|

‘The people living in darkness have seen a great Light; on those living in the land of the shadow of death, a Light has dawned.’ (Matthew 4:16, the Bible) ‘Death is a thick black wall, against which every soul is hurled and shattered.’ I don’t now remember who said that, but I do remember my philosophy lecturer quoting it when we studied existentialism. These are very dark words indeed and have, for me, a deeply foreboding and chilling feel to them. I sat down and avidly wrote an essay in response, doing my best to present what, I believed, were convincing rational arguments to counter such a nihilistic and hope-less outlook. When I got my paper back, the mark was nowhere near as high as I had hoped for or expected. The lecturer had commented simply yet profoundly that an existentialist writer would have absolutely no interest in my reasoning. It’s not about objectivity or logic. It’s about how it is and feels to be in the world; a phenomenological cry of angst in the face of fragile, fathomless, futility. It was as if, in my attempt to offer ‘correct’ thinking, I had totally missed the point. It never was about thinking. As the years have passed by, I too have known that angst, at a times an almost irresistible magnetic-like pull towards my own death. Sometimes, it has felt like half-clinging on weakly to avoid being pulled over the edge. In the face of unbearable and irreparable heartbreak, suicide can feel like a least-painful solution. Tom Walker’s moving song, Leave a Light On has deep emotional resonance here. Jesus is my life-saving Light. ‘At the end of the day, it’s either God or death.’ (James Wallace). Whatever Advent means to you, Light shines in darkness. Hold onto hope.

22 Comments

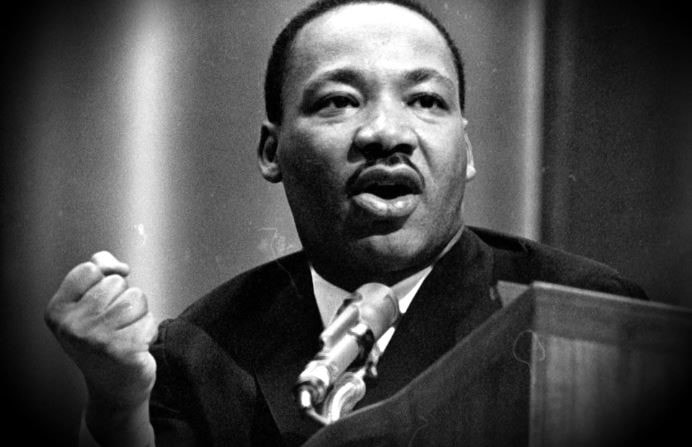

'The optimism of the action is better than the pessimism of the thought.' (Greenpeace) Resilience is a common buzz word today, partly in response to the complex mental health challenges that individuals and communities face in a brittle, anxious, non-linear and incomprehensible (BANI) world. Who would have imagined 3 years ago, for instance, that Covid19 would strike or that Russia would invade Ukraine, with all the ramifications this has precipitated in our personal and collective lives? It can feel like too much time spent on the back foot, reacting to pressures that may appear from anywhere, without warning, from left field – rather than creating the positive future we hope for. A psychological, social and political risk is that people and societies develop a ‘Whatever’ attitude, an apathetic ‘What’s the point?’ mentality. After all, what is the point of investing our time, effort and other resources into something that could all get blown away again in a brief moment? A good friend worked in Liberia with a community that was trying to recover from the effects of a bloody civil war. They started to build schools, hospitals and other infrastructure and, just as things were beginning to look hopeful, a violent, armed militia swept through the area and burned everything to the ground. This can feel like an apocalyptic game of snakes and ladders. Take one step forward and, all of a sudden, back to square one again. A close friend in the Philippines befriended people in a very poor makeshift community, surviving at the side of a busy road in boxes and under tarpaulins. She worked hard to improve the quality of their lives, to ensure that they felt and experienced authentic love, care and support, and it started to have a dramatic human impact. Faces brightened and hopes were lifted. Then, out of nowhere, government trucks appeared and bulldozed that whole place to the ground. It could be tempting to give up. One coping mechanism is to focus on living just one moment, one day, at a time because, after all, 'Who can know what tomorrow will bring?' This may engender an element of peaceful acceptance, akin to that through mindfulness. It can also morph into a form of passive, deterministic fatalism: ‘We can’t change anything, so why try?’ Martin Luther King's response stands in stark contrast who, in the face of setbacks, advocated, ‘We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would more tragic than to stop at this point. We’ve got to see it through.’ Psychologically, both approaches could be regarded as survival strategies, as personal and social defences against anxiety. In a way, they are adaptive responses: ways of thinking, being and behaving that seek to create a greater sense of agency and control in the face of painful powerlessness. In the former case, a level of control is gained, paradoxically, through choosing to relinquish control. It's a letting-go rather than a clinging-on. In the latter, a fight-response (albeit a faith-fuelled, non-violent fight in the case of MLK), control is sought by changing the conditions that deprive of control. Each constitutes it's own way of responding to an external reality – and it’s out there as well as in here that the real and tangible challenges of resilience and transformation persist. The social, political and economic needs of the poorest, most vulnerable and oppressed people in the world don’t exist or disappear, depending simply on how we or they may perceive or feel about them. MLK’s call to action was radical: ‘We need to develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness. It’s no longer a question of what will happen to us if we get involved. It’s what will happen to them (and us) if we don’t?’ [See also: Resilient; When disaster strikes; Clash of realities] ‘If you want to know what your true values are, have a look at your diary and your bank statement.’ (Selwyn Hughes) Take any example of an important-to-you decision that you have taken during this past week. Consciously or subconsciously, directly or indirectly, it will have reflected something of your underlying beliefs and values. At one level, every decision we take with awareness represents the outcome of a choice point, analogous to a choice of a direction at an intersection in a road. Guiding principles are a way of choosing to align our decisions and behaviour with our beliefs, ethics and values. I worked with a group recently where, during feedback, participants commented on how they felt impacted by what they saw and experienced as my ‘distinctive’ style and approach. They were curious and asked me what, if anything, lay behind this – that which they had experienced – for me. What is it that makes the difference? I held up a small, yellow, post-it note to the screen. On it are written 3 words in my own scrawled handwriting: Prayer, Presence, Participation. These are, if you like, the guiding principles that underpin me personally and all of my work professionally. I carry them with me and have them stuck on my desk, beside the monitor. I pause and focus on them consciously and deliberately before, say, writing a message, joining a conversation or running a workshop. They really do matter to me. Prayer is inviting and opening myself to God’s insight, wisdom and power. He is able to reveal, do and achieve things that are truly impossible for me alone. Presence is ensuring quality of attention and contact with each person or group that I will meet. It’s viewing and approaching each person, each moment, as a sacred encounter. Participation is an invitational spirit that calls for humility and courage. It means engaging with people, not simply technology or any materials that we may use. At the end of the conversation, I invited each person in the group to reflect for a moment – for as long as they needed – and to write down 3 words that, perhaps, they would choose to underpin their own practice. They did this thoughtfully, alone, then each shared with others in the group what they had written. This felt so much deeper and more meaningful than simple words on paper could capture or convey. It was about integrity, authenticity and congruence: choosing to take a stance. What core principles guide the focus and parameters of your decisions and behaviour? What stance are you willing to take? ‘It’s a question of what the relationship can bear.’ (Alison Bailie) You may have heard the old adage, the received wisdom that says, ‘Don’t try to run before you can walk.’ It normally refers to avoiding taking on complex tasks until we have mastered simpler ones. Yet the same principle can apply in relationships too. Think of leadership, teamworking, coaching or an action learning set; any relationship or web of relationships where an optimal balance of support and challenge is needed to achieve an important goal. Too much challenge, too early, and we can cause fracture and hurt. It takes time, patience and commitment to build understanding and trust. I like Stephen Covey’s insight that, ‘Trust grows when we take a risk and find ourselves supported.’ It’s an invitation to humility, vulnerability and courage. It sometimes calls for us to take the first step, to offer our own humanity with all our insecurities and frailties first, as a gift we hope the other party will hold tenderly. It's an invitation, too, for the receiver to respond with love. John, in the Bible, comments that, ‘Love takes away fear’. To love in the context of work isn’t something soft and sentimental as some cynics would have us believe. It’s an attitude and stance that reveals itself in tangible action. Reg Revans, founder of action learning, said, ‘Swap your difficulties, not your cleverness.’ A hidden subtext could read, ‘Respond to my fragility with love, and I will trust you.’ I joined one organisation as a new leader. On day 3, one of my team members led an all-staff event and, afterwards, she approached me anxiously for feedback. I asked firstly and warmly, with a smile, ‘What would you find most useful at this point in our relationship – affirmation or critique?’ She laughed, breathed a sigh of relief, and said, ‘To be honest, affirmation – I felt so nervous and hoped that, as my new boss, you would like how I had handled it!’ In this vein, psychologist John Bowlby emphasised the early need for and value of establishing a ‘secure base’: that is, key relationship(s) where a person feels loved and psychologically safe, and from which she or he can feel confident to explore in a spirit of curiosity, daring and freedom. It provides an existential foundation on which to build, and enables a person to invite and welcome stretching challenge without feeling defensive, threatened or bruised. How do you demonstrate love at work? What does it look like in practice? ‘Respect deeply the otherness of the other.’ (Richard Young) Navigating boundaries is a critical skill in coaching and action learning. Anne Katharine describes this phenomenon succinctly in the subtitle of her book: Where You End and I Begin (2000). Incorporate Psychology provides a useful explanation of different kinds of relational boundaries and what can go wrong if they become blurred, enmeshed or rigid. Khalil Gibran writes poetically on this same theme in The Prophet (1923): ‘Let there be spaces in your togetherness. Let the winds of the heavens dance between you…Even as the strings of the lute are alone though they quiver with the same music.’ In coaching and action learning, a variety of boundaries emerge that we need to pay attention to for this work to be effective. In a coaching relationship, the coach and client learn to navigate these including: their respective roles and responsibilities; their places and times of meetings; their accountabilities to any wider stakeholders; the scope and parameters of what each will focus on, and not; their agreements on what will remain confidential, or not, and to whom. In action learning, further boundaries include those between facilitator and group, and those between different group participants and roles. At deeper human levels, Gestalt psychology speaks of confluence, where a boundary is dissolved and the quality of healthy contact is compromised. The coach and client, or action learning presenter and peers, need to differentiate between, for instance: what’s simply here-and-now and what’s transference from the past; what’s the coach/peers’ stuff and what’s that of the client or presenter; what’s just about the client or presenter and what’s a parallel process of wider systemic or cultural influences. Managing boundaries is, we discover, a key dimension to success in these fields. ‘I turned my head and saw yet another wisp of smoke, on its way to nothingness…’ (King Solomon) On three separate occasions, a female grass roots activist in the Philippines was followed at night by strangers: men on motorbikes. As she walked alone, they would ride slowly and menacingly behind her, aiming to threaten and intimidate her into silence. She had taken a very public stance against corruption in high places – a stance that, for other activists in her country, had resulted in a deadly blade or a bullet in the back from a passing motorcyclist. Undeterred, this young woman turned around and confronted the bikers, fearlessly: ‘Even if you kill me, you can’t take my life.’ She’s a radical follower of Jesus who has chosen a determined, startling and courageous life stance at the cutting edge of faith. It stands in stark contrast to the greyness of nothingness that the writer of Ecclesiastes speaks to at the start of this blog. It’s a spiritual-existential stance that holds the potential to transform…everything. Zoom out now, back to our own lives. Strip back the trappings and tear away the superficial facades. What lays behind and beneath for us? This is the deep stuff of spiritual and existential coaching. It touches on fundamental questions: identity, meaning, purpose and stance. ‘Human life must be risked if it is to be won.’ (Jürgen Moltmann). ‘If you risk nothing, then you risk everything.’ (Geena Davis). I don’t want my life to be a wisp of smoke. You? (See also: Deep; Spirituality in coaching; Existential coaching) 'Every now and then I guess we all think realistically about that day when we will be victimized with what is life's final common denominator - that something we call death. We all think about it and every now and then I think about my own death and I think about my own funeral. And I don't think about it in a morbid sense. And every now and then I ask myself what it is that I would want said and I leave the word to you. If any of you are around when I have to meet my day, I don't want a long funeral. And if you get somebody to deliver the eulogy tell him not to talk too long. Every now and then I wonder what I want him to say. Tell him not to mention that I have a Nobel Peace Prize - that isn't important. Tell him not to mention that have 300 or 400 other awards - that's not important. Tell him not to mention where I went to school. I'd like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others. I'd like for somebody to say that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to love somebody. I want you to say that day that I tried to be right on the war question. I want you to be able to say that day that I did try to feed the hungry. I want you to be able to say that day that I did try in my life to clothe the naked. I want you to say on that day that I did try in my life to visit those who were in prison. And I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity. Yes, if you want to, say that I was a drum major. Say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter. I won't have any money to leave behind. But I just want to leave a committed life behind. And that is all I want to say. If I can help somebody as I pass along, if I can cheer somebody with a word or a song, if I can show somebody he's traveling wrong, then my living will not be in vain.' (Martin Luther King Jr. - his final sermon, the day before his assassination in 1968) ‘Are we learning yet?’ (John Connor to the Terminator) ‘History never repeats itself. Every single historical moment is distinct from those past.’ (Angela Johnson). That said, we can and do well to learn from the past to help inform our decisions for the future. This is a core principle of Learning Reviews. Some years ago, Learning Reviews were a key part of knowledge management (KM). The idea of KM was to capture, distil and disseminate learning from projects, to save others in future from having to start from scratch or re-invent the wheel. Things became quite complex if, say, project participants had a vested interest (e.g. for competitive advantage) in retaining, rather than sharing, what they had learned from experience; or hidden factors that had influenced success in one instance or arena were subtly different to those in a new situation. Against this backdrop, KM evolved into wisdom management (WM), where those engaged in the process would critically-evaluate insights and ideas rather than simply re-apply them. I ran lots of Learning Reviews with international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), where I developed and practised an appreciative approach that I will share here. Imagine a grid with ‘What Went Well’ (WWW) and ‘Even Better If’ (EBI) as column headings; and ‘Why’, ‘What’, ‘How’ and ‘Who’ as separate rows. ‘Why’ focuses on purpose; ‘What’ on content; ‘How’ on methods; and ‘Who’ on people and relationships. I would give each key stakeholder a copy of the template in advance. At the start of a Learning Review meeting, I would invite participants to decide on key questions (e.g. ‘What are the questions that, if we were to answer them, would enable us to draw out key insights?’). Then, I would facilitate the group to engage in a process of critical reflexivity, addressing blind spots (e.g. ‘What assumptions are we making that could prevent us gaining deeper insights?') and hot spots (e.g. ‘What issues may we be tempted to avoid in case they feel too difficult or painful?’). This groundwork with a group at the outset often proved vital. It enabled participants to contract with me and with each other around issues such as trust, vulnerability, humility and courage, as foundations for the Review itself. We would then explore the Why, What, How and Who dimensions using the WWW and EBI philosophy and approach, working rigorously to identify the conditions (e.g. personal or broader contextual) that had contributed to what had been experienced. I would end the Review by inviting participants to identify and crystallise, out of all that had been considered and discussed, the top 3-5 critical success factors for initiatives of this type. The final challenge would be to articulate and publish the resulting discoveries as tangible, transferable recommendations that would be easily understandable and accessible to other leaders and participants in future projects, along with details of who to contact if further insight is needed. What have been your experiences of Learning Reviews? What have you learned through doing them? ‘To lead real change, it’s not enough to think outside of the box. We need to think outside of the building.’ (Rosabeth Moss Kanter) Picture this. I’m in a coaching conversation with Anna, a client who feels stressed. She describes it as being like trapped inside a box, with no way out; where the box is her organisation, her job, the role she’s in now. The narrative she’s telling herself is that she has no possibility to escape from the debilitating pressure she’s experiencing. Her scope of authority to influence change is too constrained and she’s expected to deliver against targets that feel impossible. She feels totally helpless and hopeless. I acknowledge and empathise with how Anna is feeling, then ask if she’d be interested to explore potential options that could be available to her. At first, she pushes back, as if instinctively. ‘I don’t have any options – that is the problem’. I ask, inquisitively, to test the boundary a bit: ‘You could leave?’ ‘I can’t leave’, she replies, immediately and forcefully, ‘I have a mortgage to pay’. ‘So, the mortgage is part of the box?’, I ask. ‘Hmm. I guess it is’, she replies, more thoughtfully this time. ‘What if you weren’t to pay the mortgage?’, I ask. She looks bemused. ‘It would mean I’d lose the house, of course’, she snaps. ‘And, if you lost the house?’ ‘That would be terrible’, she replies, ‘It’s my dream home.’ ‘So, the dream home is, perhaps, part of the box?’ I ask. Anna goes quiet. After a while, she looks up and responds, ‘I don’t want to lose my home.’ ‘So: it’s as if, to keep your dream home, you feel that you have no option but to stay in your current job to pay your mortgage?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Imagine now, for a moment, dismantling or breaking out of the box that you feel trapped in. If you were to imagine a spectrum of options, ranging from the status quo to what you might think of as a most extreme solution (the ‘nuclear option’), what might they be?’ Anna picks up a piece of paper and a pen and starts to write. ‘At the extreme end, I could sell the house and downsize to a cheaper house or location, then I could get try to get a less expensive mortgage, but I don’t want to do that.’ ‘At the other end, I could stay as I am and just accept that the frustration in my job is a price worth paying to keep the house that I love.’ ‘And..?’, I ask. ‘I guess I could apply for another job.’ ‘Say more?’ ‘Well, I could look at other jobs in my organisation.’ ‘Yet the organisation sounds like it may be part of the box too? What if you were to think outside of the box altogether?’ ‘True. I could look at job opportunities elsewhere, or even at a change of career that would feel more fun and fulfilling!’ ‘So, there are, perhaps, some options that could feel in tension for you? The house…or a career that could feel more fun and fulfilling? Which stands out as most important for you?’ ‘I hadn’t thought about it, but if I could find something I really love doing, I might just be willing to consider moving house to do it. Perhaps I’m allowing my attachment to the house to box me in.’ Suddenly, I see a lightbulb moment flash in her eyes. ‘Eeek…’ she says, ‘Perhaps the house is the box!’ Breakthrough. Anna has left the building. [See also: Boxes; Deconstructing the box; and Lateral instinct] ‘If the blade is not kept sharp and bright, the law of rust will assert its claim.’ (Orison Swett Marden) ‘Clients value moments when a (coach) listens in a way that allows them to know that they are being heard, shares a relevant reflection, or asks a question that makes it possible to see an issue from a different perspective. By contrast, the hope that (coaching) might make a positive difference may be terminally undermined by selective or inattentive listening, awkward or self-serving personal disclosures or interrogative lines of questioning.’ (Julia & John McLeod, The Significance of Being Skilful, Therapy Today, BACP, November 2022). Writing in the context of counselling and therapeutic practice (which I have taken the liberty of re-applying to coaching here), McLeod and McLeod comment that practitioners often associate skills practice with training at the start of their career, rather than with an on-going development journey throughout their career. Many of the skills themselves are common to ordinary human relationships. ‘(Coaching) skills can be understood as comprising the application of generic interpersonal and communication skills for a specific purpose.’ It's as if an effective coach takes normal skills, hones them to a very high standard, then applies them intentionally and in a focused way to enable change with-for a client. A challenge lays in how to do this well, with wisdom and discernment, given that there are so many dynamically-complex factors in a client relationship and context that can fundamentally influence what the client will experience as beneficial. ‘The implementation of a skill in a real-life situation requires a capacity to improvise in response to what is happening in the moment.’ This is where on-going critical reflection and development is so important, perhaps with a supervisor or mentor or in an action learning set. ‘By creating opportunities for revisiting deeply ingrained ways of relating to others, the process of developing (coaching) skills can be both emotionally challenging and life-enhancing…(including) a capacity to maintain skilful and responsive contact with clients in situations of emotional pressure, such as the client becoming demanding, angry with the (coach) or withdrawn.’ I agree. So – how do you stay sharp? |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed