|

‘Good endings make sense, evoke emotions like contentment, anger, sadness, or curiosity, shift the person’s perspective or open her mind to new ideas. Good endings bring the person to some kind of destination.’ (Alex J Coyne) Lilin Lim, my sister-in-law, reads the back page of a novel first to decide whether it looks like the story is worth reading. There’s something about a good ending that can make whatever went before it feel worthwhile – the time, effort or, at times, struggle to get there. Think back to your own life and work peak experiences: e.g. birth of a child, achievement of a desired promotion or qualification, overcoming of a disability or fulfilment of a dream that, perhaps, felt hard at the time yet worked out well in the end. Conversely, think back to seminars, workshops or meetings you have taken part in that didn’t result in anything remotely meaningful to justify the investment. Academic Peter Cotterell commented satirically that, similarly, many lectures and articles can feel like, ‘a plane in the sky that takes off well yet finds itself circling in the clouds and can’t find a way to land.’ Stephen Covey said, ‘Begin with the end in mind’, a perspective that resonates well with the biblical idea of an end-revelation to draw us forward. This same principle applies in coaching and action learning. If we open a conversation with questions such as, ‘In relation to X, where do you want to be an hour from now?’ or ‘Of all the things we could spend the next hour doing together, what, for you, would make this time well spent?’, it can help ensure an explicit sense of focus and purpose from the outset – and raise into critical awareness Gary Rolfe’s movement towards an ending: the ‘Now what?’, before considering the ‘What?’ and the ‘So what?’ David Clutterbuck suggests ending this type of conversation with an invitation to the client to reflect and summarise for him- or herself, using a simple 4xI framework: ‘What are the Issues we’ve talked about; what are the Insights that you’ve had; what are the Ideas that we’ve generated; what are your Intentions now?’ It’s a consolidating technique that can enable a sense of learning and closure for the client and a transition into action. It helps to avoid the risk of a session simply...fizzling...out. Rosie Nice poses useful grounding questions: ‘Are there any other dimensions you would like to explore before moving into actions? Would it be helpful if we were to consider some questions to help you think through what actions you might take? What’s the main thing you are taking away, having had opportunity to think this through?’ Sue Murkin ends with: ‘Given what you know now, how will this impact on your work? How could you see yourself using this? What will you do now?’ How do you avoid perpetual drift or an abrupt crash landing? How do you create a good ending?

17 Comments

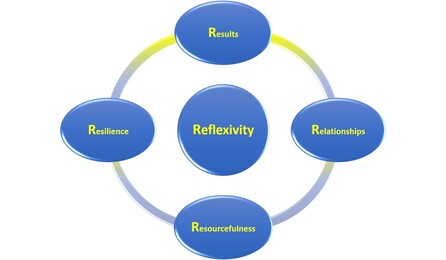

‘Don’t just do something. Stand there.’ (White Rabbit – Alice in Wonderland) It was 1 hour before the workshop was due to start and we discovered the room had been double-booked. With delegates due to arrive at any moment, the pressure and risk was to spring into action to solve this. Suddenly, I remembered the simple yet profound words of a girl in the Philippines: ‘First, pray’. So I paused, prayed, finished my cup of tea (I’m British) then walked calmly to the foyer. The manager appeared: ‘I’ve found you a fantastic alternative room at a nearby conference venue.’ Another occasion. A team meeting was due to start but the leader had been held up elsewhere. He arrived late and saw the anxious gazes of team members at the already packed-full agenda. The risk and temptation was to race through the items at breakneck speed. Instead, he paused, took a deep breath and encouraged others to do the same. Then, he turned the agenda upside down on the table. ‘What, for us, would be a great use of the time we have available?’ Sighs of relief all round. There’s a question, an idea, a principle here. Guy Rothwell calls it Space and Pace: discerning and deciding when to pause (pray) and when to leap. Pause too long and you may miss the opportunity, allow issues to escalate or frustrate others who need decisions or actions from you. Leap too soon and you may miss wiser options, fail to notice important implications or deprive others of creating better solutions. How do you handle space and pace? How do you enable others to do so too? People sometimes ask if I have a guiding framework for fields of practice that range from individual and team coaching to organisation development. To be honest, it’s difficult to pin down definitively without becoming simplistic. After all, we work with people, cultures, systems and contexts that are dynamically complex. Different people, situations and times call for different interventions. Here-and-now presence, openness, curiosity and trust are prerequisite conditions for successful outcomes. That said, I often hold 5 x Rs in mind as potential areas for attention. Each R represents a different and inter-related dimension of experience, awareness and practice that commonly influences a client’s inspiration and effectiveness. The Rs are: Results, Relationships, Resourcefulness, Resilience and Reflexivity (sometimes known as ‘critical reflective practice’ or ‘praxis’). I may explore and apply these dimensions with a client at different levels ranging from intra/inter-personal to organisational. Results focuses on who or what is most important to a client and other key stakeholders and taps into e.g. vision, values, purpose, strategy, plans and outcomes. Relationships focuses on the quality of client contact with and between key stakeholders and taps into e.g. ethics, cultures, systems, synergies and dependencies. Resourcefulness focuses on solutions, strengths and opportunities in the client/environment and taps into e.g. spirituality, talent, creativity, innovation and networks. Resilience focuses on client health, wellbeing and sustainability and taps into e.g. motivation, engagement, patterns-trends, agility and flow. Reflexivity focuses on the client’s critical self- and situational awareness, stance and actions and taps into e.g. assumptions, constructs, influences, behaviours and decisions. I place the latter at the centre of this model because, at best, it radically questions, challenges and guides all other dimensions. It lays at the heart of transformational change. What frameworks do you use and find most useful? What marks out professionals from practitioners, the best from the good? It’s a great question. One thing I would suggest is critical reflective practice (CRP). It’s a semi-structured way of learning in and through experience, often with support and challenge from peers, a coach or a non-managerial supervisor. It takes willingness and commitment, an on-going desire to learn, develop and improve. I want to suggest a four-stage CRP process (based on Kolb): experience; reflect; make sense; decide.

It will call us to pause, reflect and act; to be curious and test our assumptions, to expose our sometimes uncomfortable feelings and – for me – to pray for discernment and wisdom. Here are some sample questions. Firstly, experience: What happened? What was/am I aware of? Where was/is my attention? What was/am I feeling? What was/is the impact? Secondly, reflect: What was my intention? What beliefs or values were at play? What didn’t I notice? What assumptions was/am I making? What other options were/are available? Thirdly, make sense: What are the bigger-picture issues (e.g. politics/principles)? What wider team or organisational issues does it reveal? What is the generic issue (e.g. conflict)? What theory or research could I draw on to inform my thinking and practice? What hypotheses am I making? Finally, decide: What have I learned through this? What do I need to do the same or differently in future? How I will I prepare next time? Do any wider issues need to be addressed? What will my next step be? The third stage, ‘make sense’ distinguishes critical reflective practice from simple reflection on practice. It draws the experience and learning of others including academics and peers into the frame. It’s also the area that many professionals neglect because of time constraints – or because they are not sure how to do it. Simple ideas: journals, books, networks, conferences and LinkedIn groups. How good are you at critical reflective practice? What do you do to develop and sustain it? I met with a group of leaders last week whose roles include mentoring, supervision and pastoral support. The focus of our time together was how to learn and use a coaching approach to enhance the work they do with people and groups. In the midst of conversation, some said they would be interested to hear more about reflective practice and how to do it using coaching skills. Time was short so I hastily scribbled a reflective practice cycle on a flipchart. It draws on work by Argyris, Schon and Honey & Mumford. I explained that there are at least two ways we can think about this. Classical educationalists often start from a focus on theory, core principles etc. (and, in this group’s case, theology) and then move on to look at how to apply the theory to practice. By contrast, reflective practice often starts from observation of an experience (or experiment), then moves on to reflection on that experience, then to consider how it resonates with, challenges or informs a hypothesis or theory. This implies critical thinking and by extension, aims to guide future practice. In this sense, it shares common principles with related fields such as action research. And so how to apply a coaching approach… 1. Contracting: What are we here to do? How shall we do this? 2. Observation: What happened? What were you aware of? 3. Awareness: How did you feel? What assumptions were you making? 4. Sense-making: What surprised or confused you? How does it fit (or not) with what you know/believe? 5. Learning: ‘What have you discovered in this? 6. Action: And so..? What next? ‘I don’t have time like you for all this coaching, reading and networking stuff. In fact, if you were as busy as I am, you wouldn’t either.’ It’s a common refrain from leaders and managers who feel so time and work pressured that they can’t find space to pause, reflect or think. The more optimistic will say, ‘When things settle down…when we just get through this change…then I’ll do it.’ And yet, somehow, things never do settle down…and change follows change. And they never do do it.

Steve was a senior leader in an international organisation. We sat with a rare coffee and he looked drained, exhausted. ‘I can’t keep this up. I’m working long hours and things still stack up. What am I supposed to do?’ The idea he held in mind what that if he just worked harder, worked longer, he would be able to reduce, control and make progress with his work, finish it. It’s an understandable belief, a belief that strains to provide a glimmer of hope, yet so often it’s basically - wrong. Illusion. I shared an image of a huge pile of sand, Steve digging away with a teaspoon at the bottom. No matter how committed he was, no matter how hard or fast he dug, no matter how skilfully he did it, sand would continue to tip in. There is no end, especially as the world is adding sand to the top of the pile faster than he can ever remove it. Yet there is a solution. It means stepping back, praying, reviewing, reflecting, reprioritising, renegotiating – in a nutshell, making choices rather than just doing. The paradox, of course, lays in making time to do this. Yet, as one of my leader colleagues commented today, ‘A pit stop doesn’t mean slowing down’. It’s about creating optimal space to breathe, recover, invite challenge, test assumptions, find perspective, explore ideas; in other words, to safeguard just enough time for the proverbial dust to settle to see clearly again. This is where things like coaching, reading and networking can prove so valuable. What do you do to take your pit stops? How would you describe your coaching style? What questions would you bring to a client situation?

In my experience, it depends on a whole range of factors including the client, the relationship, the situation and what beliefs and expertise I, as coach, may hold. It also depends on what frame of reference or approach I and the client believe could be most beneficial. Some coaches are committed to a specific theory, philosophy or approach. Others are more fluid or eclectic. Take, for instance, a leader in a Christian organisation struggling with issues in her team. The coach could help the leader explore and address the situation drawing on any number of perspectives or methods. Although not mutually exclusive, each has its own focus and emphasis. The content and boundaries will reflect what the client and coach believe may be significant: Appreciative/solutions-focused: e.g. ‘What would an ideal team look and feel like for you?’, ‘When has this team been at its best?’, ‘What made the greatest positive difference at the time?’, ‘What opportunity does this situation represent?’, ‘On a scale of 1-10, how well is this team meeting your and other team members’ expectations?’, ‘What would it take to move it up a notch?’ Psychodynamic/cognitive-behavioural: e.g. ‘What picture comes to mind when you imagine the team?’, ‘What might a detached observer notice about the team?’, ‘How does this struggle feel for you?’, ‘When have you felt like that in the past?’, ‘What do you do when you feel that way?’, ‘What could your own behaviour be evoking in the team?’, ‘What could you do differently?’ Gestalt/systemic: e.g. ‘What is holding your attention in this situation?’ ‘What are you not noticing?’, ‘What are you inferring from people’s behaviour in the team?’, ‘What underlying needs are team members trying to fulfil by behaving this way?’, ‘What is this team situation telling you about wider issues in the organization?’, ‘What resources could you draw on to support you?’ Spiritual/existential: e.g. ‘How is this situation affecting your sense of calling as a leader?’, ‘What has God taught you in the past that could help you deal with this situation?’, ‘What resonances do you see between your leadership struggle and that experienced by people in the Bible?’, ‘What ways of dealing with this would feel most congruent with your beliefs and values?’ An important principle I’ve learned is to explore options and to contract with the client. ‘These are some of the ways in which we could approach this issue. What might work best for you?’ This enables the client to retain appropriate choice and control whilst, at the same time, introduces possibilities, opportunities and potential new experiences that could prove transformational. What are your favourite coaching questions? I often use 3 that I’ve found can create a remarkable shift in awareness, insight and practice, especially in team coaching. I’ve applied them using variations in language and adapted them to different client issues, opportunities and challenges. They draw on principles from psychodynamic, Gestalt and solutions-focused coaching and are particularly helpful when a client or team feels stuck, unable to find a way forward.

* ‘What’s your contribution to what you are experiencing?’ * ‘What do you need, to contribute your best?’ * ‘What would it take..?’ Client: ‘These meetings feel so boring! I always leave feeling drained rather than energised.’ Coach: ‘What’s your contribution to what you are experiencing?’ Client: ‘Excuse me?’ Coach: ‘What do you do when you feel bored?’ Client: ‘I drift away, look out of the window.’ Coach: ‘What might be the impact on the wider group when you drift away?’ Client: ‘I guess others may disengage too.’ Coach: ‘How does the meeting feel when people disengage?’ Client: 'Hmmm…boring!’ Coach: ‘What do you need to contribute your best?’ Client: ‘It would help certainly if we could negotiate and agree the agenda beforehand, rather than focus on things that feel irrelevant.’ Coach: ‘So you want to ensure the agenda feels relevant to you. What else?’ Client: ‘If we could meet off site and break for coffee from time to time, that would feel more energising.’ Coach: ‘So venue and breaks make a difference too. Anything else?’ Client: ‘No, that’s it.’ Client: ‘I don’t think I can influence where and how these meetings are held.’ Coach: ‘It sounds like you feel quite powerless. How would you rate your level of influence on a scale of 1-10?’ Client: ‘Around 3’. Coach: ‘What would it take to move it up to a 6 or 7?’ Client: ‘I guess if I showed more support in the meetings, the leader may be more open to my suggestions.’ Coach: ‘What else would it take?’ Client: ‘I could work on building my relationship with the leader outside of meetings too.’ These type of questions can help a client grow in awareness of the interplay between intrapersonal, interpersonal and group dynamics, his or her impact within a wider system, what he or she needs to perform well and how to influence the system itself. They can also shift a person or team from mental, emotional and physical passivity to active, optimistic engagement. What are your favourite coaching questions? How have you used them and what happened as a result? I took my mountain bike for repairs last week after pretty much wrecking it off road. In the same week, I was invited to lead a session on ‘use of self’ in coaching. I was struck by the contrast in what makes a cycle mechanic effective and what makes the difference in coaching. The bike technician brings knowledge and skill and mechanical tools. When I act as coach I bring knowledge and skills too - but the principal tool is my self.

Who and how I am can have a profound impact on the client. This is because the relationship between the coach and client is a dynamically complex system. My values, mood, intuition, how I behave in the moment…can all influence the relationship and the other person. It works the other way too. I meet the client as a fellow human being and we affect each other. Noticing and working with with these effects and dynamics can be revealing and developmental. One way of thinking about a coaching relationship is as a process with four phases: encounter, awareness, hypothesis and intervention. These phases aren’t completely separate in practice and don’t necessarily take place in linear order. However, it can provide a simple and useful conceptual model to work from. I’ll explain each of the four phases below, along with key questions they aim to address, and offer some sample phrases. At the encounter phase, the coach and client meet and the key question is, ‘What is the quality of contact between us?’ The coach will focus on being mentally and emotionally present to the client…really being there. He or she will pay particular attention to empathy and rapport, listening and hearing the client and, possibly, mirroring the client’s posture, gestures and language. The coach will also engage in contracting, e.g. ‘What would you like us to focus on?’, ‘What would a great outcome look and feel like for you?’, ‘How would you like us to do this?’ (If you saw the BBC Horizon documentary on placebos last week, the notion of how a coach’s behaviour can impact on the client’s development or well-being will feel familiar. In the TV programme, a doctor prescribed the same ‘medication’ to two groups of patients experiencing the same physical condition. The group he behaved towards with warmth and kindness had a higher recovery rate than the group he treated with clinical detachment). At the awareness phase, the coach pays attention to observing what he or she is experiencing whilst encountering the client. The key question is, ‘What am I noticing?’ The coach will pay special attention to e.g. what he or she sees or hears, what he or she is thinking, what pictures come to mind, what he or she is feeling. The coach may then reflect it back as a simple observation, e.g. ‘I noticed the smile on your face and how animated you looked as you described it.’ ‘As you were speaking, I had an image of carrying a heavy weight…is that how it feels for you?’ ‘I can’t feel anything...do you (or others) know how you are feeling?’ (Some schools, e.g. Gestalt or person-centred, view this type of reflecting or mirroring as one of the most important coaching interventions. It can raise awareness in the client and precipitate action or change without the coach or client needing to engage in analysis or sense-making. There are resonances in solutions-focused coaching too where practitioners comment that a person doesn’t need to understand the cause of a problem to resolve it). At the hypothesis stage, the coach seeks to understand or make sense of what is happening. The key question is, ‘What could it mean?’ The coach will reflect on his or her own experience, the client’s experience and the dynamic between them. The coach will try to discern and distinguish between his or her own ‘stuff’ and that of the client, or what may be emerging as insight into the client’s wider system (e.g. family, team or organisation). The coach may pose tentative reflections, e.g. ‘I wonder if…’, ‘This pattern could indicate…’, ‘I am feeling confused because the situation itself is confusing.’ (Some schools, e.g. psychodynamic or transactional analysis, view this type of analysis or sense-making as one of the most important coaching interventions. According to these approaches, the coach brings expert value to the relationship by offering an explanation or interpretation of what’s going on in such a way that enables the client to better understand his or he own self or situation and, thereby, ways to deal with it). At the intervention phase, the coach will decide how to act in order to help the client move forward. Although the other three phases represent interventions in their own right, this phase is about taking deliberate actions that aim to make a significant shift in e.g. the client’s insight, perspective, motivation, decisions or behaviour. The interventions could take a number of forms, e.g. silence, reflecting back, summarising, role playing or experimentation. Throughout this four-phase process, the coach may use ‘self’ in a number of different ways. In the first phase, the coach tunes empathetically into the client’s hopes and concerns, establishing relationship. In the second, the coach observes the client and notices how interacting with the client impacts on him or herself. The coach may reflect this back to the client as an intervention, or hold it as a basis for his or her own hypothesising and sense-making. In the third, the client uses learned knowledge and expertise to create understanding. In the fourth, the coach presents silence, questions or comments that precipitate movement. In schools such as Gestalt, the coach may use him or herself physically, e.g. by mirroring the client’s physical posture or movement or acting out scenarios with the client to see what emerges. In all areas of coaching practice, the self is a gift to be used well and developed continually. What’s your theory of change? What issues are you trying to address? What creates and sustains those issues? What kind of interventions and when are most likely to prove successful? What would success look and feel like, and for whom? What is your overall goal? These are some of the questions we looked at on a Theory of Change workshop I took part in yesterday. Theories of change are becoming increasingly commonplace in the third sector, paralleling e.g. strategy maps in other sectors. There are a number of reasons for this. Charities and NGOs are under increasing scrutiny from supporters and funders to demonstrate how their resources are being used to achieve optimal impact. This has created a whole industry in impact evaluation.

The third sector is maturing too. No longer driven into action by empathy or altruistic instinct alone, organisations in this sector have more experience, more evidence of what works and what doesn’t and more analysis and understanding of why. The issues have turned out to be more complex than some had originally imagined, making significant and sustained progress challenging. Against this backdrop, a theory of change can prove valuable. It aims to clarify goals and outcomes and to work back to activities and other factors that will enable the outcomes to be achieved. In articulating these things clearly and succinctly (often in simple graphic flowchart form), underlying assumptions and causal links can be surfaced, explained and tested. At heart, a theory of change answers questions such as ‘What are we trying to achieve?’, ‘What is necessary for the goal to be achieved?’ and ‘What’s the rationale behind our intervention strategy?’ In doing so, it makes the organisation’s focus, operations and use of resources transparent, accountable and more open to challenge and improvement as new research and evidence emerges. I find myself particularly drawn to the critical-reflective aspects. For instance, one NGO I worked with conducted a fundamental strategy review starting with these same principles, asking questions such as, ‘Why are people poor?, ‘What causes and sustains poverty?’, ‘What interventions make the greatest difference?’, ‘What is our optimal contribution?’ One of the interesting challenges for a third sector organisation is whose voice is represented in framing and answering such questions, e.g. donors, beneficiaries, trustees, staff, volunteers. A charitable organisation I work with currently conducted a strategy review recently, inviting feedback from beneficiaries using surveys, focus groups etc. to find out what they struggle with and aspire to and what role they would want to see the organisation playing in helping them address or achieve these issues. The needs and aspirations that surfaced have been summarised as ‘I’ rather than ‘we’ or ‘they’ statements in clear and colloquial language, keeping the focus on what each individual as beneficiary wants to experience as a result of the organisation’s actions. This is a sharp contrast with some experiences I’ve had in the past. In one instance, a third sector organisation I worked with set up a drop-in project providing advice and support for long-term unemployed people. The Local Authority provided funding using ‘number of people using the service’ as its key success criterion. Paradoxically, the more successful the service was in enabling local people to find employment, thereby reducing the number of people who needed to access the service, the more the service was deemed statistically by the Local Authority to be failing. A theory of change can help surface such outcomes and assumptions at an early stage, enabling more constructive dialogue and agreement between agencies and stakeholders. I believe the potential for theory of change extends beyond third sector organisations aiming to articulate their vision, strategy, plans and reasons behind them. I’ve used similar methodologies to explore and articulate an organisation development strategy within a third sector organisation. We started by exploring a number of questions with diverse stakeholders and groups such as, ‘What kind of organisation are we trying to develop?’, ‘Where are we now?’, ‘Why are things as they are?’, ‘What drives or sustains how things are?’, ‘What matters most to people here?’, ‘Who or what influences change?’, ‘What would it take to achieve the changes?’ This enabled us to create a map showing goals, activities, assumptions and causal relationships. The same principles can be applied at team and individual levels too, e.g. for leadership, coaching, mentoring, training and counselling purposes. It enables dialogue between different parties and keeps rationale and assumptions explicit. If assumptions are clear to all parties, they can be challenged and revised in light of different preferences, perspectives, realities and evidence. I’ve used adaptations of this approach with people and organisations where Christian beliefs have been held as important and integral, developing the model as a theology of change. A theology of change may surface and articulate e.g. God’s purpose, values, presence and activity in the world, the role of the Spirit and Christians, discerning a sense of ‘calling’. In my experience, the language and methods of applying theory or change need to be adapted for different purposes and audiences. It represents a logical-rational paradigm that is likely to work well for some people and cultures but not so well for others. Using Honey & Mumford’s learning styles as one possible frame of reference, theory of change (as the name implies) may appeal most to people, teams or cultures with a theorist orientation. Reflectors may be attracted most by its emphasis on surfacing underlying assumptions, activists by the evidential dimensions and pragmatists by its focus on outcomes. Perhaps the key lies in using the principles it embodies flexibly and sensitively in the context of real human dialogue and relationship. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed