencing how we (and others) feel, what we believe – and how we are likely to respond. ‘Education consists of two things: example and love.’ (Friedrich Fröbel) I can’t remember last time a book gripped me as much as, Mahatma Gandhi Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments with Truth. (I’m trying very hard to read it slowly and thoughtfully so that I don’t get to the end too quickly). Perhaps it was Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa: An Authorized Biography. The next two books on my reading list are: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and St. Francis and His Brothers. There’s something about reading the lives of these ordinary-extraordinary people of faith that always humbles, challenges and inspires me. I want to be more like them. They help keep my own life and work focused and in perspective. I have to remind myself: these were ordinary people, just like me, who became extraordinary through the life decisions they made. They proved in practice that faith is acting on what we believe as if it were true. They lived out: ‘put your body where your mouth is.’ At times, it can feel like standing vulnerable and naked in front of a mirror and seeing my own life, decisions and actions in sharp comparison and stark contrast to theirs. Yet I don’t want to be a carbon copy. I’m not in their situations and I’m not who they were in those situations. I’m me – and I’m here and now. This is my time, my place and my opportunity. I want to follow God’s distinctive call on my own life with authenticity and integrity, to be the very best version of me that I can be in His eyes. Who are your role models? What impact do they have in your life? ‘People get tired of asking you what's wrong and you've run out of nothings to tell them. You've tried and they've tried, but the words just turn to ashes every time they try to leave your mouth. They start as fire in the pit of your stomach but come out in a puff of smoke. You are not you anymore. And you don't know how to fix this. The worst part is...you don't even know how to try.’ (Nikitta Gill) Losing my voice was a painful experience. It started with frequent sore throats and laryngitis but steadily got worse. After a while, I had to suck on throat lozenges to be able to speak at all. My voice became very weak and, if I had to project it in a group or tried to sing, it felt afterwards like I’d been garrotted. Feeling increasingly concerned, I saw my doctor who referred me to ear-nose-throat specialists. They ruled out throat cancer and vocal cord nodules yet still couldn’t work out what was causing the problem. I lost count of how many cameras they ran up my nose and down my throat. As time went on with no improvement, they referred me to speech therapy. By now I was having to carry a sign at work to say, ‘Sorry, I’ve lost my voice’ and a clipboard to write down what I wanted to say. (It was amusing to see how many people wrote down their responses for me to read too. I had after all lost my voice, not my hearing.) The speech therapists were puzzled by the symptoms and tried various techniques without success. For 2 years, I virtually couldn’t speak at all. It took another 10 years of cameras and speech therapy before they finally worked out the underlying problem. Bizarrely, I had somehow learned to speak as a child without using the complex muscles around the larynx correctly. It was, in effect, as if I had found a way to imitate normal speech. That was OK to a point, until my work demanded more strenuous use of my voice. That’s when it became strained and failed. Apart from the intense physical discomfort, the social and psychological effects were profound. Over the years, I got tired of explaining my predicament. I became far quieter than usual and people related to me as if I was incredibly introverted, or simply didn’t relate to me at all. It became so very isolating. Not only did I lose my physical voice. I felt steadily as if I was losing my personal identity, presence and influence in social situations too. I felt helpless to resolve it and had no idea if it could or would ever be resolved. Salvation came in the form of a new friend, David, whom I met in a church and who had suffered from debilitating hearing loss for many years. When he described the social and psychological effects it had had on his life, for the first time I didn’t feel alone. It demonstrated the power of empathy and its place in healing. Now I could learn to speak. ‘Just like seasons change in nature, they change in our lives as well. And, as they change, they ask different questions of us. What questions is your life asking of you now?’ (Funmi Johnson) I had a great conversation with Funmi, a fascinating and inspiring fellow coach, this afternoon and found her question (above) very thought-provoking. I’m at an age where legacy is a persistent question that calls out to me with growing insistence…and demands a response. Am I genuinely living my life authentically according to the mission and values that I claim to be real and true? Or am I compromising too much of what matters most, deluding myself with a clever façade that even I have found convincing? How deep will my spiritual footprint be? I love Funmi’s question. It stirs the waters and ignites a search. ‘When trouble arises and things look bad, there is always one individual who perceives a solution and is willing to take command. Very often, that person is crazy.’ (Dave Barry) We can think of leadership as the property of a structure, in which a person designated as a 'leader' holds particular responsibilities and has, at least in principle, the hierarchical authority needed to fulfil them. We can also think of leadership as an intrinsic property of an individual. In this sense, leadership is something that resides within and emanates from a person, something that she or he has and does. This is the realm of competency frameworks and of leader-development initiatives. We can also think of leadership as the property of a group; for instance, a leadership team. In this idea, shared leadership is something exercised by a collective, where a diverse united group is, in potential, more than the sum of its parts. We can also think of leadership as a property of a dynamically-complex eco-system, in which acts of leadership emerge, sometimes unexpectedly and from unexpected places, and exert influence. This is the arena of dispersed and distributed leadership. In organisations, I’m finding the latter perspective especially useful. When working with leadership teams, I invite participants to reflect on the eco-system (cf Gestalt: field) as a whole; for instance: 'Where is leadership-as-influence exercised, inside or outside of the organisation’s boundaries? What are the distinctive roles and responsibilities of different 'leadership' entities within the system? What are the relationships between them? What does each need from the others to be effective?' I notice this invariably opens up far deeper, wider and richer conversations than those that focus on individual leaders alone, or leadership teams in isolation, as if they exist in a cultural-contextual vacuum. Some people find it useful to experiment with mapping their eco-system graphically, recognising that any depiction will reveal and, therefore, create opportunity to open up to healthy exploration and challenge, the way in which they construe their reality and leadership dynamics within it. ‘When the world is silent, even one voice becomes powerful.’ (Malala Yousafzai) It’s about influencing, convincing, persuading – often with or on behalf of vulnerable people or groups who may lack the power, opportunity or safety to do it alone or for themselves. It always focuses on change, typically hoping to create a shift in strategy, policy or practice. My earliest attempts at advocacy were in my early teens, campaigning against brutal mistreatment of animals in Spanish bull-fighting. In my later teens, I moved into human rights work to campaign vociferously against horrific political abuses and atrocities in El Salvador. In retrospect, I do wonder if my energetic beating of the drum achieved anything. My approach was certainly driven by passion, confronting head-on what I saw as critically important ethical issues. I would argue my case forcefully, growing ever-more skilful at constructing a stance based on sound evidence and, I hoped, near water-tight rationale. I was galvanised in this conviction and activism by my new-found faith as a follower of Jesus, and by biblical injunctions to: ‘Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy’; ‘Defend the weak and the fatherless; uphold the cause of the poor and oppressed.’ In later years, I became increasingly convinced by the need for a radical change in my approach. There are occasions on which direct polemic is needed, for instance: for sake of conscience, to take a clear and unambiguous public counter-stance on an issue, irrespective of whether it will win the day. In many cases, however, I’ve found that prayer, empathy and diplomacy are more effective and less likely to provoke a defensive response. Diplomacy doesn't mean compromise. It does, however, call for humble respect; to see and relate to the ‘other’ as human, with their own hopes, anxieties, interests, pressures and concerns. John M. Lannon proposes 4 main strands to this approach: ‘Show empathy; Acknowledge opposing views; Maintain a moderate tone; Use humour where appropriate.’ To show empathy is to identify with the others’ feelings and to express genuine interest in their best interest. To acknowledge opposing views is, before arguing your own case, to show respect for the other by acknowledging any merits in their position. To maintain a moderate tone is to resist overstating your case and stay away from emotionally-loaded words. To use gentle humour can ease the tension in a situation, depending on the nature of the relationship. Some of the most inspiring role models in my own advocacy work have been: Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Bob Hunter, Archbishop Oscar Romero, Jasmin Philippines, Mike Gatehouse, Sister Isabel Montero, Andy Atkins, Rudi Weinzierl, Mike Wilson, Greta Thunberg, Malala Yousafzai and Ruth Cook. Their approaches have all broadly been characterised by what the founders of Greenpeace saw as as 5 core elements and stances in world-changing individuals and movements: ‘Plant a mind bomb; Put your body where your mouth is; Fear success; The revolution will not be organised; Let the power go.’ ‘Where words fail, music speaks.’ (Hans Christian Andersen) Music, like all forms of art, can bypass the rational filters of our minds and express or transport a message, a mood, deep into our bodies and souls. Many of the earliest musical influences on my own life had a profoundly existential feel, including Pink Floyd’s Time and Supertramp’s Logical Song. These songs have continued to carry that same resonance throughout my life, reflecting and reinforcing a deep sense of restlessness, resistance and reaching. Others have had a more overtly spiritual influence, including Tim Rice’s and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar and U2’s Under a Blood Red Sky. They lifted me out of myself, helped make sense of what I knew and felt intuitively and galvanised my stance of faith. Some gave voice to the deep angst and discordant dissonance I felt in my life and in the world, including David Bowie’s Scream Like a Baby and The Saints’ This Perfect Day. What music or songs have had the deepest resonance or impact in your life? ‘How is that human systems seem so naturally to gravitate away from their humanness, so that we find ourselves constantly needing to pull them back again?’ (Jenny Cave-Jones) What a profound insight and question. How is that, in organisations, the human so often becomes alien? Images from the Terminator come to mind – an apocalyptic vision of machines that turn violently against the humans that created them. I was invited to meet with the leadership team of a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in East Africa that, in its earnest desire to ensure a positive impact in the lives of the poor, had built a bureaucratic infrastructure that, paradoxically, drained its life and resources away from the poor. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. I worked with a global NGO that determined to strengthen its accountability to its funders. It introduced sophisticated log frames and complex reporting mechanisms for its partners in the field, intended to ensure value for its supporters and tangible, measurable evidence of positive impact for people and communities. As an unintended consequence, field staff spent inordinate amounts of time away from their intended beneficiaries, completing forms to satisfy what felt, for them, like the insatiable demands of a machine. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. A high school in the UK invited me to help its leaders manage its new performance process which had run into difficulties. Its primary focus had been on policies, systems and forms – intended positively to ensure fairness and consistency – yet had left staff feeling alienated, frustrated and demoralised. We shifted the focus towards deeper spiritual-existential questions of hopes, values and agency then worked with groups to prioritise high quality and meaningful relationships and conversations over forms, meetings and procedures. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. Academics and managers at a university for the poor in South-East Asia had competing roles and priorities, and this had created significant tensions as well as affected adversely the learning experience of its students. The parties had attempted unsuccessfully to resolve these issues by political-structural means; jostling behind the scenes for positions of hierarchical influence and power. They invited me in and we conducted an appreciative inquiry together, focusing on shared hopes, deep values, fresh vision and a co-created future. The challenge and solution were to rediscover the human. Where have you seen or experienced a drift away from the human? Curious to discover how I can help? Get in touch! |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed