|

‘Learning is a treasure that will follow its owner everywhere.’ (Chinese proverb) Action Learning facilitator training with different participant groups always surfaces fresh and fascinating insights, emphases and challenges. This week’s ALA training programme was with a group of health professionals in diverse roles and fields of practice ranging from nursing, occupational therapy and podiatry to mental health, speech and language and education. I was inspired by their enthusiasm, personal ethics and genuine commitment to culture change. As we worked through Action Learning principles and techniques and how to enable groups to do it well, we explored 5 shift areas to facilitate a transition: from diagnosis to elicitation; from issue to person; from there-and-then to here-and-now; from first questions to follow-up questions; from reflection to agency. I’ll say a little about each of these dimensions with some practical examples below. The goal in each is to enhance participants’ learning and impact. From diagnosis to elicitation is a shift in who owns the issue from, say, ‘Tell me more about X so I can help you?’ to e.g. ‘What questions is X raising for you?’ From issue to person is a shift in focus from, say, ‘What’s the situation?’ to e.g. ‘What challenge is this situation posing for you?’ From there-and-then to here-and-now is a shift in temporal orientation from, say, ‘What have you tried?’ to e.g. ‘Given what you have tried, what stands out as the critical issue now?’ From first questions to follow-up questions is a shift in depth to move below and beyond, say, ‘How important is this to you?’ to e.g. ‘Given how important this is to you, what are you willing to risk?’ From reflection to agency represents a shift in traction from, say, ‘What sense are you making of this?’ to e.g. ‘What actions will you take to address this?’ A skill of the facilitator is to build the capacity of an Action Learning set to navigate these shifts in service of a presenter.

8 Comments

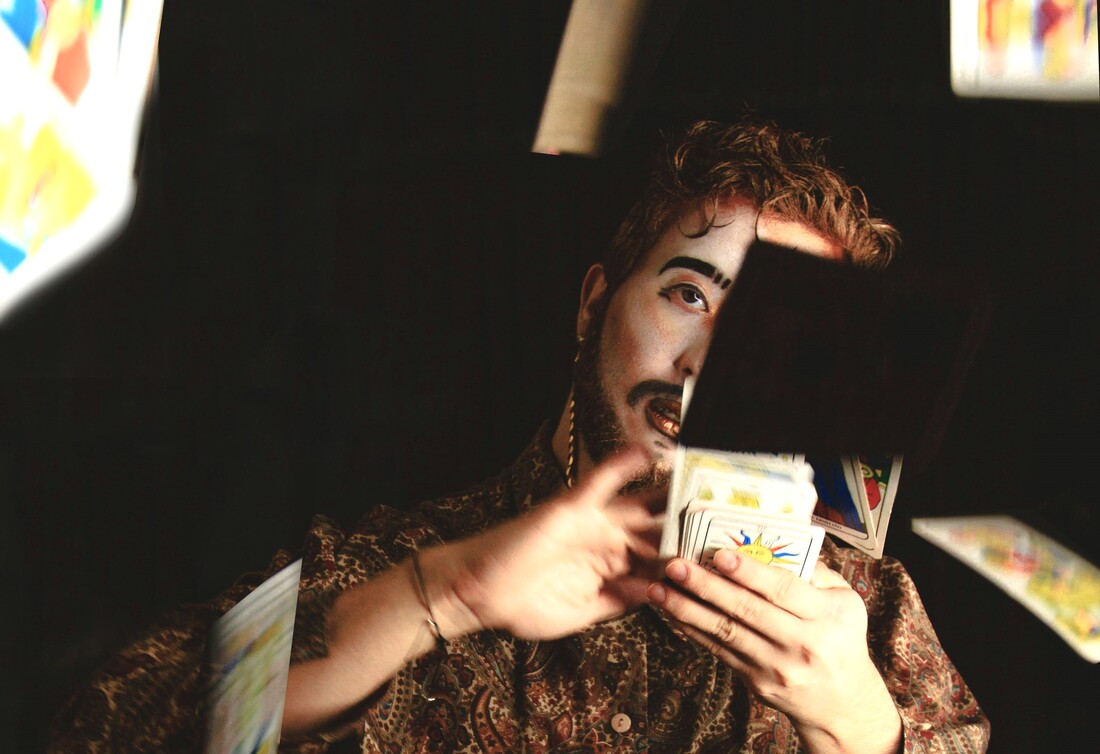

‘Intuition is like reading a word without having to spell it out.’ (Agatha Christie) I had the privilege of training an inspiring, cross-cultural group of participants in South Africa, Rwanda and the UK this week who work in different roles in the same international non-governmental organisation (INGO). This online Action Learning Associates programme was designed to enable them to facilitate Action Learning sets (that is, groups) confidently and effectively. (If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of Action Learning, it’s a semi-structured, small-group, peer-coaching process that’s used widely in leadership and management development programmes and as part of wider organisation development (OD) initiatives). One of the areas we touched on during the training event is the value of drawing on intuition when facilitating groups. We could consider the facilitator’s role simply in terms of a series of tasks, e.g. introducing a meeting; leading a check-in; contracting ground-rules; guiding the group through the sequential steps of an Action Learning process; facilitating a review at the end. These are important elements that we learn to handle skilfully. At a deeper level, however, we can learn to tune into our intuition. This will help us to discern, for instance, unspoken issues; underlying group dynamics; or when a person-group is stuck or ready to move on. Intuition can feel mysterious, a sense of ‘knowing’ that we may experience bodily or as a feeling rather than as a rational concept in our mind. One of most mysterious experiences I had was when training a group of church and community leaders in Action Learning facilitation. When I first encountered one of the participants, the word ‘Ruth’ kept coming to mind. I mentioned this to him very tentatively and he looked astonished. Apparently, he was about to complete a PhD study on the book of Ruth in the Bible. I had no idea. For me, spiritual discernment sits close to intuition. I always pray deeply before coaching or facilitating a set. How do you draw on intuition in your own life and practice? I’d love to hear from you! ‘Curiosity killed the cat, but for a while I was the suspect.’ (Steven Wright) Action Learning facilitators sometimes feel anxious if there are prolonged periods of silence in a group, or if an individual is particularly quiet. They may assume, for instance, that the person is uninterested to engage with the group or the process. I had that experience once (online) where a participant sat throughout a round wearing headphones, nodding and swinging in his chair as if to music. When I asked if he had any questions, he clearly had no idea what the presenter had been talking about. I addressed this with him directly after the round, checked if there was anything he would need to be and feel more engaged, then agreed that he would leave the set. That said, there are a wide range of potential factors that may influence if and how a person engages in a set meeting and, at times, different reasons for the same participant during different rounds. I will list some of them here as possibilities: if a person has been sent to a set, rather than has chosen freely to join it; if there is formal or cultural hierarchy within the group; if there has been insufficient attention paid to agreeing ground-rules for psychological safety; if building relational understanding and trust has been neglected; if a person doesn’t like someone else in the group, or fears negative evaluation by others in the set; if a person lacks confidence. There are other possibilities too: if a person has an introverted preference and processes thoughts and feelings internally; if a person has a reflective personality and needs more time to think; if a person doesn’t feel competent with the language or jargon being used; if the person can’t think of a presenting issue or a question; if last time the person spoke up in a group meeting, it was a difficult experience or had negative consequences; if a person is preoccupied with issues or pressures outside of the meeting; if a person is distracted mentally or impacted emotionally by something that happened before the meeting, or is due to happen after it. So, what to do if a person is completely silent in a set? Here are some ideas, to be handled with sensitivity and, if appropriate, outside of the meeting: take a compassionate stance – there may be all kinds of reasons for the silence of which you are unaware; avoid making judgements – silence does not necessarily indicate disengagement; be curious – ask the person tentatively, without pressure, if any issues or questions are emerging for them; avoid making assumptions – ask the person what the silence means for them and if there’s anything they need; have an offline conversation with the person – if their silence persists for more than one meeting. ‘Stop imagining. Experience the real. Taste and see.’ (Claudio Naranjo) Early predictions that electronic reading technologies would supersede the need for physical paper books proved unfounded. There’s something about holding a book, turning the pages, feeling the paper and smelling the ink that feels tangibly different to viewing text on screen. It’s something about reading as an experiential phenomenon that goes further and deeper than passively absorbing visual input. We’re physical beings and physical touch, movement and feeling still matter to us. I’ve noticed something similar in coaching conversations, stimulated by studies and experiments in the field of Gestalt. Against that backdrop, using physical props that invite physical interaction with those props can create shifts at psychological levels too. I have 4 different packs of cards available*, alongside other resources, and I notice that holding, sifting through and laying out cards can sometimes feel more engaging and stimulating for a client than thinking and talking alone. Each pack has a different purpose and focus. All involve inviting a client to flick through the cards to see which images, words, phrases or questions resonate for them here-and-now. It’s as if, at times, we’re able to recognise someone or something that matters to us, is meaningful for us, by touching and viewing it ‘out there’, rather than ‘in here’. The cards also enable a client, team or group to move or configure them in experimental combinations to see what insights, themes or ideas emerge. (*The Real Deal; Empowering Questions; Gallery of Emotions; Coaching Cards for Managers) ‘The currency of real networking is not greed, but generosity.’ (Keith Ferrazzi) One of the skills in Action Learning is to distinguish between a presenter who is wrestling with a question from one who has become completely stuck. In the former case, it’s often most useful simply to sit with the presenter in silence while the question does its work. In the latter, the facilitator may offer the presenter an option of ‘peer-consultancy’, if it might help break the mental deadlock. In order to do this well, however, and to ensure that ownership and agency remain with the presenter, the facilitator can follow a specific sequence of interventions and process steps:

A few words of caution. First, beware of introducing the peer-consultancy approach without checking in with the presenter first. If the presenter is deep in thought, such a shift in approach may feel premature of patronising, as if inferring that they’re unable to work out a solution for themselves. Second, beware of any formal or informal (e.g. age, gender, race) hierarchical dynamics in a group. Presenters may feel that they ought to respond to all insights out of respect for those who shared them, or obliged to agree with ideas proposed by someone they regard as an authority figure. ‘The question is to provoke fresh thought, not to elicit an answer.’ (Stephen Guy) I thought that was a great way of framing it. At an Action Learning Facilitators’ Training event with the NHS this week, we were looking at open coaching-type questions in the exploration phase of an Action Learning round and how they differ from, say, simple questions for clarification. A great question for exploration often stops a presenter in their thinking tracks. We may notice them fall silent; gaze upwards as if on search mode; get stuck for words; speak tentatively or more…slowly. That’s very different to a presenter who answers quickly, fluently or easily – as if telling us something they already know or have already thought through for themselves. In a different Action Learning set recently, one presenter did just that. They were speaking as an expert, not as a learner, so I invited them to count to 10 silently before responding to any question posed – and invited the rest of the group to count to 10 silently too, after the presenter had spoken, before offering a next question. The idea here was to allow the questions to sink deep. Thomas Aquinas, a philosopher and theologian, commented (my paraphrase) that a great question sets us off on a journey of discovery. Brian Watts observed, similarly, that the word question itself has the word quest embedded in it. Sonja Antell invites a presenter simply – but not always easily – to ‘sit with the question’, to reflect in silence and allow the question to do its work. It’s often the place where transformation occurs. ‘Action Learning aims to shake you out of the cage of your current thinking.’ (Pedler & Boutall) Action Learning: a method by which someone receives stretching, coaching-type questions from a small group of peers. The aim is to resolve a pressing challenge, a real-life/work issue that has left the person perplexed or stuck. The idea is to leave with actions, practical steps that will help to move things forward. Yet what gets a person stuck in the first place? If it’s a complex challenge, such as that of navigating the intricacies of diverse human relationships, we may become inadvertently caged by our own assumptions. Gareth Morgan commented that ‘people have a knack for getting trapped in webs of their own creation.’ If we don’t know what assumptions we’re making, everything may seem self-evident to us. This is where Action Learning and coaching really can help. If we can engender a spirit of curiosity within ourselves and invite challenging questions from different others, we may discover a door emerging in our previously-unseen cage, experience the agency to push it wide open and step outside to embrace fresh possibilities. It could just change...everything. ‘Open-ended questions can help clients reflect and generate knowledge of which they may have previously been unaware.’ (Jeremy Sutton) You may have noticed when you order or buy something that, before asking you for payment, the salesperson may ask, ‘Anything else?’ It’s a simple prompt that, when posed, may cause you to remember something, or to make a choice vis a vis something over which you had been wavering. This same approach can be useful in coaching. A coach could ask during the contracting stage: ‘Is there anything else we should be talking about?’ It can sometimes reveal a very significant issue that, until invited, feels unclear to the client, lays out of conscious awareness or has not yet been aired. In action learning, similarly when a facilitator invites a presenter to say something more about the issue they would like to think through, insights that come to mind or actions they plan to take, they can ask, ‘Anything else?’ A presenter, when prompted, will often respond with: ‘Oh yes, and…X’ So, now for a brief moment of reflection. What ideas come to mind for you now as you read this blog? Jot down those that surface immediately… then pause for a moment before moving on to something else in your busy schedule. Ask yourself: ‘Anything else?’ and see what may emerge. ‘Behind every problem, there is a question trying to ask itself. Behind every question, there is an answer trying to reveal itself.’ (Michael Beckwith) Second-guessing. It creates all sorts of risks. ‘What time does Paul’s meeting finish?’ Is that a simple request for information, or is there a question behind the question? ‘I’d like to meet with Paul this afternoon. What time will he be free?’ That’s better. ‘I need you to present an urgent strategy update to the Board.’ Again, is that a simple instruction, or is there an issue that lays behind it? ‘I’d like to demonstrate to the Board next week that our investments are achieving the desired results.’ Better. A problem with a question that fails to reveal the question, the issue, that lays behind the question is that it leaves the other party to fill in the gaps. In doing so, they are likely to draw on their own assumptions – which could be very different to your own – or sometimes their anxieties. ‘Is he complaining that Paul’s meeting is over-running?’ ‘Is she inferring there’s a problem with my work on strategy delivery that I hadn’t been aware of?’ Simply stating our intention can make all the difference. 'Listen with curiosity. Speak with honesty. Act with integrity.' (Roy T. Bennett) Action Learning facilitators sometimes feel concerned about what might happen in a set (a small group of peer-coaches) and how they might handle it if it does. When we discuss these kind of troubleshooting scenarios in training, I often notice that facilitators feel a sense of personal responsibility to manage anything and everything that might happen. Apart from placing a lot of pressure on the facilitator which could, in the moment, inhibit psychologically their ability to handle any challenges that may arise anyway, it also misses the self-resourcing potential of a group. The key often lays in shifting the facilitator’s stance from control to curiosity. This doesn’t mean abandoning the governance role of the facilitator altogether, for example to ensure that agreed ground rules and process are followed appropriately. It does, however, mean approaching any challenges that emerge in an invitational tone. For instance, if the group is very quiet, or conversely very talkative, and this leaves the presenter perhaps with little stimulus or space for reflection, the facilitator can offer this as a judgement-free observation, like holding up a mirror to the set. ‘I’m noticing the group seems very quiet. I’m wondering what that might mean?’ Or, ‘I’m wondering what we might need?’ It could be that participants don’t know and trust each other well enough yet. It could be that they don’t believe they have understood the presenter’s challenge and feel nervous to admit it. It could be that they feel insecure about posing a ‘wrong’ question in front of peers. It could be they have an introverted preference and simply need time to reflect before framing a question. A spirit of curiosity can open things up, release stuck-ness and move things forward. |

Nick WrightI'm a psychological coach, trainer and OD consultant. Curious to discover how can I help you? Get in touch! Like what you read? Simply enter your email address below to receive regular blog updates!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed